Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

What do you do when you make a fact error online?

The answer is simple: Fix it and flag the correction, either via a strikethrough or a traditional correction.

No journalist likes a correction, of course. They’re an admission of failure. Many of them are downright embarrassing.

Writing through stories has gotten much easier to do in the digital era, of course, and unflagged changes can be unsettling, to say the least, as Arthur Brisbane documented in some detail for and about The New York Times. In the press age, newspapers often got away with avoiding them, either by ignoring complainants altogether or by cleaning up copy between editions, with most readers none the wiser.

But the very malleability of digital technology has led to shifting standards as to when copy can be simply tweaked, updated, full-on corrected, or subjected to some other variation on the theme. This can and should benefit readers but all too often it doesn’t.

On Wednesday, for instance, Columbia’s Emily Bell, who’s on CJR’s three-year-old board of overseers, wrote a Guardian column pointing out the stark gender disparities at the new journalist startups.

This is a very real, very important issue, obviously, but one thing that stood out to me was a line on Nate Silver having hired many more men than women for his new site with ESPN:

Last count: 19 men and six women on the editorial staff. By the sophisticated math of this pundit – and Silver hates pundits – that is just under 30%

That contained a rather obvious and ironic math error I couldn’t resist pointing out on Twitter.

But then the Lord of Numbers himself descended to swat me down, faulting me for not being able to do basic math:

@ryanchittum: 6 into 19 is 31.6% (>30%). Not that there's a need for journalists to have better math skills or anything.

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) March 12, 2014

Ouch!

Had I completely misread the line? I went back to Bell’s piece and sure enough, it read, “Last count: six women on the 19-person editorial staff. By the sophisticated math of this pundit – and Silver hates pundits – that is just under over 30%.”

@NateSilver538 my bad. I read it as 6 women and 19 men

— Ryan Chittum (@ryanchittum) March 12, 2014

But I hadn’t been wrong at all, as I learned thanks to another reader who’d seen the original. The Guardian had just rewritten the incorrect passage without striking it through or otherwise noting it. And by doing so, Nate Silver incorrectly told his 670,000 Twitter followers (ADDING: Or some of them, anyway. It was an @ reply). that I was part of a “how many journalists does it take to calculate a percentage?” joke.

To her credit, Bell told me she’d have The Guardian make the change public, though, as I write this, it hasn’t happened.

Rewriting without correcting is hardly a one-off Guardian thing and much of the time it presumably doesn’t result in cascading bad information like it did here.

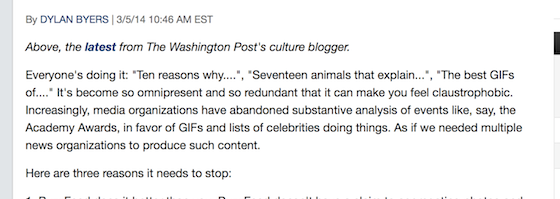

Politico‘s Dylan Byers made a mistake last week when he wrote this, “Above, the latest from the The Washington Post’s ‘social media reporter'”, (scare quotes are his, by the way), which resulted in this:

@DylanByers @politico You got my title wrong. ;)

— Caitlin Dewey (@caitlindewey) March 5, 2014

Byers’s post now looks like this:

There’s no notification that the text was changed to correct a fact error.

Last summer, a New York Daily News reporter sneered at iMediaEthics for asking why the New York Daily News fixed a blatant fact error without noting its mistake.

Obviously, people write through stories as news develops. It’s fine to clean up copy errors or clarify something. But when you correct a fact, you just have to point out the original error. It’s unfair otherwise.

There are grayer areas too, like when The New York Times led its obituary of rocket scientist Yvonne Brill with the fact that “she made a mean beef stroganoff”, caught quite a bit of heat for that, and subsequently disappeared the offending text, as you can see via NewsDiffs. The Times at least should have tagged a note to the end of the piece explaining the Removal of the Stroganoff.

The optimal solution for the rewrite problem would be to have a way to make changes to copy transparent to readers who want to see how a story has developed over time—or who want to make sure they’re not crazy when they can’t find something they could swear they read earlier. That’s not going to happen, so we’ll have to rely on a site like NewsDiffs, which catalogs changes in news stories at the NYT, Politico, the Post, CNN, and the BBC.

Unfortunately, it can’t cover them all.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.