There are times when I get in a YouTube mood and I lose a day, maybe two, watching video clips. Often this happens when I can’t sleep. I turn my phone sideways and wander the vast metropolis of the uploaded, in search of novelty, history, laughter, minor disasters, kindness, instant karma, disarming animal faces, and reviews of fast lenses by Kaiman Wong. YouTube has shown me garrulous unboxing videos, baby elephants saved from drowning by their mothers and aunts, outtakes from old newsreels, and title sequences of seventies sitcoms. It has shown me John and Yoko on Dick Cavett, Mary McCarthy on Jack Paar, Arundhati Roy interviewed in a garden, and the trailer for the movie version of John Cheever’s “The Swimmer.” This one mega-monster-website has taught me how to refill power-steering fluid in a ten-year-old Honda Civic, how to program a Honeywell thermostat, and how to de-pixelate jaggy images in Photoshop. It’s brought me evidence of the infinitude of unsung, uncredited human effort and experience. I’ve also watched the plucky Subway Rat haul a slice of pizza down stairs, and I’ve felt a kinship with him, or her.

YouTube, this endless, crowd-curated theater of ourselves, serves up the raw, the cooked, the failing, the heartrending, the shocking, the helpful, and the WTF? any time you want it. So a few months ago, when the Columbia Journalism Review asked me to watch YouTube videos for a little while, as an experiment, to see what news of the world was served up by its freshly tuned algorithm, I of course said yes.

And then I made a mistake. Using YouTube’s own search bar, I looked up some terms that I thought I should know more about before beginning: “deep state,” for instance. Soon I was blitzed and blistered by a series of bizarre insanities that I vaguely knew existed within cultish communities of confused truthers, but which I had never been exposed to firsthand. I was offered a gigantic YouTube playlist called “Political”—494 videos gathered by someone named kitsaplady, who is apparently from Kitsap, Washington—about an elite global network of pedophiles, Satan worshippers, and 9/11 plotters. “What we’re going to be talking about today is pure evil,” says an interviewer, speaking to a man in a blue button-down shirt. The button-down-shirt man contends that three women—Hillary Clinton, Janet Reno, and “my sister Marcy”—control the biggest pedophilia network in the world. “God asked me to expose evil,” he says.

I went on to watch more videos in the playlist, many of them about Cathy O’Brien, who in the nineties cowrote a book called Trance about her years as a CIA-programmed sex slave for world leaders; she claimed that she’d been abused by George H.W. Bush, Gerald Ford, Senator Robert Byrd, Pierre Trudeau, and Hillary Clinton. (Not by Bill Clinton, though; according to O’Brien, Bill tended more toward the homosexual end of the spectrum.) An excerpt from one of O’Brien’s talks was posted to YouTube on October 15, 2016, weeks away from the presidential election. It was entitled “Cathy O’Brien: Hillary Clinton Raped Me.”

“I’m going to do something I’ve never done before,” says Glenn Canady, the man who posted the Cathy O’Brien clip. “I’m going to put out a cash reward, five hundred dollars, to whoever contacts Alex Jones.” If enough people alert Jones, and he does a story on Cathy O’Brien, it will get Donald Trump elected, Canady claims. “We’ve got the sworn testimony of Cathy O’Brien on video all over YouTube—you can type in ‘Hillary Clinton Cathy O’Brien,’ ” he continues. “Find those videos.” Then he announces that he’s going to sweeten the pot. “If you’re the person who does this, who puts out Cathy O’Brien, and it gets picked up by Drudge afterwards, I’m going to give you a thousand dollars. That’s how important it is. Because, guys, what good does this money do me if we’re all dead, if Hillary Clinton gets elected? Because she’s going to come for our guns. You do not have a weapon like Cathy O’Brien and not use it. You have to use every weapon in your arsenal.”

Jones, on Infowars, his enormously popular and (self-admittedly) psychotic show, did, in fact, the very next day in October, run something about Hillary Clinton and sexual abuse. Pizzagate—the ridiculous, now exhaustively debunked story of Clinton, a child sex ring, and a pizzeria in Washington, DC—ensued a few weeks later. In the summer and fall of 2016, YouTube was clearly a platform for election-swaying mental confusion and meme manipulation.

But that was not all I found in the long playlist from kitsaplady. I watched a former CIA officer and United States Marine named Robert David Steele, now an anti-Zionist Trump booster, talk authoritatively into his camera about “adrenochrome” in June 2017. Steele says:

The Republican Party has historically been the party that is most connected to Wall Street, the Illuminati, and the Satanists that used pedophilia as well as—this is a very delicate topic. It turns out that drinking children’s blood is an anti-aging device. This is just really sick and disgusting, but it’s a fact, it’s a chemical fact. If you drink adrenalized children’s blood, which is to say you terrorize the child—not just with sodomy but with torture and other satanic ritual things—if you adrenalize the child’s blood before you kill them and drink their blood, this is a doubly effective anti-aging device. You can also harvest children’s bone marrow.

I hit the space bar, pausing the video. “Wow,” a commenter had posted. “This guy is sick and delusional. He needs medication.” No more, I thought; I can’t write about YouTube after all. In search of alternative political opinions, I’d entered a world of deranged cranks saying awful things. A YouTube that offers videos about satanic pedophilia networks is not the YouTube I knew and, in my innocence, loved. It’s all over. I’m done.

YouTube, this endless, crowd-curated theater of ourselves, serves up the raw, the cooked, the failing, the helpful, and the WTF? any time you want it.

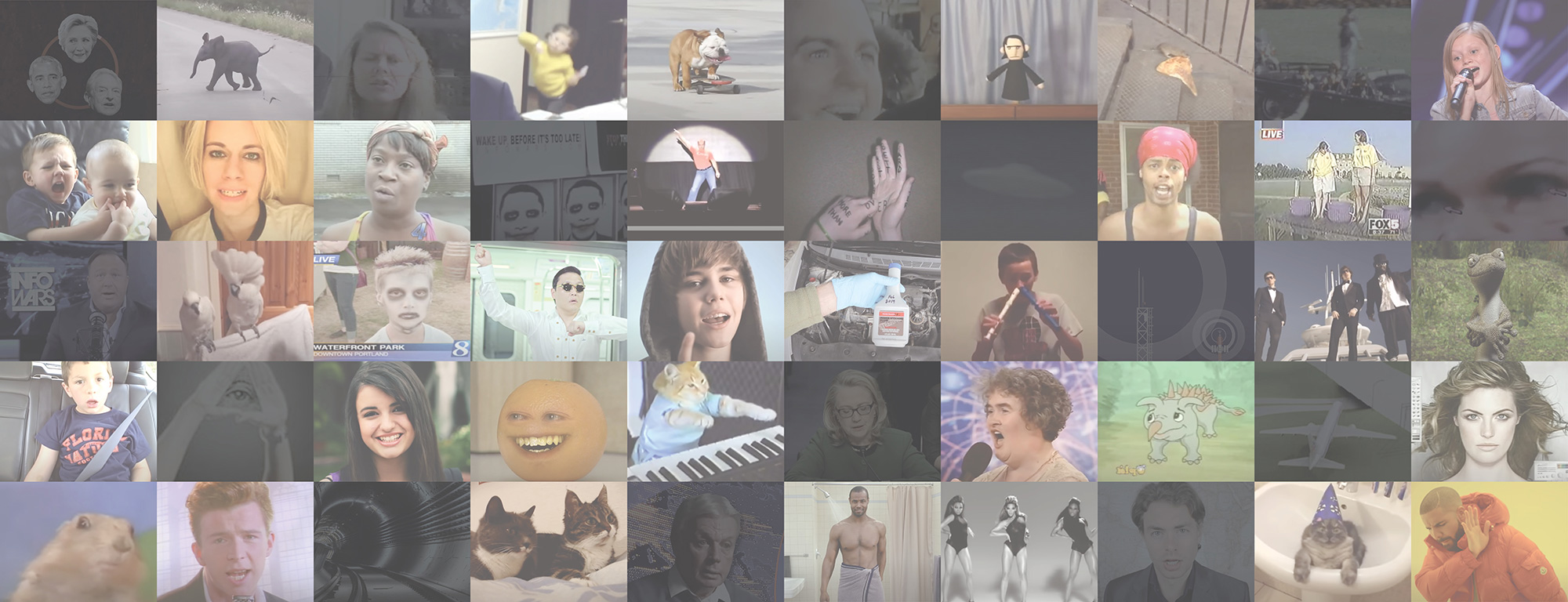

When I first started watching YouTube—in 2006, just before it was bought by Google—it was a fairly intimate place. Renetto (a/k/a Paul Robinett) made a clip with “EXTREME GRAPHIC CONTENT,” in which he chewed a mouthful of Mentos and drank Diet Coke and feigned a gastric explosion. Suddenly he was famous. Boh3m3 (a/k/a Ben Going), a voluble young man with an appealingly crooked smile, was one of the first to reach ten thousand subscribers; he shaved his head for the camcorder and made funny sounds with compressed air. Janemcwhir (a/k/a Jane), a Canadian teenager with a pierced lower lip, talked about her friends’ phobias and celebrated her mild crush on a fellow video-uploader named lightrayface. In one of Jane’s videos from the time, “Sneeze,” she suddenly sneezes. Nothing had ever existed like this. Everyone was talking to everyone else about their lives. We had all become diarists. It was tremendously new and fun and confessional: first-person journalism.

Now YouTube is a million times bigger—an indispensable, life-enhancing tool, and also a source of poisonous neo-medieval yammering. There’s much more to sift through, good and evil. We’re told that after the 2016 elections Google made adjustments to YouTube’s recommendation algorithm, so as not to lead impressionable gun-owning zealots frictionlessly down tunnels of paranoia. No one outside of Google knows exactly what the algorithmic changes were—those are proprietary—but we do know that some objectionable videos were removed and that others were affixed with “information cues,” as Susan Wojcicki, YouTube’s CEO, has called them. Little boxes began to appear below certain postings, with links to relevant articles on Wikipedia, in a feeble attempt to redirect viewers of extreme misinformation—stories claiming that high school shootings are hoaxes, that the moon landing was staged, that lizard-brained blood-drinking space creatures are taking over the world, etc. Things got a bit better.

But a vast amount of incendiary fantasy was still there to be streamed. “Some bad actors are exploiting our openness to mislead, manipulate, harass, and even harm,” Wojcicki wrote on YouTube’s blog in December 2017. She announced that the company had invested in phalanxes of human content reviewers, along with “powerful new machine learning technology to scale the efforts of our human moderators to take down videos and comments that violate our policies.” Those efforts, however, could not forestall tragedy in February 2018, when a man and an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle killed or injured thirty-four people at a high school in Parkland, Florida. Afterward, one of the surviving students, David Hogg, found himself accused on YouTube of being an actor hired by advocates of gun control; conspiracy videos about him rose high on YouTube’s trending list. That summer Alex Jones, who’d raved that Hogg wanted “billions of people to die,” was banned from YouTube, and in January 2019 the company made yet more modifications to its autoplay offerings.

Even so, it remains true today that the more dark, wiggy videos you consume, the darker and wiggier your playlist becomes, until you inhabit a so-called “filter bubble,” while Google makes ad money off of your addictive radicalization. (See Zeynep Tufekci, in the New York Times: “Given its billion or so users, YouTube may be one of the most powerful radicalizing instruments of the 21st century.” And Kevin Roose’s extraordinary front-page Times article “The Making of a YouTube Radical.”) A recent analysis of YouTube’s recommendation engine (“A Longitudinal Analysis of YouTube’s Promotion of Conspiracy Videos”), from the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Information, concludes that the filter-bubble effect declined somewhat following the algorithmic adjustments of 2019 but that now, a year later, “the proportion of conspiratorial recommendations has steadily rebounded.” The authors are troubled by “the ever-growing weaponization of YouTube to spread disinformation and partisan content around the world.” Remember: unlike most news outlets, YouTube is free and open to all contributors—free to watch as much as you want, and free to load up with hours of homegrown creepy content. Anyone with a computer and a quiet space in which to harangue followers can become a David Icke protégé, broadcasting fanaticisms about pedophile reptilian international bankers.

It was the blood-drinking delusion in particular that made me never want to watch a YouTube clip again. I told my editor at the Columbia Journalism Review that I was sorry but I couldn’t write the piece. She countered by asking me if I could simply think about what it was that I’d liked about YouTube in the first place. Try a new search, she suggested. Ignore the psychotic Satan-fearing fantasies—which have, after all, been written about by many competent journalists, who’ve been doing their best to make sense of recent political calamities. Find out instead what today’s monetized algorithm actually gives you. This was good advice. Maybe, I thought, I could even use YouTube to heal the fresh psychic wounds of YouTube.

The more dark, wiggy videos you consume, the darker and wiggier your playlist becomes.

So I tried again. I used a brand-new account, made with a new email address, so that my previous viewing history wouldn’t influence which videos were recommended, in case the algorithm wanted to mine my past clicks. To begin, I seeded the feed with one of my favorite clips, “cockatoo loves elvis,” by Mark Muldoon. In his kitchen, Muldoon sings to a pair of white cockatoos, one of whom is a music lover and promptly fans out his or her head-feathers, then bobs enthusiastically. The other bird, not sharing the mood, sidesteps quietly to the farthest edge of the perch, leaning away, sometimes lifting a claw in warning: I don’t want this right now. “Sometimes you’re the parrot on the left,” says a commenter named stwawbewwy. “Sometimes you’re the parrot on the right.”

YouTube suggested some places for me to go next, one of which was a cat compilation called “FUN CHALLENGE: Try not to laugh—The FUNNIEST cat videos EVER.” A cat fiercely attacks a mailman’s gloved hand through a letter slot, shoving several pieces of correspondence back out onto the porch steps. I laughed; my life had improved. Then I watched “Funniest Pet Reactions & Bloopers of November 2017,” which had some good moments and, honestly, some less good moments. “A camel drinking out of a can,” writes commenter Louise, “disgusting, height of cruelty, treat them with love and respect. Don’t get me started about the elephant on the bike.”

Then, for its own proprietary reasons, the algorithm offered me a playlist called “clean vines for the children of jesus.” I clicked on it. It was a series of ultra-short videos that had lived on Vine, the now defunct short-video sharing platform. Someone screams the names of batteries phonetically: “AA! AAA! AAAA!” A little kid, happily eating an ice cream pop, says, “My daddy has a gold tooth.” Her friend says, “My dad has diabetes.”

I went back to my home screen, where the breaking news of the day, displayed as a row of smaller video thumbnails, was “Biden Talks ‘Presidential Leadership’ in Time of Coronavirus.” Biden says, “Just over a week ago, many of the pundits declared that this candidacy was dead. Now we’re very much alive.” A crowd cheers.

Then something oddly political happened. The next video that the algorithm gave me was a three-year-old monologue by Judge Jeanine Pirro, on Fox News, about why Hillary Clinton used a private email account for her government correspondence. Before it played, an ad came on from the Trump campaign, wanting me to take a survey. Then I got a second ad, for a newspaper with ultraconservative and Falun Gong connections called the Epoch Times: “Are you tired of the media spinning the truth and pushing false narratives?” Evidently YouTube, not knowing much about me yet, wrongly assumed that I was a member of the alt-right. Based on what? Where I live, in Maine, or that I like dancing-cockatoo videos? That I like Elvis? Maybe it was Elvis.

Judge Jeanine’s monologue was bitter and unpleasant. “Bill and Hillary Clinton are the Bonnie and Clyde of American politics,” she says. I clicked the “next” arrow. Now I was given fourteen minutes of Hillary Clinton testifying about Benghazi from 2015. Why?

Returning to the home screen, I mulled over the options there. Should I watch something about a ninety-three-year-old man talking to a judge about his speeding ticket, or an anthology of TV news bloopers, or an arm-wrestling match between a professional wrestler and a little girl named Brielle? Should I watch top basketball dunks, or a comedy bit by Bill Engvall on bathroom etiquette for married people, or Seth Rogen testifying before Congress? Or Ellen DeGeneres’s favorite “What’s Wrong” photos, or a clip of Simon Cowell judging singers on America’s Got Talent?

I chose Ellen, who showed her studio audience a Craigslist photo of an apartment: off to one side someone’s bare-but-blurred bottom is partly visible. “You know what they say,” Ellen tells the crowd. “If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen and take all your clothes off.” Then I clicked on America’s Got Talent. Onstage, a girl named Ansley, perhaps ten years old, begins singing an Aretha Franklin song. She’s good. Cowell stops her and says her background track is horrible. The girl looks downcast. Simon suggests that she sing the song a cappella, no backing track; to fortify her, he offers her some fresh water from an America’s Got Talent Dunkin’ Donuts cup. Ansley resumes singing. Her voice fills the huge auditorium they’re in, as her family looks on anxiously and the crowd claps her a rhythm. “You better think, think about what you’re trying to do to me,” she sings. Simon gives her a thumbs-up. Great.

Next, “Best TV News Bloopers of the Decade.” I clicked and was happy: a weatherman announced that there would be “areas of drist and mizzle.” I then remembered how much I used to love fast-worker compilations: clips of nimble people who can manipulate bricks or packing tape or burritos with amazing speed and precision. There’s the one-armed pizza twirler. The blind barber, who cuts by feel. The floor refinisher with his sweeping arcs of polyurethane. The dance of the window washer at the airport. The bare-chested Ferris wheel attendant who hurls the entire wheel forward, seat by seat. I watched these for an hour. So much strength, so much skill: thanks to YouTube, millions of people see anonymous hands doing what we’d thought were impossible things—newsworthy things.

I searched for Lionel Messi, recalling that several years ago I spent a whole morning watching heroic soccer plays. I don’t know much about soccer, and yet I cheered at Messi’s thrilling goals and passes and feints. “20 Lionel Messi Dribbles That Shocked the World.” “10 Impossible Goals Scored By Lionel Messi That Cristiano Ronaldo Will Never Ever Score.” Then I remembered other lost hours, times I’d watched Russian dashboard camera videos that capture (usually) minor accidents, often in slushy snowstorms: “Best of Russian Driving Fails 2018,” with ten million views. When I searched for them, the YouTube algorithm obligingly followed up with an assemblage of Parkour Fails, in which people flip and fly through windows onto roofs, and fall and skid and survive.

Parkouring from video to video, I began to feel the basic incredulous YouTube feeling, which is this: How can so much leaping life and vitality and energy and tragedy and determination and crazy risk-taking be pouring out of one laptop screen? How can it be available any time I want it? Bodybuilders who push themselves too far and tear their steroid-injected biceps. Pole-vaulters who break their poles and yet go on to set world records. Construction workers on handmade scaffolding who pass bowls of cement by hand to colleagues a level above them. Public freak-outs, dozens of them, in parking lots and liquor stores and fast-food restaurants. Epic scenes of road rage, where people curse and finger-jab through a car window. Thieves subdued by store owners wielding empty cash register drawers. Chiropractors audibly jerking people’s heads around: “14 Minutes of Quality Cracks.” (After every crack, the patient makes a little sigh of contentment.) Public freestyle twerkers with flowery yoga pants and fifty-one million views. Celebrity TV interviews. “I’m on a drug, it’s called Charlie Sheen,” says Charlie Sheen, in a clip from Good Morning America. “It’s not available, because if you try it once you will die. Your face will melt off and your children will weep over your exploded body.” And then there are the thousands of self-help videos. A whole playlist discusses the latest version of the eighteenth-century French adage that the best is the enemy of the good. Now it goes, “Perfect is the Enemy of Done.” Which is so true.

I felt my mind expanding with the limitlessness of what has been achieved and will never be known by any single person, but is nonetheless worth knowing. The endless library of the speaking human face, and the explaining human voice. The ranting, cajoling, contending, confessing, storytelling voice. YouTube inhales five hundred hours’ worth of potentially watchable, listenable material per minute, which is more than seven hundred thousand hours coming in every day. Very little of it, relatively speaking, is about politicians who allegedly feed on human blood to stay young and control the world.

When I’m in a drunk-on-YouTube mood, it’s astonishing to me to think that Netflix can exist, that HBO can exist, that Spotify can exist, that books can exist, that public radio and podcasts can exist. Why read a magazine when you can watch heavy-equipment-fail videos? Cranes teeter and topple and huge logging machines get mired in mud, and it all happens very slowly, at dream-time speed, and nobody is injured (for the most part). Watch a few “wild weather” and “severe weather” compilations and ask yourself if you’re the same afterward. In “15 Scariest Natural Phenomena Recorded on Camera,” typhoons and tidal waves silently ruin communities while people film from balconies and a royalty-free composer named Kevin MacLeod plays sad sounds on the piano.

By now my feed was richer, influenced by what I’d seen and what YouTube’s “deep neural network,” its engine of eternal surprise, figured I would like to see next. It was giving me master bricklayers, outrageous game show moments, cockatoos swearing, “The Gruesome Case of the Papin Sisters,” and, sometimes, left-leaning clips. “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Best Moments Supercut” was in my playlist now, even though I had never searched for AOC. There were also many clips from Fox News, including a blast of opinion from Laura Ingraham, who says that the Democrats are turning the coronavirus into a political crisis. Ingraham plays a sound bite from Rep. Maxine Waters, who expresses the view that the president is a liar who needs to be quiet—that he needs to “shut his mouth.” “Isn’t Maxine nice,” Ingraham says, showing her lower teeth.

YouTube was also suggesting more news bloopers—it could tell how much I liked them, even though I hardly ever clicked on them now—plus some Saturday Night Live bits. Then I was given an outdoor piano player performing “Dance Monkey” on his upright piano on a city street. That piano video, which had eighteen million views, led me to the official “Dance Monkey” video, by a performer who goes by Tones and I, with three-quarters of a billion views. Tones is an Australian woman with a throaty, reggae-like voice, although in the video she’s dressed up as a bearded geezer who wanders around on a golf course blowing golf balls into holes with a leaf blower. After an ad for car insurance—in which a cool man in a leather jacket repeatedly tries and fails to say “Liberty Mutual customizes your car insurance, so you only pay for what you need”—YouTube played a New York Times making-of video about Tones in her early days as a busker, and how she became a massive hit. “People don’t walk past Tones,” her manager says. “No one does.” When Tones first played “Dance Monkey” for him, he remembers thinking, “This is going to be a cracker—like, a proper cracker.” By the time the Times video played the footage of Tones singing “Dance Monkey” at an outdoor concert, I was shaking my head, spluttering with admiration. I felt in the know, even though I was really a year behind.

This is why I love YouTube, despite its documented dark corners, its co-option by opinion hackers and election influencers to trick people into believing in globalist conspiracies of Very Evil People. If you want to spelunk in slippery cave systems of irrationality, YouTube will definitely take you there. For example, on April 1, 2020, Steele, the “adrenochrome” man, posted one of several of his coronavirus conspiracy videos: he now claimed that New York City, a “province of Israel” (or so he said in the comments), had lied about the number of covid-19 deaths as part of a “massive medical simulation.” (Steele’s video was removed a month later.) But if you want to feel how great it is to be alive in this scrambled and feverish moment in history, if you want to know that you’re part of something huge and unstoppable and planetary and singular and unpredictable, something that can fill you with joy and make you want to toss pieces of paper in the air, YouTube will do that for you, too.

Now please excuse me while I watch this cockatoo freak-out compilation.

Nicholson Baker is the author of many books, including his most recent, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act.