On February 29, Washington State health officials announced what they believed to be the first death due to the novel coronavirus in the United States. By March 31, the official national death toll stood at 3,173. It was a larger number, news outlets noted, than lives lost in the September 11 attacks. A month later, on April 28, the US confirmed its millionth covid-19 case and logged its 58,365th death from the virus. Now we had passed American military deaths in the Vietnam War. By May 27, the coronavirus had killed more than 100,000 people in the US.

As outlets ticked off the grim numerical milestones, photojournalists struggled for better ways to convey the devastation. The definitive image of the crisis has eluded us.

The Great Depression had “Migrant Mother,” and World War II “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima.” The aids crisis had “The Face of aids,” depicting the death of David Kirby; 9/11 had “Falling Man”; and the war in Syria has Alan Kurdi. But now, with the country in hibernation, and hospital patients largely off limits, how can photographers give meaning to the incomprehensible numbers?

“War is 95 percent boredom and 5 percent sheer terror, from a journalist’s point of view,” says David Hume Kennerly, who won a 1972 Pulitzer Prize for his feature photography of the Vietnam War. CJR sat down with Kennerly and three other esteemed photojournalists from that conflict, Art Greenspon, Robert Hodierne, and David Burnett, to ask what lessons we can take from Vietnam to cover today’s invisible killer and the absence of public suffering.

The conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

We just passed one hundred and fifty thousand deaths in the States. Why are those last fifty thousand deaths less noteworthy to us than the ones between ninety thousand and one hundred thousand?

Art Greenspon: You know, covid is being covered like a war, but a war is different, at least in my experience of the Vietnam War. It’s numbers and tactics and troop movements. With the virus, journalists have focused on the number of hospitalizations, number of new cases, number of tests. Just numbers, numbers, numbers. And credit Governor Cuomo for referring to that all the time in his press conferences. “We lost another thousand people today.”

Robert Hodierne: About the fourth word out of [PBS anchor] Judy Woodruff’s mouth every night is the new body count. This is different than war. There are no funerals.

When a guy was killed in Vietnam, there was a big hoopla as he came home. The flag-draped coffin, and the bugler playing taps. The family was given the flag, and everybody would gather around for the burial. It was a very traditional way of mourning.

covid, you take your loved one to the hospital, and you never see them again.

David Hume Kennerly: I think the problem with numbers in general is they don’t relate to the actual person. It’s something I’ve thought about my whole career. When I first realized that, I think, was one of those big cyclones in Bangladesh or East Pakistan or whatever it was at the time, you know, like five hundred thousand people killed. No way to relate to that. I don’t think we understand the immensity of this, and everybody uses the same markers. Now we’ve reached the death toll of Vietnam. Now it’s more than Iraq and Afghanistan put together. It’s all b.s.

Nick Farenga retrieves the body of a covid-19 patient from a refrigerated trailer outside a hospital. (Photo by Philip Montgomery, courtesy of the New York Times.)

What is missing in our photographic coverage so far?

Kennerly: A lot of the funerals happen and the families can’t even be there, so basically what is stripped away is people grieving at a grave site. Like the great moment with Jackie Kennedy at the grave site, stuff like that. You’re not going to see it.

I haven’t been doing it because I’m past seventy years old. I’ve just tried to avoid it. I’ve hung my ass out enough without getting whacked by some invisible presence, you know, and possibly giving it to somebody else. But there are a lot of great photographers out there trying to make that picture, and I think it’s probably most frustrating to them because we don’t have a signal moment.

If you can stay alive doing it, it’s easier to cover a war with palpable action right there in front of you. Smoke, fire, and fear.

I know the people who took the greatest photographs ever. Eddie Adams’s “Saigon Execution,” Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl,” Joe Rosenthal of the Iwo Jima flag raising. And those are pictures that are forever in your heart and soul. And we don’t have that moment right now.

A perfect recent example of the power of the image in a situation like this would be the Syrian refugee kid on the beach. Or the El Salvadorean father and child who had drowned trying to cross the border river. I don’t think one of those kinds of images has been made yet showing the impact of the coronavirus plague. A majority of people are dying in nursing homes and hospitals. It’s a medical atmosphere.

If you can stay alive doing it, it’s easier to cover a war with palpable action right there in front of you. Smoke, fire, and fear.

David Burnett: There is no cataclysmic equivalent of bombs dropping, or grenades going off, or rifle fire, or firefights. It’s kind of anti-noise. It’s so much more internal and infernal. We are groping to try and find something that equates to those numbers, to give a sense of the extent to which this has taken over and destroyed the lives of so many people. It’s not an easy thing to do if you’re the photographer. You’re trying to give a representation of something that’s, in a way, very physical. But the feeling is kind of metaphysical—you’re trying to imply something, to make people understand it, without overdoing the dead-body part. It’s about trying to find something that’s representational.

In Vietnam, there were these visual moments of high panic and stress in combat or the moments after combat when you could see the effect of it. And here it’s all been the hospital. There’s probably a little bit of alarms going off if you’re in the ICU or something, but essentially, the whole thing is existing on a level of quietude that is very different.

Hodierne: The iconic imagery from Vietnam that involves casualties were like the Art Greenspon photograph of the jungle clearing. Everybody has their heads down, and one guy is raising his arms up. John Olsen’s photograph from Hue during Tet of a tank with dead and wounded guys arrayed on it is a pretty powerful image of death in combat. But I don’t know how to compare the two. I think the photographers who are going into these hospitals are very brave. Taking pictures in a combat situation is pretty scary and pretty dangerous. But at least you sort of know where the danger is coming from. You know where the gunfire is coming from, how to take shelter, how to protect yourself. In the hospital, no matter how well dressed you are in PPE, it’s still a risk. How do you clean your cameras? I’m glad I’m not having to do that.

February 18, 1967. Pvt. David Wood stands watch as the village of Lieu An burns. (Photo courtesy of Robert Hodierne.)

Greenspon: Where’s Life magazine? Where’s Jimmy Breslin from the Daily News? They used to do personal essays, you know, of great photography. I think when you’re remote filing, and doing things on the phone, and that kind of becomes the culture, you’re going to get journalism from thirty thousand feet at best. How many photographers and journalists have lost their lives covering the covid epidemic?

It was typical in Vietnam, too. There were six hundred journalists, but most of them didn’t go into the field. They were happy to go to the Five O’clock Follies and cover it from a distance with the handouts and the numbers.

My kids are twenty-one now. I keep telling them: You have to pay attention to this, this is the biggest story in your life, this may be the biggest story in my life. I keep trying to think back to 1968 and to this series of traumas. You know, the demonstrations, the anti-war protests, and then the Martin Luther King assassination, and then the [Robert] Kennedy assassination. There was this series of gut punches.

But this is different. This is somehow more terrifying. We’ve been focusing on the big picture, the pervasiveness of this. But the secret to an iconic photograph is to make it very personal and express the larger picture through an intimate portrait of a situation.

A Marine sniper discovers the body of the North Vietnamese soldier he has just shot. Hue, Vietnam, 1968. (Photo courtesy of Art Greenspon.)

In May of 1968 I was shot in the face in a cemetery in Saigon the same day that Co Rentmeester (Life) was wounded and Charlie Eggleston (UPI) was killed. I guess we got too close. Journalists have always suffered heavy casualties covering risky stories. Maybe they are today too, but I’m not reading about it. Why?

I don’t see those stories that tell the really human content. When I was a broadcast journalist, my editors kept saying to me, What does it mean to the guy in the street? And when you do journalism from thirty thousand feet, you don’t connect with the guy in the street. Now, this is devastating, the links with systemic racism. covid is devastating our Black and brown communities. Who’s telling that story from inside the community? All right, it’s very difficult as a photographer to get up close because of hipaa and because of patient confidentiality, but I think a reporter can get inside and maybe a photographer could get inside.

Somebody has got to tell the story of the firehouse, and the EMT, and the church doing the testing, and the people dying in fifth-floor walk-ups that are a hundred degrees. Who’s telling those stories? Where’s the story from inside the nursing home, about the people waiting to die and not being with their loved ones? We’ve seen the picture from outside, you know, of the people trying to get inside. But what about the story from the inside, those old people? What is it like to be an old person?

Pauline Crum, a resident at Menorah Park, reaches out and touches the glass as she talks to her daughter, Connie Nusbaum. March 20, 2020. (Photo by Gus Chan, courtesy of the Plain Dealer)

Breslin would be in that firehouse and he’d be rolling with those ambulances and fire trucks that are going to get somebody out of the fifth floor on a ladder because they couldn’t get him down the stairs or something. He’d be telling that story. And it would be very emotional. It would be very connected. So maybe that’s what I’m talking about, is connectivity.

Now, that may have to do with how the structure of journalism has changed. I’d really have to ask myself whether I’d be willing to risk my life to get that iconic photograph of covid. Because what are the rewards? It’s tough to make a living as a photojournalist these days.

War is 95 percent boredom and 5 percent sheer terror, from a journalist’s point of view.

Sometimes the definitive photograph from an event doesn’t emerge until later. With 9/11, it wasn’t immediately clear that “Falling Man” was it.

Hodierne: There are photographs from the Vietnam era that I think everybody knew at the time. The little girl was burned, running naked toward the photographer. I think everybody recognized that that photograph was really important. And the photograph of the Saigon police chief blowing the brains out of a Viet Cong prisoner. You knew instantly. From the Second World War, “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima” was immediately published in every newspaper in the country, on stamps and everything. There wasn’t any waiting on that one. But I think you’re right about this. I have yet to see the definitive image, the one that I think, you know, we will look back on five years from now and say that got it like the “Falling Man” got it.

I wonder if part of the challenge of capturing the definitive images of the pandemic is that so much of the suffering is internal. Or that our faces are covered?

Hodierne: Well, yeah, but the eyes. In some ways, it makes you focus even more on the eyes. When you look at all the best war pictures, it’s the eyes of those guys. It’s what we used to call the two-thousand-meter stare. You know, David Douglas Duncan. Photographs of Marines in Korea. It’s the eyes that get you.

Or I think that you could still do really good portraits of people with their masks on if you stand eight feet away with a 105 millimeter lens. Ask him to take the mask off. The mask isn’t protecting them, it’s protecting you.

Kennerly: With Ebola, the fact that you were on the line between life and death was much more palpable. Here, all the major players are behind protective clothing: goggles, masks. So you can get some intense intensity in the eyes of the doctors and nurses and health caregivers and all that. A sterile atmosphere does not a good picture make.

Burnett: You realize how much we rely on looking at someone in their eyes, in their face, and that becomes a great communicator of what people are undergoing, what they’re thinking. And if masks are in place—well, I just have yet to see a mask picture that really touches me.

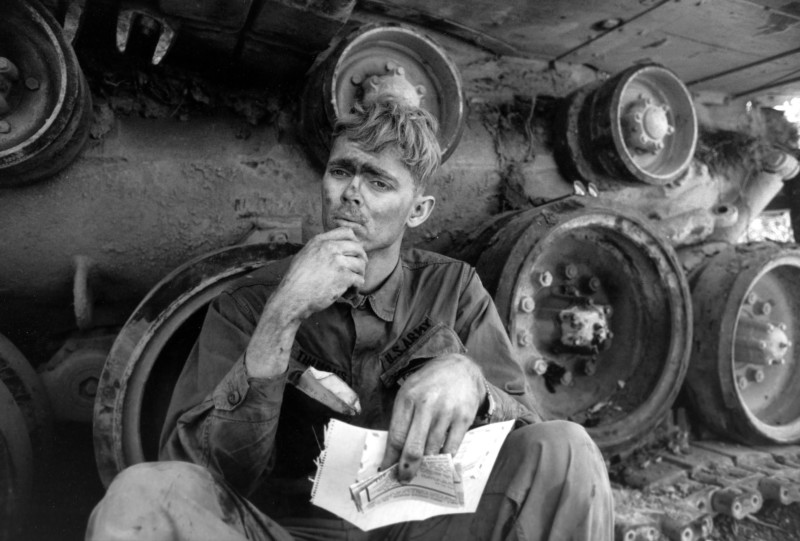

April, 1971. Fatigued GI at Lang Vei. (Courtesy of David Burnett/Contact Press Images.)

A lot of journalists feel story fatigue has become a real challenge with covid coverage. Did you ever have that problem with Vietnam?

Burnett: I only got to Vietnam in 1970. I’d just turned twenty-four when I went out there. It sounds young, but I was older than probably three-quarters of the soldiers. Even then it was still a big story. It was still a story that demanded attention. In ’71 there was the invasion of Laos, in ’72 the Easter Offensive. It was a story that just kind of kept going; every week it was still the big story.

This is clearly a gigantic story with all these different elements. You’ve got people dying. You’ve got people out of work. How does that affect the economy, and is the economy coming back? We might be tired of it, but it affects everybody in every aspect of their lives. We might be tired of it. It’s not going to be tired of us for a while.

Kennerly: It’s really not how you dealt with it when you were in Vietnam. The bottom line was you knew when you went up the road you could get whacked, unlike this, where you could go to the grocery store or go to a protest out on the street and catch the bug.

The fatigue of covid was replaced by this other big story. People don’t like hanging out in their house. And people are unemployed now and don’t have money. But now it’s about the killing of George Floyd, which is a huge story. You have this tectonic shift; people have the emotional impetus to go out and protest. A picture cannot necessarily tell that story in one frame. It’s too spread out. It’s too big, in a way.

The May 24, 2020, front page of the New York Times marks 100,000 US covid-19 deaths with short obituaries for one thousand of the dead. (Courtesy of the New York Times.)

What visuals have worked best in the pandemic so far?

Greenspon: The front page of the New York Times when we hit a hundred thousand deaths. That hit me like a ton of bricks. The thing that was so brilliant was those personal comments. There was someone for every reader to connect with and be delighted, or saddened that they never got to meet.

Hodierne: Some of the pictures of the hospital workers sitting exhausted with their face in their hands. Some of the photographs of elderly people in nursing homes with their faces pressed to the window, looking at their grandkids—I think those are powerful and enduring images.

Burnett: The Philip Montgomery series, shot in a funeral home in Brooklyn, for New York Times Magazine. Just the guy from the funeral home, surrounded by all these bodies. It was an ultra-quiet moment, nothing loud about it, just the sense of the devastation.

Also in the New York Times, Fabio Bucciarelli did this amazing, like a Renaissance-era picture, of this old guy dying in bed, surrounded by his family. I mean, like something that had been put together for a Renaissance painting. There’s just a level of quiet now.

Cenate Sotto, Italy. Claudio Trivelli, a covid-19 patient, is resting in his bed after being seen by the IRC volunteers. (Photo by Fabio Bucciarelli, courtesy of the New York Times.)

Kennerly: I think the early images that made the impact on me really were the mass graves. Bulldozers digging the ground out there, putting bodies in refrigerated trucks, all lined up. And you know there are bodies in them, it’s just not a very dramatic photo. Visual doesn’t always intersect with the impact of the story.

There have been a lot of really good ones coming out of the demonstrations, of course, because you’ve got signs and passion and all that. Some people wearing masks and others not.

The covid crisis, although monumental, is just plain harder to illustrate. But it can be done, and the Joshua Irwandi photo from Indonesia for National Geographic is a good example of an excellent coronavirus pandemic photo, and should be a Pulitzer contender. It’s the body of a suspected covid-19 victim, wrapped in plastic in a hospital room—the antithesis of fiery protest coverage. It is quiet, lonely, and chilling. It shows someone who most likely died without family around, as so many thousands have. It illuminates the worst side of the pandemic. It’s the power of one. This image is a vivid reminder that sometimes the best illustration of a story is away from the action.

With all the challenges we’ve discussed in mind, how can we remedy the difficulties visualizing covid?

Greenspon: If I was photographing now, I’d go to Brazil, because I think it’s possible to get the numbers, and the mass, to get that one picture that shows the scale, as well as the tragedy and suffering. That’s a key word, suffering.

To make an iconic picture, you have to relate to the people that you’re photographing. When the heart gets filtered up through the camera, it allows you to see things you might not otherwise see. I have tremendous compassion for the people of Brazil and some of the other countries that are going to perhaps be destroyed. Poor people in those countries have to be suffering incredibly. It’s bad enough in this country that American citizens who are poor have to suffer. But there is no hope if you live in Brazil.

I think it would be easier to photograph in Brazil or another developing country because of looser restrictions. It might be more dangerous for a journalist. You’re more likely to get into a ward with a hundred people in it. Maybe catch a priest walking through. It seems to me that there’s a spiritual component to this.

We are suffering as a nation. We are suffering as a world. We are suffering from all kinds of biases and environmental issues. The word that comes to mind is agape. It comes from the Ancient Greek term for love, but now agape means in awe. And that’s the way I feel about the virus. I am in awe of what’s going on in the world. I am loving and compassionate for the suffering.

This tremendous isolation. And that’s what would be in my heart if I went out to photograph. The sense of aloneness and this incredible suffering.

What does it mean to have covid? I only know, really, from Chris Cuomo, who did his show when he had it. And Brooke Baldwin. But what does it mean to have the virus if you’re sixty-five years old and overweight? I would be trying to tell the story of somebody at home, afraid to go to the hospital.

I have compassion for the photographers, too, because they’re not allowed in anywhere. So you’ve got to go make your own story. You’ve got to go hang out in the poor communities. The zip codes that they’re focusing on now, those churches where they’re doing the testing would be fertile ground. That’s got the spirituality aspect of it, and you got that subject matter who are suffering.

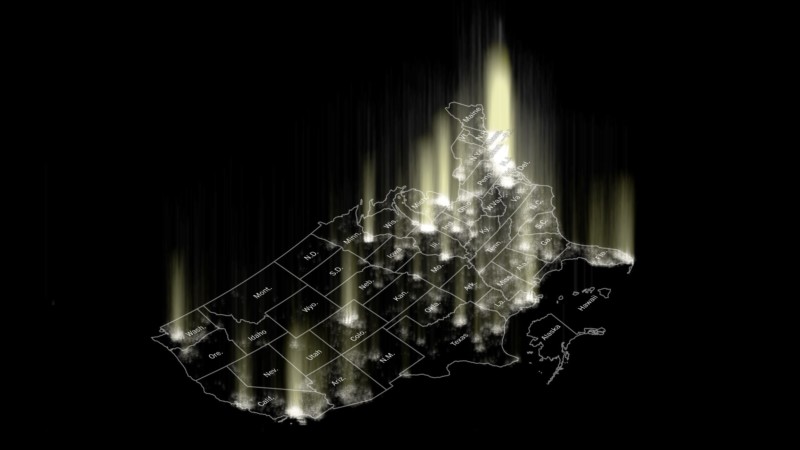

Map illustration by Lauren Tierney and Tim Meko. (Courtesy of the Washington Post.)

Hodierne: Did you see that Washington Post graphic? It looks like it’s at nighttime, a map with the beams of light coming up from different locations on a map of the country? The spotlights are brighter and bigger in areas where more people have died than others. It’s a beautiful piece of work. I could see doing something like that and animating it.

If I were the editor of a local newspaper, I’d be hiring some kid just out of art school. I’d say, Go wild, give me your best ideas.

Greenspon: I have another thought. There’s another story that’s not being told, and I know this because I suffered from PTSD for forty-odd years, only recently being relieved of it.

These nurses, when they hold a cellphone up to the dying patient’s ear, and it’s their loved ones saying goodbye, it’s not only traumatizing the family. It is traumatizing that nurse, or doctor, or nurse’s assistant. And that’s happening day after day after day. These people are going to have real issues going forward.

I’d be hiring some kid just out of art school. I’d say, Go wild, give me your best ideas.

Looking back at Vietnam coverage, what pictures might be useful to guide covid photographers?

Greenspon: I have a picture in mind. It’s a picture of a Marine sniper coming across the body, in the foreground, of a dead North Vietnamese soldier who he had just shot. He’s got a look of horror on his face; he’s about nineteen, but he looks really seventeen. It’s Hue, 1968. It’s just the horror of war. It’s young kids killing.

Burnett: I think of Don McCullin’s picture of the Marine in Hue who’s kind of got that thousand-yard stare, just completely worn down by the abusive power of being in combat that long.

Hodierne: In June of 1969, Life magazine published 217 photographs: all the young men who had died in one week in June. You just kept turning the page. Many of them were high school yearbook pictures with their crew cuts and their black-framed glasses. Some have them in their high school graduation gowns, others in stiff, formal portraits, posed in front of the flag, that were taken when they graduated from basic training. All these young, young, young faces, page after page after page, was very powerful.

Khe Sanh, Vietnam, 1971. (Photo courtesy of David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images.)

Kennerly: I don’t think I ever got a great combat photo in Vietnam. For one thing, if you’re under heavy fire, it’s really hard for practical reasons. It’s been done. But I won the Pulitzer Prize for pictures that were right before or right after the action. One of the photos that wasn’t in the Pulitzer portfolio, but it was taken that same year, in 1971, was a soldier with his shirt off and a cross dangling from his neck, sort of over a machine gun. You can make a really good picture of a quiet moment. War is 95 percent boredom and 5 percent sheer terror, from a journalist’s point of view.

I think any good photographer has to be able to deal with the 95 percent.

Amanda Darrach is a contributor to CJR and a visiting scholar at the University of St Andrews School of International Relations. Follow her on Twitter @thedarrach.