The neighborhood of Bebek, in Istanbul, is a former fishing village nestled within one of the most picturesque bays of the Bosporus. In October I visited the seashore, where hotel bars and teahouses line the bank; fine-boned, finely dressed people sat and smoked and watched tankers go by. In the fall, the salmon-gold light over the water was so beautiful that it was easy to forget I was in a country where darkness is descending everywhere.

Murat Yetkin, a 59-year-old journalist, had snagged us a waterside table, where he was drinking tea and writing in a notebook. He was just finishing his sixth book of nonfiction, A Book About Spies for the Curious. A week earlier, he had resigned from his job as editor of the Hürriyet Daily News, the English-language arm of Hürriyet, one of Turkey’s largest and most important dailies. “At least we experienced what it meant to be a journalist,” Yetkin said. “I feel sorry for these young people who could not and cannot.” Hürriyet was one of the many Turkish newspapers recently purchased and summarily dismantled by the most prominent family in Turkish media, the Demirörens.

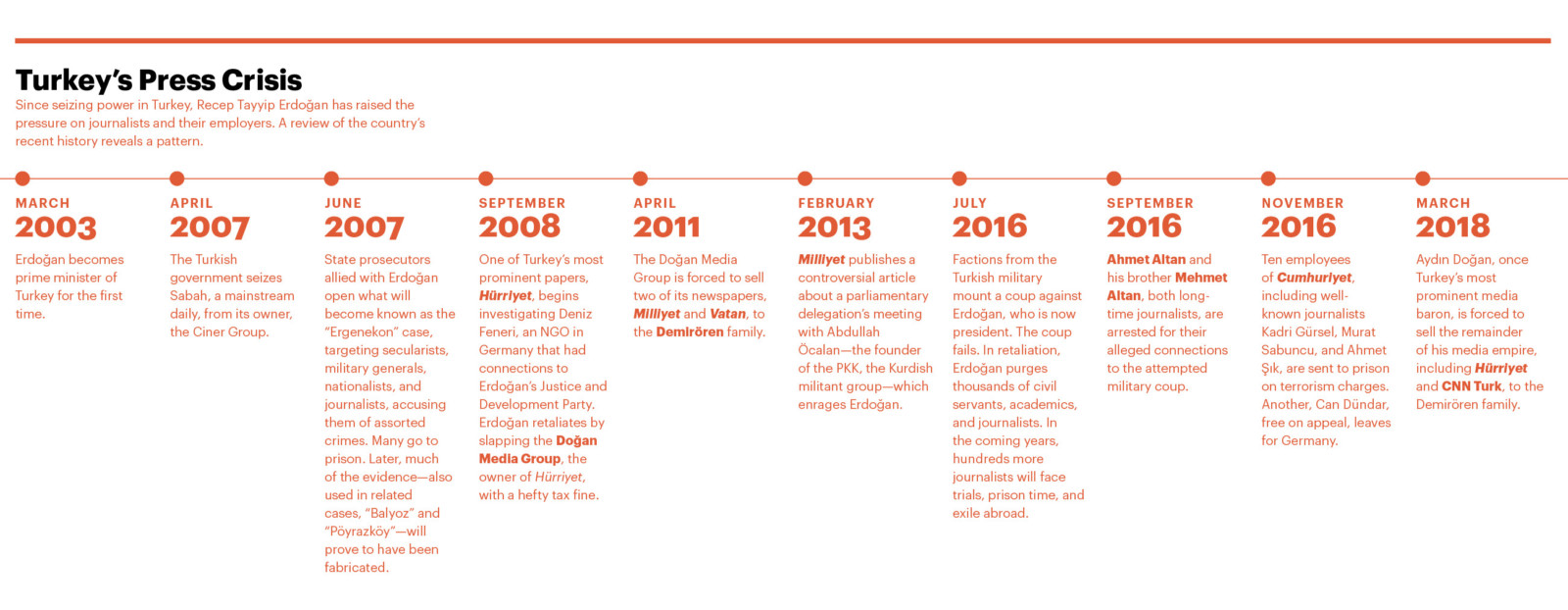

In the past seven years, the Demirörens have come to oversee about a third of Turkey’s media outlets, including one of Turkey’s most watched TV stations, CNN Türk. The family had been involved in newspapers on and off since the seventies, but it wasn’t until a recent antidemocratic scandal that their name became internationally recognized. Last March, the man who was once Turkey’s most powerful newspaper owner, Aydın Doğan, announced that he would sell off his flagship paper and several other entities to the Demirörens, staunch supporters of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The sale was universally regarded as the Turkish media’s final gasp, mostly because everyone knew that the only reason it could have happened was that Erdoğan wanted it to. Newspapers began referring to Erdoğan Demirören, the family patriarch, as Turkey’s Rupert Murdoch.

But that moniker misrepresents how much Erdoğan, an Islamic conservative, has transformed Turkey’s media since seizing power, and how much he has remade Turkey as a whole. The Murdochs, especially in the age of Donald Trump, are kingmakers; Erdoğan would never permit anyone else to have that much influence. Instead, the Demirören family has become something far stranger, and far more emblematic of the Erdoğan era. As an academic (who asked not to be named because of a pending court case) explained to me, “The Demirörens did not get into the media business on their own—they found themselves compelled to get into it.” In essence, the Demirörens work for Erdoğan. In Turkey, the only kingmaker is the king.

Yetkin—bespectacled, preppy, and mirthful in spite of our depressing topic of discussion—was the most recent casualty of a particularly bloody interval of high-profile firings and resignations at Demirören media organs. He had spent the aughts—a heyday for Turkish journalism—as Ankara bureau chief at Radikal, one of Turkey’s most progressive newspapers. Hürriyet and Radikal were like the New York Times and the Washington Post of Turkey, and there used to be lots of competition: when I moved to Istanbul, in 2007, I marveled at the diversity of the national newspapers piled up at supermarkets—Milliyet, Sabah, Zaman, Cumhuriyet, Star, Akşam, BirGün, Habertürk, Vatan, Sözcü, Posta, Yeni Şafak, Türkiye—a sight all the more striking given the declining number of publications in the United States. They represented a range of political beliefs and rhetorical styles, from serious, even academic journalism to raucous tabloids with half-naked women on the front page.

But around 2008, after Erdoğan won his second term, the Turkish media became the first sacrificial victim of his deepening authoritarianism. In the years since, the most vocal and talented journalists at these papers have been put on trial, thrown in jail, or chased out of the country. (The Committee to Protect Journalists found that 69 Turkish journalists were jailed in 2018, but previous years had seen that number shoot into the hundreds.) Reporters have been hounded and harassed on social media; sometimes they have been arrested for their tweets. They have been forced to censor themselves. They have been left careerless. They have feared for their lives. And they have watched their profession become a farce.

Until now, a paper like Hürriyet Daily News was never a particular concern of Erdoğan’s—he always cared much more about what was said in the Turkish language. But a time had come in which even HDN was deemed too critical of Erdoğan, somehow. As Yetkin wrote in a farewell letter, “I simply do not want to take part in the final stage of the transformation of Turkish media as we know it.” The stage to which he’d referred was the Demirören Stage.

The story of the Demirörens’ ascent illustrates how a country with democratic aspirations can so quickly succumb to autocracy, and how ordinary people find themselves conscripted into—or willfully joining—the autocrat’s cause. “Turkey,” Erdoğan Demirören said in 2015, “can only progress with an authoritarian regime.”

Erdoğan Demirören was born in İnegöl, in western Anatolia, near the city of Bursa, and moved to Istanbul in the fifties to attend a French high school. In 1956, he began playing soccer for Emniyet SK and Beşiktaş, two of Turkey’s major teams, but after his father died, in 1957, he took over the family business: importing auto parts. Demirören was then 19 years old. By the seventies, he moved into cylinder gas—the kind sold to households for cooking and heating—and started investing in other sectors, too, including media.

In those years, Turkey’s mainstream press was dominated by four families. For the most part, publishers were former reporters or editors who loved the business. But they were also dependent on a state-run economy, especially for basics like paper, and thus were wary of upsetting Turkey’s ruling generals or the governing party, all of whom regularly intervened in the papers’ affairs. When discontented, the military complained to editors in chief. Newspapers were shut down, copies confiscated. Journalists were sent to prison. Turkey’s media was never free.

Yet newspapers of that time could be robust—radical, antagonistic, serious. A singularly crucial figure ushered in an era of vigilant journalism: Abdi İpekçi, the editor in chief of Milliyet, who “brought a new mentality of journalism to the country,” as Soli Özel, a newspaper columnist and academic, told me. “He elevated the form, introduced a higher standard of reporting, and had an outward look towards the world.” Another journalist referred, admiringly, to the “Abdi İpekçi school of journalism.” İpekçi supported reconciliation with Greece, Turkey’s enemy at the time, and advocated for human rights. Milliyet, owned by the Karacan family, became the gold standard for journalism in Turkey, the educated person’s paper.

“The Demirörens did not get into the media business on their own—they found themselves compelled to get into it.”

Erdoğan Demirören owned 25 percent of Milliyet, one of his many investments. In 1979, however, Aydın Doğan, then a young businessman, bought the paper in its entirety, adding it to his holding company. At the time, Turkey’s politics were in chaos, and assassinations were frequent. One night, on İpekçi’s way home from the office, a pair of ultranationalists shot him to death.

In 1980, Turkey’s generals staged a military coup and began transforming the country. The coup mainly targeted leftists, and among the generals’ decrees was an economic-liberalization plan that would eventually spell the increased privatization of the media—a new game in Turkey, at which Doğan excelled. For a time, the Demirörens faded from the media world.

Nevertheless, the Aydın Doğan period of Turkish media history is crucial to the story of the Demirörens, because it was Doğan whom Erdoğan called on Demirören to replace. Doğan, never a newsman himself, took a liking to the business of publishing and spearheaded an arrangement that would become typical of Turkish holding companies that owned press outlets: the media was used as a way of securing favors for his other businesses, including energy, steel, and cars. After Milliyet, Doğan added two more major newspapers to his holdings: the more tabloid-style Hürriyet, which quickly became Turkey’s most important paper, and Radikal, which was relatively liberal and progressive. “Doğan loved journalism,” a reporter who worked for him said. “Journalists would drop by his house and play backgammon and gossip with him. He was educated by his columnists. They were like his sons.”

Throughout the eighties and nineties, the military continued to intervene in newsrooms. Doğan did, too. “Some of my colleagues tend to perceive the end of free journalism as the moment when Doğan papers and stations sold to Demirören,” Yetkin said. “Given the political atmosphere, I perceive it rather as Dante’s layers of hell.” During the Doğan years, countless journalists and writers had court cases brought against them for “supporting terror” or “insulting Turkishness” (including, much later and most famously, Orhan Pamuk, the Nobel Prize–winning novelist). Sometimes, Doğan would fire his staff members for their views.

Illustration by Axel Rangel García

Still, the stakes involved in writing about sensitive subjects weren’t nearly as high as they are today. “An editor may have gotten calls from the military, but he wouldn’t have been vetted and appointed by [them],” another journalist who worked for Doğan’s papers told me. “Doğan sometimes would ask columnists to stop focusing on what they were writing. He would say, ‘Oh, no, you are going to ruin my relationship with the government! Are you going to run it?’ And his editor would reply, ‘Yes, sir, we are; we have to.’ And he would say, ‘Okay.’ ”

Turkish newspapers could be lively and vociferously critical. Journalists held prime ministers to account and picked fights with politicians they detested. Editors were power players. A major paper like Hürriyet or Milliyet could make or break a candidate, and the proliferation of newspapers created a competitive atmosphere. Reporters wanted scoops. They wanted to win.

The newspapers’ owners had a stake in these fights. It was well known in Turkey that publishers like Doğan had gotten into the newspaper game for the political influence it could afford them. “In those times, the papers were really pointing fingers at the government,” Yetkin said. “Not only in the form of news, but sometimes as manipulation to influence the government.”

In certain cases, the newspapers championed antidemocratic forces, particularly when writing about the historical oppression of Kurds; the military’s war with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, known as the PKK (it would be hard to find leftist Kurds who had much affection for the mainstream press during this period); and the feuds with Islamists. In 1997, worried about the growing influence of Islamists in the country, military generals executed another coup, which newspapers like Hürriyet supported. Not for the first time, some readers would accuse the papers of being overly ideological, elitist, and against democracy.

In the wake of the coup, Erdoğan, who had been the mayor of Istanbul, went to jail. One of the most famous headlines of the time—a headline that Erdoğan’s supporters bring up to this day—was “Muhtar Bile Olamaz.” Appearing in Hürriyet after Erdoğan’s sentencing, it translates to “He Can’t Even Be a Neighborhood Councilman.” Religious Turks would never forget 1997, and Erdoğan, who loves a good grudge, would never forget “Muhtar Bile Olamaz.” He would be able to avenge the insult once he became prime minister, in 2002.

In his early years as prime minister, Erdoğan was still beholden to, even dependent on, journalists, in particular, liberals who might be sympathetic to his pro-business, pro-human-rights, pro-Western rhetoric. On the heels of Turkey’s financial crisis, in 2000, the International Monetary Fund had put in place an economic-stabilization program; the country was recuperating. Erdoğan instituted reforms and negotiated with the European Union. Most newspapers disliked him anyway, but many journalists shared his desire to become closer to Europe. In those years, reporters at Doğan papers continued to suffer more from the military than from the Erdoğan administration.

But that didn’t mean that Turkish media and the AKP—the Justice and Development Party, Erdoğan’s camp—didn’t have other disputes. In the first years of the AKP government, several headlines and articles would injure Erdoğan’s pride. One piece described Binali Yıldırım, Erdoğan’s minister of transportation (and, later, his prime minister), holding a lunch meeting with a group of men while Yıldırım’s wife ate alone. This kind of treatment of women was exactly what many Turks feared about a political party with ties to Islamism; the spotlighting of such a controversy in the media was what many religious Turks disliked about the press. Özel, the journalist and academic, told me, “Of course, shame on them,” referring to the men who made the minister’s wife eat alone. “But also: that photo was meant to be humiliating.” The early years of the AKP threw Turkey into a full-blown culture war not unlike those that erupt in the United States between the Christian Right and the secular Left.

In 2007, riding high on a resurgent economy, the AKP won its second election, as well as a majority in Parliament. It would mark the beginning of the party’s turn toward authoritarianism. That year, the Turkish state seized Sabah, a mainstream newspaper, from its owners, the Ciner Group, and eventually encouraged a sale to a family close to Erdoğan’s administration. The government claimed that the Ciner Group had engaged in financial malfeasance and accumulated too much debt—charges that struck many Turks as plausible enough, given the corruption of the nineties, an era from which the country was only lately emerging. But observers sensed that it was the AKP’s first step toward controlling the media. “If newspapers in the nineties were instruments to get political advantages,” explained Andrew Finkel, a journalist and a founder of P24: Platform for Independent Journalism, “by the late aughts, they became a tax paid by people who wanted to work with the government.”

The next year, in 2008, Doğan’s Hürriyet began investigating Deniz Feneri, an NGO in Germany that had connections to the AKP. Hürriyet claimed that it had been using tens of millions of dollars for corrupt purposes. Erdoğan was outraged by Doğan’s effrontery and, according to contemporaneous accounts, suspected that Doğan was trying to force him into deals that Doğan had been seeking. In response, Erdoğan slapped Doğan with a $3 billion fine on trumped-up charges of tax evasion—a punishment thought to be manufactured to cripple Doğan’s empire.

To escape the fine, Doğan agreed to sell off some of his assets. He was forced to part with Milliyet, once the pride of Turkish journalism, as well as a smaller paper called Vatan. The publications were to be bought by the old, pre-1979 owners, the Karacan and Demirören families. By then, Erdoğan Demirören’s son, Yıldırım, was running the Turkish Football Federation and had grown close to the prime minister, who had invested heavily in soccer. Yıldırım had gotten to know a number of reporters, many of them soccer enthusiasts. Some liked him. In 2012, when Yıldırım hired a journalist named Derya Sazak to helm Milliyet, he told Sazak: “We don’t know newspapers—it’s not our business—but with your help we could get Milliyet back on its feet.”

Most journalists and experts I spoke with don’t perceive any particular political leanings in the Demirören family, which includes, in addition to Erdoğan and his son Yıldırım, a daughter named Meltem and another son named Tayfun. Nor are the Demirörens as religious as Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Journalists who have gotten to know the family did say, however, that the Demirörens have longed to be accepted by Istanbul high society. Like many aspiring Turkish businessmen who came from the provinces, Erdoğan Demirören—an unassuming man with a rectangular face, a wide, flat nose, and fringes of white hair that hung in flaps—could not claim an elite background or education, whether at one of Turkey’s best universities or at colleges abroad, as could many members of Istanbul’s old-school upper class. His occupation, as owner of a cylinder gas company, brought with it negative associations: in Turkey, a tüpçü, or gas-can seller, is stereotypically thought of as being uneducated and unskilled.

Over the decades, Demirören’s company expanded into the mining, energy, and construction sectors. He steadily acquired one of the biggest and most important art collections in Turkey, renowned particularly for its Ottoman calligraphy. He bought the fanciest golfing club in Istanbul. He owned a yali, or mansion, with an address on the Bosporus, near the rest of the wealthy old Turkish families.

His children and grandchildren have enjoyed the trappings of the one percent. In April, Yıldırım’s daughter, Yelda, married into a construction and media family close to President Erdoğan. A week after, the internet was ablaze with videos and images of their luxurious wedding, at Çırağan Palace, a five-star hotel; President Erdoğan attended. The party was a particular affront to the Turkish people, who are enduring one of the worst economic crises in almost 20 years.

Upon taking over as publishers, the Demirören family didn’t develop any evident sense of what owning a prestigious newspaper required. Rather than invest in journalism, the Demirörens balked. A reporter who worked for the family said that they didn’t seem to understand why money was needed for anything. “They were constantly like, ‘Why do you need money for travel? Why do you need to go on a reporting trip? Why do we need such a big office?’ ” the reporter recalled. As another journalist, Esra Arsan, has written of Erdoğan Demirören, “Maybe he thinks that selling newspapers is like selling bottled gas. Fill them and sell them. When they get empty, just refill them, sell them, and line your own pockets.”

By 2011, Erdoğan and his AKP had conquered Turkey’s government, its military, its judiciary, its police, and its intelligence agencies. The country’s business leaders learned that, for their corporations to survive, they would have to abide by Erdoğan’s desires. Through corrupt legal proceedings, the administration began attacking secularists and journalists, especially those who Erdoğan believed had slighted him in the past. Opposition writers lost their jobs and went to jail.

At Radikal, for example, which was still owned by Doğan and where Murat Yetkin was still Ankara bureau chief, journalists found that they could no longer get anyone in the government on the phone—their sources had dried up. Pressure came not only from Erdoğan’s administration, but also from its allies in an Islamic movement called Gülen, whose members often terrorized liberal reporters. A new editor came to Radikal; Yetkin claims that he received pushback on one of his columns because it was critical of the government. Then Yetkin quit. “I left Radikal in 2011 because I could no longer do my job,” he said. Radikal would suffer many more personnel losses until it was eventually shut down entirely, the first of Doğan’s three most important papers to close in the Erdoğan era.

But it was what happened to Milliyet that marked one of the most dramatic devolutions in Turkey’s media. Sazak, who became the editor in chief of Milliyet in 2012, has said that early on, Prime Minister Erdoğan told him that he would never complain about news that was correct—he would only stand against an attack on his family. “We had a good start,” Sazak writes in his memoir, Down with This Journalism! (2014). He recalls that, soon after he was hired, he met with Erdoğan Demirören, who said of the prime minister: “I don’t want any problems. My wife and I are close friends with Beyefendi and his wife, and I don’t want to ruin our relationship.” (Beyefendi is an honorific that Turks use in formal situations, and which has become shorthand for Erdoğan.)

The Kingmaker: Turkey’s press was never free, but under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, journalists find it virtually impossible to do their work. Photo: Murad Sezer / Reuters Pictures.

The problems Demirören feared began soon after. In early 2013, Milliyet published an article with the headline “İmralı Zabıtları,” or “İmralı Minutes.” İmralı is the island that serves as the personal prison of Abdullah Öcalan, the founder of the PKK, a Kurdish militant group. The article featured notes from a meeting between Öcalan and several delegates from a more moderate Kurdish group in which they discussed the terms of a cease-fire between the Turkish government and the PKK. It was a great scoop. But the government felt that any impression of granting concessions to terrorists would not only threaten the peace process with the PKK, but also sour support for the AKP among Turkey’s nationalists. The morning the story was published, Sazak received a call from Yalçın Akdoğan, an Erdoğan adviser, who accused Sazak of trying to sabotage peace.

Then Sazak spoke to Erdoğan Demirören. “Why did you put up that headline?” Demirören asked. “Who leaked it?”

“There wasn’t a leak,” Sazak explained. “It was Namık Durukan’s reporting. He’s been following the Kurdish problem for years. A parliamentary delegation went to İmralı, and he returned with these notes.” Sazak sensed that the government was also harassing Demirören about the article directly. “If they are asking you about it, just say, ‘I have no idea, the editor in chief published it!’ ” Which was true. Up to that point, Milliyet was maintaining some editorial independence.

Soon, Demirören came to Milliyet’s office. Prime Minister Erdoğan had just denounced the “İmralı Minutes” article during a live broadcast. “This is the first time in my life that I have ever cried because of the news,” Demirören told Sazak. “I also believe this is journalism, but if only you had asked me first.” He looked ill. Sazak, struck with concern for Demirören’s health, called someone close to the prime minister and begged them to back off.

Later, Sazak would learn why Demirören seemed so devastated during their meeting. The following year, tapes of Demirören’s phone conversation with Erdoğan were leaked to the public by the Gülen movement—the AKP’s former allies, with whom Erdoğan had a falling-out. (The following version is abridged.)

Demirören: “Did I upset you, patron?” (Patron means boss.)

Erdoğan: “Well, you really messed up.”

Demirören: “We need to find out who leaked this.”

Erdoğan: “Who leaked it to you is a separate matter from whether it’s your newspaper’s job to do such provocations.”

Demirören: “Such a thing would never occur to us, my dear prime minister.”

Erdoğan: “If a headline can be put up like this, it doesn’t matter what occurred to you.”

Demirören: “Can I ask of you to give me a half hour?”

Erdoğan: “Well, I’ve put aside many half hours for you, ya? This is rude. After all this, actually, I’m not going to take one more man from your newspaper on my overseas trips. . . .How many times did I sit and talk to them? I talked to Derya [Sazak], too; my friends also talked to him. I mean, we were entering a good period, a peace process, we were taking risks. . . and over there they put up that headline. That unethical, vile jerk, he wants to sabotage our peace process. And you’re his boss.”

Demirören: “Okay, what do you want from me?”

Erdoğan: “Do whatever you have to do. You have to say to these dishonorable people, how could you put up this headline?”

Demirören: “I’ll do what I have to do, my prime minister.”

Before they hung up, Demirören could be heard weeping. Under his breath, he wondered aloud, “How did I get into this business?”

A wave of purges from Milliyet soon followed. Sazak writes that Demirören would tell him, “Don’t let this one write, send this one away, fire that one.” Employees who jumped or were thrown overboard would include luminaries of Turkish journalism: Hasan Cemal, Can Dündar, and Aslı Aydıntaşbaş.

Erdoğan, through the Demirörens, began demanding hires, too. Meltem Demirören asked Sazak to bring in a well-known Erdoğan ally, a journalist named Nagehan Alçı—the Hannity to Erdoğan’s Trump. The conversation went like this:

Sazak: “Why are you insisting on this so much? Who wants her?”

Meltem Demirören: “My brother [Yıldırım] promised.”

Sazak: “Promised who?”

Demirören: “Beyefendi.”

Just as Turkish media was feeling a tighter grip, protests broke out in Gezi Park, in the center of Istanbul. Having begun in opposition to the park’s imminent destruction, the demonstrations quickly became a nationwide revolt against police violence and declining democratic norms. Although Erdoğan was popularly elected, his reign was coming to be seen as increasingly authoritarian, as if the democratic inroads made during his early years were slipping away. Among the grievances of the protesters was that, while the park was being demolished, other parts of Istanbul were being rebuilt—including an unsightly shopping mall in a historic neighborhood that had been developed by, and named for, the Demirören family, suddenly visible cronies of the prime minister.

The protests terrified Erdoğan. Demirören called Sazak and forbade him from attending the protests, whether as a journalist or a citizen. Sazak went anyway. Demirören called him and said, angrily, “You lied to me.” Soon after, Erdoğan’s spokespeople and advisers began complaining that Sazak never consulted them. The Demirörens started asking not only why Milliyet editors used certain headlines but also why they didn’t choose others. Erdoğan’s advisers began requesting to see articles ahead of publication.

The more the Erdoğan government called on Demirören, the more Demirören began to mimic the government. In 2015, he summoned into his office Kadri Gürsel, an esteemed journalist. He told Gürsel that, in the run-up to the next election, he must “keep his writerly ego in check” or not write at all. “Your name came up three times during my meetings in Ankara,” Demirören said, referring to audiences with Erdoğan or his advisers. “And I still haven’t done anything to you.” It was, of course, a threat.

Gürsel, who had been in media for 30 years, would later write, “The most devastating conversation I ever had was the hour and a half I spent with Erdoğan Demirören.” In I’m Sorry for You Too (2018), the memoir in which he recounted their conversation, he also noted that Demirören had told him that he had never in his life read a book.

A few months after the conversation, Gürsel was fired from Milliyet. He would eventually spend 11 months in jail for his work at another newspaper, Cumhuriyet, and in May he was sent back to prison, along with six colleagues, on charges of “supporting terrorism.”

In March 2018, almost 25 years after he bought it, Aydın Doğan was finally forced to sell Hürriyet, his flagship paper, to the reluctant repositories of Turkish journalism, the Demirören family. He sold them CNN Türk, Posta, and Kanal D, too—in essence, the rest of the Doğan Media Group—for $1.1 billion. “Doğan concluded that doing journalism had become impossible in Turkey,” a reporter who worked with him told me.

Three months later, at the age of 79, Erdoğan Demirören died. His children now run the family media enterprise, led by Yıldırım, 54, a large man who inherited his father’s blocky face. According to Esra Arsan, the final transfer of control from Doğan means that 21 of the 29 newspapers in Turkey “are now in the hands of bosses that are closely allied to the government.” She adds, “Seventy-three percent of the country’s newspapers are now in the control of the AKP. Pro-government newspapers in the country now make up 90 percent of the national circulation.”

Murat Yetkin spent six months at the Hürriyet Daily News under the Demirörens before he saw the paper succumb to the same fate as Radikal and Milliyet. Under the Demirörens, newspapers couldn’t offer decent coverage of corruption, Kurds, Erdoğan family members, or religion. Reporters couldn’t say that an economic crisis would get worse or misstep on descriptions of July 15, the day of an unsuccessful military coup against Erdoğan’s regime. Yetkin began to self-censor in odd ways. Instead of delivering a short, sharp declarative—“He killed a man!”—he would temper his tone—“Oh, by the way, he killed a man”—as if nothing happened.

The only remaining Turkish outlet that appeared to enjoy any semblance of independence, aside from a handful of tiny leftist or nationalist papers, was, oddly enough, Fox News Turkey.

“It was the opposite of what political spokespeople do,” Yetkin explained. “They pretend they are saying a lot of things and say nothing. I pretended I said nothing even when I was saying something. Not only the Demirörens but almost all media owners have long abandoned taking on any subject they think would make the government unhappy.”

The week I met Yetkin for tea, it seemed like every day brought a fresh resignation or mass firing at Demirören outlets. As journalists departed, they often went with a goodbye tweet or a column that implied unhappiness with the situation at Demirören papers. In March, Faruk Bildirici left Hürriyet after 27 years, writing in his final piece, “I always wanted journalism to win. It may not today, but it definitely will tomorrow.” The only remaining Turkish news outlet that appeared to enjoy any semblance of independence, aside from a handful of tiny leftist or nationalist papers, was, oddly enough, Fox News Turkey, which had been left somewhat untouched because it was owned by a foreign company.

Few people in Turkey trust its media now; even some government supporters appear to share this wariness. Recently, I sat next to a well-educated Turkish man, a self-described leftist, on a Turkish Airlines flight, on which attendants were distributing Turkish newspapers. He picked up Milliyet and thumbed through it lazily. “Do you believe anything you read in that?” I asked. He laughed and said, “Of course not.” Another day, I saw a pro-AKP shop owner shake his head at a TV mounted above him. The channel was tuned to A Haber, one of the government’s network mouthpieces. “You sit here and you watch A Haber and you’d think we live in Norway,” the shopkeeper said. “Nope, no problems here whatsoever! Meanwhile, I can’t afford bananas.”

Yalçın Karatepe, a professor of finance at Ankara University, one of Turkey’s most prestigious institutions, told me that 10 years ago, he used to start his day with five newspapers. Now he reads none, and instead checks Resmi Gazete—the official bulletin of the Turkish government, which simply announces the laws and decrees passed in Parliament that day. “It’s the only thing you need to read,” he said, “because it tells you how, every day, they are passing laws to completely transform the country.”

Turkey’s press was never free. It was crusading and censored, vibrant and complicit, ideological and defiant. “In the nineties, very few people would say the military was burning villages, but people talked about the Kurdish issue,” said Aydıntaşbaş, the former Milliyet writer, now a fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. “It would be more like, What should we do? This is no way to treat people, it’s causing people to join the PKK. There was a debate.” Aydıntaşbaş recounted the story of Ahmet Altan, who wrote a column in Milliyet in the nineties called “Atakurd,” a riff on Atatürk, the name of the founder of Turkey—an almost unimaginably provocative concept at the time. “And he was put on trial, and eventually laid off,” she said. “But no one thought he would go to jail for something like that. Today there is no Milliyet of the nineties, and no one would even hire a man like Ahmet Altan. He wouldn’t exist.” As of now, Ahmet Altan has been in jail for nearly three years.

Whereas before there were multiple media players, today there is one, under Erdoğan’s power. “Today, there is no interest in seeking news,” Aydıntaşbaş said. “Now the newspapers don’t even cover the opposition parties, or even Parliament.”

Worse, the media that has replaced the working press is viciously, often bizarrely in sync with the government’s suppression of dissent. A synergy exists between the media and state prosecutors. If a newspaper designates an academic or a journalist or a political figure as a threat, very often an indictment against that person will follow and he or she will go to trial, or to jail. In particular, Cem Küçük—a pro-Erdoğan journalist who works at Türkiye (not a Demirören paper)—is a terrifying figure. Anytime he predicts in one of his columns that a reporter will be fired, that firing soon takes place. His columns are the AccuWeather of political oppression.

The destruction of Turkish media has come full circle. Where journalists once sought to expose what the government was up to, now they act at its behest to expose—even to help prosecute—their common “opposition.” These days, if an independent journalist dares to write anything controversial, whether on social media or, say, to a foreign reporter like myself who then publishes the quotes abroad, they will wait out the next 24 hours with trepidation, praying that Twitter trolls or Cem Küçük will not have chosen to make their statement the hysterical target of the day. Why would anyone risk saying anything at all, let alone reporting?

In December, while reflecting on protests in France, Fatih Portakal, a beloved Fox News broadcaster, said on air that he wondered if peaceful demonstrations could happen in Turkey anymore: “How many would go on the streets with all this fear and anxiety? Tell me, for the love of God, how many would take that risk?” He was just asking questions, as journalists do. But in the repressive, sycophantic Demirören era, questions can seem to the government like provocations. The next day, at a rally, Erdoğan accused Portakal of trying to incite a revolt. Screaming into a microphone before thousands of fans, Erdoğan said of Portakal, “If you do not know your place, this nation will hit you in the back of your neck.”

Suzy Hansen is a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, and the author of Notes on a Foreign Country: An American Abroad in a Post-American World (2017). She lives in Istanbul.