From the very start of his political career, journalists have been conflicted over how to cover Donald Trump. From Margaret Sullivan of The Washington Post declaring, “The Media Didn’t Want to Believe Trump Could Win, So They Looked the Other Way” to Nicholas Kristof’s mea culpa in the pages of The New York Times (“My Shared Shame: The Media Helped Make Trump”), journalists have struggled with their role in the election that brought Trump to the White House. And now, as his presidency unfolds, they are still trying to find their footing.

Data from Harvard’s Shorenstein Center show that Donald Trump received significantly more coverage than Hillary Clinton across the campaign. Yet, at the same time, in a practically perfect illustration of what’s been called “false equivalency,” the tone of coverage of each candidate’s fitness for office was precisely equal—and highly negative—despite one candidate being demonstrably more experienced and qualified than the other.

This imbalanced “balance” likely sprang from the press’s perception—finely honed by multiple polls—that Clinton was the presumptive winner. Indeed, many reporters have told us privately and some have said publicly that the press’s underlying standard for reporting on the two candidates was different—and that for candidate Trump, the bar was lower. As Dan Morain, editorial page editor at the Sacramento Bee, says, “Trump wasn’t held to the same standard as a guy running for lieutenant governor of California.”*

ICYMI: He was excited to profile a controversial athlete. What happens next? Every journalist’s nightmare.

But those different standards were based on more than simply most journalists’ bet that they would soon be covering a Clinton rather than a Trump White House. Deeper than poll-driven election forecasting was the fundamental frame established around Trump’s candidacy. Because Trump entered the presidential stage from the world of business hucksterism and reality TV, he was seen, from the outset, as a less serious contender. In fact, he was treated as a joke.

During the campaign, Salena Zito noted on The Atlantic’s website that “ . . . the press takes [Trump] literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally.” We think this is more than a tweet-worthy truism. Precisely because Trump is so unconventional, the standard rules and mores for covering presidential politics are a poor match. It is because Trump flouted presidential conventions that the establishment press dismissed his candidacy. And they didn’t take him seriously as someone who could be president until it was, essentially, too late.

While it’s tough to make this argument with hard data, we devised some ways to glimpse what we have come to call the Trump Conundrum as it played out across the campaign.

We gathered all stories—those that appeared in print as well as only online—from two leading outlets, The New York Times and The Washington Post, across 11 key moments in the campaign (for each moment, capturing stories for two days after the event in question): Trump’s campaign launch (June 16, 2015); the first GOP debate, when Trump sparred with Fox News host Megyn Kelly (August 6, 2015); Trump’s call for a Muslim ban (December 7, 2015); Trump’s loss in the Iowa caucuses (February 1, 2016); so-called Super Tuesday II, at which point Marco Rubio left the race (March 15, 2016); the exit of Ted Cruz and John Kasich (May 3-4, 2016); Trump reaching the delegate threshold (May 26, 2016); the reaction to Trump’s attack on the parents of slain US soldier Humayun Khan (August 1, 2016); the first debate between Trump and Hillary Clinton (September 26, 2016); the release of the infamous Access Hollywood “hot mic” tape (October 7, 2016); and FBI Director James Comey’s letter to Congress announcing additional investigation into Hillary Clinton’s emails (October 28, 2016).

This came to a total of 1,518 news stories, blog posts, and opinion pieces. Although online posts comprised 70 percent of all the articles, the findings are strikingly similar for print and non-print posts, with no major substantive differences.

We found that overall coverage of Trump increased over the course of the campaign, peaking after the first presidential debate in September 2016. We then coded each story to track a number of indicators, including its overall tone: Did the story generally cast Trump in a positive, negative, or neutral light? According to the data, coverage of Trump was rarely positive and, at most points in the campaign, predominantly negative rather than neutral.

So, on the one hand, Trump and his supporters were right: The media were generally negative toward Trump. But negative how? We wanted to further probe the coverage to understand precisely how Trump and his campaign were described.

Because Trump entered the presidential stage from the world of business hucksterism and reality TV, he was seen, from the outset, as a less serious contender. In fact, he was treated as a joke.

We found, first of all, that Trump’s unconventional background received relatively prominent coverage early in the campaign, but references to his business and entertainment résumé fell off as the campaign wore on, just as voters were headed to the polls. For example, mentions of Trump’s background in entertainment appeared in 40 percent of stories when his candidacy was first announced, but then dropped off sharply. We also found that Trump’s personal attributes were covered much more negatively than positively, contributing to the overall tone of the coverage. While early in the race Trump won some favorable descriptions as a straight-shooter, depictions of him as a truth-bender became increasingly frequent as Election Day neared, and negative descriptions of his personal character outnumbered positive ones by about six to one overall.

Coverage of Trump’s more polarizing statements and attitudes was also a fairly consistent feature of the coverage. News about Trump’s racist and xenophobic statements spiked most notably in early December 2015, when the candidate called for a ban on Muslims entering the US, and in early August 2016, when he attacked the Khan family, whose son died in Iraq. And Trump’s attitudes toward women received heavy coverage in conjunction with the first GOP debate in August 2015 and, not surprisingly, again in October 2016 when the infamous Access Hollywood tape became public.

Even more revealing, we think, is how these outlets covered Trump’s electoral chances. It’s not surprising that as Trump prevailed in Super Tuesday contests in March and his Republican rivals Ted Cruz and John Kasich left the race in May, positive coverage of Trump’s chances increased. But our data show that even as Trump passed the delegate threshold in late May, coverage of his chances became significantly less positive—presumably as the press looked ahead toward the general election. By the time Trump attacked the Kahn family during the Democratic convention, the press’s assessment of his electoral viability tanked, not recovering until the release of the Comey letter a week before Election Day gave Trump a surprise late-game advantage—and then only barely surpassing coverage that portrayed his chances negatively.

This is a critical point: The data paint a picture of a press that only came to terms with the idea that Trump would become the Republican nominee when that fate was all but sealed, and that never came to terms with the idea that Trump could actually become president. Because, we think, they didn’t take Trump seriously.

In order to test this key idea, we coded each story for two mutually exclusive variables. First, the “serious” variable was used for articles that gave reasoned consideration to Trump and his campaign with substantive discussion of the potential benefits or dangers of a Trump presidency. Overall, 18 percent of the stories were “serious” by this definition. Second, the “clown” variable was used for articles that made fun of Trump, usually using dismissive, even snarky descriptors. In these pieces (16 percent of the articles in our data), Trump was described as “brash,” “flamboyant,” a “celebrity bomb-thrower and provocateur,” a “doughy showman,” a “bombastic reality TV star” whose “distinctive vernacular (‘yuge,’ ‘loser’) and physical features (hair swoop, suspicious tan) practically write their own jokes.”

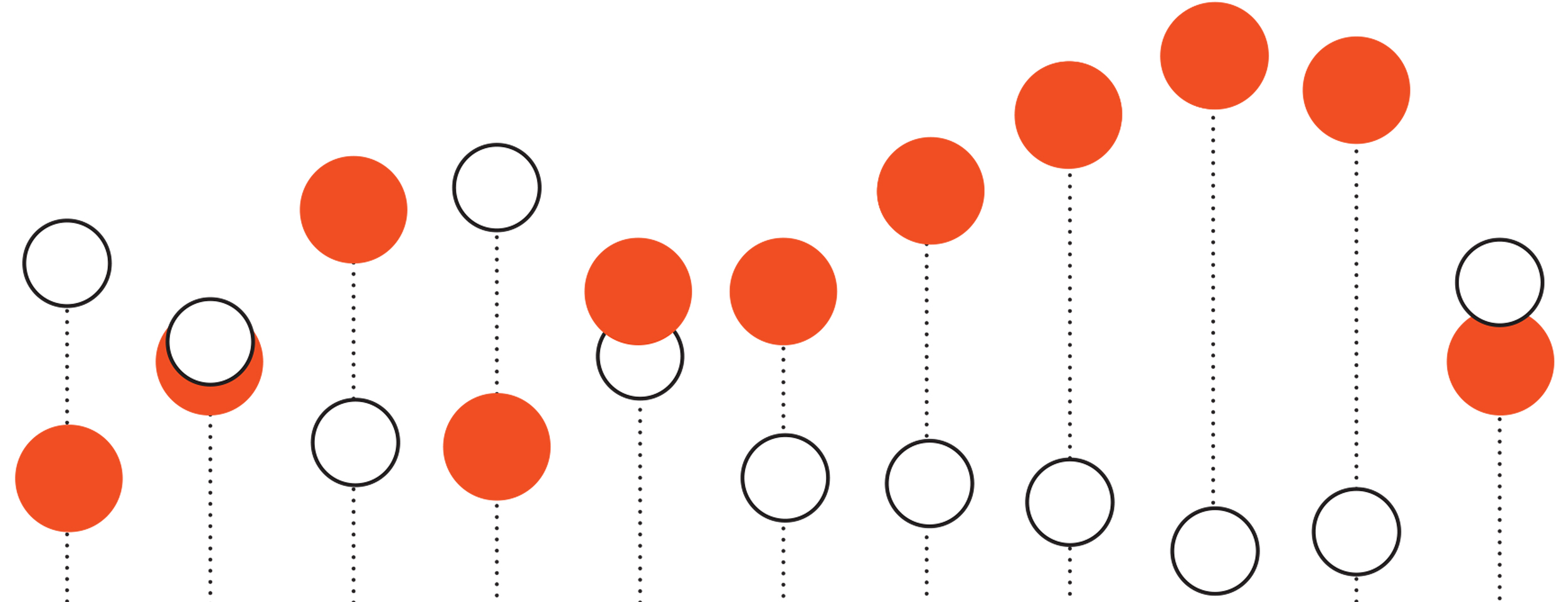

Tallying Trump’s press New York Times and Washington Post stories about Trump following key campaign moments. Click on image to view at a larger size. (Graphics by Cynthia Hoffman)

One date to consider is May 26, 2016, when Trump passed the GOP delegate threshold and became the presumptive Republican nominee. It is at precisely this moment we might have expected—and wanted—the press to take Trump seriously. Such coverage had increased previously, when Cruz and Kasich exited the race. At that point, journalists started to engage more earnestly with the substance of Trump’s appeal to voters (e.g., “Trump is filling a vacuum left by years of inattention to voters who have been patronized and taken for granted”) and casting him both as a political contender (e.g., “it would be a mistake to underestimate Trump or presume he cannot win in November”) and as a threat to be taken seriously (e.g., “As much as his neo-isolationism frightens our allies, it is Mr. Trump’s anti-establishment stance that most threatens international security”; “Donald Trump is an urgent threat to our rights and to our country”). But by the time Trump became the presumptive nominee, the “clown” coverage was again more dominant, with stories that were more caustic or dismissive, saying things like “So much for the speculation that Trump’s team is competent,” and detailing Trump’s appearance on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, including the host’s reference to Trump as a “tangerine-tinted Godzilla.” And again in coverage of the first debate between Trump and Clinton, Trump was treated more like a circus act than our potential next president.

ICYMI: “I spent 45 minutes on the phone with Megyn Kelly asking her to not run that show”

The “clown” cues and “serious” cues seesawed across the course of the campaign. The divergence between serious coverage that examined Trump’s policy proposals and the kind of president he might be versus dismissive portrayals of The Donald suggests the establishment press simply could not reconcile its cognitive dissonance—not only about whether Trump might win but also about the very premise of the question. Throughout the campaign, the press never figured out how to portray the sheer unbelievability of Trump’s quest for the White House.

While colorful descriptions of Trump were good for a laugh (and for news outlets’ readership metrics), this dismissive frame points to a serious blind spot. Standard journalistic and political norms left the press struggling to conceive of Trump as someone who might one day sit in the Oval Office, so unshakable was the conceptualization of him as a clown. In this way, Trump’s entertainment persona served as a Trojan horse as Trump smuggled himself into the very real world of presidential politics. The US has seen its share of celebrities-turned-politicians. But while previous celebrities have traded on their fame and their comfort in front of the cameras, they more or less became politicians over time. Trump never made that turn. And the press simply wasn’t equipped to cover a presidential campaign fueled by entertainment aesthetics.

Running underneath, through, and beyond these gaps between normal politics and Trump politics, is the Trump Conundrum: How should the press cover a showman who turns out to be deadly serious—and who refuses to play by the rules of the long-running game of presidential press politics? Alec MacGillis of ProPublica got it right when he observed, “What the press wasn’t able to do, and what it was almost not set up to do, was to get across the sheer ridiculousness or surreality of Donald Trump running for president.” What the press did do was consistently portray Trump as a non-serious candidate, all the way to his win on Election Day.

In short, Trump’s genesis and skills as an entertainer (as well as a business-world huckster and a demagogue) played into mainstream media vulnerabilities and blind spots in ways that benefitted Trump’s bid for the presidency and left the media scrambling to get a fix on him. And here is the point: This struggle is entirely understandable.

Now that they cannot dismiss him, the mainstream press must figure out how to grapple with Trump in a serious way. The puzzlement is palpable in interviews we conducted in the spring of 2017. A veteran national newspaper reporter described to us the slow process of realizing Trump could “get away” with saying things that other politicians would not:

It was apparent pretty early that the rules had changed . . . . I’d call it in August 2015, the first Republican debate, and then when Trump went after Rosie O’Donnell and then made those comments about Megyn Kelly and we all shook our head and said, ‘Oh, that’s it, he’s done.’ Because in the past, I mean, my goodness, somebody made a statement like that, that was it. Plus, he didn’t have any party backing, he wasn’t an insider, and yet he not only survived, but he thrived. And a few weeks later, Carly Fiorina got in trouble because she claimed to have seen the allegedly pulled fetus or something, remember that, and boy that was the end of it for Carly Fiorina. So we figured, oh, well Trump’s going down, too, and he didn’t. There was always this element of surprise about his campaign. The rules didn’t matter. And that continued right on up to the end.

As Morain of the Sacramento Bee, told us:

Once it became apparent that he was a serious candidate and had a serious chance to win then people started taking him more seriously, but [the mainstream press] didn’t take him seriously initially. We were having conversations in 2015 with one of my colleagues here and I just shook my head and said, ‘There’s no way this guy is going to win.’ I viewed it as a joke campaign. I’m not unique. Many, many people who have been around politics, who have covered politics for a long time did not view him as serious. The joke was all on us, right? We were just flat wrong . . . . the voters didn’t really seem to mind that he didn’t understand the nuances of NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Our data validate Morain’s observations and also call into question the notion that the press took Trump more seriously as the campaign progressed. It’s now clear that the Trump Conundrum urgently needs the press’s serious and thoughtful attention. Because Trump is not a unique phenomenon but, rather, an example of the type of entertainer/politician hybrid that we might expect to see more of in the future. With his mastery of reality TV drama and accrued experience as a frequent talk-show guest in venues from Fox News to Letterman and Kimmel, Trump has blazed a pathway right through the establishment press’s normal standards for presidential behavior. As Susan Milligan, senior writer for US News & World Report, told us, “I think that he opens the door for other nontraditional candidates, no question about it.”

How, then, should the press cover Trump (and future Trumps)? At a minimum, Trump’s unexpected electoral success should raise awareness of the slippery slope running from entertainment to politics. Candidate Trump more or less built his campaign on his ability to generate controversy and thus news—an arrangement that benefitted many in the media as well, as expressed vividly in the reported comments of CBS’s president and CEO Les Moonves at an investor conference, saying that the Trump campaign “may not be good for America,” but “it is damn good for CBS . . . . The money’s rolling in and this is fun . . . . Bring it on, Donald. Keep going.”’ As political consultant Doug Elmets put it when we interviewed him, “Donald Trump understood something that none of the other candidates did. Maybe even news media didn’t fully understand. That is how to manipulate the message. Saying the most outrageous things for the full purpose of capturing and then managing the news cycle.” And that success explains the “balance” Trump achieved with Clinton: beating her at the quantitative news game while diffusing focus on his own questionable qualifications.

But beneath the Trump-is-good-for-the-bottom-line problem lies another, deeper one: Today’s watchdog journalists need to treat entertainment not as a sideshow but as a powerful vehicle for real political messaging. Belittling an entertainment-fueled candidate no longer works to communicate the serious threats he or she poses. Journalists need to account for the fact that, in the age of comedy news (Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee, John Oliver), just because we laugh at entertaining figures doesn’t mean we won’t take their messages to heart. And in the age of the anti-hero, from Tony Soprano to Breaking Bad’s Walter White, just because we are repulsed by entertaining figures doesn’t mean we won’t vote for them.

*Additional reporting by Peter Van Aelst, who assisted Boydstun in interviewing journalists.

ICYMI: The first reporter to arrive at Vegas gunman’s house has covered the story in many ways–except one

Regina G. Lawrence and Amber E. Boydstun are the authors of this story. Regina G. Lawrence is a professor in the School of Journalism and Communication and executive director of the George S. Turnbull Portland Center and the Agora Journalism Center at the University of Oregon. Amber E. Boydstun is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science and a Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of California, Davis