In early 1998, Tom Junod received an assignment that was outside his wheelhouse. His editor at Esquire asked him to profile Fred Rogers, the beloved television personality and Presbyterian minister. By the time Junod was done writing the story, he had become friends with Rogers. The two remained close until Rogers’s death, in early 2003.

Junod and Rogers exchanged dozens of emails that would reshape Junod’s religious faith and, as a result, his approach to journalism. The beginning of their friendship inspired A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, the recent movie starring Tom Hanks as Rogers and Matthew Rhys as a journalist based on Junod.

This past summer, the movie’s screenwriters shared with Junod the contents of a file that Rogers had kept throughout their friendship. In it was a piece of paper on which Rogers had jotted four precepts for journalism:

Journalists are human beings not automatons. Human beings not stenographers.

Journalists have a duty to let their outrage show through when they come across injustice.

Journalists need to let their compassion show through for other people’s suffering.

Journalists need to let their ahhh (wonder) show through when they witness the glory of life… they have as much responsibility to celebrate life and the goodness of it as they do to root out evil.

CJR spoke with Junod about those principles, how his friendship with Rogers changed the way he approaches journalism, and how that relationship came to bear on his faith. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

It caught me completely by surprise. I was amazed by it. We certainly don’t think of Fred Rogers as a professor at J-school.

What was going on in your life at the time you began the story about him?

Right before I met Fred, I wrote two stories for Esquire that really chewed me up. One was about Kevin Spacey, in which we outed him and did a rhetorical dance around that. Kevin, in response, called for a Hollywood boycott against me and the magazine. The other thing I wrote was about a person in the Atlanta area, a twin who had killed his twin brother. The mother called me after that story came out and basically said, “How could you do this? How could you do this for a magazine story?” It’s one of the things I’ll never forget. Not just How could you do it? but How could you do it for something as inessential as a magazine story? To me, a magazine story was not inessential. You would walk through fire to write a magazine story.

With [my editor] David Granger, our philosophy was: Show the thing that you’re writing about. If you’re writing about a crime, go into the crime. I thought that I could only do that for so long. I was going pretty deep into the tank.

When I first met Fred, I knew that he was different from anybody else I’d ever met. And the thing that sustained me through the reporting and writing has turned out to be what has sustained me through my career since then: it has been this possibility that goodness might be as interesting as evil. Ever since I was quite young, I was mystified by the existence of human evil. But Fred offered me a completely different avenue of inquiry. I look at my career as “before Fred” and “after Fred.”

In the Esquire piece about Fred, you wrote, “There was an energy to him, however, a fearlessness, an unashamed insistence on intimacy, and though I tried to ask him questions about himself, he always turned the questions back on me.” That must have been jarring for a journalist.

It’s not just jarring for a journalist. Generally when you meet people, they’re more interested in answering questions than they are in asking them. It was extraordinary on a couple of levels. It was extraordinary to have the questions turned on me, but it was also extraordinary just to hear somebody express interest in me in that insistent a way.

It was definitely the kind of thing where I understood that I was going to have to make a decision. Am I going to battle, or am I going to go for this particular ride? I decided to go on the ride. That was a conscious decision: He is turning this around on me; can I, in turn, turn that around on him by making that the bones of the story? Which is essentially what I did.

How did your relationship with Fred evolve from “journalist and interview subject” to friends?

I think that Fred was extremely talented at friendship. It was a remarkable ability he had to form bonds with people. He had that. But I think that he saw that I needed to be trusted again, and he gave me that. That was the great gift he gave me. He trusted me. And I think he trusted me because he saw the need in me.

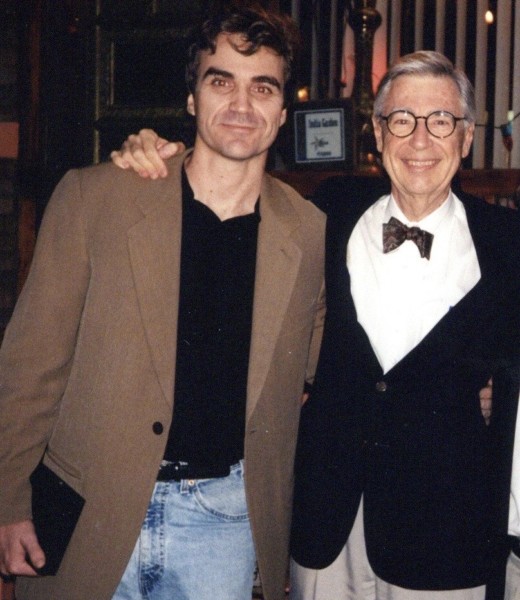

Junod, left, with Rogers. Courtesy of Tom Junod.

His emails were just so extraordinary. I would send him long emails with lots of questions about good and evil, God and the absence thereof, and he would write these long answers back. And over the course of four years there were seventy of these things.

Fred made me think about: Is God good? Does God love us? Is love the basis of creation?

Fred’s answer to all three was a resounding yes, and he lived by that answer.

I was not so certain and am not so certain now. But Fred made me realize that if love can be at the center of human interactions—and there’s no doubt it can be, because he proved it—then the possibility that there’s not only a moral arc to the universe, but a loving one, is not as far-fetched.

What was your own faith background? Were you raised religious?

I went to twelve years of Catholic school, and that experience does not just dissipate. It sticks with you. I definitely stopped being a practicing Catholic, but Catholicism has always been a part of me.

Fred showed me a lot of different things about religious practice. He definitely figured out a secular language for spiritual matters. That whole “you are special” thing—I look back on it now and it’s very much a religious sentiment that he managed to couch in not just secular but childlike tropes.

Also, Fred was very Protestant. He was a Presbyterian minister. His relationship with God required no intermediaries. Fred’s prayer was very direct.

Was there something about that that spoke to you in a different way than your Catholic upbringing had?

Oh, yes. It was definitely, like, my own personal reformation. I think Fred turned me into a Protestant. My daughter was baptized at a Presbyterian church. That was in 2004, after Fred died. And one of the lingering regrets of my friendship with Fred is that he did not get to meet my daughter.

When I met Fred I did not have a child, and I would say our [my and my wife’s] childlessness at the time was an issue. It was definitely something I was really, really angry about in my life. I was angry at God, to be quite open. Fred was the person who softened some of that for me, for sure.

How did this softening affect your journalism? In the four precepts he wrote down, Fred stresses the importance of celebrating goodness. What does that mean for us?

The thing that’s really interesting about that particular sheet of paper is that I learned about it this summer. And it caught me completely by surprise. I was amazed by it. We certainly don’t think of Fred Rogers as a professor at J-school. I don’t know whether this was something Fred was trying to communicate to me, or maybe it was something I communicated to Fred. I don’t know.

I’ve been working on a story for ESPN for a while now, for a year and a half, about a tragedy that happened on the ball field and all the people who were affected by it. There was a crime in it, a crime that was unveiled by this tragedy, and a secret. And when I started doing this story, nobody would really talk to me. I had that familiar feeling as a journalist: I want to do this story, I need to do this story, I’m gonna do this story, but man I feel shitty being the villain here. And I think that’s a fairly familiar journalistic emotion. But I kept at it. Recently, I got a call from one of the people in the story, and he wanted to apologize to this person who had been looking for an apology for this thing for a really long time. And so I helped facilitate this thing, and it was so extraordinary. I just realized the opportunity that journalists have when they tell people’s stories, and how important and sacred those stories are to the people who are sharing them with you. And did I think of Fred Rogers and his precepts? I did, very much so.

Stephanie Russell-Kraft is a Brooklyn-based freelance reporter covering the intersections of religion, culture, law, and gender. She has written for the New Republic, The Atlantic, Religion & Politics, and Religion Dispatches and is a regular contributing reporter for Bloomberg Law. Follow her on Twitter: @srussellkraft.