In September 2018, Tiffany Ferguson, a twenty-five-year-old college student and YouTube personality with more than six hundred thousand subscribers, sat down in her bedroom, ready to record. She wore a navy-and-red turtleneck sweater; her blond hair was tied into messy braids. Typically, she used her channel for in-depth “story times” detailing random events from her day. But on this occasion, she told subscribers, her video would be different. “I have a little bit of something to say about the YouTube algorithm and the role of rapidly rising creators,” she said. Ferguson then launched into a thirteen-minute meditation on internet fame, algorithmic bias, and the importance of relatability to an influencer’s success. She reported information gleaned from Social Blade, a social media analytics tracker, and offered her interpretation of the facts. “That’s my two cents: thoughts on the YouTube algorithm and seventeen-year-olds that I can still relate to,” Ferguson said. “I’m not that old.” The video was an instant hit (it now has more than four hundred thousand views) and inspired her to change direction. She launched a new series, “Internet Analysis,” in which she discusses all things politics and culture: “girlboss” feminism, reality television, internet virality. Each installment has attracted more than a hundred thousand fans.

Ferguson is one of many stars on “commentary YouTube,” also known as LeftTube. In some cases, the creators, as they’re known, address a wide range of topics. Other channels are niche: “Ask a Mortician” talks about death, mortality, and the funeral home business; D’Angelo Wallace gives his take on intra-YouTube drama; “Ready to Glare” covers Twitter policies, cults, and mental health. Not every video is tied to the news cycle, but commentary YouTube will ground the subject at hand in relevant cultural and political analysis. There’s a disquisition on “cancel culture,” an explainer on Marxism, a diagnosis of the controversy surrounding the film Cuties. That last post received more than two million views.

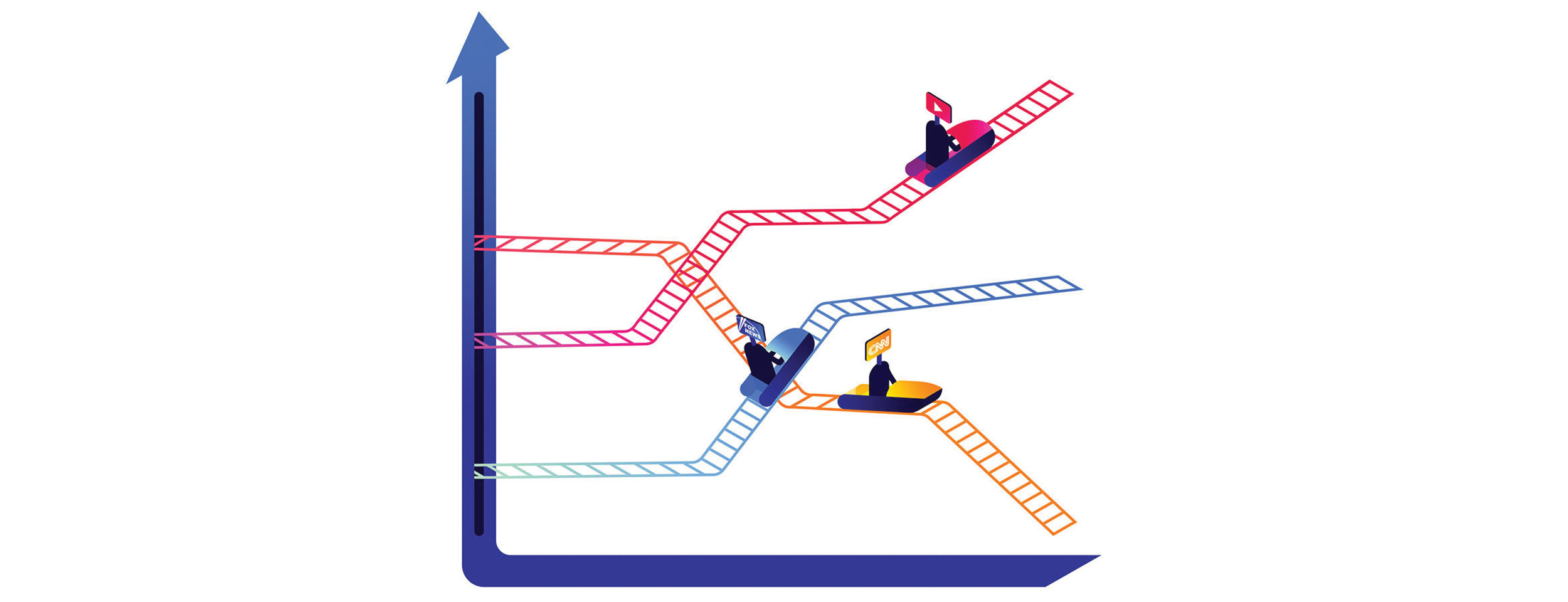

It’s no wonder these videos are popular; most Americans now prefer to watch rather than read their news. And, according to a recent study from the Pew Research Center, 26 percent of adults get their news from YouTube, with the majority of that cohort saying that the platform represents an important means by which they stay informed.

Individuals with large followings and the time to devote to research are seizing the opportunity to challenge the dominance of mainstream outlets. It’s a young crowd: the creators and audience members in the commentary-YouTube orbit are typically no older than thirty. Ferguson normally spends about a week preparing before she sits down to record; in the final cut, she comes across as effortlessly approachable. “I don’t want to shy away from politics—I think my videos come from a leftist perspective, but I’m not as overt in making political commentary in every video,” she told me. “Because my channel is more accessible, people who maybe aren’t as engaged with news or politics can get inspired by my videos to do more research on these topics because I’m using more casual language and style.”

For written articles, freelance journalists make, on average, around twenty cents per word. Depending on the number of ads and other factors, a twenty-five-minute YouTube video that garners a hundred and fifty thousand views might deliver its creator $580; for three million views, the sum may be closer to $6,800. Kimberly Foster, the thirty-one-year-old behind a YouTube channel called “For Harriet,” told me that, as her audience swelled, she quit contributing to publications like The Guardian and HuffPost to focus on her LeftTube career. “I get to be much freer and use colloquialisms,” she said. “When I was writing, I felt more like ‘Stuffy Kim.’ But when I’m just talking to the camera, it’s more like ‘Free Kim’—I know how I’m going to present topics and what facial expressions I’m going to use when I say certain things. I know I can approach political topics with rigor but still be accessible.”

“For Harriet” videos include a historical look at how enslaved women’s bodies contributed to modern gynecology and discussions of colorism and prison abolition from a Black feminist perspective; Foster also posted a review of the movie version of Cats, from 2019. (“I want to be fair,” she joked to viewers. “I want to make sure everybody gets the blame that they deserve.”) Her analysis is of a kind that’s largely lacking on YouTube; in June, Black contributors filed a racism lawsuit, alleging that the company systematically removed their videos without explanation. (“Our automated systems are not designed to identify the race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation of our creators or viewers,” a YouTube spokesperson said at the time; it’s also true that algorithms are often racist.) Speaking one’s mind can be tricky, given the opacity of YouTube’s monetization system, in which creators may not be paid for overtly leftist material. The result, especially for Black YouTubers, can often be financial insecurity.

But Foster has found alternative ways to fund her work. “I never wanted to be in the position where a social media platform changes the algorithm and does not allow me to make an income,” she told me. “So around the time that websites like The Atlantic and the New York Times started relying more on digital subscriptions, I knew I would need to start relying on my audience in the same way.” A few years ago, she started a Patreon. “It’s honestly changed the game for me,” Foster said. She has more than thirty-three hundred patrons, who pay between $2 and $50 per month for extra videos and podcasts—it’s a steady living. Other creators have done the same, with even more impressive results: “ContraPoints,” focusing on leftist politics and LGBTQ stories, has more than twelve thousand backers on Patreon who contribute between $2 and $20 per month. “Now I don’t care if YouTube demonetizes my videos,” Foster told me. “I can make whatever content I want without censoring myself.”

Most Americans now prefer to watch rather than read their news.

User-funded video channels seem like an exciting premise: direct support of your favorite YouTube star. But it’s an intense relationship, and one that complicates the dynamic between commentator and news consumer: you’re not subscribing for vetted journalism; what you get are hot takes. David Craig, a clinical associate professor of communication at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School, told me that watching commentary YouTube can distort viewers’ perception of information: “You could argue that on YouTube, it’s less about what’s being said and more how it’s being said.” Loyalties develop, and opinions harden.

For YouTubers who fund their videos through Patreon, there’s an added incentive to keep viewers happy—and they might feel inclined to target their coverage to fans’ tastes. The echo chamber includes other media, too: YouTubers also function as influencers, carrying their followings to Instagram and Twitter, where they promote themselves and engage with audience members. Critical distance is impossible—and intentionally unwelcome.

“I think the appeal of commentary YouTube is being able to find a personality you like, maybe someone you would want to be friends with, and then be able to listen to them geek out about stuff you find interesting and can learn from,” Ferguson told me. The stars of commentary YouTube are part role model, part journalist, part friend—they help you keep up with the news in a way that’s easily understandable and fun.

Void of that old-fashioned newspapery pretext of objectivity, commentary YouTube caters to a young audience whose members, well acquainted with the spoils of the internet, are seeking human connection. Their favorite videos can become their primary means of engagement with the news. “I’m definitely drawn to the personality of the YouTubers I watch, in addition to their content,” Yasemin Losee, a twenty-two-year-old graduate student and avid viewer of channels like “Ready to Glare” and “ContraPoints,” told me. “I look for creators who share similar morals to mine or who I could engage with on an intellectual level—and it also doesn’t hurt if we even have the same aesthetic.”

Mary Retta writes about politics and culture. Her work can be found in New York magazine, The Atlantic, The Nation, and elsewhere.