Fox News is authoritarian state media. Fox News is the only truthful outlet. Fox News is Tucker Carlson. Fox News is Chris Wallace. Fox News is thriving. Fox News is dying. Fox News is the real America. Fox News sells miracle cures and identity-theft protection to a small number of unhappy old people.

Understanding America’s most popular cable news channel has come to feel even more urgent in the run-up to the presidential election. If Trump refuses to accept unfavorable returns on November 3 and in the days thereafter, he will count on Fox to play along—potentially sowing weeks, or even months, of resistance and protests. And although the channel’s news programming has some independence, however strained, from the opinion division, which oversees Carlson, Sean Hannity, and others, it was the news desk that seemed defiant on election night in 2012, when Megyn Kelly left her anchor’s chair to berate her own analysts for calling Ohio for Barack Obama.

Americans tend to watch Fox News either religiously or never at all. For the latter camp—like me, until recently—understanding the channel is one way to comprehend an America that has come to seem distant to those of us who could never have imagined a Trump presidency. And to that end, it’s worth considering Steve Doocy.

Unless you are a regular Fox viewer, you may only remember Doocy from The Daily Show’s Moment of Zen—a brief excerpt of television that the producers find somewhere else in TV land, played alongside the closing credits. It’s a few seconds of self-evident absurdity, a bit of TV that is funny even, or especially, shorn of context. Calculating, nefarious, ideological evil makes for bad Moment of Zen material: Hannity and Mitch McConnell do not work well. But Doocy, who since 1998 has been a host on the Fox & Friends morning show, was a regular.

The Moment of Zen from January 12, 2010, is a fourteen-second clip of Doocy talking to his cohosts about the influence of late-night comedy. “When William Jefferson Clinton was running for president,” Doocy says, sitting on the sofa next to then-cohosts Gretchen Carlson and Brian Kilmeade, “a lot of people say that what really got a lot of juice for him was the fact that he went on The Arsenio Hall Show…” The clip then cuts to Doocy barking Hall’s signature “Woof! Woof!” Doocy doing an Arsenio imitation—that’s the punch line.

Ten years later, it’s not as easy to laugh at Doocy. He is watched daily by the president of the United States, whose rise Doocy goosed with regular invitations to Fox & Friends back when the idea of Trump as president was a punch line. Fox & Friends helped make President Trump—and now helps make President Trump’s agenda. According to a Media Matters study, between September 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020, Trump sent 1,206 live-tweets about television shows, nearly all of them Fox programs, and 355 of them in response to something he was watching on Fox & Friends.

And many of those segments represent a brand of casual fear and divisiveness that pervades Fox News and has washed over much of America in the past four years. For Fox & Friends viewers, there is an immigrant invasion, populated by criminals, murderers, the other. After the Trump administration began separating families at the border, Kilmeade emphasized that these are “not our kids.” Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib are communist and anti-American, as is, according to some guests, wearing masks to prevent the spread of covid-19 . On Fox & Friends, a lighthearted segment can feature a QAnon supporter wearing a brick-wall outfit to a Trump rally.

To many, Doocy is a faux simpleton at the head of the vast right-wing machinery, somebody who toggles between reciting the president’s talking points and writing them, in an endless, mindless morning-TV loop. But this past summer, as I spent many covid -quarantine mornings with Doocy and his cohosts on their famous “curvy couch,” I realized he is no puppet master. Nor is he a simpleton. He is something else.

Doocy lacks the rage of his cohost Kilmeade, who has all of Hannity’s spittle but even less engagement with ideas, and he shows none of the deer-in-headlights vacancy of Ainsley Earhardt. He is, rather, precisely somebody for whom Bill Clinton is a footnote to Arsenio Hall. In a Doocy world, pop-culture levity rises above the news, is above the news.

Doociness gets to an important and little-understood part of Fox News: like Doocy, most Americans are not zealots like Hannity or Tucker Carlson, or perpetually enraged like Kilmeade. According to two political scientists who study political engagement, 80 to 85 percent of Americans “follow politics casually or not at all.” And yet millions of them voted for an insult comedian whose political philosophy, to the extent he has one, is “Lock her up!” There is a little bit of Doocy in all of them.

Courtesy of Steve Doocy

Stephen James Doocy—Stephen to his parents but Steve to his four younger sisters and his subordinates in the Future Farmers of America, which he served as chapter president at Clay Center High School in 1974—was born in 1956 in Algona, Iowa.

His father, Jim, worked at Welp, a huge chicken hatchery, in the town of Bancroft. Welp was the company in a company town, and numerous Doocys had drawn Welp paychecks over the years. When Steve was young, his dad took a new job, selling advertisements for a plat book, an atlas showing who owns what in a rural area. He was given Kansas as his territory, and the Doocys moved to a town there called Russell, where Jim Doocy would sometimes bump into a young congressman, Bob Dole, running errands. “They would talk about things people talked about in the sixties,” Doocy said, in one of four lengthy phone calls I had with him as summer turned to fall this year. “ ‘Hey, Jim, how about that Bay of Pigs?’ ”

Jim soon took a new job, and the family bounced around, doing time in Abilene and Salina. In sixth grade, Doocy attended a one-room schoolhouse in Industry, where the last post office closed in 1906. There were eleven students, four of them Doocys.

As a teenager, Doocy liked Kurt Vonnegut, whose countercultural celebrity was peaking at the precise moment Doocy was feathering his hair for his first junior high dance. He had played with the idea of becoming a doctor, but now, as an aspiring wordsmith, he developed a strong vocational crush on the two young reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, breaking story after story about Richard Nixon’s malfeasance. “As the nation was caught up in Watergate, it’s like, ‘How come it’s only these two guys who are figuring out the whole story? That’s so cool!’ ” Nixon resigned in August 1974, the month before Doocy began his senior year of high school.

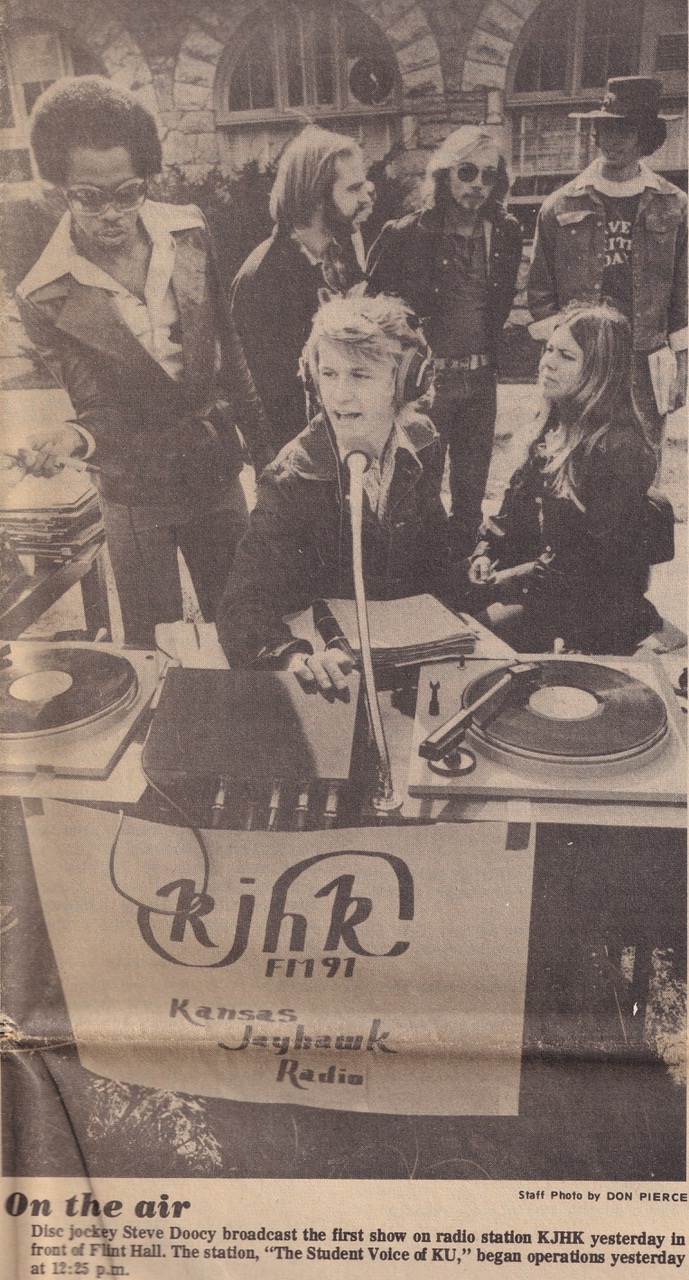

Doocy worked on his school newspaper, and the next year he was off to the University of Kansas to study journalism. On the first day of school, he and his roommate, a fellow Future Farmer of America, were walking around campus when they heard loud music “coming out of a little scroungy-looking building. And the door was open, and we walked in. And we walked directly into the control room of a radio station. It was a hot day, and the door was open because the AC didn’t work.”

Doocy had never given a thought to college radio, but he liked the idea. As a teenager, one of his other great heroes, besides Woodward and Bernstein, was Paul Harvey, a radio host and erstwhile McCarthyite beloved by millions, although not by the liberals he red-baited (according to a New York Times obituary in 2009, Harvey also “railed against welfare cheats and defended the death penalty. He worried about the national debt, big government, bureaucrats who lacked common sense, permissive parents, leftist radicals and America succumbing to moral decay. He championed rugged individualism, love of God and country, and the fundamental decency of ordinary people”). Doocy had no opinion of Harvey’s politics; he just loved a good storyteller.

Musically speaking, Doocy’s tastes had always run to the lite end of contemporary—Jim Croce, James Taylor, Elton John—but now, as a DJ, he pushed the boat out from shore a bit. “You would just say, ‘Those were the Moody Blues, and next up, here’s Boz Scaggs!’ ” On October 15 of his freshman year, Doocy was behind the turntable when word came that KJHK had gotten FCC permission to broadcast beyond the campus, to a radius of almost ten miles. As the new signal went live, Doocy chose the first song, Jimi Hendrix’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

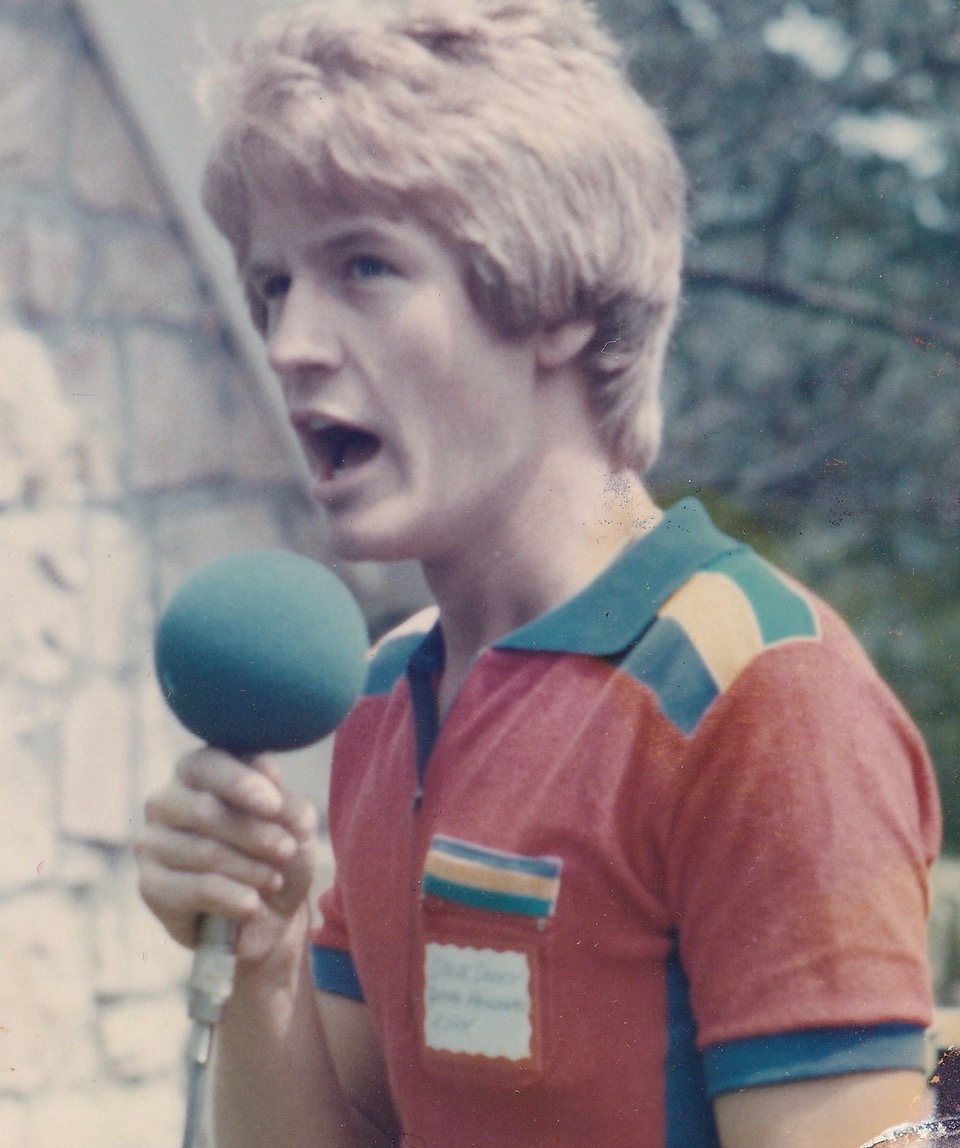

In small-town Kansas, KJHK was the place: DJs scored interviews with Blondie, Tom Petty, Patti Smith. And Doocy did stints as program director and station manager. He became KJHK. He was the perfect man for his time and place: pumped for an interview with the Ramones, but uninterested in drugs or revolution. (He never smoked pot, although he did enjoy 3.2 beer, which was for sale in grocery stores at a time when much of Kansas was still dry.)

Courtesy of Steve Doocy

He still revered Woodward and Bernstein, but man, radio was fun. And television, too, which he would soon discover suited him just as well. Doocy had it: the right mix of ego and affability to enter other people’s living rooms and put them at ease. His junior year, he took a part-time job at the NBC affiliate in Topeka, doing news and weekend weather. That summer, 1978, he lived in a house near campus with a radio-station pal named Gary Lieberman. Lieberman is now a freelance video editor in Atlanta, and a liberal. I asked him if he was surprised to see Doocy working for right-wing Fox.

After thinking it over for a few seconds, Lieberman said, “I’ll go on the record as saying yes. Yes, it has been weird.” Had Doocy always been the conservative in their group? “No, not at all,” he said. “I will say just the opposite.” He told me that Doocy was the friend who helped him be okay with gay people—they had a mutual friend who was out of the closet—before that was the thing to do. (Doocy had no idea whom Lieberman was referring to, but he seemed charmed by the story.)

Mainly, Lieberman remembered Doocy as a worker. He said Doocy carried a pad of unlined yellow paper wherever he went. “One day, I walked into his room at our house, and I looked down, and there on the paper was scribbled some joke I had said, or some clever thing I had said, and I realized there were pieces of paper all over the room like this. He collected things he found funny on these yellow sheets of paper, to be a resource for material down the road.”

Courtesy of Steve Doocy

If one had to describe the politics of Steve Doocy on the eve of his college graduation, in 1979—the late Carter years, inflation high, six months before hostages were taken in Iran—one might say he was a good-government solutionist liberal. He was against corruption, was untroubled by the loosening cultural mores of the Me Decade, and shared the broad American optimism that government could be a force for good.

“Everybody in the Doocy family was a Democrat,” Doocy said. When he was still at home, his mother had begun to develop heart troubles. “And while my dad had jobs, we never had health insurance. I don’t know that I knew anybody with medical coverage.” His high school girlfriend, whose parents were leaders of the Democratic Party in Clay County, got him involved in the congressional campaign of Bill Roy, a pro-choice congressman running for Senate in 1974 against Dole, now a powerful incumbent Republican. Roy, a doctor, was pushing for universal coverage. “And look, I wanted to protect my mom,” Doocy said. “I was like, ‘Look, that’s the best thing anybody has ever come up with. I have to pull out all the stops.’ So I knocked on doors for Bill Roy. Ultimately, he lost. And that was heartbreaking.”

In 1984, he left Kansas for a plum job with WRC, the NBC affiliate in Washington, DC. He specialized in goofball segments, branded “Steve Doocy’s World,” that ran at the end of the news half hour. In a late-eighties segment that survives on YouTube, Doocy interviews Bob Golub, a New Yorker who believes that his potatoes, regular spuds on which he writes his name in black marker, bring people luck. As Golub ambles around DC, trying to bestow potatoes on people, he is followed by Doocy, who asks viewers, “Why is he so a-peeling?”

Doocy got offered a daily syndicated show, House Party, based on the long-running Art Linkletter show of the same name. The show, which taped in NBC’s Studio 8H at Rockefeller Center, home of Saturday Night Live, lasted just one season. After that, Doocy bounced back to Washington, but not for long. He had caught the attention of television producer and political consultant Roger Ailes—the messaging genius who had worked with Nixon, Reagan, and the first President Bush—whom NBC had hired to start a new twenty-four-hour news channel called America’s Talking.

The main premise of America’s Talking, which went on air July 4, 1994, and lasted two years, seemed to be, “We can do twenty-four-hour talk that’s way less serious, and way more fun, than what they’re doing on CNN”—the big cable news network of the time. It launched the television career of Chris Matthews, who had a nighttime politics show. The middle of the day featured shows like Am I Nuts?, with Long Island psychologist Dr. Bernie Katz and behavioral therapist Cynthia Richmond solving people’s problems, and Bugged!, a show about stuff that bugged people. And in the morning, from seven to nine, America’s Talking, with Doocy and his cohost Kai Kim. The hosts chatted and cooked and bantered with Tony Morelli, “the Prodigy Guy.” Morelli worked for early internet service Prodigy, which had a partnership with the network; viewers were invited to post their feedback on Prodigy for Morelli to share, in an early version of the Twitter real-time feedback loop. Morelli did his bits while sitting in a classic American convertible, “the Prodigy Vehicle,” in front of a screen, with highway scenery going by—to show that he was on “the information superhighway.”

America’s Talking was shut down in 1996, after NBC decided to partner with Microsoft to form MSNBC. Doocy’s colleagues from that period emphasize that they had no idea if he was a conservative. What they remembered was that he and his wife, Kathy, were generous hosts who would have everyone out to their place in Wyckoff, New Jersey. Bill McCuddy got hired at the network by winning a nationwide search for a new host, a publicity stunt Ailes had cooked up. Doocy was there when McCuddy was introduced. “We were taking this group picture,” McCuddy remembered, “and he leaned down to me and said, ‘Never work with puppets.’ ”

After America’s Talking was shuttered, Ailes jumped from NBC to News Corp, where Rupert Murdoch hired him to start the right-leaning network that would be Fox News Channel. Ailes took a bunch of his America’s Talking talent with him, including Katz, Mike Jerrick, McCuddy, and Doocy. At first Doocy was doing the weather—a reprise of his first role in Topeka local news—but almost immediately he was made one of three cohosts of Fox & Friends, the job he has had ever since.

When it launched, in 1998, Fox & Friends hewed pretty close to the immensely lucrative morning-show model, pioneered by Today on NBC and Good Morning America on ABC: regular news breaks punctuating long stretches of “lifestyle” segments, about animals or cooking or celebrities. But not for long. “It really all changed with 9/11,” Doocy said.

The show didn’t drop the lighter fare entirely, but at a moment when the country went all in for patriotism—when the Dixie Chicks (now just The Chicks) could mortally wound their own career by criticizing the president from the concert stage—Fox stood out for its jingoistic fervor. Fighting terror, supporting the troops, and attacking dissenters became the Fox brand. It was great for ratings.

Even the lighter fare became more political, a change most evident in the role of Donald Trump. When Fox & Friends began featuring the future president, he was very much a lifestyle guest—socialite, real estate developer, reality TV host, People magazine cover boy, one-man brand. Then, in 2011, he began using his Fox appearances to promote his obsessive “birther” crusade, trumpeting the baseless theory that Barack Obama was not born in the United States (a theory in which Fox hosts like Hannity also dabbled). On March 28, 2011, as Trump was on the phone with Fox & Friends talking about Libya, the network ran a graphic asking, “What would President Trump do?”

Doocy has never seemed as intense about politics as his cohost Kilmeade, who appears as though he needs to fan himself whenever Trump joins the show by phone. Nevertheless, Doocy has been the genial ringmaster for almost twenty years of on-air immigrant-baiting, gun-rights salivating, white-nationalist coddling, and Obama-hatred. He has been the chief attendant to Trump; when he has given pushback, asked tough questions, it’s only to the point that Trump enjoys, so the big man can mix it up.

At one point, frustrated, I let Doocy have it. I said that my liberal friends and I look at the president and think of his “pussy grabbing,” his lies, his refusal to release his tax returns, his attacks on China and immigrants—all of it—and wonder how a decent person could vote for the man. Even if one agrees with his conservative policies, it would have to be a tough vote to cast. No? “It seems not to touch you,” I said.

Doocy conceded the point, sort of. “That is an excellent question you pose, and I honestly hadn’t really thought about it like that…”

Doocy says he voted for Trump in 2016. He once voted for Jimmy Carter, and he used to be an independent, but he is now a registered Republican—so he can vote in primaries, he told me. “I voted for Ross Perot either one or two times, because it’s like, whatever was going on was not working. I didn’t like either party. I think most of my adult life I have been more in the middle, and then, when given the choice between the two, it’s What policies I am most concerned about right now? To be honest, since 9/11, for me, the big stuff is security—national security, personal security.”

What about the other stuff?

Doocy on gay marriage: “Absolutely. I have a couple family members who are gay, and I would love for them to get married.”

Doocy on Joe Biden: “I have always found him to be a nice guy. Would he be a great president? If that’s what America says, that’s what America says. I can’t think of any time I have said to myself, ‘Man, we’re stuck with a terrible president.’ I have liked all of our presidents. They are out to make America the best it can be.”

Doocy on Barack Obama: “I liked a lot of Obama. Before he ran for president, then-Senator Obama had one of his books come out, and he stopped by Fox & Friends.… I was in the greenroom with him for, like, fifteen or twenty minutes. We had a very nice conversation.”

Doocy on assault rifles: “I will tell you what a police chief said to me when we went to a gun range. He said—and I am on his side on this—‘There’s no reason the average person should have that gun. Because if they have that gun, and I have that gun, I have no advantage.’… I think the cops need bigger guns than the bad guys.”

Doocy on immigration: “I think it would be better if people signed the guest book on the way in.… We need to find something different.… Let me think about that.”

Doocy on climate change: “I am of the opinion that the globe is getting warmer, and it’s hard for me to believe that man does not have some sort of impact on that.”

Doocy on abortion: “I think abortion should be so rare—it can’t be outlawed, because there are circumstances where women need abortions. But I feel it’s a life, and that makes it very complicated.”

Doocy on the death penalty: “I’m not a big death penalty guy. I’d rather see somebody, if they did something pretty terrible, stay in prison their whole lives. But if you kill a cop? Does it rise to that level? The president says yes.… I don’t know if I’ve made that distinction yet.”

Doocy has written four books: Tales from the Dad Side: Misadventures in Fatherhood; The Mr. & Mrs. Happy Handbook: Everything I Know About Love and Marriage (with corrections by Mrs. Doocy); and two cookbooks with his wife, Kathy, the second of which, The Happy in a Hurry Cookbook: 100-Plus Fast and Easy New Recipes That Taste Like Home, was published last month and debuted at number one on Amazon’s best-seller list.

As he has aged, Doocy has moved back toward his Catholic faith. He attends Mass regularly, and he often talks about religion during his daily walks with Tony de Nicola, his close friend and a devout Catholic who has given millions to the University of Notre Dame. The shift began with the death of his mother, JoAnne, on Christmas Day, 1997. For over a year, he had trouble sleeping. Until, one night, Doocy dreamt that his phone was ringing, and when he answered, his mother was on the line. She was fine, she said, and she was able to watch Fox & Friends in heaven. Then he woke up—sad that it was a dream, but cheered nonetheless. Then, a few months later, before falling asleep, he looked through the skylight at the moon and asked God for a sign. “Let me know,” he implored his creator, “there is a second act.” He addressed his mother: “Mom, if you’re up there, somewhere—show me.”

When his alarm went off, at 3:27am, Z-100 FM, New York City’s Top 40 powerhouse, began to play a particular tune. “I was about to turn off the clock radio when Janet Jackson started her hit song, ‘Together Again,’ about how one day she’d be reunited in heaven with a lost loved one,” he writes in his new cookbook. “I listened to the whole song with goosebumps the size of saucers. That was some impressive signage, I thought, and I felt a wave of something good wash over me.”

Today, Steve Doocy is sixty-four, he’s made his money, and he doesn’t have to keep hitting the alarm clock at 3:27 in the morning. But he was born to be on the air, and he is. That’s a privilege, and Doocy is a grateful man. But I wonder if, like the rest of us on the downslope of life, he ponders whether he picked the right mountain.

One former America’s Talking producer compared Doocy to another radio personality who landed in right-wing media. “I feel like Steve Doocy is like Glenn Beck, a journeyman DJ who will do what you need,” the producer said. “ ‘You want me to do country? I’ll do country! You want me to do AOR?’ ”—album-oriented rock—“ ‘I’ll do AOR.’ Then he stumbled into right-wing [TV] and was kind of good at it. He was the ambling guy who would bop around the office being goofy. To see him transformed into this guy has been weird.”

When we spoke in September, Doocy said he was still an undecided voter. “I’ve got to see,” he said. Doocy told me he wished people could just talk to one another again, and really listen. He said he could imagine voting for Republicans and Democrats in the future. I asked which Democrats out there might win his vote. “I will tell you this,” he said. “I went to a Pete Buttigieg rally in New Hampshire, and I liked his message a lot. And Kevin Costner was there, and I did a little interview with him, and it’s like, I think he’s interesting.” (I think he meant Buttigieg, not Costner.)

Then, in October, a month after I first asked Doocy whom he was voting for, I checked in with him again. By this time, there had been one debate and the dueling town halls on the night of the canceled second debate. America was, at that moment, perhaps the most polarized it has been outside of wartime. Doocy was not too concerned.

“I am going to tell you a story,” Doocy said. “Election night, 2016, what time did you go to bed?” About midnight, I told him. “I went to bed at 9:15,” he said. “Because what are you going to do? I knew who I had voted for.” The next morning, he learned of Trump’s victory from a note left by one of his children. “I was like, Wha? But I was not so invested in any of the candidates that I had to see what happened. I got a good night’s sleep.”

Mark Oppenheimer is the author of Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood, to be published next year. He hosts the podcast Unorthodox for Tablet magazine.