Matt Saincome was used to ignoring people. In 2014, he and his friend Bill Conway cofounded The Hard Times, a satirical website often described as a hardcore version of The Onion, and ever since they had been shooing away potential buyers. There were Hollywood types who wanted to turn The Hard Times into a BuzzFeed-like YouTube channel, tech companies that hoped to optimize the ads, larger magazines that offered to remake the site as a comedy show. For almost six years Saincome, a former music editor at SF Weekly and the more business-savvy of the two, listened to every proposal and rejected all of them. So far, he and Conway had been self-reliant, with no outside funding; they weren’t looking to sell. And that was an accomplishment. Especially when you consider that their scrappy enterprise had survived the media industry’s most tumultuous time—as hedge funds and private equity firms became notorious for buying up suffering local newspapers and digital properties, then stripping them for parts. Saincome likes to say The Hard Times was “born in the shit”; a more pleasant image is that it was nimble and slim, relying on a stable of paid freelancers who believed in the vision. Layoffs, pivots to video, Hulk Hogan: Saincome and Conway didn’t have to deal with any of that. They had the luxury of not being in financial trouble.

Saincome’s thinking hadn’t changed last October, when a stranger cornered him during a Hard Times book launch at Saint Vitus, a metal bar in Brooklyn. It was yet another guy saying that his company—some firm created by Wall Street shakers—was keen on buying The Hard Times. As usual, Saincome agreed to chat. He figured he had nothing to lose from hearing the man out.

By May, The Hard Times had been sold to Enrique Abeyta, a former hedge fund manager, who acquired the site through Project M Group, his digital media and e-commerce company. Founded in 2017, Project M is helmed by Abeyta, who serves as the CEO, and Skip Williamson—a financial strategist turned independent record label executive and Hollywood producer, whose title is chief creative officer. “These guys quit Wall Street,” Saincome told me. “They’re huge metalheads.” The name Project M is an in-joke, an allusion to the fact that investment bankers don’t label their projects what they actually are, fearing that documents might leak into the market. The M might stand for metal, media, monetization. Abeyta won’t say. “If you want to paint Enrique as a guy who is investing in publications and not harming them, that’s a hundred percent correct,” Saincome said. “He really is more similar to me than you would expect.”

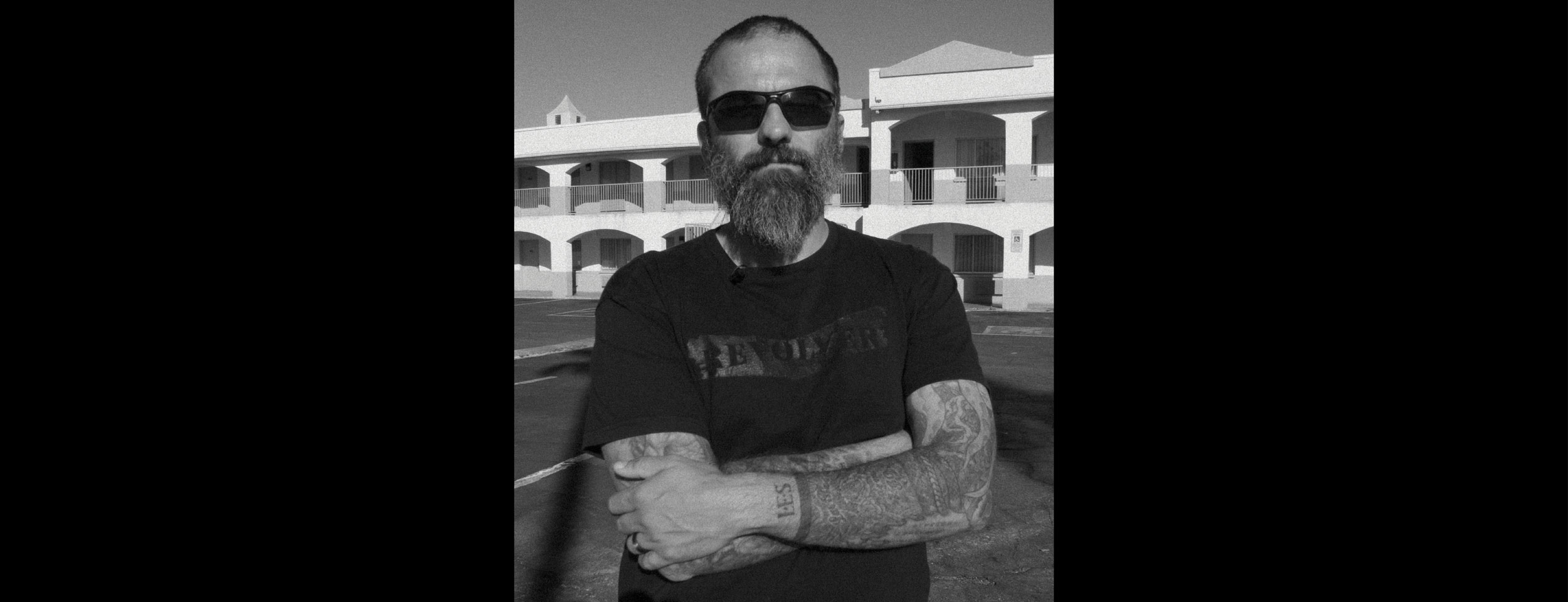

A self-made millionaire and second-generation immigrant with tattoos on the side of his head, a mangy beard, and unkempt hair that resembles a mohawk, Abeyta, who is forty-eight, jokes that he looks like a pirate. He has seen the band Tool in concert at least forty times. His buddies call him Rick. When we met, he wanted to show me he isn’t like any other hedge-funder I may have come across. He rattled on with the assured vulgarity of a Guy Ritchie character—“fucking Yelp,” “fucking tattoos,” “the fucking Yankees”—and at times sounded like a slam poet. His favorite metaphors involve the ocean: he rode the nineties hedge fund wave, saw the tide of local news “going out in front of a tsunami,” showed his employees how to surf the startup waters. He does not do well with silences; he is constantly about to say one last thing. “People like goblins and ghouls and witches and gods,” he told me. Then he added, “Everybody wants a bad guy.” He doesn’t believe he is one.

It was only a few years ago that Abeyta put on a tie for work. At the end of his hedge fund days, he was a senior analyst at Falcon Edge, in Manhattan, earning seven figures. (The chairman, Rick Gerson, is a good friend of Jared Kushner’s and later became wrapped up in the Robert Mueller investigation.) Abeyta’s attention often wandered toward media properties and direct-to-consumer companies; in 2016, he closely followed the success of the Chernin Group, the investment advisory firm that bought a majority stake in Barstool Sports, and the CHIVE, a photo blog that slapped Bill Murray’s face onto T-shirts. Seeing vertical integration—of journalism and consumer goods—piqued Abeyta’s interest. So when a mutual friend introduced him to Williamson, and Williamson made him a proposition—a venture in publishing that would capitalize on the fan base of metalheads, their kin—it lured him. He’d already had years, he said, when he “made seven figures, lost seven figures, and made something in between”; he was accustomed to volatility and ready for the next thing. He abandoned his comfortable salary and invested what became $2 million in Project M.

Abeyta and Williamson set off with a mission: first, they would buy struggling or underperforming media companies with passionate, niche audiences with whom they identified; second, they would resurrect those companies with capital; third, they would sell merchandise to their enlarged reader base. Before The Hard Times, they acquired Revolver (heavy metal) and Inked (tattoos). “My life’s work has been to study strategy in media, as part of my investing,” Abeyta said. “I’ve always been a student of the game. At my last firm, they called me the master of the ‘Game of Thrones,’ because through time, I had a great ability to identify moves in the media space by thinking strategically.”

Abeyta was indeed different, though he fit a type: he reminded me of Bryan Goldberg, the founder of Bustle Digital Group, and Shane Smith, my old boss at Vice—bloviating men whose braggadocio could eclipse common sense. It’s considered prudent to be wary of those guys, yet by making Project M in his image, and insisting to editors that his hedge fund days are behind him, Abeyta has managed to sell people on his alt-finance-bro brand. “What we try to do as a great partner is, we say, ‘Here’s how you can own a stake in this, here’s how you can do more of what you love to do, and we can do all the crap that you don’t like to do and also put you in a position to do more cool shit,’ ” he said. It helps that Project M has managed to turn a profit. Saincome told me, “It seemed like a perfect fit.”

In late July, I drove north of Phoenix, past thousands of acres of untouched Sonoran desert, to a small town called Cave Creek, where Abeyta was living with his wife and children. He compared Cave Creek to Marin County, by which he meant that it’s far enough away from Phoenix (an increasingly liberal-leaning city) to maintain its own libertarian idiosyncrasies. Sometimes Cave Creek makes national news: in 2009, for instance, a judge decided the outcome of a tied council election with a deck of cards; this year, as Arizona became a hot spot for covid cases, the Wall Street Journal reported that a popular saloon in Cave Creek waited until the end of June to require masks. Abeyta asked me to have lunch at a Wild West–themed restaurant in town called the Horny Toad. After we sat down, and there was a brief lull in our conversation, he took out his George Costanza–size wallet and showed me a deposit slip: it was the first million in his bank account, he explained. He’d kept it for years, as a memento, the numbers faded from rubbing against credit cards. He continued on, narrating the story of how he amassed riches. A few times, I heard him say, “I made money on 9/11.”

Abeyta has always been driven by a desire to earn. His father, a Mexican American from New Mexico, was often out of work and suffered from alcoholism; his mother, born in Uruguay, left her homeland in the late sixties, a few years before a military dictatorship took over. They bounced around; as a child, Abeyta lived in Utah, Colorado, and Spain before settling in Phoenix. For a few nights, his parents couldn’t afford the motel where they were staying, and they were kicked out, homeless. They slept in the car. “Being poor sucked,” he said. “I wasn’t really anything except poor. I don’t really know that you get a chance to develop much of a personality in that situation.”

He did, anyway. He collected comic books; he played Dungeons and Dragons. He was gifted and popular, he told me, while maintaining a self-proclaimed “edge.” In high school, he was the freshman treasurer, the sophomore president, the junior president; his senior year, in 1990, he was the salutatorian and voted “most likely to succeed.” He interned in the office of Sen. John McCain. When it came time for college, what he wanted most was to learn the quickest, surest way to get rich. So he chose to attend the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, where he earned a BA in Asian and Middle Eastern Studies and a BS in economics. His friends were pedigreed; they liked chatting about stocks. He pledged a frat (Sigma Alpha Epsilon), signed up for investment management clubs, and rose to be the editor in chief of The Red and Blue, a conservative newspaper. He met a Jewish woman and adopted her religion. (He continues to pray.)

In 1993, Sponsors for Educational Opportunity, a nonprofit that helps young people from underserved communities land jobs, placed him in an internship at Lehman Brothers, which led to a full-time position. He started as a technology media telecom banker, then transferred to hedge funds. At the time, the World Wide Web was beginning to emerge, and hedge funds were booming—not only because of penny stock fraud, but also thanks to legal data gathering; smaller funds could make big money fast. Abeyta began at Atalanta Sosnoff, where he became fascinated by the consolidation of radio stations and newspapers. His boss had voting shares in the New York Times; Abeyta sat in on some meetings with the paper’s management, taking notes. Fox News debuted in 1996, and when the parent company, Fox Entertainment, went public, Abeyta, then in his mid-twenties, met Rupert Murdoch in a conference room at the World Financial Center. He was enamored. “Whatever you may think of men like Murdoch, he was an incredible business and value builder,” Abeyta said. “My views on journalism and media weren’t made up with me in front of a fucking screen, blogging.” Abeyta’s other idol is John Malone, the chairman of Liberty Media Corporation, which controls SiriusXM, among other holdings. Over the years, Abeyta told me, he invested between $2 billion and $3 billion of his clients’ money in Liberty Media, and flew out to Denver to meet with Malone. (Through a spokesperson, Murdoch declined to comment for this article; Malone’s flack did the same.) When I pressed Abeyta on what, specifically, he learned from these men, he compared himself vaguely to a line cook shadowing a great chef. “It’s a million things,” he said. He seemed to be overstating his proximity to his heroes, but in any case, a lesson stood out: both Murdoch and Malone had a knack for constructing “flywheel” businesses—grouping media assets together. They were rulers of kingdoms.

Abeyta came to view the stock market as “the most fascinating intellectual monetary competition in the history of humanity” and to pride himself on being “a great intellectual athlete.” In the aughts, he continued to play. In 2001, he built his own fund with a few partners; in late 2007, he cashed out and started another. He developed a reputation for being able to extract commitments from institutions and high rollers. (“He says that he’s a ‘make money’ investor—I loved that phrase,” Whitney Tilson, an ex–hedge fund manager who runs a newsletter service called Empire Financial Research, told me.) Abeyta was an active short seller. Then the Great Recession hit, in 2008, which marked the end for many newsrooms across the country, their demise accelerated by Abeyta’s colleagues.

In the past decade, hedge funds and private equity firms have colonized the media, as the main bidders for financially strapped local newspapers and digital properties that were now distressed assets. Abeyta observed two ways in which his cohort approached the press. First, there was slashing: buy a declining business with an assist from the bank, cut costs, and recoup more than originally invested. This has been a popular tactic at local newspapers, where reporters have lost their offices and careers by the thousands. (“Newspapers are dead,” Abeyta told me. “I hate to say what they’re doing was going to happen one way or the other.”) The most feared and despised predator in this category may be Heath Freeman, the president of Alden Global Capital—which owns or has a stake in some two hundred newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune and the Denver Post. In a major bid in August, Chatham Asset Management, an investment advisory company, won the bankruptcy sale of McClatchy and its dozens of local papers (the Miami Herald, the Sacramento Bee). It’s difficult to estimate just how much money these firms are making, but in 2017 Ken Doctor, a news industry analyst at Nieman Lab, reported that Alden was enjoying profits of almost $160 million from Digital First Media, just one of its assets.

The second move, Abeyta went on, was the “next-gen version,” or consolidation. “If I own ten newspapers, and all of them have an ad sales person, and all of them have a digital person, and all of them have somebody in logistics, I can ditch nine of those ten people and stick with the newspeople,” he said. “And you used to have twenty tenured reporters, and their”—the investors’—“belief is, ‘I can go find three college kids who are bloggers that can do the same thing.’ ” He gave as an example Maven, a digital-platform company that last June added Sports Illustrated to its roster of titles, which also included Maxim, Ski, and History. The new managers promptly laid off the most respected and best-paid staffers and later revealed that they would hire a few less experienced, lower-compensated replacements.

Abeyta wasn’t impressed by either strategy. “You’re still playing in the same revenue pool,” he told me. The media industry is brutal; advertising is no longer a reliable source of cash. “These hedge funds, they don’t know jack shit,” he said. “I was one of these guys, and I thought I was pretty smart about this. I had so much to learn.” In his view, the problem with Wall Street plundering the press hasn’t been the downfall of journalistic rigor and civic engagement, but that nobody’s earned enough money to make the effort worthwhile: “Those guys are picking up nickels in front of steamrollers.” The logical move, Abeyta said, if one is interested in media, is to “own” an audience, feeding them material they like to read along with stuff they want to buy. That is his way, and what became the basis of Project M.

In Abeyta’s view, the problem with Wall Street plundering the press hasn’t been the downfall of journalistic scrutiny, but that nobody’s earned enough money to make the effort worthwhile.

When Abeyta set his eyes on Revolver, in 2016, he sent an out-of-the-blue LinkedIn message to Brandon Geist, who had worked at Revolver for ten years and was now the editorial director of Rolling Stone’s website. Geist had been gone from Revolver only two years, and he wasn’t dying to return to what he called the “small and very complicated pond” of metal. Besides, Revolver was trending toward oblivion; at one point when Geist was in charge, his online budget was zero dollars. In meetings, he’d have to justify himself to the owners by explaining Slayer’s importance. But Geist was exhausted from the pace at Rolling Stone and told Abeyta that he’d be willing to talk. They got together near Geist’s office, in Midtown Manhattan. Abeyta showed up sweating in spandex; he’d biked there. “Initially, I’m like, ‘What the fuck?’ ” Geist said.

Abeyta detailed his vision for Revolver and Project M. “You could tell there was a lot of exciting energy coming off him,” Geist recalled. To conclude, Abeyta opened his laptop: “He showed me a spreadsheet of every concert he’s been to in his whole life, meticulously laid out. All these details were noted, and he told me his various rules about what counts as a show. It was really kind of amazing. It spoke to his personality, but also to his fandom.” After Abeyta bought Revolver, he tattooed the magazine’s logo, a single R, on his hand.

Geist was impressed by Abeyta’s devotion to heavy metal, but it’s also true that Abeyta is, more broadly, a fan of fandom. That’s the lens through which he regards media, as an array of outlets serving their fan bases; Revolver is to metalheads what Fox News is to Republicans. Abeyta is not a moralist and claims that he isn’t political; he only wants to cultivate a community of active consumers, united by their interest. In his acquisitions, he is bundling publications with similar audiences, centralizing what had been decentralized.

It took him some time to work out the particulars. For the first two years, Project M’s expenses were too high, and there was no money coming in. Abeyta and Edmund Sullivan, the chief financial officer, kept writing checks to stay afloat. During that period, Abeyta was also consumed with personal hardship: members of his family died at a rapid clip—his mom, his dad, his grandma. He packed up his apartment in New York and moved to Cave Creek.

Then Abeyta sought out Inked, which was thematically close to Revolver but came with robust merchandising capabilities. (You can decorate an entire house with stuff you’ve obtained on Inked’s website, like Day of the Dead–patterned plates, mystical shower curtains, and vampire-cat fleece blankets.) “We just didn’t have SKU numbers,” Sullivan said. “We didn’t have T-shirt manufacturers. And we didn’t have the audience to sell into.” After the deal closed, Abeyta estimated, 80 to 90 percent of Project M’s revenue started to come from e-commerce. With Revolver, Inked, and now The Hard Times, Abeyta is building a network in which each site’s products appear on the others’—one big store. “We haven’t quite optimized that yet,” he said. “We’re crushing it so much in merchandise.”

As an extra incentive to keep the business up, Project M offers its senior employees, including Geist and Saincome, partial ownership. “All my employees understand what our monetization is,” Abeyta told me. “I will also go, ‘Here are five stories: this is how much this will make us, and this is how much this will make us.’ Just so they know.” It’s the kind of conversation that typically signals disaster—a collapse of the wall between business and editorial. Producing coverage to maximize profit is just too tempting. When I spoke with Geist and Saincome, however, they didn’t seem all that concerned. Abeyta was hands-off, Saincome said; his involvement in The Hard Times was limited to stuff like suggesting which headlines could make for good T-shirt slogans. Geist’s tone suggested a sense of resignation. “I’ve always been told that I’m a very branded-content- and marketing-friendly editor,” he said. “There are some editors who draw very sharp lines, but I’m not like that.”

At the Horny Toad, Abeyta asked me why journalism existed: “Is it a public good, or are newspapers actually moneymaking enterprises?” He already had his answer. “The reality is, they are moneymaking enterprises. I’m not making a moral judgment on that. I’m not saying that’s the way society should or should not be. I have zero commentary on that. But it is a factual statement.” His professed lack of a moral stance was, nevertheless, a moral stance; he remains, first and foremost, a finance guy. (He even moonlights for Tilson, blasting out a newsletter on investing strategies to thousands of subscribers; recently he and Saincome unveiled a vertical, “Hard Money,” that’s a satire of day traders investing with internet platforms like Robinhood.) Abeyta has no desire to expose truth to power; he avoids negative or salacious coverage. By design, the outlets he has acquired are soft news, lifestyle, humor. Revolver features band interviews, vinyl spotlights, video premieres; Inked includes Q&As with celebrities about their tattoos, updates on the goings-on of viral tattooed TikTok-ers, and an “Inked Girl of the Week.” Geist told me, “We had a mission statement on the content side from the very beginning. One of those was to be very positive and community-building.”

Muckraking it’s not. Then again, there’s something appealing about the way Project M’s strategy has fostered loyalty. The metalheads want what they want; somebody’s got to cover it for them. I wondered if some version of that approach might be replicated elsewhere in media, and called Penny Abernathy, an expert in news deserts and the Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics at the University of North Carolina. “It’s much more difficult to create a sustainable business model for general news,” she said. “The print advertising model has clearly collapsed, and a digital model hasn’t come to be.” Still, she was interested in what local newspapers might be able to borrow from Abeyta—how he develops a sense of community and cultivates a variety of revenue streams. The few instances of success in local news, she said, typically feature a creative and disciplined leader who has strong ties to the audience being served.

The unlikely virtue of Abeyta may be his level of commitment. Hedge funds are predatory because their only goal is turning a quick profit; Project M, it appears, has sincere long-haul ambitions. That’s enough for Saincome. “There’s something about owning these things,” he said. “The person who owns it, at the end of the day, really should have some skin in the game.”

Alex Norcia is a freelance journalist who often writes about labor and drug policy. He has been published in the New York Times Magazine, The Nation, Salon, and Vice, among other outlets. He was born and bred in New Jersey, but is moving out west.