What Mohamed Soltan still can’t get over, six years later, is the smell. He rubs his fingers together, trying to conjure the odor, “of smoke mixed with tear gas and the iron smell of blood.” In 2013 he was a twenty-five-year-old graduate of the Ohio State University, living in Cairo in the chaotic days after a popular uprising had unseated Hosni Mubarak from Egypt’s presidency and a military council had taken over. But Soltan wasn’t like other Egyptian-American expats or some of the foreign correspondents he’d met that year who cheered when, in July, a military coup ousted the newly sworn-in president, Mohamed Morsi, of the Muslim Brotherhood. Soltan disdained outsiders parachuting in, looking for the most radical Islamist leader to give them a sound bite so that they could file their story, denounce the Muslim Brotherhood, and move on.

He wasn’t a Morsi supporter, either. Not like his father, a senior figure affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood and a professor at Cairo University who wrote treatises on Islam and the dangers of globalization to the Muslim family. Soltan was more moderate. And he had an idea: if these foreign journalists just spent time in Rabaa Square, where opponents of the coup had set up camp to protest Morsi’s removal, they would see that the activists represented varied interests and beliefs. (The group included some armed and violent protesters, but the vast majority of those assembled were peaceful.) So, during a sit-in lasting six weeks, Soltan joined the encampment’s media center. He crisscrossed the square, through its tent city, taking in the majestic mosque in the center, the vendors hawking skewers of grilled chicken, the stage where speakers recited from the Koran. He accompanied journalists from CNN, the BBC, Reuters, and Al Jazeera, trying to help them portray a nuanced view of the scene.

Then, in the early hours of August 14, gunfire erupted. There had been warnings before that the army was approaching, but those turned out to be rumors. Now, for more than eleven unspeakable hours, bullets flew from all directions. Even from the sky—snipers reportedly took positions in military helicopters. Soltan grabbed a gas mask, ducked behind the stage, and watched as an Al Jazeera cameraman was shot dead next to him. When the network’s crew tried to remove the man’s helmet and place it on another cameraman, so they could keep recording, Soltan saw that the helmet was smeared with blood and brain tissue.

Since Abdel Fattah El-Sisi was reelected, he has built on a foundation of policies that trample dissent and created a set of draconian new laws that criminalize anything his regime calls disinformation.

The whole time, he was taking pictures and live-tweeting what he saw. Then a bullet struck his left arm, “and it felt like being punched by the Hulk,” he says. The field hospital on the square—set up mostly to treat dehydration and suffocation—was so overwhelmed with casualties that Soltan felt guilty when he asked for painkillers. By the time the Rabaa massacre, as it came to be known, was over, more than a thousand protesters had been killed in what “likely amounted to crimes against humanity,” according to Human Rights Watch.

Soltan wandered the streets of Nasr City in a daze, nursing his injured arm, not quite believing what had just happened. Several days later, he underwent an emergency operation, in which two thirteen-inch metal nails were inserted into his arm. Then he needed a change of clothes. Specifically, he needed his American boxer shorts, because after a few months in Egypt he still couldn’t figure out Egyptian sizes; the ones he had been wearing chafed. Three journalist friends helped him make his way to his parents’ home. Shortly after 7pm, on August 25, a special-forces team raided the house, looking for Soltan’s father. Upon discovering that he wasn’t there, they arrested Mohamed and the other journalists. But the officers had only one pair of handcuffs, so they used it on Mohamed and tied up his friends with Mohamed’s American boxers.

Down at the police station, in a room known as “the fridge,” which was devoid of seats, windows, or light, Soltan was interrogated for hours about his tweets and his work with Western media outlets. He was blindfolded and beaten. Then he was jailed on charges of spreading false information and belonging to a terrorist organization—his case lumped together with those of more than thirty other people, including an influential activist-blogger and members of the Muslim Brotherhood. (The count would later mushroom to fifty-one, including Soltan’s father.) “When there was international pushback, they sprinkled onto our case some Muslim Brotherhood leadership to make it toxic and give it a scary name,” Soltan tells me, his lips knotting in an ironic smile. “And it worked.” Later, when Soltan was sentenced to life in prison, analysts would remark that mass trials had become a trademark of Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, the new president, who, after vanquishing Egypt’s Islamist opposition, commenced a crackdown on journalists and intellectuals for spreading “fake news.”

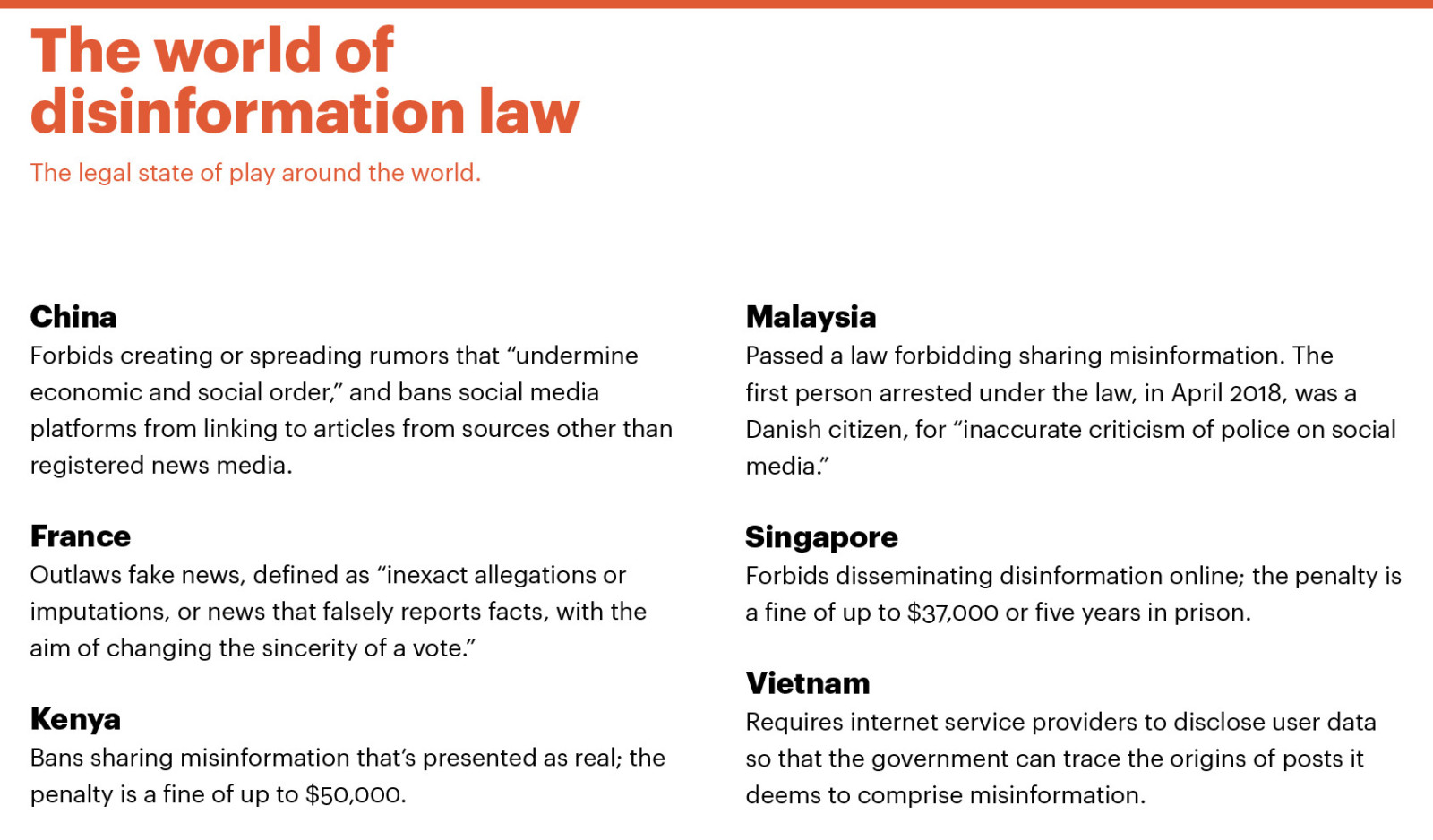

Since then, Donald Trump has made “fake news” a rallying cry against media he dislikes. And social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, which helped bring about Trump’s election, have revealed a tendency toward mendaciousness, as well as a need for oversight. Countries around the world have dashed to regulate against disinformation: Germany, France, Australia, Canada. Yet many countries have been blatantly underhanded, using the rush to implement onerous restrictions against journalists—see Cameroon, Rwanda, and Singapore. Uganda implemented a tax on social media use; bloggers in Tanzania are required to pay authorities to license their sites; Kenya passed a cybercrime law against the dissemination of “false” or “fictitious” news. These laws are paradoxical, deployed overwhelmingly by repressive regimes to target, censor, and imprison journalists who aim to cover fact.

In Egypt, we can see, already, where that leads. Since Sisi was reelected, last March, he has built on a foundation of policies that trample dissent like Soltan’s and created a set of draconian new laws that make “disinformation” criminal. On the one hand, there is the appearance of legitimacy, in that spreading false statements is now banned by a constitutional amendment cloaked in democratic language about the need to preserve the country’s “national fabric” and root out “discrimination, sectarianism, racism.” On the other hand, the assault on independent journalism has become furiously brazen. As leaders around the world take aim at “fake news,” Egypt’s efforts may be the most brutal, and the most foreboding.

Soltan and the journalists arrested with him after the Rabaa massacre were targets of the first sweeping imprisonment under false-information charges in the era that ushered in Sisi. But perhaps the most infamous case came four months later, with the arrest of three journalists working for Al Jazeera: Peter Greste, an Australian; Mohamed Fahmy, a Canadian; and Baher Mohamed, an Egyptian. After a trial—widely considered a sham and an embarrassment for the government, featuring video “evidence” that the three had never shot and a team of so-called experts who broke under cross-examination—they were each sentenced to at least seven years in prison in what the Obama White House said represented “the prosecution of journalists for reporting information that does not coincide with the government of Egypt’s narrative.” These cases marked the beginning of what would become a staple of the Sisi regime: the relentless pursuit of legal means by which to silence, intimidate, and crush independent voices.

Under Mubarak, there had been no official censorship mechanism. Analysts say that two restrictions were in place: there could be no reporting on the president’s health and no criticism of the military. In 2007, the editor in chief of Al-Dustour, a daily, was arrested for publishing “false information and rumors” about Mubarak’s declining health and was convicted of damaging public security and the Egyptian economy because of it. But the case was a rarity. Journalists were free, for the most part, to report critically without facing retribution.

In 2014, Mohamed Soltan, on trial for spreading false information, looks on while his father addresses an Egyptian court. Vasily Fedosenko/Reuters Pictures

In 2011, a national revolution transformed Egyptian politics and media: Mubarak was unseated and dozens of independent outlets and blogs emerged, amplified by the country’s growing use of social media. (In 2006, only 13 percent of Egyptians used the internet; by 2011, 36 percent did.) Sisi, who was appointed defense minister the following year, recognized the threat posed by an increasingly free press. He even said as much, as seen in a video leaked from a closed meeting with military officers in 2013. Sisi—slightly balding, with a squat face and jittery eyes—declares that the media “has been on our minds since the council’s first day. We’ve had a taste of that fire.” He adds: “It takes a long time to realize that you have significant control over the media and can interfere with it. We are working on that, no doubt. We’ve been achieving better results. But what we aspire to accomplish, we haven’t yet.”

The violent dispersal at Rabaa was a turning point in the narrative of the revolution, culminating with the election of Sisi, in the spring of 2014, with 97 percent of the vote. Outwardly, Egypt was cementing its status as a nascent democracy at war with radical Islamists of the Muslim Brotherhood and the Islamic State. But domestically, Egyptian media not only held its nose as Sisi trampled on civil liberties but also went out of its way to praise his policies. Sisi began to host monthly meetings with journalists and talk-show hosts, beseeching them: “If you have any information on a subject, why not whisper it rather than expose it?” Remarkably, they took his request to heart. That October, the editors of every major newspaper issued a joint statement vowing to support the regime in whatever way they could. These weren’t all state-owned outlets, either. The majority were independent.

By 2016, Sisi’s base began to erode, as he announced new austerity measures, including a major tax increase, that were deeply unpopular and received scathing reports in the press. Soon, the government began rounding up citizens en masse under a new counterterrorism law; according to the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, some 106,000 people were held in detention on various charges. Journalists who objected now posed a problem: whereas Sisi could once seize on their adulation to represent a seemingly free Egypt that enjoyed the support of the liberal intelligentsia, his constituency was becoming narrower and narrower by the day.

“Some believed that the regime would quickly establish a foundation for its legitimacy—but this never happened,” Amr Hashem Rabie, a political analyst, wrote in Al-Masri Al-Youm, an independent newspaper, that May. Listing reasons for alarm, Rabie cited events such as the storming of a journalists’ union, the devaluation of the Egyptian pound, and the torture and murder of an Italian doctoral student who was researching Egypt’s trade unions. “The important thing,” Rabie wrote, “is that all this is happening in conflict with the press, media, and protesters, while it is they who brought the regime to power.” He added: “There are currently more regime supporters than Muslim Brotherhood supporters in prison.”

As time wore on, Sisi needed a tool to keep critics in check while maintaining a democratic veneer. After he secured a second term with 97 percent of the vote (a landslide that human rights groups called “farcical”), he took up the task: last year, nineteen journalists were imprisoned on “fake news”–related crimes—more than twice the number of all other countries taken together, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Charges of spreading “fake news” have been consistently twinned with others, such as being a member of a terrorist organization or harboring an intent to undermine state security. Hussein Baoumi, Amnesty International’s chief researcher on Egypt, tells me, “In the eyes of the authorities, independent journalism has become a form of terrorism.”

The legislative offensive unfurled quickly. In March 2018, Egypt set up a hotline for citizens to report “fake news and rumors” and passed legislation against cybercrime, allowing authorities to block or shut down any sites that “endanger” Egyptian security. In April, Adel Sabry, the editor of a website called Masr al-Arabia, was arrested and fined the equivalent of $2,850 for republishing a New York Times article on possible irregularities during Sisi’s reelection. Authorities also fined Al-Masri Al-Youm about $8,500; Mohamed al-Sayed Saleh, the editor in chief, was subsequently fired over an article stating that Egypt had been “amassing” voters. The penalties were preposterous—even if the law could be accepted on its face, the claims reported were widely verifiable: the government had announced that any Egyptian who didn’t vote would be subject to a fine. “No one in Egypt produces more fake news than state-sponsored anchors or even the government itself,” Baoumi says. “But from the point of view of the government, even if they end up being fake news, they don’t undermine state security and therefore they’re fine.”

Later that month, Ahmed Abdel-Al, Egypt’s chief meteorologist, proposed legislation that would punish anyone “talking about meteorology, or anyone using a weather forecasting device without our consent, or anyone who raises confusion about the weather,” as he said in a televised interview. The bill has since been drafted into law, though apparently it has yet to be applied.

By June, the Egyptian parliament passed another law, giving the state power to block social media accounts and penalize citizens for publishing disinformation. According to the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression, an Egyptian watchdog group, more than five hundred websites have since been blocked in the country. Independent reporters are especially vulnerable, because they can now be personally subjected to disinformation fines of up to $14,400. In practical terms, the law has also meant that any Egyptian with a Facebook following of at least five thousand can, in theory, be prosecuted for “fake news”–related offenses.

When it comes to defining what “fake news” is, prosecutors have been murky. The law does not even require them to identify what false information, exactly, they accuse their targets of spreading. When they try, it often leads to Kafkaesque situations: Last year, Amal Fathy, an Egyptian actress and political activist, posted a video on Facebook lambasting Egypt’s record on sexual harassment. During her trial, she was grilled by state prosecutors: “In your video, you said that Egyptian men are worse than zombies. What’s your evidence for that?” Fathy was later sentenced to two years in prison.

Journalists are left with essentially one path: praise. “When Sisi talks about something, anything, all media organizations are required to cover Sisi’s ‘brilliance,’ ” Mohamad, an Egyptian journalist who asked that his last name be withheld for fear of retribution, tells me. “The only things that get published are those that the Egyptian government decides on, or the security services. Meaning, I can’t criticize a minister, or disagree with their policies. I can’t say that anyone is oppressed or suffering. I can only say that the ministers are right, that everything they’re doing is right, that Sisi is right, the security forces are right.”

In another move toward seeming transparency but greater restriction, the state’s Information Ministry, long considered a propaganda arm of the regime, has been replaced with a new body, the Supreme Council for Media Regulation. The law stipulates that its members be media specialists and that the institution be independently run. In practice, however, Sisi has packed its ranks with cronies; the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression reported earlier this year that all but one of the nine members were chosen by him. “In the past, we always asked for an independent body and believed that such a council can be good,” Negad El-Borai, an Egyptian lawyer with a long history of representing media organizations, tells me. “But because of the members of this council, they use it as a weapon in the hands of the government, and they use it to go after freedom of expression.” Media council members have spoken out in support of censorship—a staggering fact for a body supposedly dedicated to ensuring press freedom, though perhaps not surprising when you consider that most of its members don’t work in the press. Makram Mohammed Ahmed, the head of the council, has described critics of the Sisi regime as “a group with a loud voice who stands against the state with rumors.”

Journalists in Egypt often have no recourse but to publish rumors; the government has asserted that it alone can provide information on national security, yet getting Sisi’s administration to do so swiftly and accurately, reporters and lawyers argue, is next to impossible. Take a recent example, one Egyptian journalist tells me, citing an explosion outside Egypt’s National Cancer Institute this August. “At first, the security forces leaked information that the explosion was caused by oxygen tubes; then they said it was caused by a car crash,” the reporter recalls. “These are all official, security-affiliated reports, yes? Meaning, issued by the Interior Ministry. Then, more than twelve hours later, the Interior Ministry ‘discovered’ that the explosion was a security incident and released a statement saying it was an act of terrorism.” At any step along the way, the journalist adds, if a reporter failed to keep up with the changing narrative, he (it’s usually a he) could have been slapped with a charge of spreading fake news and placed behind bars.

Not every reporter gets locked up, of course. Many are simply intimidated into silence.

Not every reporter gets locked up, of course; that would be impractical. Many are simply intimidated into silence. Over the past few years, Egyptian authorities have ramped up their use of informal—and illegal—interrogation, wherein journalists and editors are shaken down for sources, numbers, and opinions. It often begins with a phone call from the state security agency, asking a journalist or an editor to “come by,” according to Gamal Eid, a prominent rights lawyer. “We advise them not to go. But because many fear for their families, they go.” Eid, who heads the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, has tried to accompany several independent journalists to these interrogations but has always been denied entry; because the questioning is considered unofficial, attorneys cannot be present. Such interrogation has become so commonplace, Eid says, that an old police academy in the Cairo neighborhood of Abbasiya has been converted, in part, for that purpose.

Often, those interrogated are then released, supposedly free, except that many are so cowed that they don’t go back to publishing at all. At least three Egyptian journalists now work as Uber drivers. Several work in cafés. Others have fled the country. Among those who do go back to their jobs, many practice a form of self-censorship so ingrained that it doesn’t take an official apparatus to enforce. Mostafa Bahgat, a television correspondent, has described to The Guardian how, in covering the clashes between the Brotherhood and the police in 2013, he filmed only from the side of the security forces, to avoid footage of people getting killed. “Just like doctors who do the same operation many times, they get used to it,” he said. “Self-censorship is what I feel I should do all the time.”

The few journalists who continue to report critically do so at grave personal risk and without the guarantee of institutional backing. Even at a fiercely independent outlet such as Mada Masr, a bootstrap operation founded in 2013 by young progressive journalists, writers have taken to posting their articles anonymously for fear of reprisal. Mada Masr is now blocked inside Egypt. Some of its staff members have been attacked or had their emails hacked, according to Baoumi, of Amnesty International.

Recently, Sisi has moved not only to silence independent journalism but to buy it outright. A conglomerate known as the Egyptian Media Group—which has several outlets, including the satellite channel ONtv, six print publications, and two film and television production companies—was founded in 2016, supposedly by a pro-Sisi steel magnate named Ahmed Abou Hashima; in fact, Hashima’s role in the company was mostly a cover, according to an exposé in Mada Masr, and Egypt’s general intelligence service, the Mukhabarat, owned a controlling stake through a private equity fund called Eagle Capital. In 2017, Eagle Capital bought Hashima’s minority share, to attain full ownership of the company. “As soon as those contracts were signed there were new editorial lines, there were several people who went off-air, who took leave and never came back,” Sherif Mansour, the Middle East program coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists, tells me.

One of those was Liliane Daoud, a respected Lebanese-British talk show host whose program Al Soura Al Kamila (“The Full Picture”), on ONtv, aired opinions that were critical of the government. A month after the Egyptian Media Group acquired ONtv, Daoud was detained by plainclothes officers at her home in Cairo for allegedly overstaying her visa and deported to Beirut. Similarly, three journalists for Youm7, a widely read newspaper, were reportedly fired in 2017 for criticizing the government’s transfer of two Red Sea islands to Saudi Arabia.

Since then, it has become common practice for news items to be dictated by security forces and then sent to editors, ready for publication, through WhatsApp. “The Mukhabarat have completely taken over,” Mohamad, the Egyptian journalist, says. An editor once told him: “We’re in the same position as you, but slightly more senior. We are no longer editors in chief. We are subjected to orders.” Allison McManus, research director at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, adds that some outlets now answer to state intelligence officers, who use informants to monitor goings-on in the newsroom.

A gaffe made on-air this year sheds light on the degree of government intervention. In June, Mohamed Morsi collapsed in an Egyptian courtroom and died, aged 67. State-run channels reported on his death but just barely, gliding over the fact that he had been president. Broadcasts of the event were so terse and carefully worded that a host for Extra News TV, which airs on a channel also owned by the Egyptian Media Group, accidentally concluded her report by reading out: “This was sent by a Samsung device.”

Mohamed Soltan was kept in an underground cell at Tora Liman, a maximum-security prison. When the time came, he was too weak to attend his own sentencing trial. For 489 days he went on a hunger strike; he’d shed a hundred and fifty pounds and kept slipping in and out of consciousness, his blood so thinned and drained of nutrients that it began to leak out of his mouth in his sleep. He managed to send a letter to his family that was smuggled out of prison and shared with David D. Kirkpatrick of the New York Times. “My body has become numb as it eats away at itself,” Soltan wrote.

Month after month, his family led a tireless advocacy campaign for his release. And then, in May 2015, in the dead of night, Soltan was taken from his cell directly to the Cairo Airport, where a consular attaché and a nurse waited to accompany him on a flight to Washington, DC. Once a chubby and easy-to-laugh basketball player, he had to be wheeled into the arrivals hall, where a throng of family, friends, and supporters waited for him.

Freedom, when it came, was unexpected. There had been no reversal of his verdict. No clearing of his name. No presidential pardon. Instead, a loophole was found in a 2014 law allowing foreigners to be deported to their home countries to serve out a sentence or be retried. It meant that Soltan had to relinquish his Egyptian passport—a fact that, despite his ordeal, continues to trouble him.

Eid, the rights lawyer, says that Soltan’s case and his eventual release marked a watershed moment in Egyptian jurisprudence as “the beginning of discrimination against Egyptians in favor of foreigners.” This is another chilling irony of Sisi’s clampdown: that, while purporting to protect Egyptian identity from those who seek to destroy it, his government in fact treats its own citizens as worthy of fewer rights than foreigners (especially Westerners). Had Soltan not been a US citizen, he would likely still be imprisoned for crimes he never committed. Egyptians deserve better, Eid argues, and so does Soltan: “He deserves to be released because he is innocent, not because he is a US citizen.”

These days, to chat with Soltan is to experience a kind of cognitive dissonance. You have to remind yourself of what he has endured—what he and his family still have to endure, as his father serves out a life sentence—because there is no outward sign of his experience. His musculature is back. He carries himself with a casual swagger. His hair has grown out a little: a widow’s peak is beginning to announce itself. He is now studying for a master’s degree in foreign service at Georgetown University and heads the Freedom Initiative, a rights group he founded to advocate for prisoners of conscience in Egypt and Saudi Arabia. “I’m even dieting now, so that’s a very good sign,” he says.

But his tone turns serious when he is asked about Egypt’s use of the new disinformation laws as a crackdown on dissent. To Soltan, the notion that “fake news” charges in Egypt are somehow a new phenomenon smacks of hypocrisy and elitism. Where was the international outrage when the Sisi regime “only” went after alleged Muslim Brotherhood sympathizers? When it “only” imprisoned journalists with alleged Islamist leanings? To him the trajectory of human rights violations and the trampling of freedom of expression were spelled out six years ago, with the Rabaa arrests.

He tells me, “The general methodology of the Sisi regime always starts off with the Islamists, and they kind of use them—for lack of a better term—as lab rats to test whether there will be any pushback on this tool of repression, and when there isn’t pushback from the international community, then they extend this repression tool onto other subsets of civil society and human rights organizations. And then, when there isn’t pushback on that, then they extend it to the general population. You look at every tool of repression—you look at imprisonment, you look at torture, you look at disappearances, you look at extrajudicial killings—they always start with the Islamists.”

“People get normalized to hear of ‘fake news’ in democratic societies,” Mansour, of the Committee to Protect Journalists, tells me. “But it doesn’t reflect or capture how much this has been used and continues to be used today in very cruel and vindictive ways to punish journalists around the world. While many international outlets enjoy protection and support of the public when those topics are invoked, I feel that they don’t get as much attention when they are invoked in countries where those protections do not exist and where the public interest has no value.”

In September, a building contractor named Mohamed Ali, who lives in self-imposed exile and had worked on projects for the Egyptian military, began posting videos alleging government corruption and calling for Sisi’s resignation. Soon, hundreds of Egyptians took to the streets in scattered protests—a rare act of public defiance. Authorities responded with a sweeping clampdown, using tear gas and rounding up more than 2,300 people, according to Amnesty International. At least six Egyptian journalists were arrested for their role in covering the demonstrations. One independent newspaper, Al-Mashad, prominently featured Ali’s allegations, including other reports of mismanagement of state funds. The morning after the newspaper ran those articles, the son of Magdi Shandi, the editor in chief, was arrested in a raid on the family’s home, with no explanation given as to why or under what charges. In an emotional note on Facebook, Shandi applauded the courage of his fellow journalists for speaking out and trying to “end the crisis.” In November, security forces arrested a senior editor of Mada Masr and, according to press accounts, deported another editor, who is an American citizen. Again, the authorities offered no explanations or warrants.

Soltan now watches such cases from across an ocean, with growing dismay at how emboldened the Egyptian government has become. “They get away with it so much that they have to legalize it, to be able to tell the rest of the world, ‘Hey, back off, we have laws to legalize this now. This is our system.’ ”

Ruth Margalit is an Israeli writer. Her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, and the New York Review of Books. Follow her on Twitter @ruthmargalit.