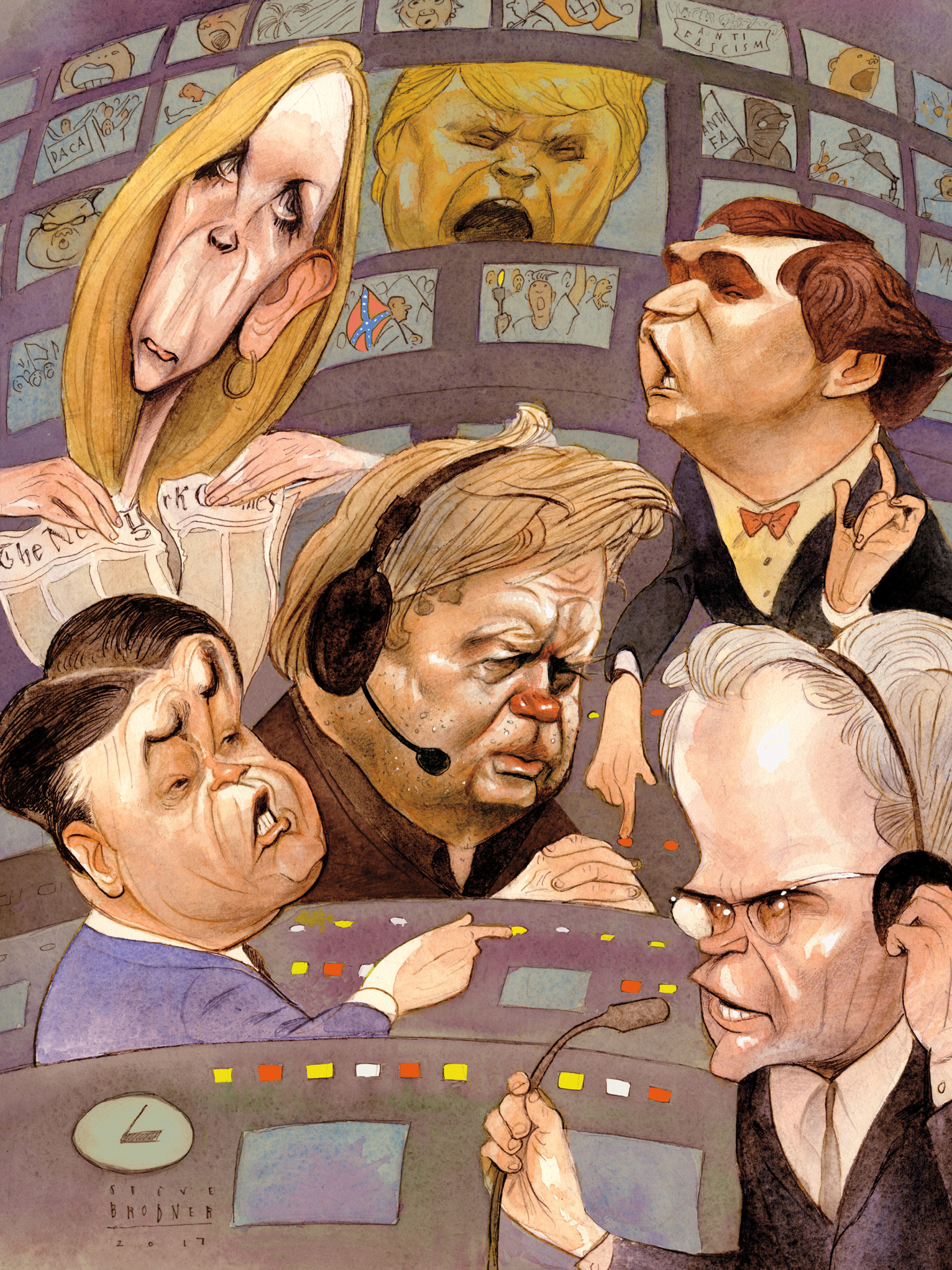

It was a sweltering July afternoon in the swamp, and a small group of well-dressed, conservative college students from across the country—the next generation of Megyn Kellys, George Wills, and Tucker Carlsons—was filing into an auditorium at the Heritage Foundation’s Washington, DC, headquarters. They had come to study at the feet of Breitbart News Washington editor Matt Boyle, a zealous prophet of the new right-wing media. Boyle’s sermon was not about how to break into the mainstream media and steer the national news agenda toward conservative aims—it was about the end days of journalism itself. And he was not about to skimp on the fire and brimstone.

“Journalistic integrity is dead,” he declared. “There is no such thing anymore. So everything is about weaponization of information.” Standing behind a mahogany podium in a baggy dark suit, Boyle preached with the confidence of a true believer. In a stuttering staccato, he condemned the nation’s preeminent news outlets as “corrupted institutions,” “built on a lie,” and a criminal “syndicate that needs to be dismantled.” Boyle and his compatriots were laboring to usher in an imminent—and glorious—journalistic apocalypse. “We envision a day when CNN is no longer in business. We envision a day when The New York Times closes its doors. I think that day is possible.”

Squint at the Trump era, and it’s easy to see a conservative media in crisis. Over the past 18 months, we have witnessed the fall of Bill O’Reilly, the ouster (and death) of Roger Ailes, prominent conservative outlets from Fox News to Breitbart to The Wall Street Journal op-ed page erupt in upheaval and infighting, Milo Yiannopoulos lose his book deal, and Tomi Lahren lose her job at The Blaze (only to land at Fox). Look closer, though, and you’ll see that much of that drama was simply a function of the outlets’ increased political power (and the heightened scrutiny that’s followed)—a bit of routine turbulence accompanying the unprecedented ascent of the right-wing media.

ICYMI: You might’ve seen the Times‘s Weinstein story. But did you miss the bombshell published days after?

While Donald Trump’s rise may have, as Politico’s Eliana Johnson recently wrote, “scrambled the pecking order” on the right—elevating Breitbartesque populists over the conservative intellectuals at the Journal and The Weekly Standard—the conservative media complex as a whole is bigger, stronger, and more influential today than it’s ever been. And with so many of its most powerful members now pursuing a scorched-earth assault on America’s journalistic institutions, it’s worth considering what they hope it will look like once they’re done burning down our villages, desecrating our temples, and howling at our lamentations.

Boyle said his goal was simple: “The full destruction and elimination of the entire mainstream media.” Breitbart played up his speech on its homepage that day, but the remarks barely registered in broader media circles. The site and its staff have become known for this kind of bluster, and most journalists have taught themselves to tune it out. Maybe we ought to be paying closer attention.

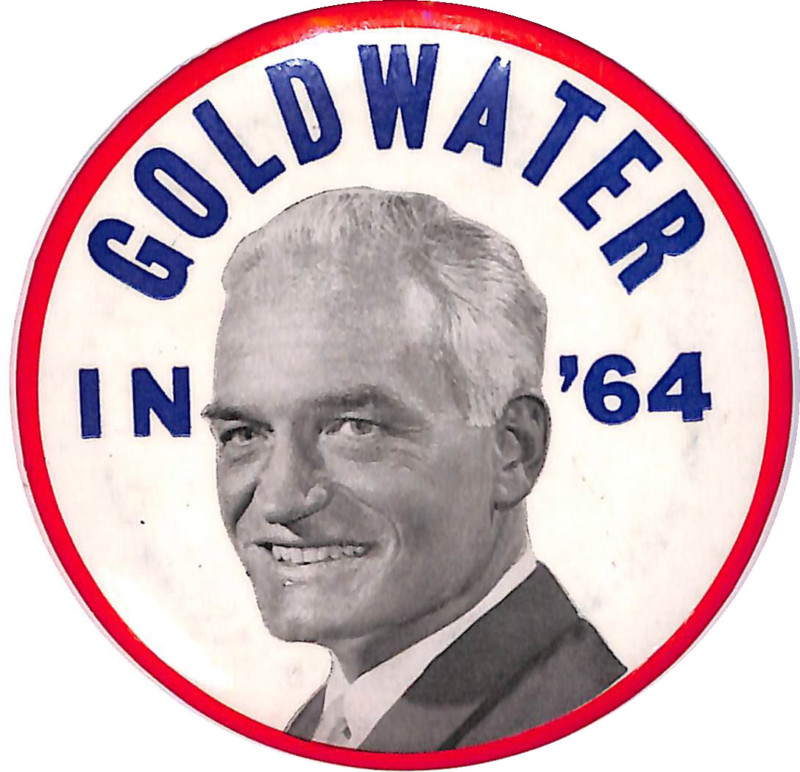

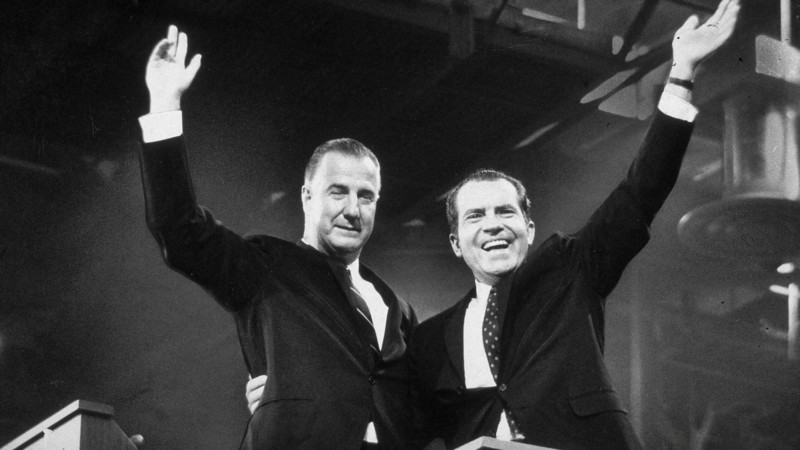

There is a long tradition in Republican politics of seeking to discredit journalism. During the 1964 presidential campaign, Barry Goldwater’s press secretary distributed gold pins to reporters that read “Eastern Liberal Press.” Richard Nixon’s vice president, Spiro Agnew, in 1969 railed against the “closed fraternity of privileged men” who ran the national news broadcasts. Nixon’s presidency was ultimately felled by reporters, but the critique lived on.

In the decades since, charges of liberal bias (some of them valid, others less so) have practically become an official plank of the GOP platform. The subject has inspired scores of books, countless talk-radio rants, and the creation of an entire cable news empire whose slogan—“Fair and Balanced”—was coined as a condemnation of its competitors.

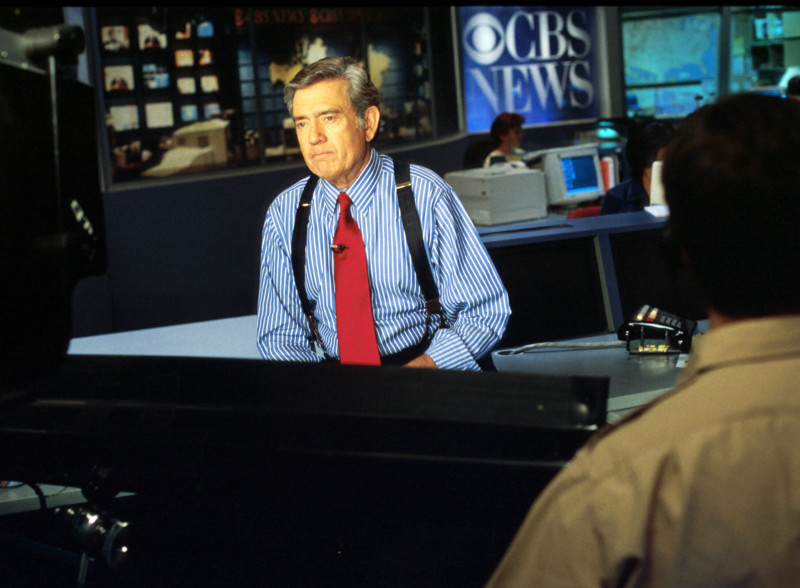

Crucially, though, for most of that period conservatives maintained a civic-minded rationale for their project. They said they believed in the importance of nonpartisan journalism; in the necessity of a strong, independent press that provided the citizenry with an accurate account of the day’s events. Ultimately, they claimed, they were practicing tough love—offering their criticisms in the spirit of reform. Bernard Goldberg—a CBS News veteran whose tell-all book Bias entered the conservative canon as soon as it was published in 2001—captured this sentiment during a segment on The O’Reilly Factor. “We all know that you can’t live in a free country without a free press,” Goldberg told host O’Reilly. “But you know what else? You can’t live in a free country for long without a fair press. We need a strong mainstream media. That’s why you and I criticize it.”

Of course, some of this stated concern for the Fourth Estate and its lack of objectivity has been disingenuous. But there was value even in the playacting. By paying lip service to the ideal of “fair and balanced” news, conservatives helped sustain the post-WWII consensus that our modern democracy works best with a robust nonpartisan press functioning as the common denominator.

It was Donald Trump who dropped this pretense. Rather than conceal his true meaning with earnest pleas for a fairer press, he fired off tweets casting the media as “enemy of the American people.” Rather than feign reverence for the First Amendment, he promised to “open up our libel laws” to make suing journalists easier. At campaign rallies, he would keep reporters confined to metal press pens, and lead his crowds in a ritualistic booing. As someone who covered dozens of those events, I always thought I could tell when he was going through the motions with his press-bashing, and when he really meant it. During particularly bad news cycles, his voice would take on a growling quality, and he’d punctuate his standard stump-speech line with an extra exclamation: “Absolute scum. Remember that. Scum. Scum. Totally dishonest people.”

Trump’s histrionics were always strategic. He was able to successfully undermine months of critical coverage and dutiful fact-checking by casting reporters as villains. Each time his campaign was in trouble, the candidate escalated the culture war on the press. By the end of the election, we were not just biased or corrupt—we were dangerous, conspiratorial, part of a shadowy globalist cabal. Just days after Trump was sworn into office, chief White House strategist Steve Bannon told The New York Times, “You’re the opposition party. Not the Democratic Party . . . . The media’s the opposition party.”

Bannon’s first move after being dismissed from his White House posting was to huddle with the billionaire Republican donor Robert Mercer who has backed his right-wing populist media crusade. On the afternoon of his firing, he said in a statement to Joshua Green, author of Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump and the Storming of the Presidency, “If there’s any confusion out there, let me clear it up: I’m leaving the White House and going to war for Trump against his opponents—on Capitol Hill, in the media and in corporate America.”

It doesn’t require an overly active imagination to picture the post-apocalyptic news landscape that so many conservatives seem to be working toward. Media fragmentation accelerates to warp speed. Agenda-driven publishers—be they professionally staffed websites or one-man YouTube channels—churn out narrowly tailored news for increasingly niche audiences. There’s still plenty of factual reporting to turn to when you want hurricane updates or celebrity news, and adversarial investigative journalism doesn’t quite go out of style. But it’s easier than ever for news consumers to ensconce themselves in hermetically sealed information bubbles and ignore revelations that challenge their worldviews. For most people, “news” ceases to function as a means of enlightenment, and becomes fodder for vitriolic political debates that play out endlessly on social media. (Like I said, it’s not hard to imagine.) Inevitably, the rich and powerful—those who can afford to buy and bankroll their own personal Pravdas—benefit most in this brave new world.

This is, of course, a worst-case scenario. But is it really so far-fetched? Already, many of the nation’s most important outlets—the publications and networks that comprise the core of American journalism—have seen their audience shrink and splinter; their credibility plummet among vast swathes of the public; and their financial futures turn bleak. If The New York Times and ABC News were to shut down or, more likely, dwindle into shells of their former selves, would they be replaced with new mega-outlets that share their resources, their reach, and their editorial values? It’s possible. But it seems just as likely that they wouldn’t be replaced at all.

“This whole idea of media objectivity is relatively new,” says Ben Shapiro, a former Breitbart editor at large who founded and runs the right-wing website Daily Wire. Like other conservatives I talked to, he envisions a return to the media conventions of centuries past, when news was delivered largely by the organs of parties and ideological movements. “At the founding, it was a bunch of partisan press going after each other.” If Shapiro had his way, the news would be a polemical free-for-all and media outlets would give up any pretense of non-partisanship. He dismissed the Pulitzer-winning fact-check site PolitiFact as a “leftist outlet,” and generally rejected the idea that any news organizations should be held up as “grand arbiters of truth and falsity.” The very notion, he says, is “anti-democratic.”

“Basically, I think we ought to get away from drawing strict boundaries around ‘journalism,’” Shapiro told me. He pointed to James O’Keefe, a conservative activist who is famous for producing secretly recorded (and often selectively edited) videos that purport to expose the sins of academia, the media, and the government. “Is he an activist?” Shapiro asks. “Yes. Does he commit journalism? Yes. Is he a journalist? Well, it depends on whether he’s committing acts of journalism in that moment.”

Ann Coulter, the vociferously pro-Trump pundit and author, echoed these sentiments in our email exchange. She told me that virtually all news coverage of the president by the “elite” media—a group she says includes not just The Washington Post and NBC, but also many old-line conservative publications—has been dishonest, frivolous, and pack-like. “Chuck Todd agreeing with Jeff Flake about what a barbarian Trump is isn’t news!” Coulter says. “I guess what I’d like, in my ideal world, is that we all start arguing about issues and ideas.”

I asked her if there was any room in that vision for news outlets that play a neutral, referee-like role—contributing to the debate only by adding facts and debunking falsehoods. Coulter seemed uninterested in the question. The publications that have tried to serve that function, she contends, have become “too screechy and inaccurate,” and have rightly lost the public’s trust. “No serious person would trust either the NYT or WaPo’s ‘FACT CHECK’!”

The concept of an obstinately objective press has been under assault in America for some time now, of course, and not just from the right. Critics like NYU’s Jay Rosen argue persuasively that news outlets do a disservice to their audiences when they coat their journalism in a sheen of artificial neutrality. Better to aim for transparency, the argument goes—to be honest about where you’re coming from, and to then strive for fairness and open-minded engagement. But there is a considerable difference between the proponents of this theory and those who cynically celebrate the “weaponization of information” and the rise of “alternative facts.”

The so-called marketplace of ideas only works when reality serves as a regulating force. For constructive debates to take place in a society like ours—and for national consensus to emerge on any given question—it’s essential we start from a broadly agreed-upon set of basic facts. Who will provide them if the mainstream media collapses into a melee of warring partisan publications?

Late one afternoon in July, I met with Matthew Continetti, editor in chief of the Washington Free Beacon, in a pizzeria on the ground floor of the Watergate—the DC office complex that stands today as a concrete brutalist monument to the most iconic journalistic triumph of the 20th century. Continetti is not a bomb-thrower by nature. He is polite and cerebral and meticulous about his diction—often pausing for several seconds to consider his words before answering a question. On the day we met, he had just come from George Washington University, where he teaches a class on the history of the intellectual conservative movement.

Continetti grew up in the middle-class suburbs of northern Virginia with parents whom he describes as not “particularly political.” His conversion to conservatism came at Columbia University, while studying Plato’s Republic during an undergrad class on political philosophy. It was around this same time that he decided to pursue journalism, writing articles for the student newspaper as well as for a conservative national magazine called Campus. Aspiring journalists who lean to the right often face a choice as they prepare to enter the industry: try to carve out a career in the mainstream press, or follow the well-trod path into conservative media? Continetti opted for the latter—working as an intern at National Review while he was attending Columbia, and becoming a star writer at The Weekly Standard after graduating. (In 2012, he married Anne Kristol, the daughter of Bill Kristol, the magazine’s founder.)

The site Continetti edits today contains a fair amount of trolling—a running series of Kate Upton clickbait; winking headlines like “Greatest Living President Is Also Fantastic Painter”—but it has also earned a reputation for real-deal journalism. Its reporters run down leads, work their sources, call for comment, and issue corrections when necessary. If a partisan press really is the future, we could do worse than the Free Beacon.

I hoped Continetti might have a more optimistic outlook on the world after the mainstream media’s demise. But as we spoke, he was unremittingly bearish on the prospect that any 21st-century outlet could win the trust of a broad, diverse cross-section of news consumers. “One of the reasons there’s no common denominator in media is there’s really no common denominator in American life,” he told me. “As a general rule, we are a divided society. We have very real disagreements about values, about what’s important.”

I couldn’t help but interject: Shouldn’t facts be the common denominator? I asked, painfully aware that I was exhibiting the kind of journalistic sanctimony that the Free Beacon regularly ridicules.

Continetti exhaled, patiently, and shook his head. “I think the problem you describe is unsolvable,” he told me. “People are going to believe what they want. It’s not my job to tell them what to believe. It’s my job to edit a site that provides new information and adds value every day. Certainly, there are many people, like Howard Dean, who say it’s ‘fake news.’ But OK, I’m not going to control what Howard Dean thinks. He has every right.” A smirk appeared on Continetti’s face. “And I don’t believe a word he says, either.”

In many ways, Donald Trump was the perfect candidate to channel the conservative media—the talk radio id personified and plopped onto a debate stage. As someone whose status as a perpetually aggrieved media critic long predated his conversion to conservatism, Trump quickly discovered that rank-and-file Republican voters were an enthusiastic audience for his gripes about the press. And as Trump worked to reinvent himself as a Republican political celebrity, he naturally took his cues from the popular right-wing media. His first major foray into conservative politics was as the world’s most famous “birther,” championing a conspiracy theory that was gaining steam on talk radio and right-wing blogs. Later, as a candidate, he punctuated his stump speeches with stories he’d read on Breitbart and parroted the talking points he’d picked up watching Fox & Friends.

Trump did face real opposition in the primaries from the conservative intelligentsia. Kristol and New York Times op-ed columnist Ross Douthat were early and outspoken critics, while National Review published an entire anti-Trump issue in the run-up to the Iowa caucuses. But those with the loudest megaphones—people like Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity—saw Trump’s affection for them and their tribe, and rewarded it by providing the kind of boosterism that Mitt Romney would have sold one of his sons for.

And so, when Trump won in 2016, it wasn’t just a victory for him and his campaign. It was a coup for the conservative media, whose destructionist attitude toward the mainstream press can now be found at virtually every level—from the hosts of Fox News, to the ascendant internet personalities of the alt-right. “Nothing is grander, nothing is more glorious, nothing is more satisfying, nothing is sweeter, nothing is more validating, nothing is better for America than the death of the mainstream media’s political power,” John Nolte crowed in the Daily Wire the day after the election.

The Gateway Pundit flatly declared, “The mainstream media is your enemy.” And Infowars captured the sentiment by featuring an editorial cartoon depicting right-wing media figures as asteroids hurtling toward earth where news-network dinosaurs await their “extinction.”

In a decidedly dystopian spin on service journalism, some in the conservative media have begun providing their audiences with how-to guides for finishing off the journalistic establishment. Limbaugh told his listeners they should stop consuming news from the mainstream press altogether. “I’ll let you know what they’re up to,” he assured them. “And as a bonus, I’ll nuke it!” Hannity urged his viewers to start targeting individual journalists—and their bosses—on social media. And the alt-right blogger Roosh Valizadeh has called for a coordinated campaign of bullying aimed at reporters. “Make them appear as ‘uncool’ salarymen in the eyes of the public,” he wrote. “Mock their appearance, their mannerisms, and their weaknesses.”

It would be easy to dismiss all this as performative, and ultimately harmless, trolling. But if the Trump era has taught us anything, it should be that these elements of the conservative media are not to be underestimated. In 2016, they conquered the Republican Party. Now they’re coming for the press.

Mainstream’s right turn

Today’s right-wing media world didn’t surface overnight. Below, a timeline of its development.

—Pete Vernon

1947

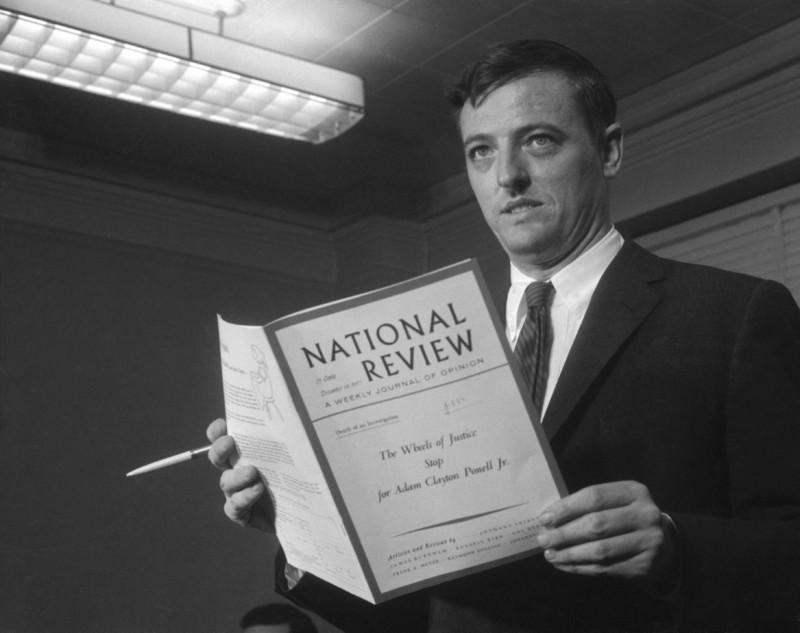

Henry Regnery founds conservative book and magazine company Regnery Publishing. William F. Buckley Jr. later advises him: “I would recommend that you state that in your opinion an objective reading of the facts tends to make one conservative and Christian; that therefore your firm is both objective and partisan in behalf of these values.”

1954

Clarence Manion begins the Manion Forum radio show, of which he bragged, “Every speaker over our network has been 100 percent Right Wing . . . . You may rest assured, no Left Winger, no international Socialist, no One-Worlder, no Communist will ever be heard over the 110 stations of the Manion Forum network.”

1964

So frequently does Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign complain about bias in the coverage of his candidacy that his press secretary jovially hands out pins that read “Eastern Liberal Press” to the reporters on the campaign plane.

1969

Vice President Spiro Agnew gives a televised speech complaining about how President Richard Nixon’s Vietnam War policies are covered by the press. “Perhaps the place to start looking for a credibility gap is not in the offices of the Government in Washington,” he says, “but in the studios of the networks in New York.”

1973

Nixon supporters dismiss the Watergate scandal as a witch hunt by a liberal media. “Watergate,” says Senator Jesse Helms, “became the lever by which embittered liberal pundits have sought to reverse the 1972 conservative judgment of the people.”

1988

The Rush Limbaugh Show quickly becomes one of the country’s most popular syndicated radio programs. “In those days the mainstream liberals had a media monopoly,” Limbaugh later says. “Nobody did political talk, let alone conservative political talk.”

1996

Announcing the Fox News Channel, its chief executive Roger Ailes says the 24-hour news network “would like to restore objectivity where we find it lacking . . . . We just expect to do fine, balanced journalism.”

2004

Dan Rather steps down as CBS Evening News anchor after memos in a CBS report alleging George W. Bush received preferential treatment while serving in the Texas Air National Guard are revealed by conservative bloggers as fakes.

2009

Andrew Breitbart announces that his eponymous website will launch a “Big Journalism” vertical with the intention to “fight the mainstream media . . . who have repeatedly, and under the guise of objectivity and political neutrality, promoted a blatantly left-of-center, pro-Democratic Party agenda.”

Donald Trump gestures during a rally in August 2017 in Phoenix, Arizona. (Photo by Ralph Freso/Getty Images)

2016

Donald Trump makes attacks against journalists a hallmark of his presidential campaign. He bans a number of outlets from attending his rallies and events. Less than a month after taking office, Trump refers to the media in a tweet as “the enemy of the American People!”

ICYMI: The first reporter to arrive at Vegas gunman’s house has covered the story in many ways–except one

McKay Coppins is a staff writer at The Atlantic. He was previously a reporter for BuzzFeed News, where he covered two presidential campaigns, and before that he wrote for Newsweek. He is the author of The Wilderness, a book about the battle over the future of the Republican Party.