Bitter Lake, in northwest Seattle, derives its name from the acidic residue of a long since demolished sawmill. Small and oblong, it now hosts noisy, profusely defecatory gaggles of Canada geese and sits beside houses, apartments, and the Broadview Thomson elementary and middle school. In the spring of 2020, camping tents began to pop up along the wooded southern edge of the lake, adjacent to Broadview Thomson’s ball field. A few dozen people in need of housing moved onto the land, which is owned by the local school district.

One afternoon this past May, Samira George, the features reporter for Real Change, a weekly newspaper attached to a nonprofit of the same name, arrived at Bitter Lake to interview residents of the encampment. George, who is twenty-six, was first sent there on a tip: a woman who lived in a house nearby had gotten to know the newcomers and felt disturbed by how they were portrayed on KOMO-TV, a local station owned by the conservative Sinclair Broadcast Group. The coverage she’d seen drew on demeaning tropes of homelessness: allegations of “violence,” “drug use,” “property crimes,” a “half naked” “sex worker”; there were panning shots of tents and shopping carts and interviews with angry parents and business owners. The woman reached out to Real Change and connected George to the residents, hoping to get a more humane story before the public.

Reporting from the camp, George spotted a couple of men talking and asked if “Tony” was around. Anthony Pieper and his partner, Shelly Vaughn, were living in a large tent beneath a stand of trees. George had met Pieper once before, on an earlier visit to Bitter Lake, and he gamely answered her questions—about when he and Vaughn had arrived, interactions with activists and reporters, access to bathrooms and garbage cans. Vaughn kept a journal, which she showed to George, reading aloud from a response she’d written to an especially hurtful KOMO segment.

“Making Bitter Lake home” appeared as a full-color centerfold in the June 2 issue of Real Change. The article was both a profile of Vaughn and Pieper and a critique of TV news as brokered by a self-proclaimed homeless-rights activist who “will pop up at their encampment, walk around for roughly 30 minutes, take photos or videos and offer to pick up trash, which the campers are OK doing themselves,” George wrote. The story sidestepped any concern for orthodox notions of balance: Pieper and Vaughn were presented in their voice, but there was no quote from the activist, nor from the KOMO reporter who had filed so many sensationalized stories about the camp, nor from a mayoral candidate whom Pieper accused of scapegoating homeless people.

A week before the story came out, I’d sat in on an editorial meeting with George and the other two members of the Real Change newsroom, held over Zoom. “Nobody’s actually talking to people living in the encampment,” George said. That bothered her especially because her brother was homeless, living out of his car in Northern California. She discussed the framing of her piece with Lee Nacozy, the managing editor, and Henry Behrens, the arts editor and designer. If, for instance, someone in a tent were doing drugs, would it be appropriate to portray that? To publish a photo of used needles? “What is accurate yet fair in advocacy journalism?” Nacozy wondered.

Real Change has always done advocacy journalism, which Nacozy—a forty-year-old former staffer of the Austin American-Statesman—said she is still getting used to. Real Change, the umbrella organization, has a three-part structure: newspaper, vendor program, and advocacy department. Homeless and low-income people can sign up with Real Change, the nonprofit, to sell Real Change, the newspaper; vendors buy the paper at sixty cents per copy and sell it for two dollars plus tips. “The newspaper has two bottom lines,” Shelley Dooley, the managing director, told me. “It’s one of the last weekly papers and provides information from the participant perspective. The other is, the newspaper is a widget for vendor income.” To keep the newsroom independent, Real Change maintains an institutional firewall; if the advocacy team is presenting at a city council hearing, the Real Change reporter covering the story sits on the other side of the room. (That has at times caused the paper to lose out to other outlets: “The most embarrassing thing was when the Seattle Times scooped us on a story our advocacy department was involved in,” Ashley Archibald, a former Real Change writer, said. “I had no clue.”)

Still, as one of about a hundred “street papers” around the world that fuse journalism, employment, and activism, Real Change tends to support the nonprofit’s overall mission. “A special vantage point for a Real Change reporter is when we’re asking about homelessness,” Nacozy told me. “We’re really clear. We advocate for these people in particular.” But if, at its founding, in 1994, the newspaper had a unique grasp of the housing crisis, most media have since been forced to confront the problem. “Homelessness”—by which people usually mean the eyesore of tent dwellers rather than mass displacement accelerated by the spread of Amazon and other tech giants—is now the central political concern in Seattle. Every newsroom in the city has made the subject a daily focus—often following Real Change’s lead while crowding its niche.

In the spring of 2021, when George was reporting on Bitter Lake, three-quarters of adult Seattleites were receiving coronavirus vaccines, and Real Change was attempting to reopen its office and newsroom, just across the street from a Christian charity. The pandemic had meant a dramatic loss in circulation, vendors, and staff; the next few months would be critical, for both the publication and the city. Residents were busy fighting over “Compassion Seattle,” an amendment to the city charter that promised to keep the streets “open and clear of encampments.” Kshama Sawant, a socialist council member and Real Change ally known for her “tax Amazon” campaign, was expected to face a recall. And Seattle was looking toward November, when it would elect several council members and a new mayor to replace Jenny Durkan—whose policies have been criticized frequently in the pages of Real Change. (“Homeless sweeps under Mayor Durkan have mostly increased the stress on unsheltered people and made them less likely to accept help,” a piece read.) Real Change planned to cover these stories with earned empathy—and to set an example for other newsrooms.

“Nobody’s actually talking to people living in the encampment.”

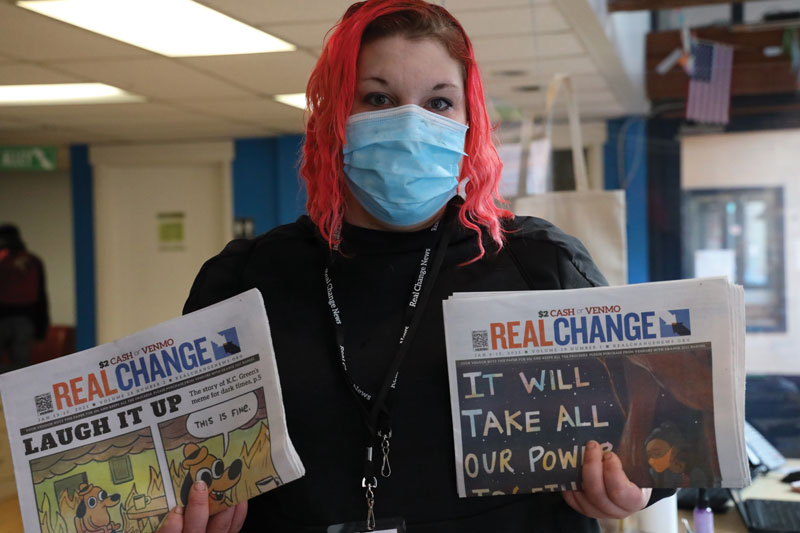

Trinity Holabach with copies of Real Change. Credit: Ace Azul

Zackary Tutwiler is a vendor in Seattle. Credit: Jonathan Vanderweit

Real Change is a Seattle institution, but it was conceived in the late eighties by Tim Harris, a young Marxist convert in Boston. In those days, Harris was struggling with a basic contradiction. As he recruited homeless people to stage sit-ins at the state capitol and to join tent-city protests, “what I saw was that social-justice, economic-justice organizing has a very long timeline and is very uncertain,” he recalled. “Yet, at the same time, people’s needs were very immediate and dire.” He wondered if there might be a way to mix politics and service.

In New York City, in 1989, Hutchinson Persons, a rock musician with an activist streak, began to publish Street News, a paper sold by unhoused and low-income people. A similar tabloid called Street Sheet started up in San Francisco. Harris had founded an anarchist monthly in college and was intrigued by the vocational sales model of these emerging papers. He decided to establish one in Boston, which he called Spare Change and declared to be “Alinskyist” in form (after Saul Alinsky, the Chicago radical), meaning that “homeless people needed to make all the decisions.” Eventually, he joked, the proletariat kicked him out. He looked for a new place that would benefit from a similar outfit.

He chose Seattle but decided, this time, to operate “along more cross-class lines,” appointing himself founding director and installing a traditional infrastructure of staff and board. Then, as now, Seattle had a visible homelessness crisis. Activists were taking over empty properties; a group called share (the Seattle Housing and Resource Effort) was building protest encampments; wheel (the Women’s Housing and Equality Enhancement League) was founded to advocate for unhoused women; homeless artists were running the Street Life art gallery. One day, an artist named Wes Browning was at Street Life when Harris walked in to solicit paintings and illustrations for his new paper. As Browning recalled, Harris was wearing a suit. “I thought he was the FBI,” Browning said. (Harris denied that he wore a suit but said that he did have an uncharacteristically “straight haircut.”)

Harris persuaded Browning to contribute to Real Change. Browning’s cover design for the first issue, in August 1994, was an abstract geometric face rendered in bands of black and white, an octopus tentacle swirling around the chin and cheek. In the years since, Browning and his wife, Anitra Freeman, whom he also met at the gallery, have played every imaginable role at Real Change, while living housed and unhoused. Browning has provided artwork and written a regular humor column; he’s now employed at Real Change part-time, managing the paper’s circulation. Freeman has organized political actions, taught writing workshops, and contributed poetry and essays; she currently sits on the board. In 1997, with Harris, they attended the first conference of a regional street paper organization.

Israel Bayer, who runs what is now the International Network of Street Papers (INSP) North America, is an alumnus of Real Change, Portland’s Street Roots, and Colorado’s Denver Voice; he has also lived through poverty and addiction. When he moved to the Pacific Northwest from Illinois, in 1999, “the anti-globalization movement was rockin’,” he recalled. “There was something in the air that made it feel like something was happening around movements and social change.” Street papers in cities like Seattle and Portland were initially more about community organizing than journalism, he said, but they have since “evolved to be a more polished platform.” The INSP counts more than a hundred street papers around the world, in thirty-five countries and twenty-five languages. Most are monthlies, glossy in style, often with deceptively banal cover stories: on Dolly Parton, Taylor Swift, the Dalai Lama. “Part of that is trying to attract apolitical people to the paper, to a harder-hitting investigative piece on public housing or marijuana or foster care or child homelessness in the schools,” Bayer said. “We’re trying to bring people in.”

In its early years, Real Change had the feel of a newsletter. Issue One began with an essay, “Musings of the Fortunate,” by George Woodring, who’d been nomadic and homeless for many years before getting an apartment through the federal government. “For those readers who have not experienced the dilemma of homelessness,” he wrote, “I ask you for a moment to visualize this: You leave your job after a tiring day, and return to find an empty lot, overgrown with weeds, where your lovely house once stood.” A few years later, as protesters prepared to disrupt the Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization in November of 1999, the cover of Real Change read “WTO in Seattle: No Day at the Beach”; the paper offered a guide to the proceedings. Many issues featured well-known artists: the author Sherman Alexie, the singer Pete Seeger, the actor and writer Sandra Tsing Loh; all included national and global news briefs, editorials on social services, and updates on local housing policy. In time, dozens of vendors made their living by selling Real Change, and the organization became a political force for poor and unhoused Seattleites. The budget now exceeds a million dollars per year, funded through newspaper sales, foundation grants, and individual donations.

As it grew, Real Change aspired to become a significant community news outlet. In 2004, Harris hired two veteran journalists, Rosette Royale and Cydney Gillis, and within a few years they were publishing stories with remarkable impact. In 2007, after Gillis wrote at length about an economic development plan that threatened to use eminent domain to displace a historically Black and Southeast Asian neighborhood, residents fought back, and the plan was canceled. After the Great Recession, and during Occupy Wall Street, Real Change ran pieces on the foreclosure economy, student debt, and racism in Occupy organizing. And even as Real Change evolved from a subcultural “homeless newspaper” to a professional newsroom, it stayed attuned to the lives of the poor. Anne Jaworski, a volunteer with Real Change, told me that she reads the paper because of its “focus on cuts to social services programs—things that wouldn’t be covered elsewhere.”

Today, Real Change publishes a twelve-page weekly in print and online. Though it lacks the resources to compete with major news outlets, it draws on the INSP’s wire service (which sources from street papers around the world), makes use of grants for the occasional investigative series, and collaborates with partners—from the South Seattle Emerald, which covers Black and other communities of color in hot spots of gentrification; from the Asian-American International Examiner; and from Publicola, Erica C. Barnett’s alt-weekly-style blog. (Real Change pays freelancers, but not much; it has an “equity fund” for writers and artists of color.) Like other street papers, Real Change is constantly reevaluating its place in local media. “We don’t have the structure for breaking news,” Joanne Zuhl, the outgoing editor of Street Roots, in Portland, explained. “So we’d rather look at an issue and talk to the people it will actually impact, the people on the receiving end of this policy.”

“There’s the old axiom that journalism is meant to speak truth to power,” Marcus Green, the editor of the South Seattle Emerald, told me. “That’s true, but it’s also meant to remind people who’ve been told they’re powerless that they’re not.” The readers of community news, he said, want to know “how you are able to survive and hold on in a city that no longer appears to be accommodating you.”

Given the rise in extreme inequality across the US, traditional political and business reporting are due for an overhaul.

The stakes of homelessness policy became apparent to Seattleites in 2015, when Ed Murray, who was then the mayor, declared a state of emergency over housing, following the example of Portland, Los Angeles, and Hawai‘i. A few months later, after fatal shootings at “The Jungle,” a tent city along Interstate 5, Murray ordered the site to be cleared, displacing dozens of people. Around the same time, Amazon planted a thicket of steel high-rises downtown and brought on tens of thousands of tech workers. Soon, the city saw record-breaking home prices, displacement, and street homelessness. Yet Murray called Amazon’s hiring frenzy “a great problem to have.”

By the summer of 2018, journalists in Seattle were connecting the dots and had decided to cooperate on an official “day of homelessness.” Four outlets—Crosscut/KCTS 9, a nonprofit digital newsroom and public TV station; KUOW public radio; Seattlepi.com; and the Seattle Times—shared data and coordinated #SeaHomeless reporting; the Seattle Times subsequently created a Project Homeless team. “The idea was, ‘We need to elevate this issue—we’re going to do this to bring it to politicians’ attention,’ ” David Kroman, a reporter at Crosscut, told me. “Real Change had been doing it this whole time, so it felt like the larger media landscape was catching up to them.”

Ashley Archibald was the primary reporter for Real Change at the time. She broke several important stories, including one on a street-outreach group that cut ties with Seattle police because of how officers carried out sweeps and pushed people into emergency shelters. She also wrote about how Amazon and other businesses were likely to use loopholes to circumvent a proposed progressive tax. “Any scoops I got were almost certainly due to the fact that Real Change is very close to the ground,” Archibald said.

But the implications of this proximity were understood differently throughout the office. As “the homelessness problem” became increasingly equated with sweeps, young employees clashed with Harris, who turns sixty-one at the end of September and viewed sweeps as a compromise in the trade-off for shelter. “The way I put this is, I’m not for people’s right to live in squalor,” he told me. His colleagues were vocal in their disagreement; Real Change published op-eds by local activists opposing street evictions without exception. “There were serious tensions between the old-guard homeless-advocacy community that was about expanding services and finding a middle path, and the harder socialist left that was represented by people like Kshama Sawant,” he said.

According to Harris, the debate over the Compassion Seattle amendment has been the latest proof of a polarized community. Business groups and social services agencies behind the proposal argued that it would bake a minimum level of homelessness funding into the city budget and create two thousand emergency housing units. Their opponents, rallied in large part by Real Change’s advocacy department, called the amendment an unfunded mandate to encourage sweeps and prioritize shelter beds over permanent, affordable housing. “I am absolutely in agreement with Real Change that we are opposing Compassion Seattle,” Sawant told me. “It is not compassionate at all.” (She made the same point in an op-ed in The Stranger, noting that the amendment was funded by real estate money.)

Harris, a supporter of Compassion Seattle, found himself awkwardly in league with Tim Burgess, a former city council member who, in heavily left Seattle, counts as a conservative. Back in 2010, Harris and Real Change went to war with Burgess over an ordinance that was widely perceived as criminalizing panhandling—and won a mayoral veto. (Real Change was “almost always pretty harsh on me, both the editorial and the news side,” Burgess said. Nevertheless, he added, “I read it, and people in my office read it, because it offered a perspective that in some ways was closer to the ground.”) By last fall, Harris, feeling out of place at Real Change, decided to step down. (He told me that in November he plans to launch a new regional street paper called Dignity City.)

Real Change continued apace. In late May, as Compassion Seattle advocates were finalizing the language of the amendment, Tiffani McCoy and Jacob Schear, of Real Change’s advocacy department, helped organize a press conference in Victor Steinbrueck Park, next to a memorial for unhoused people. Speakers announced the formation of House Our Neighbors!, a coalition to fight Compassion Seattle and its “pro-sweeps agenda.” Burgess told me that McCoy “engaged in a significant disinformation campaign” about Compassion Seattle, but McCoy and House Our Neighbors! say that they merely pulled subtext to the surface. The amendment “deceptively co-opted the language of social justice and ‘compassion,’ ” McCoy, Schear, and a vendor named Paige Owens wrote in a Real Change op-ed, in June. In late August, after more aggressive campaigning, a state judge pulled Compassion Seattle from the fall ballot, ruling that it conflicted with state law. McCoy told me: “What I love about organizing with vendors the absolute most is they can see through bullshit.”

Where does Amazon end and the housing crisis begin? Seattle is growing faster than any other large city in the United States, thanks to the ever-expanding tech economy. Last year, the median home sale price in the surrounding county topped $820,000; twelve thousand people were counted as homeless. To clean up its reputation as gentrifier par excellence, Amazon has started funding programs to confront homelessness. In 2016, it pledged a year’s use of a former hotel to Mary’s Place, a women’s shelter in Seattle. Later, the company promised to give Mary’s Place $100 million over ten years and allowed it to open a shelter on Amazon’s downtown campus. When the new facility scheduled a ribbon-cutting ceremony, in the spring of 2020, Nacozy had to decide whether Real Change should cover the event. Though the paper had no intention of doing public relations for Jeff Bezos, she said, neither did it “want to become the bulldog against Amazon.” Ultimately, Real Change decided against a story—sometimes, they figured, no coverage is preferable to a dutiful report.

As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, Real Change cannot endorse candidates in elections, but it can take positions on ballot measures and campaigns, as well as on the behavior of companies, and over the past few years the newspaper has devoted many column inches to the extended opera of the Seattle City Council’s attempt to tax Amazon and other big businesses. In 2020, covid-19 and Black Lives Matter consumed much of the staff’s energy; this year, Amazon returned as a major plotline. Real Change ran an article on local protests in solidarity with workers at a warehouse in Alabama, as well as op-eds decrying Amazon for “interfering with union organizing” and linking the company to the “right-wing recall campaign” against Council Member Sawant. In July, Real Change ran a special Amazon issue, pegged to Bezos’s journey into outer space. The cover illustration portrays him as a cyborg puppeteer steering the movements of faceless laborers.

Samira George told me that she hopes to report more on Big Tech in the future, since Amazon is implicitly part of most housing stories. “The biggest thing that comes up with my sources is the shortage of affordability and how prices are going up,” she said. “Obviously it’s connected to tech jobs.” Reporters at the Seattle Times could be trusted to get “the big Amazon stories or the big shelter stories,” she explained, but it was her responsibility to show how “the smaller ones interconnect, giving more of a voice to people experiencing homelessness.”

All journalism could benefit from taking the street-paper approach, which centers unhoused people rather than, say, Amazon executives. Given the rise in extreme inequality across the US, traditional political and business reporting are due for an overhaul; how else to give an honest accounting of our monopoly economy—and of the people deliberately left behind? Katherine Anne Long, the Amazon beat reporter for the Seattle Times, told me that she tries to focus on human stories that reveal “the social impact of business.” Still, she must keep her readership in mind. “I want to tell stories that feel important to Amazon’s headquarters employees who are in Seattle,” she said. “Those roughly sixty thousand folks constitute a core audience for us.”

Real Change vendors also sell to tech workers, but most customers are older, longer-term residents with a charitable bent. “We’re lucky, in that people come to us who are benevolent toward someone selling a street paper,” Nacozy told me. “So there’s an expectation that there’s an anti-poverty instinct.” The paper assumes “a different starting place,” she said: whereas a mainstream outlet might treat homelessness as a “dollar centric” business or real estate story to satisfy its audience, Real Change would always make it a “human rights issue.”

In certain neighborhoods of Seattle, outside upscale groceries, bookstores, and coffee shops, it used to be difficult not to run into a Real Change vendor. The most experienced, high-volume vendors enjoyed fixed locations and shifts; they would sit or stand with a stack of papers, yelling out their favorite page numbers and asking after the families of regular customers. During the pandemic, the number of vendors dropped by a third, to just under two hundred, and circulation shrank from more than ten thousand per week to fewer than six thousand. Customers were encouraged to read the paper online and send money by Venmo to individual vendors. But by the early summer of 2021, people were stepping out again; week by week, the printing load was increasing.

On a cool, breezy Friday on Seattle’s Third Avenue, men zipped in and out of their tents in a dance of avoidance and symbiosis with neon-shirted garbagemen hired by the downtown business improvement district. James Smith stood outside a corner Starbucks, wearing a baseball cap, nylon jacket, and jeans, a Real Change badge hanging from his neck and several newspapers under his arm. He told me that he had come to Seattle thirteen years ago but just recently learned about Real Change. He kept running into a friend who sold the paper. “I decided, I said, ‘I’m gonna check it out.’ ” Smith went through a short orientation, agreed to follow a few basic rules, and received ten free newspapers to try his luck. No other job requires so little of its workers from the start. (“You don’t need to have an ID or even use your real name,” Camilla Walter, Real Change’s development director, told me. “You just have to be over the age of eighteen.”) Smith, who was staying at a Compass Housing Alliance shelter, had made a couple hundred dollars so far. “This has helped me immensely,” he said. “I’m on hard times, with the pandemic and what’s going on.”

Harris and Bayer speak of street papers’ equalizing plane of commerce, and there are plenty of touching stories from Real Change staff—of customers who invite their vendor to Thanksgiving dinner or bring them on family vacations, who pool funds to buy their vendor a van or help them get into permanent housing. Many contacts are less pleasant, though. Some people cross the street to avoid Real Change vendors or pretend to have already bought an issue that just came off the printer’s van.

A 2007 study of Street Sheet vendors in San Francisco described sellers’ efforts to “construct an ‘authentic’ homeless identity that meets the expectations of passersby.” Other vendors may go in the opposite direction, assuming the mantle of entrepreneur: a respectable small-businessperson distanced from the life of the street. Real Change does not give vendors a script, and Rebecca Marriott, who leads the vendor program, told me that the roster ranges from people who are street homeless, living in vehicles or tents, to those living in apartments and working other jobs. Before coming to Real Change, she’d helped poor people in New York City find employment and become independent; she observed that homeless services were often unduly separated from advocacy around labor. “When programming is being developed, employment is never mentioned,” she said. “Traditional employment just doesn’t work for everybody, but that doesn’t mean that people can’t work.”

That day, from her covid-Plexiglas-ringed desk on the first floor of the Real Change office, Marriott buzzed people through a secure door and greeted nearly all of them by name. A vendor named Priscilla came in, carrying a large backpack and wearing a wool coat that drew compliments. “Rebecca got it for me!” she said. (Marriott had set the coat aside from the donations closet.) Another vendor entered, and yelled an off-season “Merry Christmas!” Before March of 2020, the storefront was usually crowded with vendors buying papers at Real Change’s cashier stall, taking coffee and bathroom breaks, charging their phones, and doing research on office computers. In pandemic mode, only a few visitors were allowed in at a time. Many asked Marriott or Ainsley Meyer, a case manager, for grocery bundles, dry socks, hygiene kits, sack lunches, or coats. Eventually, across the street, a mobile health unit started offering covid vaccines, which Real Change encouraged its vendors to get with the promise of twenty-five free newspapers per shot. Meyer also helped vendors apply for housing, food stamps, and pandemic stimulus checks.

Though vendors aren’t required to join the editorial or advocacy sides of Real Change, many choose to do so. Some have offered feedback at weekly editorial meetings with Nacozy; others tell Marriott and Meyer what they think about cover stories: that a given headline is too depressing (not so marketable) or that a color scheme repeats that of a previous issue (not novel enough to claim the attention of passersby). Vendors contribute story ideas, too. In April, Neal Lampi, a former organizer with Real Change who lives in an RV, supplied a tip: The city intended to reinstate a seventy-two-hour limit on parking, which had been suspended during the pandemic. People living in their cars or camper vans would have to resume their hunt for the next safe space and give up the community they’d formed with neighbors parked nearby. Based on Lampi’s lead, George wrote a profile of Dee Powers, a thirty-eight-year-old who’d begun living in an RV in 2015, when their rent shot up by 40 percent. The advocacy department took up the matter with city hall, and Sawant called on Mayor Durkan to lift the limit—but to no avail, even as the city and state effectively extended a pandemic ban on evictions.

Last summer, as covid deaths spiked and protests flared in response to the murder of George Floyd, Lampi reflected on vending and politics in an essay in Real Change. “You never really know what motivates people to buy a paper,” he wrote, but “even a $2 customer could be seen as a witness to those standing in solidarity with the poor, the homeless, LGBTQ rights activists, #BLACKLIVESMATTER, immigrants and all of the legions of villainized people paraded across the screen of Faux News.” Yet at the same time, he continued, the great thing about selling the paper “is that virtually anyone” can do it: “We don’t demand adherence to a creed or agreement with our editorial viewpoints. You can thrive simply by treating others like you would like to be treated, selling a boat load of papers, happily voting Republican.”

This story was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, a journalism nonprofit.

E. Tammy Kim is a freelance reporter and essayist whose writing has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Review of Books, the New York Times, and many other publications. She coedited 2016’s Punk Ethnography.