A great interview is one of the journalist’s most powerful tools. It can be informative, entertaining, thoughtful. For the next five weeks, the Columbia Journalism Review and MaximumFun.org will broadcast conversations with some of the world’s greatest interviewers. Hosted by NPR’s Jesse Thorn, the podcast, called The Turnaround, will examine the science and art of journalism.

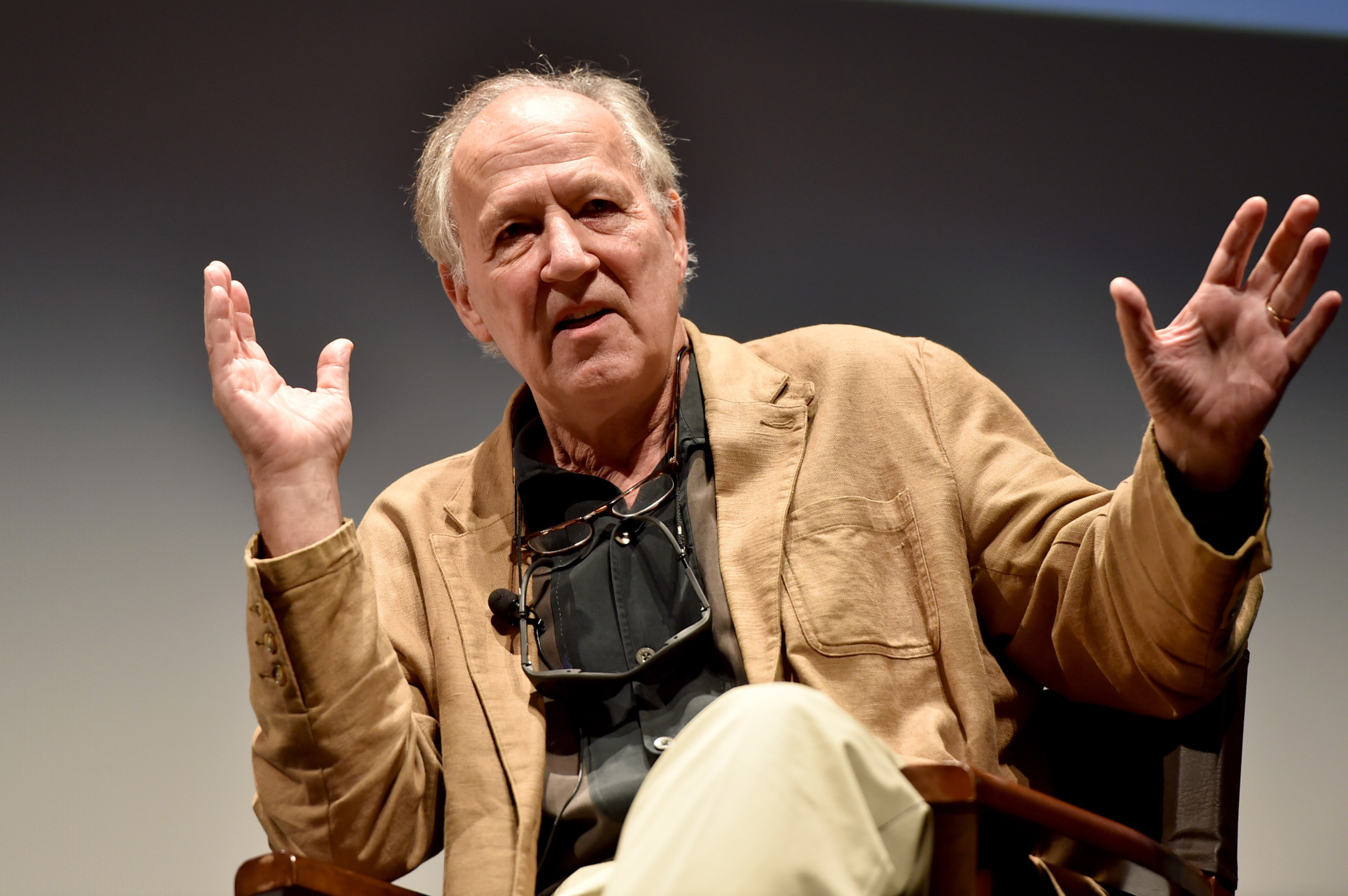

This episode features Werner Herzog, German screenwriter and filmmaker. An edited transcript is below.

PEOPLE V. NATURE

Jesse Thorn: Many of your documentaries are about the natural world and you can go and point a camera at them, and we hear you talk. But when you’re making a documentary about people, are you always comfortable with the part of that that is basically bothering them?

Werner Herzog: Sure I do. I’ve heard it once in awhile that documentary filmmakers should be just like a fly on the wall. Wrong. We are filmmakers, we are creators. We shape things, and we shape movies. I kept saying to those people, “No we should be the hornets that go out and sting.” If you have, let’s say, it’s the only camera – the security camera in a bank, and you wait for 15 years and not a single robber is even arriving. Even if a bank robbery occurs, from a little camera on the wall, it would look totally boring. So we are creating, and of course we are, in a way, invasive. We are showing certain angles and perspectives of human beings in front of your camera. A good example is, for example, death row inmates. One of them, Michael Perry, was executed only eight days after I filmed with him. I said to him “Your last appeal for clemency has a lot of elements in it with which I can sympathize, and, of course, you had a very bad childhood but it doesn’t exonerate you.” Then I say, point blank, to him, “All this does not necessarily mean that I have to like you.” And for a moment he freezes, and he says, “Okay,” because nobody has ever spoken like this to him, a man who is going to die in eight days. “And it does not necessarily mean that I have to like you.” He looks like a young kid, when you see the film Into the Abyss. When you see this young man who committed his crimes when he was 18, ten years later, at 28, he still looks like a very nice kid, a real nice kid. When I see him approaching in this little cubicle behind bulletproof glass, there was this kind of gasp inside of me. I have never seen a man as dangerous as him. I have been in very dangerous situations, and I have met very, very dangerous people. Never anyone like him. And yet I’m completely fair and completely open with him, and they notice. They sense it.

Jesse: Is that difficult?

Werner: No, that’s my nature. I know that he has his voice now. Of course, he knew that my film was not going to be his platform to prove his innocence (that happens sometimes in this type of movie), and he said, “Yes, fine. Let’s talk about what whatever is fascinating for you.”

Jesse: What did you find fascinating about it?

Werner: Well it’s a complex case with two perpetrators, three murder victims, four crime scenes, a shoot-out with police, and so… Looking into a human abyss, so deep that you get vertigo.

TRENDING: What tabloid reporting for the New York Post taught me about journalism

INTO THE ABYSS

Jesse: Do you feel comfortable talking to someone in that situation when you are revealing something that significant, that is often closely held and personal?

Werner: Well, that’s my profession. I have to take an audience through my camera very deep into the heart of men or women, and that’s what I do. There’s nothing uncomfortable because Dieter Dengler really wanted to show me what he had under his floorboards in his kitchen, and he was proud to show me. Sometimes you see things are stylized. The very first scene he comes in is 1949 Buick, a beautiful old car, and he steps out and opens and closes the door, opens and closes, and he enters his home but before he enters opens, closes, opens, closes. Then he’s inside. From inside, he opens and closes and then he sticks his head out and he says, “It may sound odd – it may look odd that I’m opening and closing doors but that means freedom for me, that I can do that.” It was a stylized, staged scene because when you come into his home, and I show it briefly. There is this small entrance hall, and there are seven or eight paintings. I said to him, “Dieter, you have a lot of open doors here. Half-opened doors.” He said, “Really, really? Let me look.” And I said, “Why did you buy it?” “Oh yeah, I bought it because it was a bargain. It was only 10 bucks a piece.” So he didn’t even notice, and then he said to me, “You know what? Maybe deep inside of me I bought these images because freedom is being able to open and close a door. That’s what it means for me.” I said, “Dieter, let’s just get out here and do a scene where you open and close doors.” And he said to me “Doesn’t it look funny?” I said, “Even if it looks funny, we’ll understand you.” In this case, of course, I do modify facts in such a way that they resemble truth more than reality. Some people say, “Ah yeah, this is all manipulation, and you are lying to us.” Nonsense.

Jesse: How do you invoke that truth when you are talking to a real person like Dieter Dengler standing right in front of you?

Werner: I told him exactly why I would like to do it, and he looked at me and pondered for a moment, and he said, “I got you. I got it. Let’s go and do it.”

ASKING QUESTIONS

Jesse: When you walk up to somebody and say “Can I talk to you on camera?” in whatever the particular context is, how do you do it?

Werner: I rely on my experience in life, and I can read the heart. I do understand the heart of men, and I would be capable to do a conversation completely unprepared. I’m not a journalist with a catalog of questions. You throw me anywhere with anyone, and I can make a meaningful conversation.

Jesse: Why do you think that is?

Werner: Because I do read much more than watching films. So my ability of storytelling, my ability of poetry, my ability of conceptual thinking is very keen.

Jesse: It seems like one of the things that helps you in these situations is that your interest is sincere, and it reads as sincere. You really want to know the answers to the questions that you’re asking.

Werner: Sometimes you can’t get them, and I know in advance. For example, in “Lo and Behold,” the Internet film, I’m asking my, as I call it, the Clausewitz question. Clausewitz was a war theoretician, in Napoleonic times, Prussian, and he wrote one of the finest books on warfare. He strangely and famously once said, “Sometimes war dreams of itself.” It’s a stunning statement. I extended the question, and I said, “This was what Clausewitz said about the war. Does the Internet dream of itself?” Of course, it’s a stunning question, and you know whoever is in front of you, a scientist, or a neurologist, or whatever, they wouldn’t give you a full answer. Nobody knows.

Jesse: Now a lot of people who are on camera in a Werner Herzog film, they know that Werner Herzog is going to ask them a real big question like that, and they know that they’re just going to try and answer it as best they can. Right?

Werner: Yes.

Jesse: That’s a lot of people. There must be people, though, who are faced with a question like that and they go, “Pffth, I don’t know, whatever. Fuck you, Werner Herzog.”

Werner: No, I wouldn’t ask this question to someone who appears to be shallow. I ask the question to the right people, and I know who the ones would be.

Jesse: Do you often get responses that you’re not expecting?

Werner: Of course, and that’s the beauty of real deep conversation.

Jesse: Are there questions that you’re afraid to ask?-

Werner: Not really. I wouldn’t ask certain questions if somebody is deeply hurt because of certain events in his or her life. I would not poke into that. If something of that comes to light, fine. But I would not try to squeeze it out of anyone.

ICYMI: A hidden message in memo justifying Comey’s firing

ON SITCOMS AND BASEBALL

Jesse: Do you watch any sitcoms?

Werner: No, I barely know what it is. I think it’s people sitting on couches and talking. Sometimes when I zap through channels, I see people talking in their kitchen or in their living room. I really know very little about it.

Jesse: What’s your favorite unimportant thing to do?

Werner: That’s a much deeper question.

Jesse: I like to watch baseball, Werner. What I like about baseball is I have a very sophisticated understanding of it, and there is a sophisticated understanding of it to be had, but it is also a little bit boring, and it does not matter at all.

Werner: I do understand the basic rules, and I do understand the basic suspense in it. That there’s one guy with a bat, and the entire field is against him, and they try to to get him out as fast as it gets. Every single pitch at him is a certain form of suspense. I do understand that part. For me, it would be watching soccer because I played it myself. I like to watch games where I see players that can read the game, and that’s something very unique, very special. Very few players in the world have this ability, to read spatial movements and read what’s coming at them.

The Turnaround is available on MaximumFun.org. You can also subscribe on Apple Podcasts to get new episodes as they become available.

Photo credit: Alberto E. Rodriguez/WireImage

The Editors are the staffers of the Columbia Journalism Review.