It was unseasonably warm the day Joshua Beal, a twenty-five-year-old Black man from Indianapolis, was killed by a white police officer in Chicago. Beal was in town to attend a cousin’s funeral. Around three o’clock in the afternoon of November 5, 2016, a long procession of mourners lined up their cars at the exit of Mount Hope Cemetery and spilled out into the neighborhood of Mount Greenwood, in the city’s southwest corner. Mount Greenwood is home to many of Chicago’s police officers and firefighters; nearly 85 percent of its residents are white, in a city where people of color make up the majority. The ensuing altercation—between a family of Black mourners and two off-duty cops—would trigger pressure points familiar to Chicago, and to the rest of the country.

By the official police account—and the media retellings that echoed it—the killing resulted from a bad bout of road rage. On 111th Street, near South Troy Avenue, an off-duty firefighter called out from his car window to a member of the funeral procession: they were blocking a fire lane. Both drivers got out of their cars and began to argue. The argument escalated. According to a postmortem examination report, Beal, a passenger in a Dodge Charger, retrieved a firearm from the Dodge. An off-duty police officer, later identified as Joseph Treacy, was at a business nearby and, per the examination and press accounts, aimed to break up the altercation and got caught in the fray.

There were numerous witnesses. In all, thirty-two calls were made to 911 as Beal’s family struggled to de-escalate the situation. Soon, Thomas Derouin, a police sergeant from the 22nd Precinct who happened to be driving by, stopped and, according to the Chicago Police Department, announced that he was an officer. He yelled, the report stated, attempting to intervene. Then he noticed that Beal was holding a gun. “Beal fired at the Off-Duty Sergeant one time,” according to the examination report. Derouin, “in fear of his life,” returned fire, discharging his weapon seven times. Beal collapsed. He was taken to Advocate Christ Medical Center and pronounced dead at 3:44pm.

As news of the shooting spread, a familiar police narrative began to take shape in the press. Articles said that the officers, despite being off duty, were in full uniform. The implication was that the cops involved were justified in shooting Beal because it was clear they were cops, and because Beal chose not to lower his weapon. The examination report, filed at 10:53pm the night Beal died, stated that Derouin “was in full uniform on his way to work.” Anthony Guglielmi, the senior spokesman for the Chicago police, repeated this detail to reporters at the Chicago Tribune, the local CBS affiliate, and other outlets.

The Beal family’s account sharply contradicted the police narrative. (Some articles included their version of events, or said that the family rejected the police explanation, but most prioritized the official account.) Beal’s sister, Cordney Boxley, told local reporters that a cop in an unmarked car cut off both her and a seventeen-year-old girl also driving in the funeral procession and later pushed another family member to the ground, pointing a gun at her. The family insisted that it was never clear that the men who had arrived on the scene were law enforcement—a claim supported by the 911 calls, which would be released to the public months later. Eyewitness videos would also surface, depicting a crowd of people jostling noisily to break up a tense argument, as well as loud music playing from a nearby car; there’s lots of chaos and little clarity.

Only a year earlier, Chicagoans had erupted in protest after the release of footage depicting the killing of Laquan McDonald, a Black teenager, by a white cop. For months, the police department had insisted that the officer’s shooting of McDonald was justified, because McDonald had been holding a knife and lunged at police; witnesses disputed that account, and it took a judge’s order, in a lawsuit brought by an investigative journalist, to make public the video that proved the police were lying. McDonald had never lunged at the officers; in fact, he had begun to walk away. When Beal was killed—and, once again, the family’s story diverged from the police account—the city experienced a tragic sense of déjà vu.

It was not the first time that a white cop had shot and killed a Black man, nor the first time that police officers had described it in ways that contradicted witness accounts. The very concept of a “justified” killing—in police terminology, a “good shoot”—betrays the paradox inherent in police communications: A police department exists to protect the public and to protect itself, but can it ever really do both? In relaying information about a crime in which an officer may have been at fault, brand management becomes a priority. Victims—who more often than not are Black—have long listened to police with skepticism, expecting misinformation about themselves and their communities. Journalists have struggled to tell the whole story.

Modern American police departments emerged in the 1830s out of a desire to control “disorder” in growing cities, starting with Boston. New York City followed, then Albany, and then Chicago, in 1851. Police officers were offered steady, full-time employment supported by public funds, and had a broad mandate to define what “disorder” meant—drunk people in the street, prostitution, hooliganism—in the interest of protecting the citizenry. According to Gary Potter, a crime historian at Eastern Kentucky University, “Early American police departments shared two primary characteristics: they were notoriously corrupt and flagrantly brutal.” They were also valorized by American culture, including in the mainstream press. Crime stories provided great hero’s tales and horror dramas to sell papers.

A police department exists to protect the public and to protect itself, but can it ever really do both?

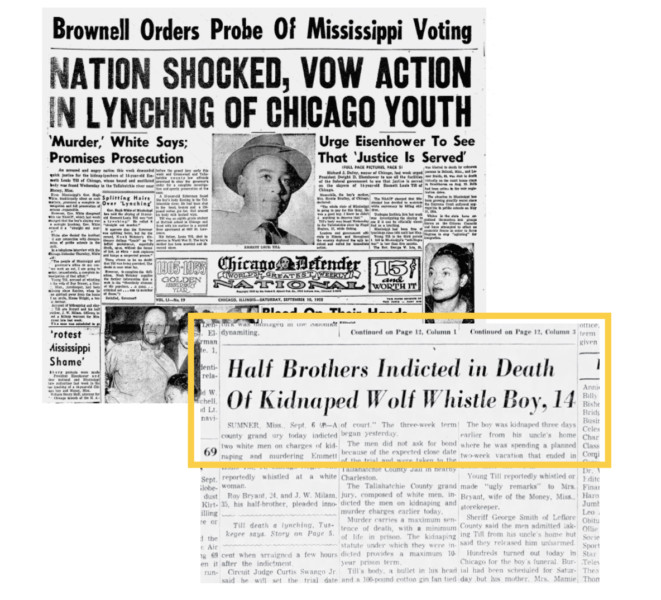

In the eyes of people from marginalized communities, the press was an ally of police officers who enforced white supremacy. In 1955, for instance, when Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old boy from Chicago, was beaten and shot to death by white men in Mississippi, news outlets in the South presented Till’s killers sympathetically and focused on Till’s alleged infraction—whistling at a white woman while shopping for candy—rather than the investigation into his abduction and murder. The New Orleans Times-Picayune featured quotes from police officials who cast doubt on whether the disfigured Black body pulled from a river was actually Till’s. A headline in the Atlanta Constitution referred to him as the “Wolf Whistle Boy” in its coverage of the trial. The Jackson Daily News quoted the unverified theory of a local sheriff: “The whole thing looks like a deal made up by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.”

The Black press, read widely among African Americans but virtually ignored by white people, took a different tone. The Chicago Defender ran headlines that referred to Till as a martyr. Black newspapers like the New York Amsterdam News and the Atlanta Daily World described Till’s injuries in greater, more graphic detail than was typical in white newspapers. A headline in The Crisis described the tragedy as “Mississippi Barbarism.” But in the days of state-sanctioned racial apartheid, the reach of these reports was limited, and the dominant narrative was the white one. An all-white jury, having deliberated for just over an hour, declared the killers not guilty—despite the fact that the men had been identified by eyewitnesses and confessed to kidnapping Till. (Last year, the Justice Department said that it had received “new information” about Till’s death, after his accuser admitted that she’d lied.)

The status quo held for generations: to an overwhelming degree, the relationship between cops and reporters was symbiotic. Jim Mulvaney, on the beat in New York City in the seventies and eighties, was born in Hollis, Queens, and the officers he wrote about were, like him, mostly Irish. “So there I was,” he recalled to me, “Jim Mulvaney, in a bar with a couple Irish guys hanging around.” Reporters working the cops beat saw themselves in their subjects—“They were blue-collar types. Jimmy Breslin didn’t go far in college; Pete Hamill did not graduate from high school. They were from working-class families,” Mulvaney said—and in those days, they were given plenty of time and money to cultivate sources. “I would start my morning at Dunkin’ Donuts—would buy three dozen and get three rolls of dimes for pay phones,” Mulvaney recalled. “I would go into the detective squad room, and everyone is like, ‘Where’s the donuts? All right, have a seat, Jimmy.’ ” He had an evening routine, too. “I had an obscene expense account where I could walk into a bar in the early eighties and put a hundred-dollar bill down, and everybody drinks on me, all the cops.”

Conversation flowed, and the narrative that emerged was sympathetic. “In the old days, there was more favor-trading than now,” Mulvaney said. “I would frequently carry wads of Yankees and Rangers tickets.” He was relatable, and he was plugged in. “If you establish a reputation as a stand-up person,” he explained, “you’re more likely to find some cooperation.” Maintaining that reputation generally meant accepting what information cops offered, not challenging it.

When Emmett Till was murdered, Black papers covered the story differently from white ones. Images from the Chicago Defender and the Atlanta Constitution.

Over time, however, the dynamic changed. “With Watergate, the new breed of reporters wanted to be investigative,” Mulvaney said. Journalism began to attract a wider variety of people and its makeup no longer reliably mirrored that of the police force. In the years that followed, violent-crime rates began to drop, and reporters, with fewer shock-and-horror stories to tell, instead unveiled police corruption. In response, police leadership increasingly prioritized reputation; across the country, departments formalized communications. Police sources became more and more likely to direct reporters to public information officers, known as PIOs, or to defer to their commissioner. Reporters could still sometimes call upon sources in police departments, but the opportunities diminished. The shift made it easier for departments to disseminate misinformation that protected cops who abused their power—something that never required online troll farms, only the simple, human technology of false statements, obstruction, and evasion. “While PIOs are nominally in charge of information, it’s really the public relations arm of the police department,” Mulvaney, who is now an adjunct professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, explained. “The job of public relations is advertising, not transparency. It’s improving the image of the department. There’s some stuff they have to divulge, but the main function is to make the cops look good.”

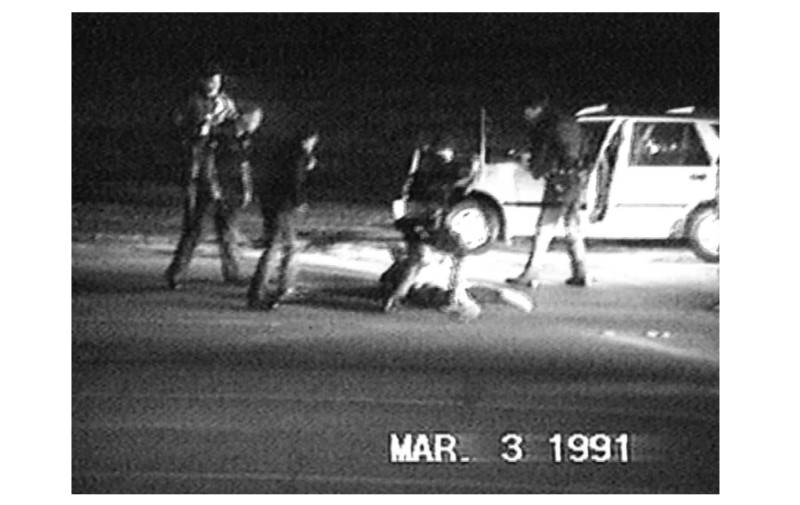

In 1991, when officers from the Los Angeles Police Department violently beat Rodney King, a Black man who had been driving home from a friend’s house, footage taken from a nearby balcony made cops look bad. The owner of the video took it to KTLA, a local news station, after which it was viewed widely. A year later, the officers involved were acquitted, and LA erupted in riots. More than any event prior, the assault on King upended the way police stories were told. The availability of video, and the visible contradictions in police comment about the case, made it impossible for journalists to ignore the dreadful reality at hand.

Since then, reporting budgets and newsroom staffs have declined, which means the press-police dynamic often gets pared down to bare, transactional dialogue, prying for information about the most controversial cases. At the same time, body cameras and social media have provided more alternatives to the official police line. In 2016, a police officer shot and killed a thirty-two-year-old Black man named Philando Castile, a school nutritionist who had been pulled over in his car in Falcon Heights, Minnesota. The incident was captured by a dashboard camera; Castile’s fiancée, Diamond Reynolds, was in the car with her daughter and quickly began streaming video of the aftermath on Facebook Live. Coverage of Castile’s death was able to draw upon non-police accounts as never before; meanwhile, the public’s perception of events was shaped by a narrative other than what police officials wanted to push. In offering a more nuanced, more complex portrait of what makes a “crime” story, journalists were only just beginning to peel away layers that, for years, insulated the police from real press scrutiny.

Cops, for their part, are vexed when reporters seek out information beyond what’s provided. A 1995 encyclopedia of police practices characterizes the Freedom of Information Act as inherently antagonistic, deepening “the rift between police and the media.” The book describes law enforcement’s belief that media is “extremely liberal and permissive” and interested in “zealously” pursuing stories of police corruption because it “almost always garners headlines and television attention.” Joseph E. Scuro Jr., a consultant to police departments, writes, “Part of the problem is that reporters often believe that the police routinely withhold information from them, or worse yet, regularly release inaccurate information. Sometimes this causes a reporter to ‘dig’ for the ‘real’ story when, in fact, there is none.”

Chris Burbank, the vice president of strategic partnerships at the Center for Policing Equity (CPE), a think tank that studies disparities in policing, spent twenty-four years working as a police officer, including nine as the police chief in Salt Lake City. The relationship between police and the media, he says, is crucial on both sides. “Law enforcement is suffering a crisis of legitimacy,” he told me recently. “And in order to gain that legitimacy back, you have to have good third-party validators, because you telling your own story does not work.”

Over time, police departments have done some things to really wear down public trust. We’ve treated people poorly.”

When officers don’t talk, Burbank argues, their silence reinforces a pervasive belief that they don’t, in fact, work chiefly for the public. During his time as police chief in Salt Lake City, he hired a radio host to act as media director of the department—a move that he says was considered controversial, since it was the first time that position had been filled by an outsider rather than a loyal cop. Where police chiefs used to appear in public only on select occasions (to accept an award or to boast about department accomplishments), Burbank went on local media frequently, in an attempt to garner trust with reporters—often to the chagrin of his own officers, who accused him of spending too much time on television. His instruction to his communications staff was to provide “as much truth as you possibly can.” That is, while there may be details that shouldn’t be released to reporters—such as the type of weapon used in a homicide, information only the suspect, still at large, would know—police should explain everything but. “You need to articulate that, not in a ‘no comment,’ but as ‘There are things that we are investigating that we can’t tell you right now. When the point comes, I’ll be happy to tell you,’ ” Burbank said.

In his role at CPE, Burbank travels the country advising police chiefs on research-based reforms, including those that would improve their dealings with the media. Some departments are open to what he has to say, but too many still cling to a preference for silence. “It often takes on the tone of ‘Tell them the bare minimum that you have to and then don’t say anything else,’ ” Burbank said. “I think that’s the wrong thing to do.”

When it comes to cases like the Laquan McDonald shooting, if there’s video evidence that a cop shot a civilian, Burbank tries to persuade cops to be open. “We routinely show bank footage or 7-Eleven footage of a robber coming in, and then we say, ‘Hey, who is this person?’ That doesn’t seem to jeopardize our ability to prosecute a robber,” he’ll tell them. “Why, then, when an officer is involved in a shooting, and there’s film, why does that somehow jeopardize our ability to investigate or conduct a proper prosecution? That’s where it doesn’t make any sense.”

The availability of footage, as in the case of Rodney King, makes visible the contradictions in police comment.

Burbank encourages the use of body cameras, though he argues that footage won’t solve what underlies the trouble with misinformation in crime coverage: competing claims over truth. “I don’t have any problem with the public filming all they want, but it doesn’t provide truth,” he told me. “What it provides is a factual representation. And then you may look at that and say, ‘Boy, that officer was heavy-handed there.’ And I’m going to look at it and say, ‘No, I think he was all right there. I mean, it looked to me like this, and oh, by the way, I think the sky is blue today.’ And you say, ‘No, it was really overcast and gray.’ ” Information is one thing, but judgment can always be up for debate.

Chicago, of course, is not the only city where tensions arise between the press and police. But if the complicated case of Jussie Smollett, early this year, showed anything clearly, it was that there is deep distrust between the Black population of Chicago and the police force, and that from distrust can come confusion, misinformation, and resentment. Guglielmi, the Chicago police spokesman, offered regular updates about the Smollett investigation on Twitter: an Empire star had reportedly been the victim of a hate crime; officers were seeking tips; surveillance footage was found; suspects were identified, interrogated, then released; Smollett was classified as a suspect, and charged; case closed. The story attracted wide fascination and outrage. When it was making headlines, a friend wondered aloud to me, “Why is anyone believing the Chicago police?”

Guglielmi, who has been the CPD’s chief communications officer since June 2015, previously worked in public affairs for the police in Baltimore and led communications for the US Office of Special Counsel. He is tall and clean-shaven, with rectangular black glasses and a pursed-lipped smile. “The media, in my mind, is a vehicle to reach the public,” he told me. His task in Chicago, a city with a long history of mistrust in the police, has been to transform his department into “a fully functional messaging and communications office,” he said. In the past decade, he explained, standards have changed. The way things used to be, “When there was a criminal investigation, you didn’t talk about it until charges were filed.” But in Chicago and elsewhere, that will no longer suffice. “Over time, police departments have done some things to really wear down public trust,” he said. “We’ve treated people poorly.”

Guglielmi began streamlining how media inquiries would be handled, as his team was fielding about three hundred press requests per week. (In Baltimore, the average was closer to ninety per week.) “The first thing we did was set up a process in which information that was coming out to the media would be the same going out to police districts, community meetings, and in face-to-face interactions with officers and residents,” he said. “Everybody is speaking from the same sheet of music, and that was hugely important.” He also hired journalists and videographers to work for the CPD. “What we aim to do is be our own newsroom and storyteller,” he told me.

Guglielmi started his job amid challenging circumstances. The Laquan McDonald case had gripped the city and country; the police department, via its communications team, was refusing to release dashcam footage showing what happened. In February 2015, an independent journalist published McDonald’s autopsy report, detailing injuries that did not match police accounts. At least fifteen Freedom of Information Act requests for the dashcam video were filed; all were turned down because, the department argued, its release would interfere with an internal investigation. By the summer, when Guglielmi arrived, a freelancer was suing the city for the footage, and it came to light that, when the foia requests were denied, there had been no evidence of an active internal investigation.

“Laquan McDonald was a very high-profile, national incident that really tested our trust,” Guglielmi told me. He wouldn’t say why the CPD withheld the video—he didn’t work there when reporters began to request it—but he speculated that the department was trying to avoid interfering with a federal probe into the shooting. “I don’t know if that was the reason why the department didn’t release the video,” he said. “Speaking strictly from a communications perspective, you want to release as much information as possible without hurting the case.”

In court, a judge ruled in favor of releasing the video. On November 24, 2015, Jason Van Dyke, the officer who shot McDonald, was charged with first-degree murder, and hours later the footage was made public, igniting a national uproar. The video was mostly without on-the-scene audio, however, and reporters soon learned that, among the dashcams on the squad cars present, none recorded sound; at least three didn’t work at all. Police told DNAinfo that 80 percent of the department’s dashcam systems failed to record audio due to “operator error or in some cases intentional destruction” by officers. When I followed up about this, Guglielmi told me, “We’ve got body cameras now, on the actual officer. It’s a fail-safe.” In October of this year, a report by Chicago’s inspector general, newly released to the public, revealed that sixteen CPD personnel were involved in covering up the McDonald shooting, including by giving false statements and fabricating details.

Van Dyke was ultimately sentenced to just under seven years in prison; he’d been charged with sixteen counts of aggravated battery with a firearm, one for each shot that tore into McDonald. He was the first on-duty cop to be convicted of murder in nearly half a century. Since then, the CPD has made some adjustments to its communications strategy. Guglielmi installed computer terminals in the newsrooms of all major Chicago outlets to provide real-time information about police activity. After shootings in which officers are involved (what Guglielmi calls “use of force”), he is now consulted about what information can be released to the public and when—a change from the pre-McDonald days. “With Laquan McDonald, the department never updated the public record,” he explained. “That’s what really broke the trust between CPD and the community. I don’t know why that didn’t happen. What I can tell you now is that we built systems to try to make sure that we have a check and balance to the information we put out.”

He went on, “All we have is our work and our trust. And if that is broken, it doesn’t just affect our reputation—that’s not what we care about—it affects our ability to do our job, make the city safer. It’s not about the image.” He also told me, “Every day you come in and look at how you’re conducting business and improve it. You do better.”

Investigative reporters have time to file information requests to the CPD and vet other sources, but those working on daily deadlines rarely get that opportunity—and it’s their stories the public is most likely to read or see on TV. Josh McGhee, who writes for the Chicago Reporter, started his career at DNAinfo, where he filed multiple crime stories per day, often before 9am. “We were talking to the communications team every morning at 6am,” McGhee said. “They would give us basic crime information on shootings. Usually there’s not a lot of statements from the communications team, unless you go directly to the spokesman.” Even when he was skeptical of the police, he was dependent on them. “You have to trust them as a source,” he explained.

Over the years, McGhee came up against obfuscation, omission, and delay. Sometimes, officers would present uncertain information as fact, advancing a certain story line. “You don’t realize how often someone is saying the kid had a knife and they don’t recover the knife, a kid had a weapon and they don’t recover the weapon,” he told me. “How often that changes the narrative.”

For McGhee, McDonald’s death was a turning point. “I would say that I was always wary of stories from police and narratives given from police,” he said. But after the McDonald case, he began asking himself, “How many times did I start the narrative by listening to police officers and printing what was said?” McGhee explained, “It forced me to realize that a lot of the time, if you’re just taking the police side, you’re getting a very one-sided story. How many times are the people who are calling in to a communications department going to go back on the ground and ask witnesses what happened?”

The demands that newsrooms place on crime reporters, particularly those working the daily beat, McGhee argues, make it too tempting to rely solely on police communications officers instead of building sources in neighborhoods where crime happens. “Depending on police sources is the number one way to go down the wrong road,” he told me. “You can go to a crime scene and you can try to be the night crawler and get some kind of information, but is that the appropriate time to figure out what happened? This is a time of fear, this is a time of panic, this is a time of worry. But coming back to these instances and trying to talk to these families, you can piece together a better story of why this incident happened.”

McGhee, who is a twenty-eight-year-old Black man, said that he’s uniquely positioned to do that work in areas beset by crime—much in the same way Mulvaney once was, with cops. “They look like my family, they look like my mom; you’re from around here, you know people from this neighborhood, you know people in these situations even if you don’t know these specific people,” he explained. “I think you can feel that when you’re asking them to tell these stories. You’re asking the right questions empathetically.”

Two days after the death of Joshua Beal, the Chicago Tribune published two videos recorded on a bystander’s cell phone. Screenshots circulated online; protests flooded the streets of Mount Greenwood. In January 2017, an independent review board released 911 calls and additional witness videos.

What emerged changed the nature of the story, Maya Dukmasova, of the Chicago Reader, told me. “The people calling kept saying there was a white guy waving a gun,” she said. “No one who was calling 911 identified that the cop was a cop.” One caller described a white man in a red shirt and jeans. Another reported a man with short hair and a gun. Twelve more callers sought help after shots rang out. Someone characterized the chaos as “a total race thing.”

In the video, “nobody was wearing a uniform,” Dukmasova observed. Derouin, who shot and killed Beal, was wearing blue cargo pants. “I guess they were uniform pants, but they were not immediately identifiable as such,” she said. “He was wearing a White Sox hoodie or zip-up jacket. And he indicated himself, in his paperwork about the incident, that he was in plain clothes.”

In initial press releases and interviews, Guglielmi had insisted that Beal and his family knew that the men who approached them were cops. But when Dukmasova compared press comments to the transcripts, she found that “the public information team was completely disproven by the 911 calls, the video, and the officer’s own report.”

On March 26, 2018, sixteen months after Beal was killed, Dukmasova published a follow-up story, exposing the misinformation in previous coverage. “No one reported the inconsistencies between the Police Department’s prior accounts of Treacy and Derouin’s actions and appearance and the information conveyed by the video, 911 calls, and internal documents,” she wrote. Of Beal’s mother, she added, “Although this incident has since disappeared from the news, the day’s events are a never-ending tragedy.”

When I asked Guglielmi about the conclusions of Dukmasova’s piece, he told me that the frenzy of a crime scene makes it hard to get the facts right. “News is instant; information is instant, it’s demanded in minutes,” he said. “Unfortunately, when you go to a chaotic scene, whether it’s a shooting or a fire or anything that requires great attention to detail and it’s very chaotic, you’re going to get misinformation. You’re dealing with emotion, you’re dealing with chaos.” But aren’t misstatements harmful? “What’s important,” Guglielmi said, “and this was a lesson from Laquan McDonald, is you have to update the record.”

This past June, Chicago’s Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA) cleared Treacy and Derouin of wrongdoing. The official report acknowledged that the situation emanated “from a racially tinged confrontation between people who live in the neighborhood where it occurred and people who were merely driving through it.” Both of the cops involved had received dozens of misconduct complaints that had gone unpunished, including, according to Dukmasova’s reporting, incidents in which racial epithets were used.

As I’ve talked to various reporters and law enforcement officers, I’ve often heard them say that truth is at the root of their work. But to get to the truth, of which there are often many versions, we need access to a basic set of facts. What happened? To whom? By whom? Misinformation, whether by omission or outright lie, whether intentional or not, can confuse those facts and weaponize them. In cases of police brutality, law enforcement still has the upper hand: American culture, including the press, gives cops the benefit of the doubt. We ask what Beal did to cause Derouin to shoot him, not why a police officer would shoot a young man on his way home from a funeral in the midafternoon. Some interpretations of the truth, we have been taught, matter more than others.

And even having the facts can’t save us from injustice. After the officers were sent back to work, the editorial board of the Chicago Sun-Times published a piece in support of the COPA ruling. “Ask yourself what a police officer is supposed to do when an angry young man pulls a gun—and points it—on a busy street on a Saturday afternoon,” the board wrote. The editorial acknowledges the role race played in the initial altercation, describing it as “good ol’ Chicago racism.” It says that an officer was the first to draw his gun and mentions that much of the truth of what happened “will remain forever in dispute.” Still, the board concludes, Treacy and Derouin did as they were trained to do: shoot. “All else—the racial taunts, verbal threats and general stupidity—becomes background noise.” The editorial does not mention that, contrary to the official line of the CPD communications team, neither cop was in uniform.

Alexandria Neason was CJR’s staff writer and Senior Delacorte Fellow. Recently, she became an editor and producer at WNYC’s Radiolab.