The Honolulu Advertiser doesn’t exist anymore, but it used to publish a regular “Health Bureau Statistics” column in its back pages supplied with information from the Hawaii Department of Health detailing births, deaths, and other events. The paper, which began in 1856 as the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, since the end of World War II was merged, bought, sold, and then merged again with its local rival, The Honolulu Star-Bulletin, to become in 2010 The Honolulu Star Advertiser. But the Advertiser archive is still preserved on microfilm in the Honolulu State Library. Who could have guessed, when those reels were made, that the record of a tiny birth announcement would one day become a matter of national consequence? But there, on page B-6 of the August 13, 1961, edition of The Sunday Advertiser, set next to classified listings for carpenters and floor waxers, are two lines of agate type announcing that on August 4, a son had been born to Mr. and Mrs. Barack H. Obama of 6085 Kalanianaole Highway.

In the absence of this impossible-to-fudge bit of plastic film, it would have been far easier for the so called birther movement to persuade more Americans that President Barack Obama wasn’t born in the United States. But that little roll of microfilm was and is still there, ready to be threaded on a reel and examined in the basement of the Honolulu State Library: An unfalsifiable record of “Births, Marriages, Deaths,” which immeasurably fortified the Hawaii government’s assertions regarding Obama’s original birth certificate. “We don’t destroy vital records,” Hawaii Health Department spokeswoman Janice Okubo says. “That’s our whole job, to maintain and retain vital records.”

Absent that microfilmed archive, maybe Donald Trump could have kept insinuating that Barack Obama had in fact been born in Kenya, and granting sufficient political corruption, that lie might at some later date have become official history. Because history is a fight we’re having every day. We’re battling to make the truth first by living it, and then by recording and sharing it, and finally, crucially, by preserving it. Without an archive, there is no history.

For years, our most important records have been committed to specialized materials and technologies. For archivists, 1870 is the year everything begins to turn to dust. That was the year American newspaper mills began phasing out rag-based paper with wood pulp, ensuring that newspapers printed after would be known to future generations as delicate things, brittle at the edges, yellowing with the slightest exposure to air. In the late 1920s, the Kodak company suggested microfilm was the solution, neatly compacting an entire newspaper onto a few inches of thin, flexible film. In the second half of the century entire libraries were transferred to microform, spun on microfilm reels, or served on tiny microfiche platters, while the crumbling originals were thrown away or pulped. To save newspapers, we first had to destroy them.

Then came digital media, which is even more compact than microfilm, giving way, initially at least, to fantasies of whole libraries preserved on the head of a pin. In the event, the new digital records degraded even more quickly than did newsprint. Information’s most consistent quality is its evanescence. Information is fugitive in its very nature.

“People are good at guessing what will be important in the future, but we are terrible at guessing what won’t be,” says Clay Shirky, media scholar and author, who in the early 2000s worked at the Library of Congress on the National Digital Information Infrastructure Preservation Project. After the obvious—presidential inaugurations or live footage of world historical events, say—we have to choose what to save. But we can’t save everything, and we can’t know that what we’re saving will last long. “Much of the modern dance of the 1970s and 1980s is lost precisely because choreographers assumed the VHS tapes they made would preserve it,” he says. He points to Rothenberg’s Law: “Digital data lasts forever, or five years, whichever comes first,” which was coined by the RAND Corporation computer scientist Jeff Rothenberg in a 1995 Scientific American article. “Our digital documents are far more fragile than paper,” he argued. “In fact, the record of the entire present period of history is in jeopardy.”

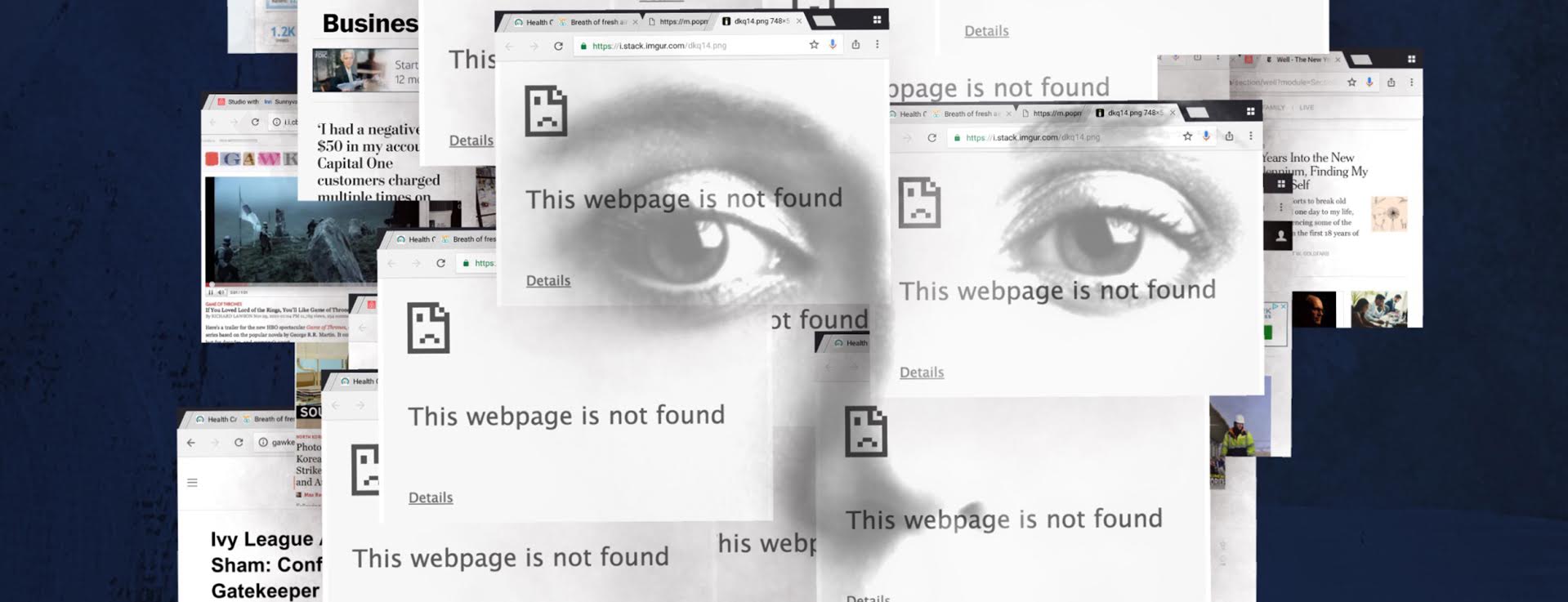

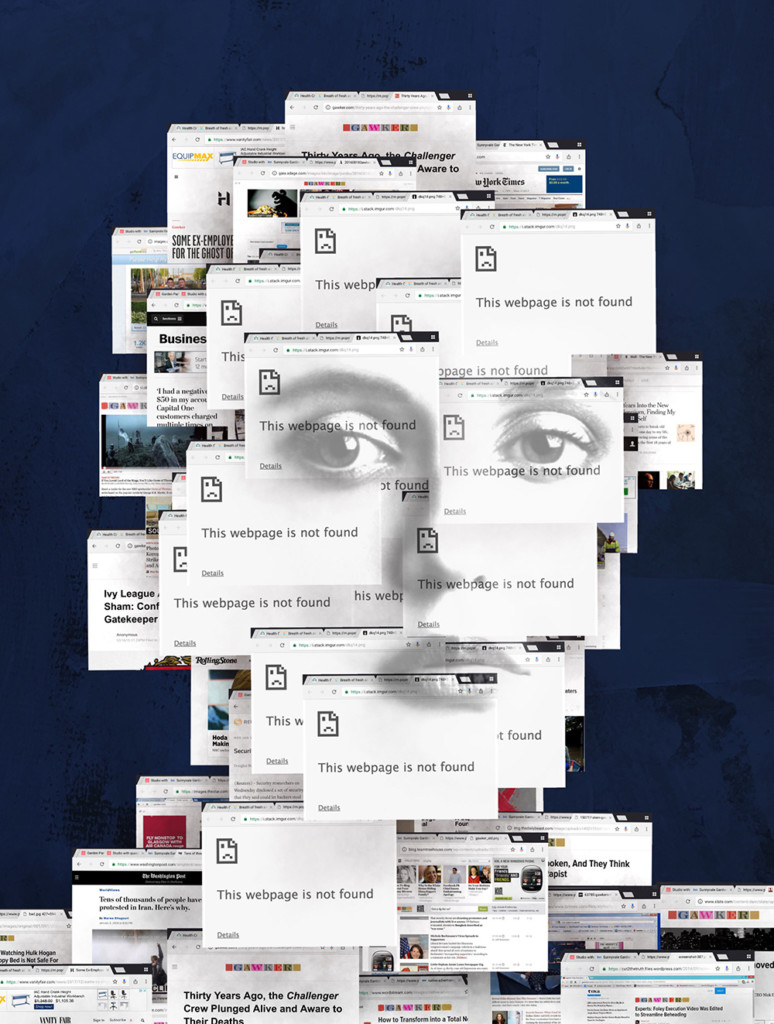

Illustration by Shannon Freshwater

On the other hand, says archivist Dan Cohen, “One of the good developments of our digital age is that it is possible to save more, and to provide access to more.” Fifteen years ago, he began work on Digital History, a book co-authored with Roy Rosenzweig. “There was already a good sense of how fragile born-digital materials are,” he explains, stressing that most archivists’ concerns aren’t new. “Historians have always had to sift through fakes and half-truths. What’s gotten worse is the sheer ease of creating fake documents and especially of disseminating them far and wide. People haven’t gotten any less gullible.”

In the 21st century, more and more information is “born digital” and will stay that way, prone to decay or disappearance as servers, software, Web technologies, and computer languages break down. The task of internet archivists has developed a significance far beyond what anyone could have imagined in 2001, when the Internet Archive first cranked up the Wayback Machine and began collecting Web pages; the site now holds more than 30 petabytes of data dating back to 1996. (One gigabyte would hold the equivalent of 30 feet of books on a shelf; a petabyte is a million of those.) Not infrequently, the Wayback Machine and other large digital archives, such as those in the care of the great national and academic libraries, find themselves holding the only extant copy of a given work on the public internet. This responsibility is increasingly fraught with political, cultural, and even legal complications.

We battle every day to make the truth, first by living it, then by recording and sharing it, and finally, crucially, by preserving it.

Press-hating autocrats, increasingly emboldened by Donald Trump’s notorious contempt for journalists, have grown brazen in recent years. North Korean state media erased some 35,000 articles mentioning Jang Song-thaek, the uncle of Kim Jong-Un, after his execution for treason in late 2013. Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan cracked down on his country’s press after a failed coup attempt in July 2016, shuttering more than 150 press outlets. The Egyptian government ordered ISPs to block access to 21 news websites in May 2017. This is to say nothing of broader crackdowns on public information such as Turkey’s ban on teaching evolution in high schools, or China’s recent attempt to force Cambridge University Press to censor journal articles.

Now let’s assume there are copies of these banned publications in public digital archives, such as the Wayback Machine. If a government wishes to remove information from the internet, but archivists believe the material in question to be of significant public interest and import, how are libraries and archives to respond? How do libraries balance the public interest against those with legitimate grounds for restricting access, such as rights holders and privacy advocates?

ICYMI: 11 images that show how the Trump administration is failing at photography

The Wayback Machine generally adheres to the standards of the Oakland Archive Policy, a template for the use of librarians and archivists in evaluating takedown requests developed at UC Berkeley and first published in 2002. When governments make such requests, the Oakland policy quotes the American Library Association’s Library Bill of Rights, adopted in 1939: “Libraries should challenge censorship in the fulfillment of their responsibility to provide information and enlightenment.”

The Library Bill of Rights also states that “books and other library resources should be provided for the interest, information, and enlightenment of all people of the community the library serves. Materials should not be excluded because of the origin, background, or views of those contributing to their creation.” When we consider that the internet is a library, and that the community it serves is all mankind, the responsibility of digital archivists acquires a gravity that is hard to overstate.

Until June 2016, when it filed for bankruptcy, Gawker provided intelligent and unrestrained commentary on events of the day to a mass audience of tens of millions. The company fell victim to a barrage of lawsuits, filed by different plaintiffs but paid for by one person, the billionaire PayPal co-founder and Trump supporter Peter Thiel, whose business, political, and personal dealings were frequently mocked by Gawker, which he once characterized as “the Silicon Valley equivalent of Al Qaeda . . . . I think they should be described as terrorists, not as writers or reporters.” Most people who don’t care for a magazine are content to refrain from reading it. But Thiel went much, much further.

Thiel’s coup de grâce against Gawker originated in a bizarre Florida lawsuit involving a blurry security-camera sex tape featuring the washed-up wrestler Hulk Hogan and Heather Clem, the wife of Hogan’s friend, radio personality Bubba the Love Sponge. Despite having discussed, in front of the vast radio audience of Howard Stern, intimate matters far too crude to recount here, Hogan was awarded a $140 million judgement for the invasion of his privacy and infliction of emotional distress by a six-person jury in Pinellas County. (Hogan and Gawker eventually reached a $31 million settlement.) Gawker Media Group was forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Its websites were sold to Univision for $135 million—with the exception of its flagship site, Gawker.com, which the publicly traded corporation did not want to bear the risk of owning.

Peter Thiel spent millions funding litigation in order to destroy Gawker and may be looking to finish the job by eradicating its archive.

The disposition of the remaining assets of Gawker Media Group, including the flagship site and its archive of over 200,000 articles, is still before a New York bankruptcy court. In January, Thiel submitted a bid for these assets, after earlier complaining to the bankruptcy judge overseeing the auction that the Gawker estate’s administrators were barring him from doing so. Thiel spent millions on the Hogan case alone with the express purpose of destroying Gawker, and may be looking to purchase these assets in order to protect himself from a public airing of his secret campaign of litigation; he may also intend to finish the job of ruining Gawker by eradicating their archive. Suspicion of the latter motive has been voiced repeatedly both in court and in the press.

What would be missing if the Gawker archive were to disappear, aside from years’ worth of mockery of Peter Thiel? Essays on the Black Lives Matter movement, on personal grief and Donald Trump’s hair, on Silk Road and Reddit’s Violentacrez. A. J. Daulerio’s 2003 interview with the late Fred Phelps. A series of pieces exposing Amazon’s cruel treatment of its workers. Letters from death row inmates. Tom Scocca’s final post on the dangers facing the free press, “Gawker Was Murdered by Gaslight.”

Unlike politicians or entertainers, journalists have a professional obligation to tell the truth—not only for ethical reasons, but also because they can easily be sued, fired, or publicly disgraced if they publish things that aren’t true. Some examples of potentially dangerous material would be the explosive accusations against Harvey Weinstein reported by Ronan Farrow in The New Yorker and by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey in The New York Times, or the Times’s coverage of the sexual misdeeds of Louis C.K., or the mea culpa of Ta-Nehisi Coates, writing in The Atlantic, “I believed that Bill Cosby was a rapist.”

All three of these stories had earlier roots at Gawker. A blind item in 2012 described the experiences of two female comedians who were sexually harassed by Louis C.K. In 2014, Gawker reignited public interest in the allegations against Bill Cosby after years of media silence (“Who Wants to Remember Bill Cosby’s Multiple Sex-Assault Allegations?”). A 2015 piece on the “despicable open secret” of Harvey Weinstein’s sexual misconduct asked readers for their help in exposing the truth. Gawker took the first crack at many risky stories, thereby clearing the path for “respectability.” In the absence of journalists willing to take such risks, it’s not at all clear whether such stories would ever have come to light in the mainstream press.

But the no-holds-barred approach could prove dangerous, as it did in the summer of 2015, when Gawker published private details of the gay sex life of a married Condé Nast executive. The decision to run this story met with criticism inside the profession and out. Gawker management removed the post, and Editor in Chief Max Read and Executive Editor Tommy Craggs resigned in protest.

“A company of bomb throwers can’t start hiding the evidence when a bomb goes astray,” Craggs tells me. “There should be a record of your fuck-ups and your triumphs, too.” In a similar spirit, he favors the preservation of Gawker’s archive as “a record of how life was lived and covered on the internet for an era. Taking that away is leaving a huge hole in our understanding.”

Peter Thiel is not the only trigger-happy rich man with a media axe to grind. Joe Ricketts, the Trump-supporting billionaire owner of DNAinfo and Gothamist, peremptorily shut both publications down in November 2017 after his employees voted to unionize. Ricketts had made his feelings about unions manifestly clear in a blog post he published during the negotiations: “Why I’m Against Unions At Businesses I Create.”

The archives of both publications disappeared in one fell swoop on the day the closure was announced, leading the just–laid off journalists to share tips on Twitter about how best to extract their clips, which would be useful at the very least in securing future employment, from Google’s search engine cache. The sites were later restored—for how long, who can say?—but the point had been made yet again. All it takes is one sufficiently angry rich person to destroy the work of hundreds, and prohibit access to information for millions.

Historically, the Wayback Machine has sought to skirt legal complications, and provides explicit instructions for rights-holders and publishers who don’t want their material crawled or archived, as well as tools for those who wish to facilitate preservation. I emailed the Wayback Machine’s founder Brewster Kahle with a description of the Gawker case, and asked what he thought might happen if a single person were to buy a large archive of historical interest with the sole aim of annihilating it. “It’s very disturbing,” he replied, and referred me to Mark Graham, who heads up the Wayback Machine. “We’re looking into these things very closely,” Graham tells me.

In January, the Freedom of the Press Foundation, a non-profit organization affiliated with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, announced an initiative in partnership with the Internet Archive to produce and maintain archives of material threatened by the “billionaire problem,” including Gawker and the LA Weekly, which saw most of its editorial staff laid off last November after it was purchased by a group of investors who placed the Libertarian-leaning opinion editor of the Orange County Register in charge of the operation. “Obviously, we’re hoping that the Internet Archive is able to host this material indefinitely, and as an organization, they’ve got a very strong track record of standing up for speech,” says the FPF’s director of special projects, Parker Higgins. But he adds that they are already drawing up contingency plans should the new owners of the publications confront the project with takedown notices. “We are working on ensuring that the Archive’s continued hosting isn’t a single point of failure here, though we’re not quite ready to go into details on that,” he says.

ICYMI: “One of the most elaborate undercover stings in American journalism history”

In addition to these efforts, there’s evidence that next-generation archival strategies are already under development at the Internet Archive and elsewhere. Kahle hosted Vint Cerf and other internet pioneers at the June 2016 Decentralized Web Summit in San Francisco, a gathering dedicated to exploring the design of a far more widely distributed, decentralized internet. Decentralized networks are less vulnerable to censorship or tampering, as for example in the peer-to-peer InterPlanetary File System, which protects files by storing many copies across many computers. In combination with the blockchain technology that underpins the Bitcoin cryptocurrency, systems can be designed to produce incorruptible archives, provided the networks they’re running on are sufficiently robust.

An oft-cited feature of the new internet under discussion at the Decentralized Web Summit was this type of tamper-proof and permanent “baked-in” archive. Cerf, who despite his white beard and dignified presence is also playful and waggish (“Power corrupts, and PowerPoint corrupts absolutely”), spoke of the need for new kinds of “reference space” held in common by cooperating entities, the way URLs are held in common now. Kahle bounced around in characteristic style as he outlined his vision of a global peer-to-peer network with built-in archiving, all using techniques already developed. “Can we lock the Web open?” Kahle asked. “Can you actually make it so that openness is irrevocable, so that you bake these values into the Web itself?—and I would say, Yes. That is our opportunity.”

Our records are the raw material of history; the shelter of our memories for the future. We must develop ironclad security for our digital archives, and put them entirely out of the reach of hostile hands. The good news is that this is still possible.

Digital vs. print

By Karen K. Ho

310,000,000,000

Web pages captured over time by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. But the figure is misleading: Information published to the Web changes so frequently—a Harvard Law School study found that 70 percent of URLs cited in law reviews are no longer functional—that any snapshot of the internet is incomplete at best. “Things stick around for much shorter and [are] changing constantly before they disappear,” the Internet Archive’s Jason Scott told The Atlantic.

60,000,000

Newspaper pages scanned, but not searchable, in the Google News Archive. Starting in 2008, Google created one of the largest keyword-searchable archives of newspapers, going back for more than a century—all free to use on the Web. But in 2011, with little explanation, the archive was made unsearchable. While some pages can be browsed, newspapers such as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel have pulled their content due to agreements with other digital archive providers.

1

Remaining employee in The New York Times’s morgue. At its height, the paper’s archive once employed dozens of people who dutifully clipped, organized, and filed every story that appeared in each day’s edition. In 1974, when there were 28 employees, a Times editor once said, “The morgue is the lifeblood of this paper. We couldn’t put out a paper without the morgue.” Today, the lone employee is Jeff Roth, 58, who oversees a collection of tens of millions of clippings and millions of photographic prints.

0

Number of archived complete press runs of The Washington Post.

The Post has thrown out many of its printed copies, relying instead on photographic and digital archives. Collections of the Post at major libraries, such as the American Newspaper Repository Collection at Duke University, are spotty. Such is the case for most papers: The New York Times threw out its paper archive in 2006, while a spokesman for The Wall Street Journal notes, “We lost the majority of our print archive during the 9/11 attack. At the time our offices were at 200 Liberty Street, directly across from the South Tower” of the World Trade Center.

Maria Bustillos is the founding editor of Popula, an alternative news and culture magazine. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, The New Yorker, Harper’s, and The Guardian.