In the early 1820s, when the only international news came in with the ships, several New York newspapers banded together to keep a small newsboat ready to meet incoming schooners. But in 1827, one of the papers on board, the Journal of Commerce, withdrew from the agreement: the editors didn’t want the boaters to work on the Sabbath. The Journal bought its own schooner. “One of its rivals then bought an even faster boat, and things escalated from there,” Andie Tucher, a historian and journalist who directs the Communications Ph.D. program at Columbia Journalism School, says. The first scoop war was born.

By the summer of 1863, competition was fierce. A New York Tribune reporter was about 10 miles from Gettysburg, trying to cover a cavalry raid, when the battle opened. The town’s telegraph operator told him the wires had been cut. “The Trib’s man gathered up a work crew, rented a handcar from the president of the railroad, and took off to find the break and repair it,” Tucher says. “In return, he demanded that the telegraph operator not let anyone else but him use the wire, and sent off a scoop.”

After that, editors got creative. A January 1939 issue of The Rotarian documents the New York Evening Journal’s “aviary of 75 feathered reporters,” carrier pigeons trained to deliver exclusive stories or photographic negatives in lightweight aluminum tubes. “The Hearst papers in New York did this in the 1930s, when (for example) they needed film from Ebbets Field to get back to the office in Manhattan by an early evening deadline,” Chris Bonanos, city editor of New York magazine explains in an email.

Recently, when the Justice Department delivered Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report to Congress on CD-ROM, journalists began comparing notes about how they submit and revise their work for editors. In the age of Google Docs, it can be hard to imagine what came before. We decided to take a historical look, by asking journalists whose careers spanned the past several decades about how they have filed. Their memories have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Fifties

Max Frankel, reporter and later executive editor at The New York Times, 1986-1994

In 1956, I was covering the Hungarian revolution for the Times. We filed mostly by telegraph, but some of it we were beginning to do by telephone. Like, from Vienna, we could telephone either London or New York and just speak normally because they would record and transcribe it.

If we were using telegraph, we would be charged usually by the word. So we got in the habit of contracting. “UniStates,” instead of the United States. We called it “cable-ese.” We would repeat negatives to make sure that they wouldn’t get lost. We would write NOT rp NOT. It’s very dangerous if you drop a “not”—the whole point of the story could be distorted.

My next assignment was in Moscow. If the censor cleared your story, it would go out in cable-ese by cable. If we wrote for telephone, I would often use what I’d learned about the repetition of “not” to get a sensitive idea past the censor. I might make a sentence in the negative but then when dictating over the phone to London I would drop the “not” and convey the opposite idea. The censor would be listening, but if I talked fast enough I could get by them that way.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (center) being interviewed by actor and activist Harry Belafonte (right), and George Goodman, community news director at WLIB radio, New York, 1957. Photo: Austin Hansen/ The New York Public Library

Ed Kosner, Newsweek editor, 1975-1979, New York magazine editor, 1980-1993, Esquire editor, 1993-1997, New York Daily News editor, 2000-2004

I called Martin Luther King Jr. one night at two o’clock in morning, and asked him about some development. There was a pause, and he answered, “I would say, comma,” and dictated a perfect paragraph, with punctuation and quotations.

Max Frankel

There was another way to file, especially sensitive feature material or film rolls, and that was to give it to a tourist who was going back to America. You could be a little freer making snarky comments that way. When you’re alone behind the iron curtain in Moscow, you welcome an American face. There was a sense of, we were all in this together. You could trust an Italian traveler, or British, or French.

There was also a couple in Czechoslovakia who had a cable forwarding service. You could call them up, give them copy, and they would put it on cable for you from other places.

Sixties

Dan Okrent, LIFE magazine editor 1992-1996, editor of new media, Time Inc., 1996-1998, corporate editor, Time Inc., 1998-2001, public editor The New York Times, 2003-2005

Before computerized typesetting, everything would be typed on a typewriter, and then someone in the composing room, sitting in front of a linotype machine, would retype the whole thing.

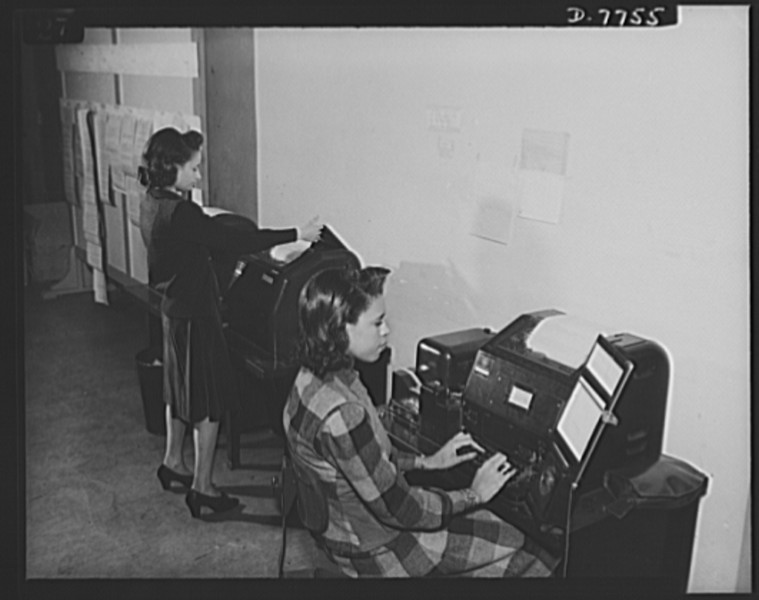

The teletype room of the Bureau of Publications and Graphics, 1944. Photo: Roger Smith/ Library of Congress

Max Frankel

Kennedy was in office when I first worked in the New York Times bureau in Washington. We had a full-time teletype operator who filed all our copy to New York. You’re sitting at a machine, like a big souped-up typewriter, and it would print out instantaneously at the other end. Teletype was the way to file whenever you were in a steady location. We would set up our political convention coverage and have teletype operators right there. When we were traveling with the president it would be mostly telephone to the recording room at the Times.

Robert Hodierne, reporter and photojournalist in Vietnam. Freelance, 1966-1967; Pacific Stars and Stripes, 1969-1970; Army Times Publishing Company senior managing editor, 2001-2008

If you were out in the field some place and wanted to call in your story, you couldn’t just direct dial the office in Saigon. Maybe you were with the marines in Hue; there was no direct line from the north. You had to get patched through a series of military switchboards to the civilian phones. The connections were frequently awful. You had a hard time understanding one another, and right in the middle of dictating a story you’d lose the connection and have to start all over again.

Once you were back in Saigon, if you were with one of the wire services, you were connected by telex to your office in New York. It went through the South Vietnamese government-owned phone system. If things were going on that they didn’t want the world to know about, they’d turn the overseas telex lines off, and we wouldn’t be able to file.

Photography was even more of a pain in the neck. If you were out taking pictures, and you had to get the film to Saigon, you were hitching rides on military planes to get back where the film could be developed and prints made, and then the prints would be sent by radio telephone back to New York.

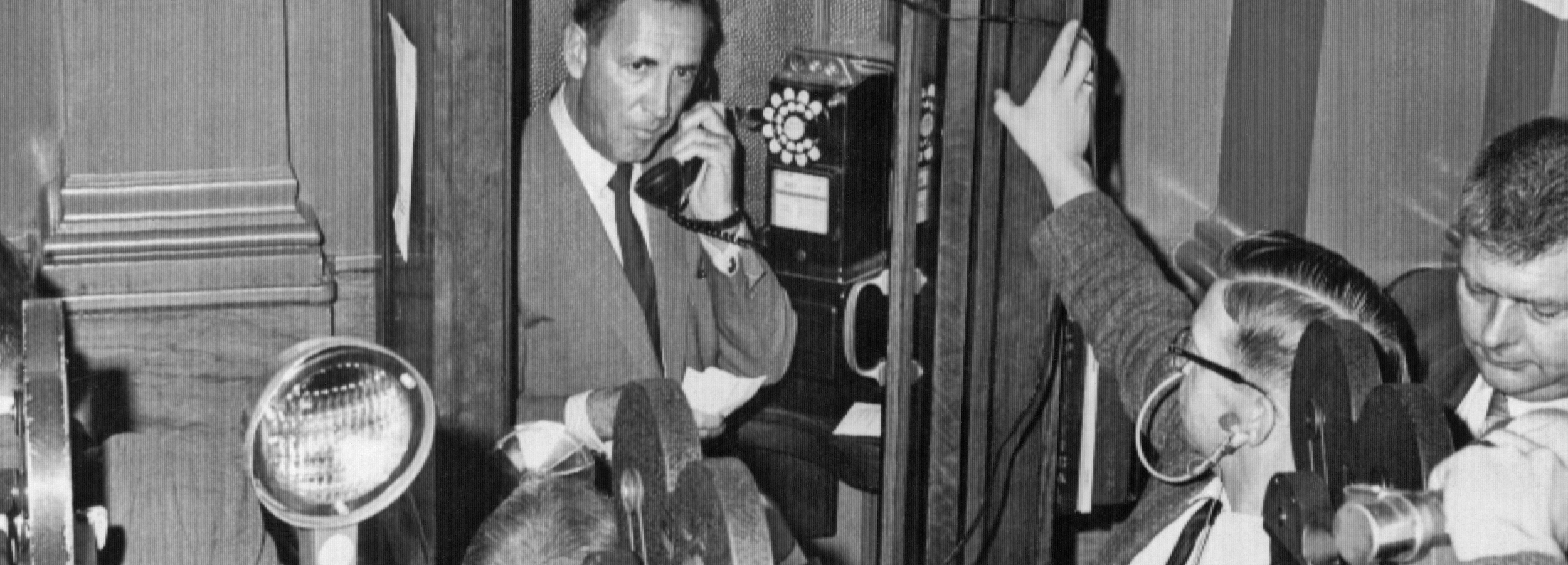

Reporters and camermen wait outside a phone booth while promoter Harold Conrad seeks a new site for the Cassius Clay-Sonny Liston heavyweight title fight. Boston, 1965. Photo: Underwood Archives/Getty Images

Max Frankel

Wherever there was a large number of correspondents and a shortage of telephones, there was a fierce competition for getting into a phone booth. There was a particular fight, as I recall, when Kennedy was assassinated. The UPI and AP correspondents were in the same car, and they were physically fighting for the car’s phone setup.

Jim Seymore, People executive editor, 1987-1990; Entertainment Weekly managing editor, 1990-2002

Foreign correspondents for TIME, Inc. filed on teletype machine. Back in the day, part of the job was to smooth the way for New York honchos when they came to town. Particularly for Henry Luce, who insisted on carte blanche and interviewing anyone he wanted.

Seventies

Dan Okrent

I was a copy boy at the Detroit Free Press the summers of my sophomore and junior years in college. The editor would shout, “Copy!” We would take these grainy, cheap copy sheets, roll them up, put them in pneumatic tubes that went to the composing room. I can still hear the whooshing noise.

Linotype operators in the composing room of The New York Times, 1942. Photo: Marjory Collins/ Library of Congress

Jim Calio, LIFE magazine Los Angeles bureau chief, 1990-1995

I started after J-school at a small paper in Massachusetts, the Lowell Sun. I had the city hall beat from 1973 to 1974. At 9am I’d walk up to speak with the City Manager or the Mayor. I had a 1pm deadline, so I’d start writing at noon or later to keep it fresh. You would use scissors and paste to move the paragraphs around. You’d hand to the editor at his big u-shaped desk, and then it went to old linotype machines. Our office was so old, the Underwood typewriters had flat keys with the letters worn off.

Filip Bondy, sports writer for New York Daily News, 1983-1990; sports writer for The New York Times, 1991-1993

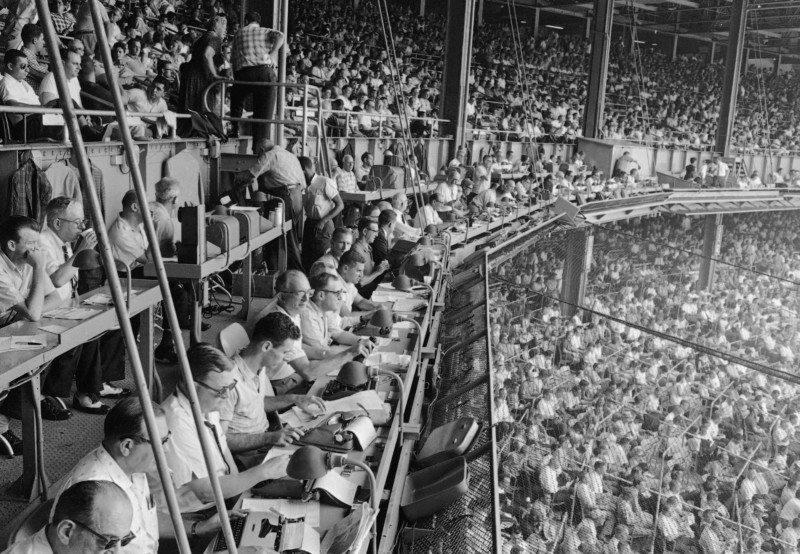

In the 1970s, I started with dictation at games. We would write on typewriters, little Olivettis, and read the stories over the phone. Some of the typists we were reading to were very good, and some were torturously bad. That was a big advantage The New York Times and the New York Post had, was a tape recorder. You just read the story in. We just had the hunt-and-peck typist.

The press box at Yankee Stadium, 1961. Photo: John Rooney/ AP

Ed Kosner

The Watergate thing was interesting because it was so totally different from today. The problem was the transcripts were in Washington, and we were in New York. So a Newsweek assistant in the Washington bureau would go to National Airport, like 10 o’clock, and find a stewardess from Eastern Airlines or National Airlines, and hand over the transcripts and maybe 20 bucks or something. And the stewardess, or as the term was used, “pigeon,” as in carrier pigeon, would literally fly the stuff to New York. The assistant from New York would be waiting at the airport and deliver the transcripts to me.

From left: Osborn Elliot, editor of Newsweek; presidential hopeful Richard Nixon; Bob Christopher, foreign editor of Newsweek; and Ed Kosner at Newsweek‘s offices, 1966 or 67, photo courtesy of Ed Kosner.

Jim Calio

You had to essentially work between the film and the copy. We used a Moviola machine. When you got back from the field, you spliced the film, matched it to the sound. The trick is not to say “here is this” in the narration—let the film speak for itself. You want to bounce the narration off of the film. Great news reporters still do that.

Lynne Sladky, Associated Press staff photographer, 1990-present

My first big job was at UPI in Miami. They sent me to Haiti to cover the overthrow of Duvalier. When you left Miami, you had to take an enlarger, chemicals, paper. You would set up a darkroom in your hotel bathroom. I can’t believe the airlines let us on with all the toxic liquid chemicals.

Pat Anderson films UN troops after the earthquake in Haiti. Photo courtesy of Pat Anderson.

Eighties

Pat Anderson, director of photography and cameraman for National Geographic, Smithsonian, BBC, CNN, Vice, US Defense Department, Swiss Broadcasting, and Al Jazeera, 1979-present

In 1980 we went to the Republican convention in Detroit. The only way we could do standups with live remote stuff was by using a microwave truck to broadcast the signal. But we had no way of telling the correspondent when he was live. So we had a kid we called the “human repeater,” who literally stood on the roof of a building, and his radio could reach the master control truck [receiving a signal when the feed went live]. The kid would say, “OK tell him he’s live.” There was a lag of about two or three seconds.

During the Falkland Islands War, I went down as one of the cameramen for the BBC. I spent six weeks or so in Buenos Aires. We could not feed out because the Argentinians would censor the pieces that we made. So we had a courier who would fly the tape every morning to the TV station in Montevideo, in Uruguay, across the river. BBC London was four hours ahead of us. So to make their evening news with the latest updates, we had to finish editing by about 11am.

The night that President Galtieri got on TV and basically surrendered, people in Argentina were stunned because all the newspapers were saying just the opposite. They even had fake photographs in the newspaper of British carriers sinking. That night it was chaos in the streets. The police were shooting rubber bullets at us. We were hiding in the alleys and just grabbing shots when we could. Tear gas everywhere, it was quite a scene. But we still had to take tapes to Montevideo.

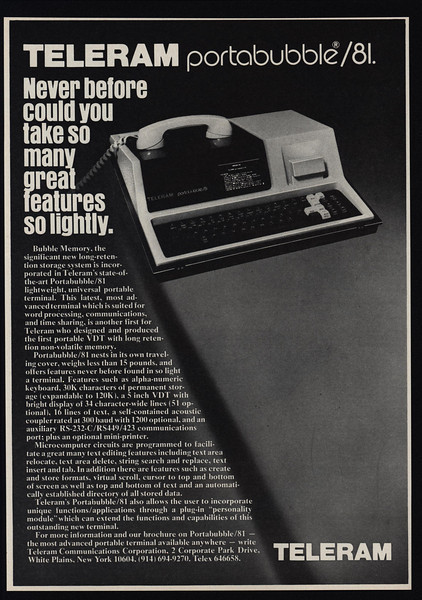

I said take my Portabubble. But they wanted no part of it.

Filip Bondy

We got the first generation fax machines, and they were really weird looking. They had rollers, like a typewriter roll. You could send your story to the office that way. They didn’t belong to us, there were separate subcontractors who showed up at the games. There’d only be one or two for the whole stadium. The New York Times always got to go first, I was at the little Paterson News.

Then came this amazing machine called a Teleram. Somehow it taped your story and sent it. It was gigantic, rectangular, very heavy to carry. Maybe one out of every three stories would get lost.

Then we went on to something much better, the PSI machine. There was a little TV inside a plastic case. You stuck the phone receiver into it. It had a very limited storage capacity. It could only hold one or two stories maximum before you had to erase. If you typed too much it would just start replacing what you had previously written.

LynNell Hancock, Village Voice and New York Daily News, education reporter, 1985-1994; Newsweek education editor, 1994-1998; contributor to Newsweek, Columbia Journalism Review, The Nation, and The New York Times

The first computers, you needed software just to type. The first one was Bank Street Writer, and the second was Xywrite, and they were complicated to learn. You had to boot them up with one floppy disk on one side and then stick your other floppy disk on the other side, and you had both of these going at once. The story was supposed to be saved on the second floppy disk, right? I can’t tell you how many times I lost everything on the second floppy disk because there’s no hard drive.

I would carry this disk on the 4 train from the Bronx down to the Village Voice at Union Square, always terrified that I was going to get mugged or something, because I had no other copy of it. I didn’t have a printer at home, and I couldn’t carry my machine down there, so I just had this disk. One of the 3”-by-5” ones, literally floppy. Then you’d have to find an IT person in the Village Voice who would reformat it for whatever their program was. It would take hours and you could lose it in the middle. And these were the five-thousand-word cover stories.

You had to calculate making your deadline with all of this, just delivering the story, and then worry about losing it because you’d have to retype it into the machine.

Ad for the Portabubble, 1981.

Filip Bondy

Then there was this thing called a Portabubble. It was a giant machine, very heavy, maybe a foot-and-a-half cube. You would stick the actual phone receiver into it. The problem with this one was it had a very delicate noise level. I remember there was an organist at Chicago Stadium, where the Bulls and the Blackhawks played. She would continue to play organ long after the game was over. We’d be trying to write stories on the Portabubbles. She’d play a note, and they’d all print out random letters, and we’d scream down to her to stop.

I remember getting mugged after a game at Shea Stadium. One guy had me by the neck from behind. I said take my Portabubble. But they wanted no part of it.

Ken Jarecke, Contact Press Images photojournalist, 1985-present

If you were traveling with the White House or a campaign, all the magazine photographers used the same courier. Someone would call and they would come to the hotel at 11 or midnight. One of us would wait up and hand everyone’s film to the courier.

Yunghi Kim, Contact Press Images photojournalist, 1984-present

I remember going to cover a Red Sox game in Baltimore. One of their stringers was assigned to handle my film for deadline. You would shoot 15 minutes of the first inning, then hand off your film, and they had a darkroom in the stadium.

You would start printing when the negative was still wet. You had to be really skilled in processing and printing as well as shooting. Literally 15 minutes. The newsroom would have a space left open for that one photo.

By the late eighties, early nineties, the AP was using the Leafax. That was revolutionary. It cost $30,000; you had to carry it. It was the size of suitcase and heavy like a lead weight. Papers would buy it just to transmit photos. There were three color drums, like the old fax machines but for Page 1 color photos.

You’re editing in your mind as you shoot, making choices ahead of time.

Dan Okrent

By the time the eighties were well under way, we were using the Atex. It was the first commonly used electronic system in magazines. There was a black screen and green type. You were composing a piece that would be translated to hot metal or to offset, skipping the composing room. That’s when the composing room begins to disappear. Only a few people were left making the adjustments. That was an enormous change in the staffing.

Ken Jarecke

For Tiananmen Square, we had a Time bureau in Beijing, so all I had to do was drop the film. Everyone’s agency would make a deal. You might have a group of 20 photographers with a loose relationship with Time, or Paris Match, or Newsweek, or Figaro to get their film in. Overnight Monday, the Asian version of Time or Newsweek would arrive in Beijing. Everyone would eat breakfast, and it would be the first time we saw our film.

Nineties

LynNell Hancock

There were the Crown Heights riots when I was at the Daily News in 1991. I remember my colleagues saying the pay phones were usually the territory of the drug dealers. But during these riots they were the only way the crime reporters could file their stories remotely to their offices before the competition. Some people would identify a phone in another neighborhood before they went to the scene, so they could rush there in a cab and call in their story later. It added to the adrenaline and the fun.

Jim Calio

Photographers would bring their film in to my office in LA. We would courier it to New York. But with a big show biz story, like one we did on Roseanne Barr’s wedding, we had the exclusive. We couldn’t use a courier—someone could intercept that. I was there, the paparazzi were in the trees outside her home. Mark Senate shot a lot of polaroids to test. We gathered those up so no one could sell them to the tabloids. Then Mark’s assistant flew with the film back to New York. Same thing with the ‘94 earthquake, we had to physically send the film back by plane.

Silvana Paternostro, freelance Latin American journalist for publications including The New York Times, Time, and Newsweek, 1989-present

I was a stringer for the Times in Managua during the 1990 elections. We got no bylines, it was so unfair. I would do the reporting, all the interviewing. Then I would go write it up, give them my notes, pointing out the good quotes. My bureau chief would take all the reported material, slap it into a story, put his name on it, and send it to New York. That was the standard. Then I did a lot of reporting for Newsweek and Time. It was the same thing. You’d send your “color” to New York, that’s what they called it, and the piece would be written there. You’d get something little at the end, “With reporting by Silvana in Ecuador.”

You had to calculate making your deadline with all of this, just delivering the story, and then worry about losing it because you’d have to retype it into the machine.

Jim Seymore

A story would go to senior editor who would either edit or rewrite it completely. I had many a late night rewriting. Next the story went up the line to the assistant managing editor. At each point, let’s say I was senior editor, I had to put my initials on it. If I didn’t approve I would write “Not JWS.” The copy department would fix it and send back, I’d edit again. Next it would go to the managing editor, who did same process all over again. That was Time Inc.’s version of group journalism.

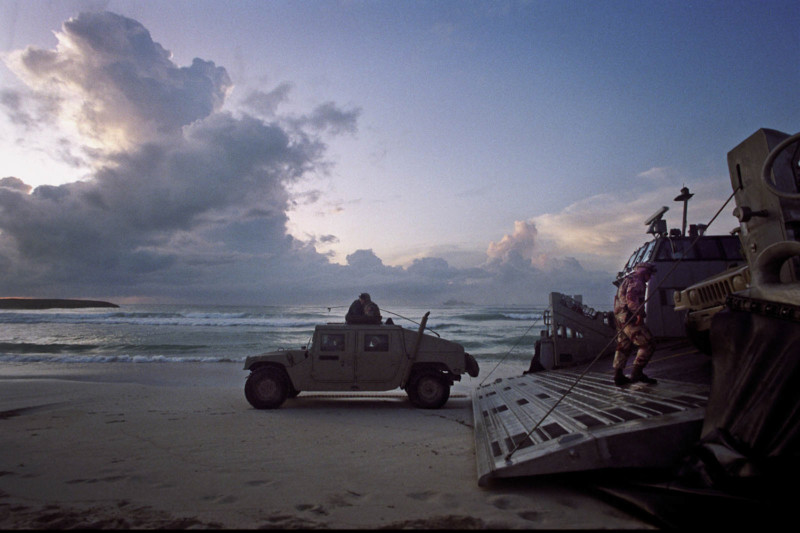

On the beach waiting for US Marines in Somalia, 1992. Photo by Yunghi Kim

Yunghi Kim

In a conflict like Somalia 1992, the AP would have a huge operation. They would set up a darkroom in a hotel room bathroom to process their own film and any film for members who needed it. Some photographers travelled with their own film developing kits. You’d have an extra suitcase with all the developers, wheels, and tanks to process the film. I would ship film back by courier.

You couldn’t shoot a lot on deadline because you would miss the deadline, processing all that film. You really had to know what you were shooting and what the paper’s needs were. You’re editing in your mind as you shoot, making choices ahead of time.

Ken Jarecke

When we went digital, you would be on a plane working, in the hotel working, on a bus working, captioning, toning files, transmitting big packages of image files. Not only the photographers, but the writers. Everyone was online at the hotel. Some video guys were uploading B-roll. It would be a crazy amount of data on one portal at one hotel. You’d be up all night sometimes. People fell asleep on their laptops all the time.

Ken Jarecke on assignment for Time in Montana, 1996. Photo: Ken Jarecke/Contact

Yunghi Kim

Photographers would know which hotel rooms had good phone lines, everyone would share. Sometimes you’d stay up all night scanning the film with the new Nikon scanners. You would literally hook up your primitive computer to a phone line and hope that your picture goes through. It would take hours scanning and transmitting. Some journalists were really good at splicing phone lines into their computers.

When one hour photo labs came out, you could process color negatives in one hour, even in Indonesia. So you would shoot both color for deadline, and then either black and white or chrome for later. You’d ship that. In Kosovo in 1998, I went in to Pristina, and some local guy was able to open his one hour photo after the war. We all went to him.

Duy Linh Tu, video journalist, 1999-present

Apple released Final Cut Pro. It was rudimentary, and it was terrible, but you could edit your own videos. Not on a laptop, you definitely still needed a desktop, but you could pay $1,000 or $1,500 and do it. If you’re a freelancer, that meant you had more shoot days, which meant you had more control, which meant you could actually make the money in between gigs, because you got to hire yourself out.

Aughts to today

As technological advances sped up, “It was a perfect storm,” Duy Linh Tu says. “At the same time dot.com 1.0 came around came high speed bandwidth. At that time it was mostly still dial up at home, but at work you could see video. This opened up a lot of opportunity for non-traditional broadcasters to shoot shitty little videos, and to be able to put them online. It totally changed distribution.” Email and collaborative editing software changed written reporting, too. But some outlets remain attached to the old ways. “I just did a review of a book in the New York Review of Books just last year, and they are still using ancient methods, editing by hand.” Silvana Paternostro says. “I would get scans of hand-marked transcripts.”

ICYMI: The site where journalists are leaving anonymous comments about their newsrooms

Amanda Darrach is a contributor to CJR and a visiting scholar at the University of St Andrews School of International Relations. Follow her on Twitter @thedarrach.