In 1961, John B. Oakes was appointed to lead the editorial page of the New York Times. “Oakes” was a rewrite—his father, George, had tacked it onto the name Ochs, as in his brother Adolph S. Ochs, who bought the paper, in 1896; they were all part of the family business. John B. Oakes was deeply concerned with the problem of groupthink in America and wanted to use his platform as a way to challenge conformity. His department recruited non-journalists—subject-matter experts, public officials, novelists—to challenge prevailing beliefs, disagree with one another, and let readers draw their own conclusions. In 1970, he gave his pundits a new venue: the Times op-ed page. As Michael J. Socolow, a media historian, has described in Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, the page soon sparked controversy, which also meant notoriety. And it was “remarkably cost-effective,” he added: “the first six months of op-ed operation produced a net profit of $112,000 on $264,900 of revenues.” Within two years, the Chicago Tribune, Boston Globe, and other papers had established similar pages of their own. Op-ed contributors went on to become enormously influential in shaping the national political discourse.

Recently, fifty years later, it was reported that the Times was publishing a hundred and twenty opinion articles per week, providing a podium for authors to air their takes not only to the paper’s readers but to the whole of the internet. Among the astonishing number of pieces, there were some infuriating ones; in June, James Bennet, the editor of the opinion section, resigned after the Times published a particularly inflammatory op-ed by Tom Cotton, a Republican senator from Arkansas, under the headline “Send In the Troops.” The piece relied on a debunked conspiracy theory and called for the military to crush the summer’s protests against racist violence. “Times Opinion owes it to our readers to show them counter-arguments, particularly those made by people in a position to set policy,” Bennet offered, by way of defense; then he admitted that he hadn’t vetted the submission before it went online. Later, he apologized to his colleagues, saying that he’d let his section be “stampeded by the news cycle.” In a memo to staff, A.G. Sulzberger, the publisher of the Times, diagnosed a breakdown in the editing process, promising that the opinion desk would now enter “a period of considerable change” and produce less.

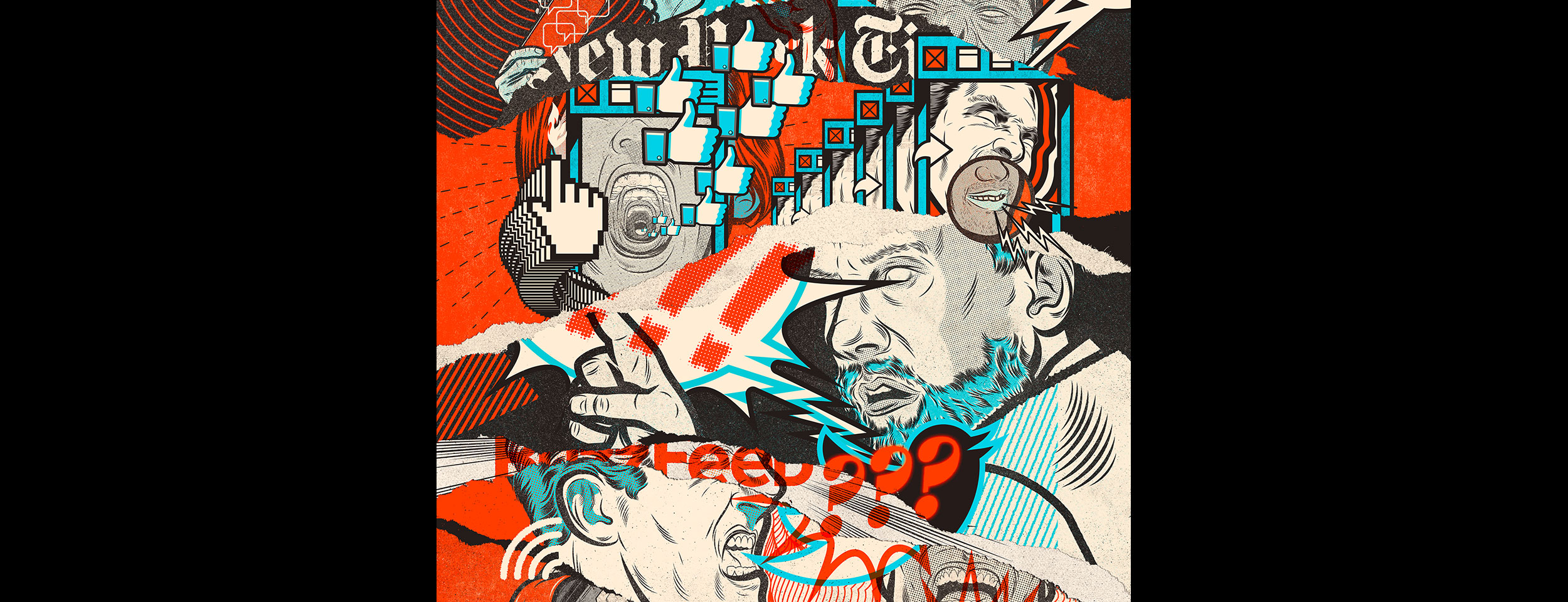

An unavoidable question reverberated across the media world: Why must we read so many bad opinions? The abundance of takes, as we know, is not limited to one outlet or type; everywhere, underpaid and overworked writers and editors are trying to squeeze as much copy as possible into a day: some great, some terrible, some concerning news that will change in a few hours. “Now,” Fred Hiatt, the Washington Post’s editorial page editor, told me, “if you want to have a rich opinion section that is both presenting really diverse viewpoints on the main stories of the day and surfacing interesting cultural and academic and political and social issues that are not on the front page, you can’t do that in five pieces a day. If you’re on top of that, trying to provide a useful forum for debate about what’s happening in the Middle East or in China, you need more quantity.” Sewell Chan, the editorial page editor of the Los Angeles Times, pointed to the “complete multimedia cycle,” in which cable news networks “are nonstop opinion machines.” He continued, “It has become harder, I think, for serious, civil, carefully argued, rigorously presented opinion to break through.” Merrill Brown, an erstwhile editor and the founder of a business-of-journalism startup called the News Project, described the pressure that opinion purveyors feel: “Everybody wants to get today’s take right,” he said. “But ‘thoughtful commentary’ on the day’s news is almost an oxymoron.” The result, he added, “is more about being clever than necessarily doing your homework.” Supplying one’s opinion, whether or not one has something worthwhile to say, may be an essentially American pursuit; hearing all those opinions can be exhausting and exasperating.

It may come as no surprise that the ubiquity of opinion pieces in recent years mostly comes down to money. As new platforms have chipped away at the traditional role of informational gatekeepers, legacy news organizations have become a bit more like everybody else, jostling to make themselves heard above the ceaseless cacophony of opinions, gossip, breaking stories, and misinformation blaring forth from social media, cable television, and talk radio. News is commoditized; outlets are desperate to stand out; opinionated analysis has become a crucial value proposition. Just as Oakes discovered as the architect of the New York Times op-ed page, commentary is a cheap and powerful attraction. His successors across the media industry, dejected after years of economic hardship and the acute distress caused by Big Tech, have come to see opinion as a way to make their business work.

“Opinion” is many things, and its distinction from “news” is often murkier than journalists are wont to admit. It’s impossible to write a story without making judgments. When the United States was a young country, the press was garrulous, robust, and overtly opinionated. A nascent form of “straight” reporting began with the penny papers of the 1830s, though it did not become the industry standard until 1846, when five daily papers decided to split the cost of covering the Mexican-American War by forming the Associated Press—designed to produce articles that could run in any outlet, regardless of political orientation. The New York Times joined the group in 1851, the year of its founding; when Ochs took over, he decided to carve out his place in a crowded market by pledging “to give the news impartially, without fear or favor.” (He also cut the price of the Times to one cent when other New York papers of repute cost at least three.) It was a successful model, and over time “neutral” journalism became the norm. Newspapers fenced opinionated writing into an “editorial” page; some, like the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, experimented in the early to mid–twentieth century with the op-ed format as a place to run additional commentary and letters. Socolow told me that, at its founding, the New York Times op-ed page aimed “not to tell people what to think, but to tell them what to think about.”

CNN debuted in 1980, igniting the twenty-four-hour news cycle and airing political debates on Crossfire and The Capital Gang. The networks had pundit-fests, too—disagreement as entertainment. Eric Alterman, in his history of punditry, Sound and Fury (1992), writes that the mainstream opinion class comprised “a tiny group”—about two or three dozen people writing for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and the newsweeklies, then appearing on TV. To be included, one needed the right job or the ability to excel at “conflating one’s career as former secretary of something or other with a healthy dose of self-promotional talent.”

In 1987, under President Ronald Reagan, the Federal Communications Commission repealed the Fairness Doctrine, which had required broadcasters to devote airtime to controversial matters of public interest and to reflect contrasting views. Now TV and radio hosts were free to pontificate unchecked. The next year, Rush Limbaugh, a former DJ, premiered his nationally syndicated talk show. AM radio, which had been a struggling business, found a lifeline; by 1993, Limbaugh was on six hundred and ten stations, reaching seventeen million listeners per week. Limbaugh—and his legions of imitators—painted the reality-based press as a biased liberal organ. “Rush is coming along as a partisan, and he’s saying, ‘I’m the objective voice,’ ” Brian Rosenwald, the author of Talk Radio’s America (2019), told me. “What they did,” however unintentionally, “got rid of any sense that there was one unified gatekeeper and challenged the idea of objectivity. They pushed us into silos.”

Then came the internet. The Drudge Report and Salon appeared in 1995. Slate, 1996. In 1997, when MSNBC.com, one of the largest news distribution sites in the country, introduced some of the first mainstream news blogs, Brown, who was the site’s editor, observed how, in the internet age, space was not a constraint. Opinion pieces, which cost little, proved to be ideal filler. “We can actually give space, if you will, to new voices that print never could,” he said—voices that would appeal to different segments of the market, pulling in readers whom major news organizations hadn’t reached before. Google was founded in 1998, making those opinions easier than ever to find. Outlets’ audience sizes were poised to expand, but digital advertising rates amounted to a fraction of what they were for print, so large publishers mostly left those crumbs to the growing number of upstarts attempting to break through. Talking Points Memo, 2000. Gawker, 2002. Facebook arrived in 2004.

In 2005, at the spring meeting of the American Society of Newspaper Editors (now known as the American Society of News Editors), in Washington, DC, Rupert Murdoch, the founder of News Corp, gave an address. He told his colleagues that they were being “remarkably, unaccountably complacent” in the face of the digital revolution. “Like many of you in this room,” he said, “I grew up in a highly centralized world where news and information were tightly controlled by a few editors, who deigned to tell us what we could and should know.” Young people, he explained, were “no longer wedded to traditional news outlets or even accessing news in traditional ways.” He cited a report by Brown, published through the Carnegie Corporation, that found that people between the ages of eighteen and thirty-four were increasingly using the Web for news consumption; just

9 percent described newspapers as “trustworthy”; 8 percent found them “useful.” Murdoch concluded, “They want a point of view about not just what happened, but why it happened,” and “they want to be able to use the information in a larger community—to talk about, to debate, to question, and even to meet the people who think about the world in similar or different ways.”

The next month, the Huffington Post went live. Headed by Arianna Huffington—a writer, socialite, and former California gubernatorial candidate—the site was conceived as a liberal response to Drudge, with a splashy homepage full of stories cribbed from legacy publications. Huffington brought in Jonah Peretti, a former scholar at the MIT Media Lab, who coined the term “contagious media.” Under Peretti, the staff constantly monitored Google and generated stories tailored to show up in popular searches. Huffington also leaned on opinion pieces, by celebrities she knew (George Clooney, Deepak Chopra, Nora Ephron) and anyone else who had something to say. Those submissions were unpaid, tremendous in volume, and highly clickable. “Opinions are essentially a form of rewrites,” Vijay Ravindran, a former chief digital officer at the Washington Post Company, told me. “Opinion is the easiest way to create breadth of content and then build the machine around that to get traffic.”

In 2006, as a side project, Peretti began working on what would become BuzzFeed. (“Originally, BuzzFeed employed no writers or editors, just an algorithm to cull stories from around the web that were showing stirrings of virality,” a profile in New York magazine explained.) The same year, Twitter launched and Facebook debuted its “share” button. Even if legacy publications didn’t yet want to believe it, the power of influence was shifting to those who best understood how to exploit the emerging technology. In 2007, the first iPhone shipped, signaling a new era of obsessive social media consumption; the following March, Facebook hired Sheryl Sandberg, from Google, to help the company grow. And soon it was the fall of 2008, when the Great Recession pushed print media’s advertising revenue off the side of a steep and deadly cliff.

“ ‘Thoughtful commentary’ on the day’s news is almost an oxymoron.”

Between 1999 and 2009, weekday newspaper circulation dropped by nearly ten million. In the first six months of 2009, more than a hundred newspapers shuttered; ten thousand newspaper jobs were lost. The New York Times was more than a billion dollars in debt. Increasingly, people were accessing the news not through traditional outlets, or their homepages, but by using search engines and social platforms. Facebook introduced the “like” button, making it possible to track what individuals were reading and to determine which posts to display prominently in news feeds. The effect on publishing, which until now had coasted on brand advertising, was severe. Digital advertising for newspaper websites “collapsed,” Ravindran said. “Facebook and Google had way more inventory and better targeting because of the amount of data they were working with.”

Publishers began to invest in trying to reach people—how to get shared and liked—and thus earn a cut of social media’s direct-response ad revenue. The most obvious strategy was to produce more stuff; the simplest way to do that with a dwindling bank account was to minimize reporting costs. BuzzFeed continued to develop virality algorithms (in 2010, the site’s most popular post was “Watch Miley Cyrus Take a Bong Hit”); the less sophisticated outlets commissioned pieces of interpretive analysis. Newspapers, seeking to distinguish themselves from the aggregators, began encroaching on the territory once held by the newsweeklies, which in turn drove more magazines into the chase for relevance, with commentary an obvious route. Opinion writing made sense editorially—it seemed a natural fit for the Web—as well as financially. “A huge factor in this is budget,” a longtime magazine editor told me. “Reporting is expensive, and it is just not as expensive to publish opinion writing.” More and more takes went up, in pursuit of clicks; by mid-2010, Facebook had five hundred million users. “If your most fiery opinion story got a ton of page views, that was considered a huge success and that would help you drive up advertising rates,” Megan Greenwell, now the editor of Wired magazine’s website, said.

But even as publishers came to understand the dynamics of social media, that wasn’t enough to sustain a newsroom. In 2011 and early 2012, ten major papers, including the New York Times, erected paywalls; several hundred smaller outlets did the same. Between 2011 and 2013, the number of visitors to the Times homepage plummeted from more than one hundred forty million to around sixty million. By then, more than a billion people were on Facebook, which changed its algorithm to emphasize journalism in the news feed. Jeff Bezos bought the Washington Post and expanded its digital presence. Every media outlet was now eagerly feeding the beast, yet it was clear that the revenue trickling in from direct-response ads couldn’t replace brand marketing. “You can’t think about editorial product in isolation from technology and business,” Kinsey Wilson, the former editor for innovation and strategy and executive vice president of product and technology at the Times, told me recently. “It doesn’t mean that you violate ethical norms, that you allow business to have undue influence over your editorial product. But there has to be a level of coordination.”

In June 2014, the Times introduced NYT Opinion, a stand-alone subscription and app that offered access to opinion coverage (including editorials, columns, op-ed pieces, and “Op-Docs”) along with additional features like Q&As in which writers responded to reader questions and comments. NYT Opinion also offered commentary from elsewhere around the Web, curated by Times editors. The idea was to draw an audience that wanted to read more than the ten free articles available per month, and liked opinion, but who weren’t yet ready to commit to a full Times subscription. (NYT Cooking went live around the same time.) But it was a short-lived experiment, discontinued just four months after it began. NYT Opinion “hasn’t attracted the kind of new audience it would need to be truly scalable,” the bosses wrote in a memo to staff. Ben French, who held various product roles at the Times, told me, “The truth is, what we found is that people didn’t really want to just buy a chunk of our coverage. It needed to have some utility and some sense of purpose, and opinion sitting by itself—you want to be able to read a news story and then read an opinion story about it.”

The next fall, the Times decided to commit fully, announcing that it would pursue a subscriber-first business strategy aimed at multiplying its “deeply engaged” digital audience. The hope was that, if the Times could double its digital revenue by the end of 2020, the newsroom would be in healthy enough shape. The opinion section—a place to experiment ambitiously with voice and subject matter, where columnists could forge lasting connections with their followers—was a promising department for growth. “If you go back to the idea of the habitual reader, opinion columnists are precisely the kinds of writers who attract repeat visits and drive habitual behavior,” Wilson said. To lure new subscribers, the consensus was that the Times would need a greater variety of opinion contributors. “People should see themselves reflected in the Times,” Tyson Evans, a senior editor for opinion product and strategy, told me. “I think opinion is a pretty powerful place to do that at scale, quickly and effectively.” No matter whether a newsroom was chasing virality or subscriptions, it seemed, commentary was king.

The 2016 presidential election was rough. Afterward, amid widespread criticism that Facebook had allowed itself to be used as a vehicle for Russian meddling, the company quietly began tinkering with its algorithm to de-emphasize posts from media outlets. In 2017, Facebook-driven traffic to media companies dropped by 15 percent. At Slate, between January 2017 and May 2018, traffic from Facebook fell by 87 percent. By then, for the first time, more Americans were getting their news from social media than from newspapers. “We’ve all been buffeted by the changes and the force of the algorithms, and the force of competition,” David Shipley, who heads Bloomberg Opinion, told me.

But the New York Times was doing okay. Bennet, who had been hired in 2016, was tasked with expanding the opinion section’s domain. Donald Trump’s victory—and the shortfalls of the Times and other news outlets in covering the story—led Bennet to a conclusion about the political orientation of his writers: “There wasn’t really an advocate for the Bernie Sanders view of the world formally in our pages,” he told colleagues at a staff meeting. “And we’ve had fewer voices to the right for quite some time.” He hired Lindy West, an author who contributed to Jezebel; Michelle Goldberg, a former writer for The Nation; Bret Stephens, a Wall Street Journal conservative skeptical of the climate crisis; and Bari Weiss, another Journal expat, who has a Zionist focus. (The Intercept observed that the additions “hardly” brought diversity to the editorial page.) The new columnists spoke to specific audiences that the Times—through data analytics and interviews with demographic groups, as well as a general envy of the Journal’s hold on conservative readers—had deemed promising subscriber targets. By December 2017, when it was announced that A.G. would be made publisher, the Times story covering the news declared, “With 3.5 million paid subscriptions (2.5 million of them are digital-only), The Times is one of the few newspaper companies whose newsroom is growing at a time when the industry is struggling.” The opinion section was producing less than 10 percent of the Times’ total output, yet opinion pieces represented 20 percent of all stories read by subscribers—which meant that the takes were punching well above their weight.

The subscriber model attracted more believers, with commentary an inexpensive way for an outlet to assert its value and build customer loyalty. The Washington Post launched a global opinions section, hiring a slate of new columnists to weigh in on international affairs; after that proved successful, the Post hired a half dozen more, running an additional page of opinion in its print edition three days a week. A Post spokesperson told me that opinion has accounted for “some of the top subscriber-converting content from the newspaper.” In March 2018, The New Yorker announced its intention to double its paid circulation, to more than two million, and hired more writers who could chime in online with their thoughts about American democracy, “Insta-celebrity engagements,” and everything in between. Editors talked less about virality and more about the number of minutes readers spent with each article. “In the time I’ve run newsrooms,” Greenwell told me, “deeper engagement is certainly what’s strived for and certainly what business partners—whether they’re advertisers or sponsors of some sort—seem to care about.”

Still, consciously or not, social media remained an important factor in everyone’s judgment. “You look at the Twitter competition for followers among pundits—it’s intense,” Brown told me. “In the world of punditry and opinion, it drives things. Writers are hired, and raises are given, based on Twitter engagement. It’s in many ways defining.” Plus, there’s fomo. Having adapted to a relentless pace, it now feels impossible to drop out. “There was a time when the president was giving his acceptance speech at the convention on a Thursday night, the editorial board would listen, and on Friday morning they would meet and discuss it; somebody would write an editorial, the editor would edit it, and we would publish it thirty-six hours later, on Saturday morning, and that would be fine,” Hiatt said. “If I did that now, I’d be a laughingstock. It’s gone from No, we have to be in the next morning to If we’re going to have a response, we have to have a response that night.”

When opinion writers publish pieces that contrast with facts reported by journalists under the same banner, staffers have little recourse. Vox argued that, in the Bennet era, opinion had “elevated trolling the Times’s liberal readership into a kind of raison d’être.” Opinion is separate from the newsroom—Bennet reported directly to A.G.—but most readers have never made that distinction. “Does op-ed care at all about how its actions affect the newsroom whose legitimacy and sweat it trades on in order to sling hot takes?” a Times staffer complained. “It’s not clear that they do.” Even within the paper’s opinion section, Bennet’s sense of mission differed from others’—and the Cotton piece proved how far apart they were. There was a feeling of being “disempowered in ways that may have prevented this from happening,” a Black employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told me. “Of all the people in opinion who could’ve read it, there were no people of color who did a first read. James didn’t find it important enough to read.” (A Black photo editor had voiced objections that went unheeded.)

The Cotton op-ed was so offensive that Times employees were moved to act; a Twitter campaign, created by Black staffers and amplified by colleagues, protested the piece. An apologetic editor’s note was appended to the top; Bennet was replaced. A.G. managed, mostly, to ride out the uproar—vowing in meetings, emails, and calls to make a lesson of the op-ed fallout. Dean Baquet, the executive editor, said he felt proud of how members of the newsroom banded together to stand up for what they believed. (Though they had all tested the limits of the company’s social media rules, no one seems to have been punished; there was strength in numbers.) What, exactly, the Times learned from the episode remains uncertain, however. To what extent did the editor who shepherded the Cotton piece, a young man who’d come from the Weekly Standard, believe that he’d be rewarded for delivering virality? Where did the leaders of the Times set their limits on opinion—and where will they, in the days ahead? In October, with Bennet long gone, the Times published yet another stinker: an opinion piece by a Chinese apparatchik advocating a crackdown on protesters in Hong Kong.

Budget-wise, the outlook is clearer: the New York Times met its ambitious digital revenue goal a full twelve months ahead of schedule. Today, with more than six million subscribers, it’s safe enough, one might infer, for A.G. to commit to diminishing the opinion output to protect the reputation of the Times. (BuzzFeed is now in the more difficult position; in the past two years, hundreds of employees have been laid off, and Peretti told the remaining staff that he hopes to keep 2020 losses below $20 million.) “Trying to publish hot takes that go viral on Twitter for being most outrageous is sort of a sucker’s game,” Ben Smith—the former editor in chief of BuzzFeed News, now a media columnist for the Times—told me. “It always struck me as an unsustainable thing. Brands are defined by their highest-profile work, and if it’s a bad take, that’s a problem.” He added that “places still tend to be defined by their opinion writers, even if they are doing less of it.”

It occurred to me, as I surveyed the world of takes, that John B. Oakes would be satisfied—there is no question that we now have “diversity of opinion,” which he called “the lifeblood of democracy.” Nobody is worried anymore about a lack of published thoughts. The problem today is democracy, and making sure the opinions that circulate are those that serve it.

Adam Piore is a longtime CJR contributor and the author of The Accidental Terrorist, The Body Builders: Inside the Science of the Engineered Human, and, most recently, The New Kings of New York: Renegades, Moguls, Gamblers and the Remaking of the World’s Most Famous Skyline.