A tour with Kyle Kajihiro wasn’t going to happen. Since the nineties, Kajihiro, a fifty-six-year-old activist and PhD candidate in geography at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, has, along with a colleague named Terrilee Keko‘olani, run demilitarized tours of O‘ahu. Called “DeTours,” they offer an alternative to the glossy experiences advertised in the travel sections of newspapers and magazines and in the guidebooks that line the shelves of “World” departments at bookstores. The tour is entirely different from the fantasy that was sold to me from the moment I arrived at the Hawaiian Airlines terminal at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport one morning in December, when I was greeted at bag check by airline employees wearing leis and saying, in Queens and Brooklyn accents, “Aloha!” On board, automated videos about flight safety were interspersed with messages from airline employees telling tourists that they and the people of Hawai‘i were eager to welcome them, that they were happy to share their special place.

Kajihiro, who has a gray beard, cropped salt-and-pepper hair, and wire-rimmed glasses, had a different attitude. The DeTours, he told me at his office on campus in downtown Honolulu, are meant to puncture a tourist’s sense of entitlement and focus instead on the land and people who were in Hawai‘i first, whose lives and cultures and histories have been transformed by outside interference.

Born and raised in Honolulu to a fourth-generation Japanese family, Kajihiro moved to Oregon for college and lived there for fifteen years before returning, in 1996. Back home, he came to observe something he hadn’t noticed as a child. Visitors—including academics and activists, politically progressive people he considered friends—were weird about Hawai‘i. “Something switched off in their brains,” he said. “They became sort of like giddy teenagers and they just thought of Hawai‘i as a playground.” It troubled him. He wanted to show them there was more to his home than vacationing on the beach. “So that was one of the things that we tried to address, the discourse of tourism,” he explained. “How does it mask the violence of colonialism and militarization in Hawai‘i?”

In the beginning, Kajihiro sought to expose visitors to the history of the sovereign Hawaiian Kingdom, including its overthrow, in 1893, by white American businessmen with help from the Marines. He wanted visitors to understand the struggle of Native Hawaiians to recover their land and assert their right to practice their culture. He hoped to introduce outsiders to local people and to build lasting connections that would subvert an industry predicated on “escape.” By 2004, the tour was formalized. Today, it focuses on four stops: ‘Iolani Palace; Camp Smith, the headquarters of the United States Indo-Pacific Command; Pu‘uloa, referred to in English as Pearl Harbor; and Hanakēhau Learning Farm, in Waiawa. “We don’t have a website,” Kajihiro said. “There’s no regular schedule. If we do it at all, it has some intentionality of what we’re going to do and why.”

I had found him after reading a book that borrows the “DeTours” name, a collection of essays called Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai‘i (2019). It aimed to counter a historically colonialist narrative that has shaped Western ideas about Hawai‘i for centuries. But there was a problem: since the book’s publication, Kajihiro had been inundated with requests, many of them from travel writers who now knew of his operation. The sudden interest gave him pause. “It’s this incessant nature of capitalism to always commodify and fetishize everything,” he said. “Even a tour like ours is now seen as something that people want to consume. And now it’s become a thing, this dark tourism.”

In a sense, it was nice to hear that readers wanted to explore the inherent power imbalance between tourists and the toured. “But people want to come here, and now that they know that there’s some problematic aspect of tourism in Hawai‘i, they want to come here guilt-free,” Kajihiro went on. “They want permission in some way. And they see our tour as being a way to give them permission.” It made him uneasy. “I don’t know quite what to make of it, or how we deal with it. That’s the crucial problem, that Hawai‘i is seen as something that’s for somebody else. To play, extract pleasure, experiences, memories, from this place. It’s never about how you come and why and what you bring.”

His point lingered heavily in the air between us. I spent half my childhood on O‘ahu—I’m an apologetic Army brat—and I have come to view the American presence on the island as a pyramid of destruction. At the base is the United States military, which colonized Hawai‘i with the reckless force of the world’s strongest power. The central block is capitalism: nowhere else is the uniquely hyperactive version more evident than on O‘ahu, home to 980,000 and visited last year by more than 6 million tourists. And at the top of the pyramid is the climate crisis, seen in the form of eroding coasts, furious storms, and endangered plants and animals—the same problems found around the world, in places that are the least responsible for disturbing their environment, places that have been taken over by outsiders.

Since moving to New York, I’d followed the impact of climate change on Hawai‘i. Recently, I started collecting articles published in national news outlets that purported to inform readers about the consequences of the crisis there. A story in the Christian Science Monitor, about a University of Hawai‘i report that warned of climate change’s effects on the hospitality industry, ran with the headline “How climate change could ruin your Hawaii vacation.” Another article about the same study, which was paid for by the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority, ran in HuffPost under the headline “Climate Change Will Ruin Hawaii”; it made only passing mention of local residents. Last year, the San Francisco Chronicle published a slideshow: “Stunning vacation spots climate change may destroy.” A CNN report highlighted Hawai‘i lawmakers’ attempt to codify climate change resistance into law, but framed it as a response to the threat of lost tourism revenue in Waikīkī, the beachfront of Honolulu. Never mind the thousands who live in Waikīkī and the surrounding neighborhoods. “That’s the part that’s hard about Hawai‘i,” Kajihiro said. “It’s too easy for folks to not have to engage.”

The flight from New York is more than eleven hours long. As I looked around at my fellow passengers, I wondered if people on board had wrestled with the fact that the influx of tourists means there are more cars on the road, more energy needed to power dozens of hotels and restaurants, more trash, more marine litter. I wondered if these travelers had considered the flight itself; our plane ride would produce 1.549 metric tons of carbon dioxide. As we prepared for descent, my mind fell on a memory: one of my first days of school on O‘ahu, when I saw a sticker plastered diagonally across the binder of a girl who would become my friend. It read:

we grew here, you flew here.

“Hawai‘i is seen as something that’s for somebody else. To play, extract pleasure, memories, from this place. It’s never about how you come and why and what you bring.”

The first American missionaries arrived on the Hawaiian Islands in 1820, landing at Kailua-Kona. Once Queen Ka‘ahumanu, Hawai‘i’s ruler, was converted to Protestantism, she tasked the missionaries with helping to educate her people. The missionaries began by developing a written version of their language, and they introduced the islands to the printing press.

Some seventy Hawaiian-language newspapers entered into circulation. For a while, because the printing presses were owned by white settlers, the papers reflected the views of missionaries; articles espoused the virtues of Protestantism and preached about the dangers of Hawaiian culture. By 1856, however, media in Hawai‘i had splintered. Henry M. Whitney, a businessman son of missionaries—who pronounced Native Hawaiians “inferior in every respect”—founded the Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Around the same time, a group of Hawaiian nationals began printing a paper of their own, Ka Hoku o ka Pakipika. It was helmed by David Kalākaua, a future monarch who would become known as the “editor king.”

Hawai‘i was then entering the final phase of its sovereignty. King Kalākaua expanded the region’s sugar industry by signing the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 and pursued a controlled form of tourism to elevate his kingdom’s international prominence—a goal foisted on him by missionaries. It was Kalākaua who built the opulent ‘Iolani Palace, in 1882. But shortly after his death, followed by his sister’s ascent to the throne, a group of insurgents waged a coup d’état that ended the Hawaiian dynasty. A provisional government, known as the Republic, was established, led by white Americans. (At the top was President Sanford Ballard Dole, as in the bananas.) The US annexed Hawai‘i as a territory, and eventually, despite protest, it became a state.

The overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom by white settlers transformed the nature of local tourism and its depictions in media. Hypersexualized images of topless Native Hawaiian women dancing hula adorned postcards that visitors could send home. Newspapers ran ads with the unsubtle message that Hawai‘i was an empty paradise available for conquest. “Tourism was a way of inducing people to come to Hawai‘i, have sex with Native women, and maybe they’ll like it here and try to settle here,” Adam Keawe Manolo-Camp, a Native Hawaiian cultural historian, told me. The author Jack London, who spent time in Waikīkī with his wife, Charmian, wrote of their excursions on the islands, enticing other foreigners to come and make it their playground. In London’s story “A Royal Sport,” he described surfing as an exotic pastime of primitive people: “Where but the moment before was only the wide desolation and invincible roar, is now a man erect, full-stature,” he wrote, “not struggling frantically in that wild movement, not buried and crushed and buffeted by those mighty monsters, but standing above them all.”

The Republic began curtailing the rights of the Native Hawaiian press. By 1896, only fourteen Hawaiian-language newspapers were left, giving white men broad control of the narratives about Hawai‘i that circulated around the islands and spread to the continental US. Coverage reflected racist tropes and boosted the business interests of white Americans.

That included matters of the environment. The island of O‘ahu, in particular, was pillaged to make space for white settlers’ sugar plantations. Waikīkī, on O‘ahu’s south shore, had once been rural wetlands; Native farmers in Mānoa, Pālolo, and Makiki had devised sophisticated farming and aquaculture systems called lo‘i, or terraced taro farms, and loko i‘a, or fishponds, there. Streams filtered sediment before it reached the ocean. When the sugar barons came, however, much of Waikīkī was repurposed to meet their irrigation needs. Sugar, as it turned out, requires enormous amounts of water, and so it was diverted from Hawaiian farms and fishponds, displacing their proprietors. Thanks to the Reciprocity Treaty, sugar was the economic priority.

In 1904, Lucius Pinkham, president of the local board of health, began to warn that Waikīkī’s wetlands were attracting disease-ridden mosquitoes and posing a threat to public safety. Pinkham, who was from Massachusetts and had only been in Hawai‘i a few years, proposed a solution: a canal that would drain the “Waikīkī swamps” and, through dredging, raise the area above sea level to allow for construction on the land. On February 21, 1906, the Hawaiian Star ran a story advocating Pinkham’s idea. “The tide would keep the water in this lagoon in perfectly wholesome condition,” the article stated. But real estate development was the true ambition. The Star led with Pinkham’s promise of “a Venice in the midst of the Pacific.” The story went on: “The president of the Board of Health recommends that the government, by its right of eminent domain, shall in an equitable and just manner acquire ownership and rights in said district as shall enable it to transform it into an absolutely sanitary, beautiful, and unique district.” In 1915, London made a visit and wrote, “I am glad we’re here now, for someday Waikīkī beach is going to be the scene of one long hotel.”

The canal project started in 1918, by which time Pinkham had been appointed governor. Indigenous and Asian farmers largely lost their land. By 1926, the Ala Wai Canal, as it was named, was finished. The transformation of Waikīkī was well underway, complete with single-family homes, businesses, and hotels. Local newspapers encouraged development in the area; in October 1928, the Honolulu Advertiser ran a sixteen-page spread glorifying the boom. The number of tourists doubled. A travel writer on assignment in Waikīkī for Vogue wrote, “It is the most Oriental of Occidental cities, the most Occidental of Oriental; and, since it is so distant from the customary center of human habitation, the eyes of weary men turn towards it wistfully as a haven of escape from the habitual.”

Waikīkī attracted more and more attention from wealthy American tourists. The beachfront played host to a famous hotel strip. Indigenous lives were forever changed; the land and water were polluted. Eventually the environmental implications of the Ala Wai Canal became impossible to ignore when, in 1965 and 1967, heavy rain flooded two nearby streets: Ala Wai Boulevard and Kalākaua Avenue. The state cleaned up the resulting mess but dumped contaminated sediment straight into the ocean. Over the decades, as the neighborhood became more urban, the canal, plagued by runoff, became more toxic. Locals stopped fishing in it. Mercury was found in the boat harbor into which the Ala Wai led. By the time I was a teenager on O‘ahu, in the early aughts, the Ala Wai had earned a reputation for being dirty and smelly—like bad eggs—a far cry from the fancy boat race paradise that Pinkham envisioned. All the while, travel journalists continued to describe “virgin” beaches and to publish images of shorelines emptied of local people.

My own arrival in Hawai‘i was tinged with apprehension. I was thirteen, and I had already moved and changed schools seven times. I didn’t know much about Hawai‘i aside from that it was always warm and there was no winter. My mom, sensing my unease, gave me a book, a historical novel for young adults about Princess Ka‘iulani. She had been the heiress to the throne—King Kalākaua was her uncle—and she was educated in Hawaiian, Latin, French, German, and English, in the model of a cosmopolitan woman. Her kingdom was overthrown while she was spending time abroad; when she got home, she fought for Hawaiian rights. She died at the age of twenty-three, from inflammatory rheumatism. From her story, I learned that Hawai‘i had once been a different place from what it was now.

My family took a two-legged flight to Honolulu. It was the longest plane ride of my life. At the airport, we were picked up by someone from the military, who dropped us off at a hotel designated for the military. At our base, Schofield Barracks, there was a commissary and a pool and a movie theater—everything one might want. Some military families told my parents not to send me to public school. But they did anyway. My mom advised me to get involved with my classmates—and to step outside of the military bubble.

I joined track. I became a cheerleader. I saw that sticker on my classmate’s binder—we grew here, you flew here—and although I didn’t fully grasp its meaning at the time, I understood enough to feel guilty. My guilt wasn’t discussed. But it was part of a tension that permeated everything: there were three bases surrounding my town, and my school was about 25 percent military kids. At a nearby high school, a clash between local kids and military brats got bloody; later, we all saw the story on the news.

There was no big moment when the dynamic was explained to me. It was understood through talking it over with friends, being embraced by their families, having their families meet mine. It was a matter of building relationships and participating in my community—and not just the military one. The dynamic wasn’t explicitly discussed in classes: a course I took on modern Hawaiian history was taught by a white guy from Maui (a descendant of missionaries, I speculated); he was tall and goofy and also coached the basketball team. As I got older, I found videos of Haunani-Kay Trask, a Native Hawaiian political scientist and activist. “The Americans, my people, are our enemies,” she’d said. “The United States is a death country,” she continued. “It gives death to Native people.” I remember watching her, not disagreeing, and thinking: I should not be here.

Recently, a friend asked me about going to Hawai‘i. She had visited, had a great time, and said that she felt a connection to the islands. “How can I move there without feeling like a colonizer?” she joked. I thought about it and replied, “Just don’t.”

Waikīkī attracted more and more attention from wealthy American tourists. Indigenous lives were forever changed.

If you are a tourist headed to Hawai‘i, it is likely that you will search for stories about the places you want to visit. You will look up restaurants to eat in, browse hotels to stay in, and perhaps trawl through Yelp comments for clues as to “authenticity.” Along the way, you may find stories that warn of the threat to Waikīkī Beach, an area that generates 42 percent of the state’s tourism revenue. For years, it has been eroding, because developers built resorts and seawalls too close to the natural shoreline. You may read about how rising sea levels, a result of climate change, claim about a foot of the beach per year. Sea levels around the archipelago are expected to hit 3.2 feet by 2100; if you keep clicking around, it’s possible you could discover that, in November, the City and County of Honolulu announced it would sue fossil fuel companies for leaving some 3,880 structures on O‘ahu at risk of destruction. Or you might find the stories about those freaky king tides that engulf normally dry beachfronts. In 2017, the height of a king tide broke a 112-year-old record.

Overcrowded: Last year O‘ahu, home to 980,000, was visited by more than 6 million tourists. Pool REIVAX / TAMA / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

But you may miss the story of the ahi tuna. Poke, which in recent years has exploded in popularity beyond Hawai‘i, is a local staple, and it’s now getting harder for local people to access the ingredients. As a result of climate change, tuna have come to find the waters around Hawai‘i too warm to swim in. So they’re heading north, seeking cooler temperatures, which means that fishing fleets in Hawai‘i have to burn more fuel to reach them.

You might not realize, while on vacation from what may be very cold weather, that the temperatures around Hawai‘i are unusually high these days, especially when combined with the absence of trade winds. Over the past forty years, the number of northeast trade wind days has declined by half. That drop has led to sharp increases in commercial and residential air-conditioning costs; recently, the state installed air-conditioning units in more than half of all public school classrooms. They hadn’t needed it before.

In the past several decades, O‘ahu has lost 25 percent of its beaches. There’s an obvious impact on tourism, and on residents who live in beachfront properties. Kanaloa Bishop, a forty-year-old educator who lives in Kahalu‘u, on the eastern shore of O‘ahu, sees evidence of the climate crisis every time he drives his car. “Our house is near the ocean, and all our activities require us to move along the coast, so we are starting to see the changes—and they’re getting more drastic each year,” he told me. In the winter, he added, “You’ll notice that a lot of the road is falling into the ocean.”

Josh Stanbro, the head of the Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability, and Resiliency, told me about the cultural stakes of coastal erosion. Hawai‘i has the highest percentage of multigenerational homes of any state. (Housing costs are astronomical, supply is low, and wages are even lower.) “So you’ve got tons of people wall-to-wall in homes,” he said. “Where do they go to just blow off steam, to recreate, to hang out together, to socialize? Everybody goes to the beach.” He continued, “That’s the heart and soul of our island culture, connecting on these beaches. And you can imagine, when you have 25 percent less of them? Suddenly people are getting more and more crowded. And that begins to fray the social fabric as well.”

These stories are told in the local press. Nathan Eagle, a journalist for Civil Beat, published a multimedia story that took readers into the Maui rain forest as scientists went on the hunt for a dozen of the last surviving kiwikiu, a parrotbill that’s endangered because of a mosquito-borne illness caused by global warming. Local radio reports on how lawmakers are addressing an overaccumulation of trash around the state and greenhouse-gas-producing landfills that are reaching capacity. Hawai‘i’s editorial boards argue in favor of legislation meant to confront problems that exacerbate the climate crisis. A local television news station reports on the environmental impact of tourism. All that coverage has helped create a voting base with a high level of awareness about the effects of climate change. But visitors are, by and large, not seeing that news.

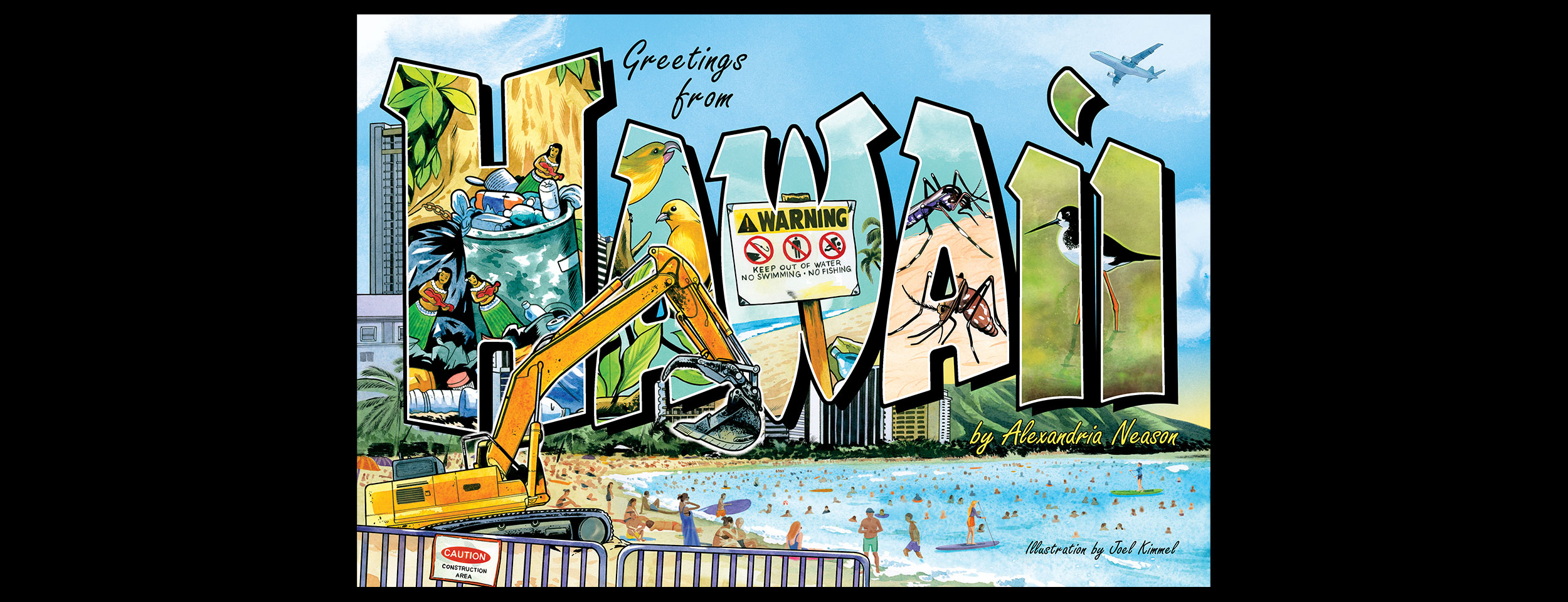

That poses a challenge to Stanbro, forty-eight, whose job is to find policy solutions that will help O‘ahu mitigate the climate crisis. When we spoke in his office, Stanbro, clean-cut, with a brown goatee and a blue aloha shirt, explained that tourists—and the powerful tourism lobby—are part of his mandate, even as they continue to exacerbate the problem. In 2015, for instance, Governor David Ige signed legislation committing the state to 100 percent clean energy by 2045 in an attempt to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Researchers determined that, on O‘ahu, on-road transportation represented the second-largest emissions contributor. Rental car companies are a major culprit. A proposed state bill would require those companies to provide electric cars, but the legislation hasn’t progressed. “From colonialism until now, Hawai‘i has always been treated as ‘You’re not really a thing; you’re a postcard, you’re a pretty place, but you’re not self-activated,’ ” Stanbro said, of how Hawai‘i is depicted in media outside the state. “The message that I think we’re trying to spin, and flip that on its head, is that we’re actually leading. And it’s a moral issue, because we know we’re going to be hit first and worst as an island community.”

For many in Hawai‘i, the Ala Wai Canal represents a convergence of the challenges—militarism, colonization, and hypercapitalism—that delivered the consequences of the climate crisis. In recent decades, it’s become apparent that the canal’s design was deeply flawed. As floods and pollution have worsened, millions of dollars of state funds have been spent on dredging and cleanup. In the nineties, the state asked the Army Corps of Engineers to devise a solution; in 2001, it released a plan. A few years later, after a 2004 flood in Mānoa caused $85 million in damages, focus shifted toward flood prevention. Since then, a series of plans have been proposed, and argued over, by state officials and Honolulu residents. “What is at stake is the economic engine of Hawai‘i, which is Waikīkī,” Representative Colleen Hanabusa said, in 2018. But homeowners worried about what would happen to their land, remembering the seizure of farms in Waikīkī a century earlier and fearing that history would repeat itself.

An appealing plan, known as the Ala Wai Centennial, has been put forth by Hawai‘i Futures, an initiative that seeks to restore the Hawaiian system of ahupua‘a. Ahupua‘a are traditional Hawaiian land divisions that typically extended from mountainous summits, down valleys, and all the way to the ocean. This land use system—the antithesis of the urbanization that has now gripped Honolulu—emerged out of a sense of responsibility to the local environment. An ahupua‘a revival could accommodate a number of flood prevention tactics and encourage shifts in human behavior necessary to combat climate change. But the Ala Wai Centennial plan gets relatively little coverage.

“Certain places and practices get sacrificed to protect the tourist industry,” Noelani Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, a Native Hawaiian associate professor of political science at the University of Hawai‘i, told me. “At one time, this ahupua‘a was a huge producer of food in terms of growing taro in lo‘i fields,” she explained, of the area around Waikīkī. “Now there are only three active lo‘i in all of this ahupua‘a of Waikīkī, and all of them would be impacted by the way that the Army Corps of Engineers has designed the Ala Wai project. We’re willing to sacrifice all those things to protect the tourist industry infrastructure. It’s just another contemporary example, to me, of those dynamics of settler colonialism: destroying one practice and way of life to replace it and proliferate another.”

Stanbro, however, considers the Ala Wai Canal to be a false flash point that plays on otherwise real tensions between local residents and tourists. Though he acknowledges the legacy of land decisions being made by people other than those who have traditionally occupied it, he sees in the canal controversy a failure of communication by the government. “There’s thousands of people that are Hawai‘i residents that live in Waikīkī,” he said. “There’s a strip of hotels, but there’s a ton of residential right behind.” The canal problem needs to be fixed for everyone’s sake, he argued. This is not Pinkham redux.

In Stanbro’s view, tourism makes climate resiliency more challenging. But he sees opportunity, too. In the Republic of Palau, an archipelago in Micronesia, the government imposes a hundred-dollar “Pristine Paradise” environmental fee on visitors. That could serve as a model in Hawai‘i, Stanbro suggested, forcing tourists to engage with the place not only as the vacation paradise they’ve read about from afar, but as a site of profound environmental consequence.

“From colonialism until now, Hawai‘i has always been treated as ‘You’re not really a thing; you’re a postcard, you’re a pretty place, but you’re not self-activated.’ ”

In 2018, the most recent year for which data is available, 9,888,845 visitors arrived in Hawai‘i by air and by ship, marking a new record. They spent $17.64 billion, an average of nearly $200 per person per day. More than 42 percent of that went to lodging costs. Some people stayed at the Royal Hawaiian, a pink palace on the beach. Others checked in at the Westin Moana Surfrider, the Sheraton Princess Ka‘iulani, or the Sheraton Waikīkī. All are owned by Kyo-ya Hotels and Resorts and operated by Marriott, the largest hotel chain on the planet. The hospitality industry, including food service, employs nearly 14 percent of the state’s workforce.

While the tourists are out, their rooms are cleaned and their meals cooked by local people. In 2018, hospitality workers unionized with Unite Here! Local 5 earned $22.14 per hour, a rate higher than that taken in by their peers at non-union hotels. But that money doesn’t go far; many in Hawai‘i work two or three jobs to make ends meet. That June, when contracts expired for Local 5 members, union leadership approached Kyo-ya and asked for a $3 raise. In contract negotiations, the union also sought protections and benefits. Kyo-ya countered with a $0.70 raise. By the fall, talks had stalled, and the union posed a question to its workers: Were they willing to go on strike?

Ninety-five percent voted yes. On October 8, 2018, some 2,700 Kyo-ya employees walked out. At five in the morning, they lined up by the entrances to their hotels wearing matching red T-shirts with a message to management in big white block letters: one job should be enough. At the Sheraton Waikīkī, while guests replenished their own shampoo, conditioner, and toilet paper from communal stations set up by management, workers picketed outside, beating drums and chanting.

Ikaika Hussey, an organizer with Local 5, walked the picket line alongside workers. Tourists, he said, responded to the strike in different ways. “Some people were incredibly supportive of the workers and would walk with us in the strike line, would give us hugs, would bring us food, and would donate money on the strike line,” he recalled. “These were people who were in town for a few days. They just spent thousands of dollars to get here. And they saw the strike as enriching their experience and not detracting from it.” Then his tone changed. “And as you can imagine”—he laughed—“there’s a lot of people who had exactly the opposite reaction. They hated us for ruining their Hawaiian vacation.”

Over coffee in Nu‘uanu, Hussey, forty-one, who has dark hair and brown eyes and wore a navy aloha shirt tucked into slacks, told me that media depictions of Hawai‘i as an oasis throw a curtain over the state’s inequities. “There’s a Hawai‘i that exists in people’s imagination,” he said. “It was guys at Disney, at the marketing departments in Waikīkī, and journalists. All these folks crafting a narrative that makes my life harder. It makes the lives of everyone here a little bit harder.”

Local 5 was on strike for a record fifty-one days before winning $6-per-hour raises, spread over four years. It was a proud time for Hussey. “So many people living here don’t have that same power, you know,” he said. Hussey had become an activist as a teenager, when he attended a meeting of the Hawaiian Sovereignty Elections Council. Soon, he started going to more political events and organizing around land demilitarization and Hawaiian sovereignty. He often found himself working as a de facto press spokesman. “A lot of times the press here is very colonial,” Hussey explained. “They would hire reporters who had no serious context for Hawai‘i history. And I would spend a lot of time trying to educate reporters.” In 2008, Hussey launched the Hawaii Independent, a site for investigative reporting and hyperlocal news that continued to publish through last summer.

When Hussey became involved with Local 5, it put him at the intersection of many problems confronting Hawai‘i residents, including the climate crisis. “I came to realize that the kind of work that we need to do in order to defeat climate change—which is an outgrowth of capitalism and colonialism—is, we need to organize within the labor movement,” he said. Local 5 has advocated climate change legislation, even when it’s not tied directly to labor concerns. Members testified in favor of a single-use-plastics ban that was signed into law in December. To Hussey, labor stories are climate stories, too.

Hussey’s spouse is Marti Townsend, the director of the Hawai‘i chapter of the Sierra Club. It’s common for them to wind up working on the same things. “She talks to her members about environmental justice and racism; I talk to my union members about environmental justice and racism,” he said. “My members are worried about it because they know that it will affect them. The rich folks are going to get a lifeboat—they’re going to go to Mars, or they’re going to live on their own private islands. And they’re not going to worry about their jobs being taken away or their houses being washed away. The rich will always be fine.”

Climate change, in Hussey’s view, is a concern of the labor class, a “violence perpetrated by capitalism.” When I asked Hussey about the narrative, often advanced by media coverage, that the tourism economy is singularly crucial to the survival of Hawai‘i—from the laborers of Local 5 on up—he balked. Tourism is a major industry in Hawai‘i, and thus newsworthy—sure. But stories that treat tourism as an inevitability, and fail to ask how it can be more sustainable, suggest that, for better or worse, we’re stuck with the status quo. “The idea of tourism as a main economic driver for Hawai‘i is an incredibly new idea,” he told me. “We’ve had an economy here for, like, two thousand years. Anyone who says that we have only this, that there is no alternative, lacks imagination.”

Climate change is a concern of the labor class: “violence perpetrated by capitalism.”

On my last day on O‘ahu, I set out to drive part of the route of Kajihiro’s tour. Though he said he couldn’t take me out himself, he’d offered—with some skepticism, I sensed—to give me notes on where he takes visitors. It was a warm day, at least eighty degrees. The sky was cloudless. I got into a rental car in Makakilo, my old neighborhood on the west side, and headed east, toward downtown.

I was headed for ‘Iolani Palace, on South King Street. Over the years, the palace has been painstakingly restored and cared for, as a reminder that the state of Hawai‘i was once a kingdom. When Kajihiro brings visitors here, he describes it as a living symbol of sovereignty, but also the scene of a crime. The palace, now a museum, is enclosed by a green gate and framed by manicured lawns. I drove in and parked, as I had done many times before, to remember Queen Lydia Lili‘uokalani, who was locked in a room here while white men stole her country.

Kajihiro had told me to check out the southeastern corner of the lawn, where I hadn’t spent much time. The palace was decorated for the holidays: red, green, and white lanterns were strung across its balconies. Out in front of the stairs, two tourists wandered, posing for photos. I kept walking and found what I’d come to see: a small stone structure framed by leafy flora the color of rubies. It was a shrine, built in 1993, the hundredth anniversary of the kingdom’s overthrow, made from stones that Native Hawaiians had brought from their homes. The stones were arranged in a cube, as if constructing a foundation, about two feet tall. Leis dried out by the sun were placed on top. A tiny Hawaiian flag, flown at half mast, was at the center. On tours, Kajihiro stops here to review the long history of Hawaiian resistance to colonization.

The second stop on Kajihiro’s tour is Camp Smith, the headquarters of the US Indo-Pacific Command, atop a steep hill in Halawa Heights with views of Pearl Harbor, the crux of militarization on O‘ahu. To get there, the tour passes by Kapūkaki, or Red Hill, where the Navy buried storage tanks now leaking jet fuel into the ground near the island’s main drinking-water supply—which poses a major problem, if climate-crisis-induced storms hit and cause an accident that pollutes the water.

At the top of the hill, Kajihiro and his guests get out of their car. Along the eastern side of the road is fencing that separates the military base from the rest of the neighborhood: houses crowded together, as though clamoring for space. Here, Kajihiro tells the story of John Schofield—the general for whom the base of my childhood was named. In 1873, he was sent to sovereign Hawai‘i on a secret mission under the cover of tourism, to scope out a spot for the naval base that we now call Pearl Harbor. When I arrived at the main gate, I was denied access without a military escort.

Instead of driving away, I pulled my car to the side of the road and got out, climbing to the top of a short rock wall enclosing the base. Before me, the valley spread far into the distance. I could see Pearl Harbor, the next stop on the tour. All around me was evidence of that destructive pyramid: militarism supporting capitalism that’s driving climate change.

For decades, Native Hawaiian activists have sought, through protest and legal action, to demilitarize their homeland and restore its environment. As I drove down the Leeward Coast—past Ko ‘Olina, a series of man-made lagoons surrounded by four major resorts, including the Four Seasons and Disney’s Aulani—I thought of my conversation with Hussey. He’d asked me, “Who is Hawai‘i for?” Was it for the people who live here? For the military? For the tourists? Climate change puts everyone at risk. The question of how to confront the crisis will be a matter of whose story is at the forefront, whose survival is deemed the most important. Zigzagging across O‘ahu, I saw dozens of Hawaiian flags, fluttering off the back of pickup trucks, flown in front of homes, and hanging from tents at beach parks. Often, the flags were upside down, signifying distress.

When I spoke with Hussey, he said that, even though the members of his union work in the tourism industry, they care more about an economy, and an environment, that can outlast it. “I think the winning move is for us to allocate our climate change dollars to restoring the economy that has sustained Hawai‘i for centuries,” he told me. “We focus on feeding our people, housing our people, educating, enlightening our local folks. That has to be our number one priority.” It’s a mindset that is more about sustainability than temporary visitors. It may never show up on a travel site. But it’s the one that asserts, clearly, who Hawai‘i is for.

Alexandria Neason was CJR’s staff writer and Senior Delacorte Fellow. Recently, she became an editor and producer at WNYC’s Radiolab.