When George Horace Lorimer took over as editor of the Saturday Evening Post, America was a patchwork of expat communities. Memories of the Civil War still cleft the nation; European Jews, Irish, Italians, and Chinese immigrants lived in separate enclaves. The Germans and Scandinavians were already out farming the Midwest. There was no real sense of nation or unity.

The Post was founded in 1821 and printed in the former office of Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette, which had ceased publication. Cyrus H.K. Curtis bought the Post in 1897, when circulation had stalled at two thousand readers. He was determined to publish stories he said Franklin would have chosen himself: “practical, moral, humorous, inventive.” He hired Lorimer to be the Post’s literary editor in 1899. Lorimer accepted, with one caveat: “I’ll spend your money, you’ll ask no questions.”

The first edition of the Saturday Evening Post, published in 1821. © SEPS

Lorimer realized there was no magazine on the market that could reach the entire nation. Ladies Home Journal was the great success of the day; the Post, Lorimer said, would be the same for male readers—everything the aspirational, well-rounded businessman ought to know, delivered weekly. Lorimer believed the country yearned for a unifying identity. Fireside chats lay three decades away; America needed the Post.

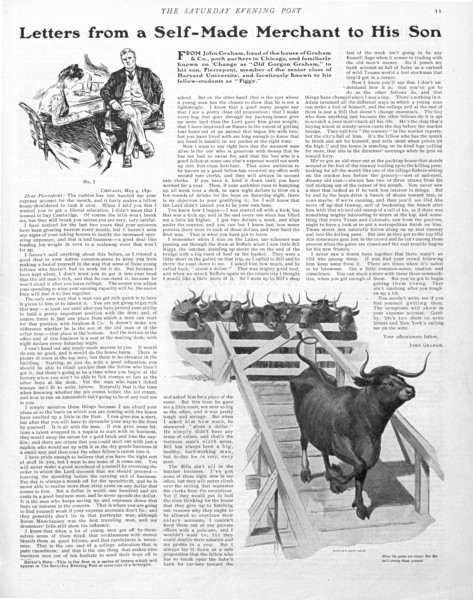

What Americans shared, Lorimer decided, was the desire to get ahead. In 1903, he launched “Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son.” The column was a series of missives from a fictional business tycoon to his heir. Lorimer wrote in the voice of the wealthy father the Post’s aspirational readers may not have had. Here was a path for new Americans to understand their country and achieve success.

“Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son,” Lorimer’s popular column. © SEPS

Lorimer aimed to prime his readers for success with top-quality, accessible content. In interviews over the years, Albert Einstein himself explained relativity in lay terms to a Post correspondent. Edward Teller told about the H-bomb. Thomas Edison bemoaned the loopholes in patent law.

Lorimer was a quick reader and a decisive judge of talent. He was determined to steer clear of what he called the “big name fallacy.” He ran a small block ad in the back of the magazine: “Good short stories bring good prices.” The pitches poured in. Each night, he would grab a stack of unsolicited submissions from the slush pile to read on the train ride home to Wyncote, Pennsylvania. (He discovered Sinclair Lewis on that train.) Each week, he read a reported 500,000 words in manuscripts. The quality of the Post’s content was so high that soon, female readers were just as plentiful as male.

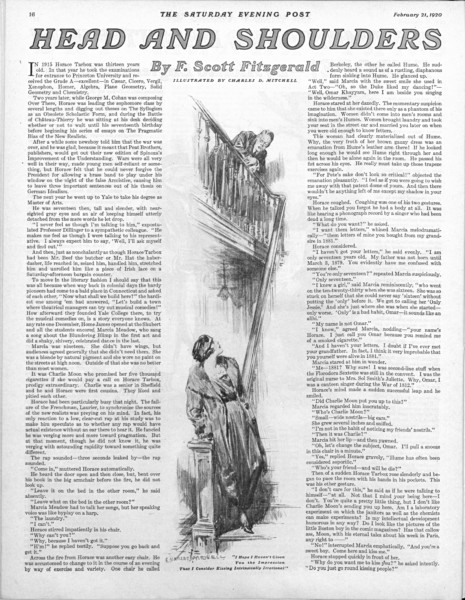

An early story by F. Scott Fitzgerald, which ran in the Post a month before his debut novel, This Side of Paradise, was published. © SEPS

When Lorimer accepted a submission from F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1919, Fitzgerald was an unknown. This Side of Paradise had sold but had not yet been published. Readers loved Fitzgerald—he went on to publish sixty short stories with Lorimer. By 1929, the Post paid him $4,000 a story, equivalent to roughly $59,000 today. Ernest Hemingway teased Fitzgerald for writing fewer novels than he should, in favor of easy money from the glossy magazines he called “The Slicks.” (Hemingway, who wanted to separate himself from fiction trends of the time, claimed never to have submitted his own work to the Post.) Lorimer famously made Rudyard Kipling, already a star, propose six stories before he accepted one. His high standards did not mean he shied away from writing he disagreed with: in 1936, Lorimer published a series of essays on money by Gertrude Stein that equated unemployment with laziness and ignored the harsh impact of the Great Depression.

Lorimer’s strategy ran up almost a million dollars in debt at first, but the plan worked. Ten years later, in 1909, the Post had a million subscribers. By 1919, there were two million. When Lorimer left, in 1936—he could no longer edit a magazine for a country that had put Roosevelt in office, he said—readership was at three million, and the staff had to generate extra editorial material to wrap around all the ads.

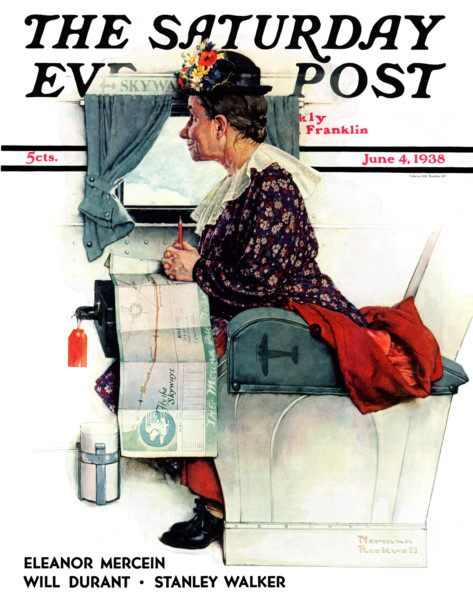

“Airplane Trip or First Flight” (1938) by Norman Rockwell. © SEPS

The Post’s best-known alliance is with the artist Norman Rockwell, who, in 1916, at age twenty-two, walked into Lorimer’s office with some canvases under his arm. Lorimer bought three on the spot. Rockwell painted more than three hundred of the Post’s three thousand–plus covers, locating in his images a space somewhere between what it meant to be American at that moment in time and what Americans longed to be. Rockwell’s art pervaded visual culture for generations of Americans; Steven Spielberg, who collects the covers, called them “little movies unto themselves.”

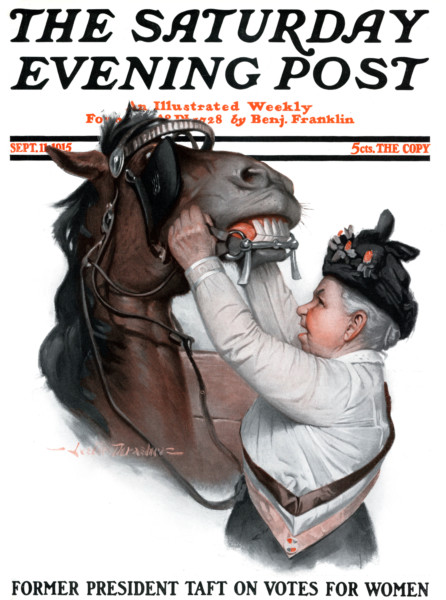

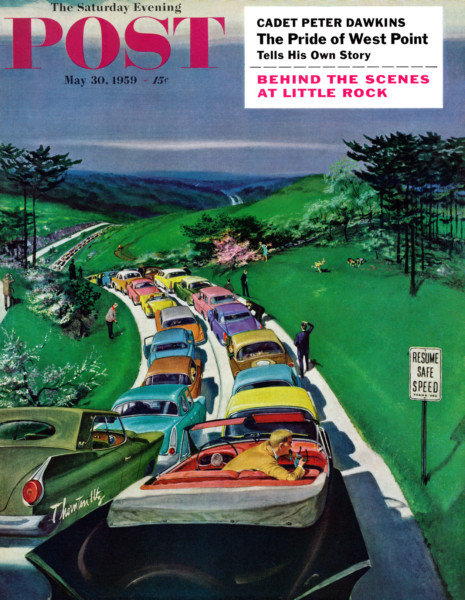

The images were gently wry, a suggestion of small-town America. But Post covers weren’t just baseball diamonds and soda jerks. They reflected the evolution of American culture. As cars became ubiquitous, there were covers of weekend traffic jams on country roads. The Post’s covers depicted a suffragette bridling a stubborn horse; the upward spike in parenting books and child psychology; a Native American receiving junk mail offering the chance to “See America First”; marriage proposals and maternity wards after World War II.

The fight for women’s suffrage, front and center in “Bridling the Horse” (1915) by Leslie Thrasher. © SEPS

“See America First” (1938) by Norman Rockwell © SEPS

“Leaving the Hospital” (1949) by Stevan Dohanos © SEPS

“Resume Safe Speed” (1959) by Thornton Utz © SEPS

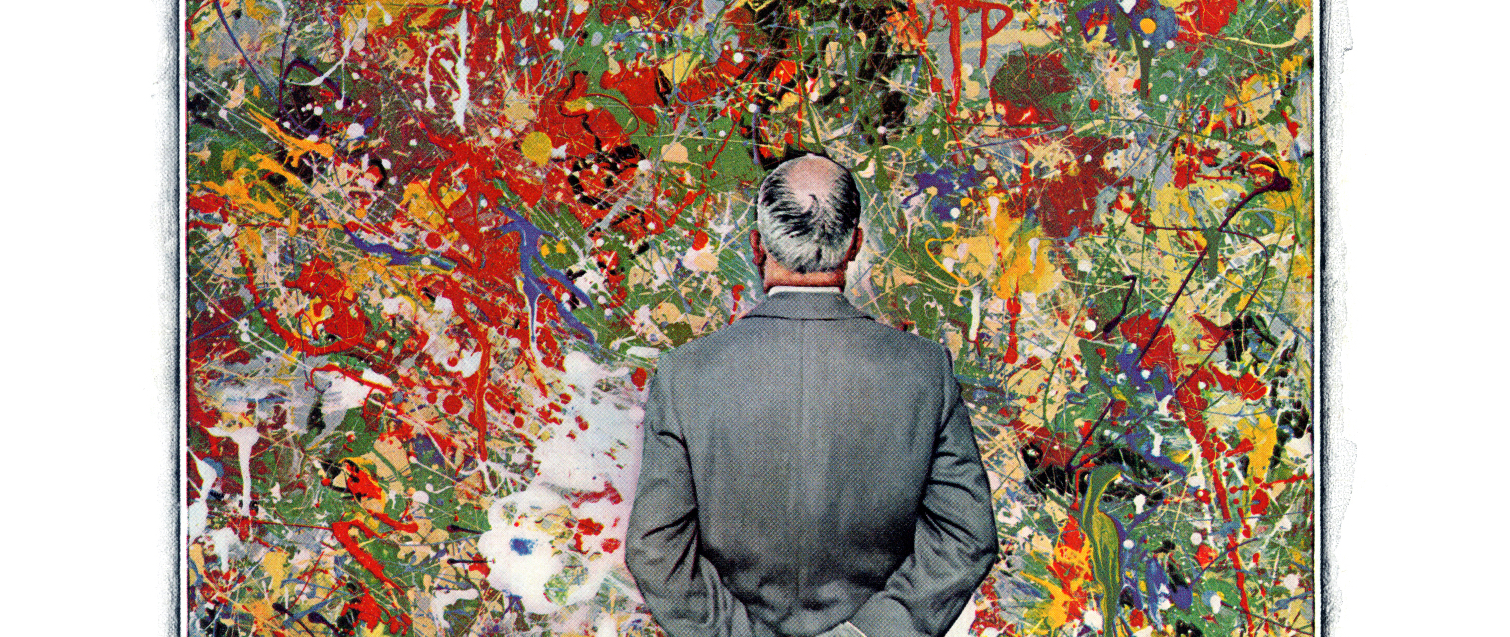

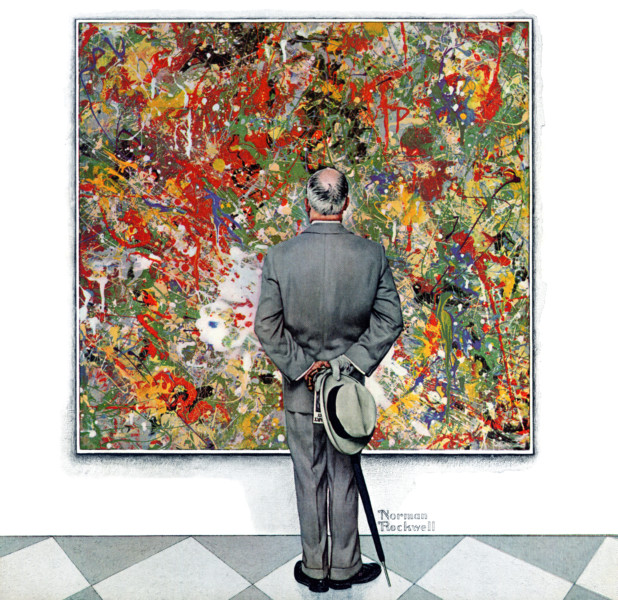

In 1962, the Post ran a Rockwell cover of a gray-suited businessman, back to the viewer, staring down a Pollock-esque canvas. The painting is an explosion of chaos, inches from his face. That was the year the Supreme Court struck down mandatory prayer in public schools, Bob Dylan released his debut album, and Helen Gurley Brown published Sex and the Single Girl. The businessman clasps his fedora behind his back and slouches slightly to one side—his posture an articulation of his generation’s what-the-hell-is-this moment. “Rockwell out-Pollocked Pollock,” Steven Slon, the Post’s current editor, says.

“Art Connoisseur” (1962) by Norman Rockwell © SEPS

One American aspiration is particularly hard to chart in the Post’s archive of covers: the civil rights movement. The racism of American media from that era was more ubiquitous; Black Americans rarely featured on the covers of periodicals read widely by white Americans. When Rockwell eventually left the Post, in 1962, plenty claimed it was because he wanted creative freedom to cover the more polarizing political subjects the Post had traditionally avoided. In a 1971 interview with the New York Times, Rockwell was quoted as saying, “George Horace Lorimer, who was a very liberal man, told me never to show colored people except as servants.” Jeff Nilsson, the director of the Post’s archives, says Rockwell left because of the Post’s efforts to modernize with photographic covers. “[Rockwell] says in his autobiography they had asked him not to do illustrations. They only wanted him to do portraits,” Nilsson says. “So he did portraits of Bob Hope and Jack Benny and Nehru and the presidential candidates. But he didn’t want to just do portraits. So he decided he was going to move on.” His best-known civil rights image, “The Problem We All Live With”—an oil painting depicting six-year-old Ruby Bridges as US Marshals escort her to her first day at an all-white school in New Orleans—appeared in Look magazine in 1964.

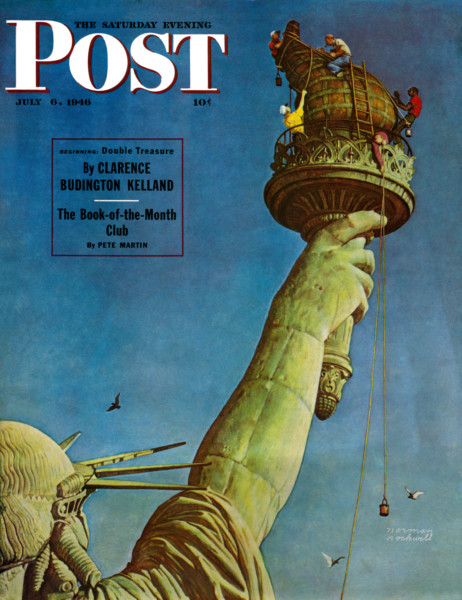

“Working on the Statue of Liberty” (1946) by Norman Rockwell © SEPS

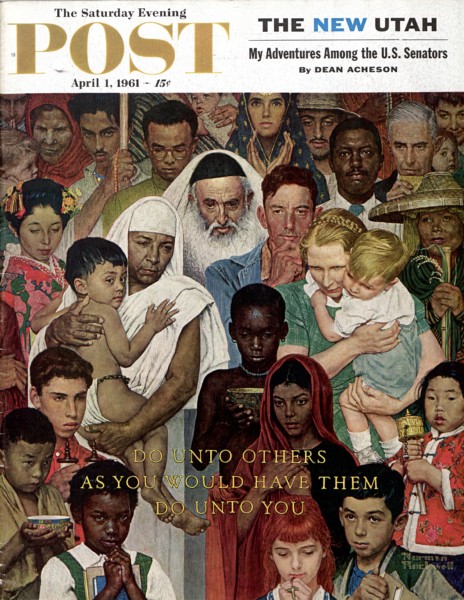

Occasionally, Rockwell’s efforts to include Black Americans in the Post surface in the archives. A 1946 cover depicts four men polishing the Statue of Liberty’s torch. Reference photos used as models for the painting, now held at the Norman Rockwell Museum, show that Rockwell changed one of the men from white to Black. “The Golden Rule,” a 1961 cover, includes among its subjects, who represent a range of racial, ethnic, and religious identities, a young Black girl clutching two schoolbooks—a clear allusion to Bridges, whose first day of kindergarten that fall would still have been fresh in readers’ memories.

“Golden Rule (Do unto Others)” (1961) by Norman Rockwell © SEPS

The Post’s circulation peaked in 1960, when it topped 6.5 million. In 1969, however, the magazine briefly closed. Financial troubles had mounted over the years. Curtis made some unlucky investments in paper mills. Radio, and then television, had proved tough to compete against. A defamation lawsuit was expensive. Beurt SerVaas, an Indianapolis industrialist, bought Curtis Publishing and acquired control of the Post in 1970, with a plan to pick up Curtis’s children’s magazines Humpty Dumpty and Jack and Jill.

Rockwell stopped by the Philadelphia offices to collect some old canvases and asked SerVaas if he’d ever consider a relaunch. “Maybe, sure,” he replied. Two weeks later, Rockwell appeared on the Today show and told the country SerVaas was bringing the Post back.

The May/June 2019 issue, cover art by Shari Erickson © SEPS

In 2018, the Post launched a new website, including a comprehensive archive, dating back to 1821, of articles and covers. Today, the Saturday Evening Post Society, a nonprofit, owns the magazine. An editorial staff of twelve puts out six issues a year; circulation is roughly 350,000. There is still fiction in every issue and original artwork on every cover. Content focuses on features, of which Slon, the current editor, says 95 percent are contemporary. But to mark the Post’s two hundredth anniversary this year, Slon turned to the past, publishing roundups of the archive’s best artwork, fiction, profiles, and reporting. “Our American moment is the culmination of thousands of moments, which were collected, written, and printed in this, the oldest magazine in America,” Nilsson wrote to mark the Post’s bicentennial.

An issue to commemorate two centuries of the Post’s reported pieces includes an 1865 account of the Lincoln assassination and a prescient 1920 analysis of “sensationalism” in news media. A 1964 account of the Beatles’ victorious return from their first tour of the US sits alongside a profile of a breast cancer and heart disease screening initiative for uninsured women in Florida, and the story of a Tennessee town’s efforts to surround its immovable 1899 monument to Confederate soldiers with statues and markers depicting the suffering and advancement of Black Americans.

Reports from the archive offer a useful frame for today’s issues, too. “They are the story of modern America,” Slon says. A few years ago, coverage of the 2008 banking crisis featured alongside an older piece on the Panic of 1907 and the subsequent creation of the Federal Reserve.

His main challenge in reviving such pieces is the edit. Most contemporary magazines do not publish the ten- to fifteen-thousand-word pieces the Post ran in the 1940s. Though the days of commissioning such expansive work seem distant, the Post’s past commitment to long-form writing serves it today as a powerful rear engine. For a special edition on baseball, Slon pulled from a profile of Babe Ruth that originally ran at sixty thousand words, spanning multiple issues. For the anniversary of D-d5ay, he used highlights from coverage written by Post reporters embedded with soldiers that day. “It was just spectacular writing,” he says. Therein lies the potential of today’s Post: context, relativity, and practice.

“We give perspective,” Slon told CJR. “You think the world’s crashing around us? Well, let’s look back at times in the past when this has happened, so you can at least understand it as part of the ebb and flow of history.”

Disclosure: In the 1960s, the author’s father worked as art director of promotions for the Saturday Evening Post.

Amanda Darrach is a contributor to CJR and a visiting scholar at the University of St Andrews School of International Relations. Follow her on Twitter @thedarrach.