On the afternoon of April 25, 1964, the headline on the front page of the Chicago Daily News blared: “109 Arrested in Vice Den.” The den in question was Louie’s Fun Lounge, a gay club on the desolate outskirts of O’Hare International Airport. Raids of gay bars weren’t uncommon, but the size of this one—and the fact that eight teachers and four municipal employees were among those rounded up—made it notable. The Daily News referred to Louie’s as a “deviate hangout” and included photos of panicked men shielding their faces from the camera. Attempts at anonymity were moot. The paper published the names, ages, addresses, and occupations of several of those arrested.

As Timothy Stewart-Winter recounts in his book Queer Clout: Chicago and the Rise of Gay Politics, the gay Los Angeles magazine ONE decried the article’s “conviction by publicity”—in the years before Stonewall, such public outings were characteristic of how mainstream newspapers reported on homosexuality. The gay press, insofar as it existed, operated essentially underground, hampered by homophobic printers and Comstock laws that, until 1958, prohibited mailing “obscene” material. The major gay publications of the 1950s and early ’60s—ONE, the Mattachine Review, and The Ladder, a lesbian journal—couldn’t compete with the circulations and budgets of the big urban dailies. (At their peak, these three gay publications had between four and five thousand subscribers each, although copies were passed around like holy contraband.) That changed after Stonewall, when the gay press emerged as a vibrant and mobilizing counterweight to mainstream papers, in local influence if not in size. According to Gay Press, Gay Power: The Growth of LGBT Community Newspapers in America, edited by Tracy Baim, more than one hundred fifty gay publications operated throughout the United States by 1972.

One of the most distinctive was Fag Rag, founded in Boston in 1971. It was the brainchild of Charles Shively, a history professor, poet, unconventional scholar of Walt Whitman, anarchist, and incendiary theorist of gay liberation. Although Fag Rag was produced by a revolving collective of volunteers, Shively was the publication’s ideological mainstay. His commitment to sexual freedom was inseparable from his commitments to political, economic, and cultural revolution. In a series of provocative essays—among them, “Indiscriminate Promiscuity as an Act of Revolution,” “Bestiality as an Act of Revolution,” and “Incest as an Act of Revolution”—Shively laid out an idiosyncratic and unabashed vision of queerness as an egalitarian, feminist, anti-capitalist, race-conscious, and defiantly countercultural force. His essays were confessional and adventurous, and drew examples from his own sex life to bolster his structural critiques. That sensibility was in line with the slogan of second-wave feminism, “The personal is political,” and it sustained Fag Rag for thirty issues between 1971 and 1987, years that spanned the ecstatic dawn of gay liberation through the depths of the aids crisis.

At a time when gay liberation was still finding its political footing, and still honing the movement’s priorities and rhetoric, Fag Rag presented queerness as a repudiation of everything wrong with America.

It all began in November of 1970, when the Boston chapter of the Gay Liberation Front activist group produced a newspaper titled Lavender Vision. After just two issues, most of the gay men on staff decamped to San Francisco, leaving the women to convert the paper into a lesbian-only outlet. The gay men still in Boston, led by Shively, launched their own periodical called Fag Rag.

The new publication was part of a burgeoning wave of gay and lesbian magazines and newspapers that included Come Out! in New York; Gay Liberator in Detroit; Gay Sunshine in Berkeley/San Francisco; Dykes & Gorgons in Berkeley; Amazon Quarterly in Oakland; The Furies in Washington, DC; and many others. Although each had a unique style, nearly all of them shared “a brisk brew of sexual liberation, anarchism, hippie love, drugs, peace, Maoism, Marxism, rock-and-roll, folk song, cultural separatism, feminism, effeminism, tofu/brown rice, communal living, urban junkie, rural purism, nudism, leather, high camp drag, gender fuck drag, poetry, essays, pictures, and much more,” as Shively recalled in a later essay.

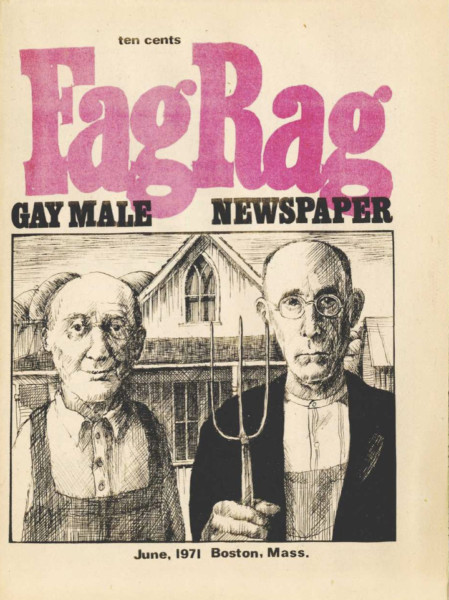

Fag Rag issue 1, 1971

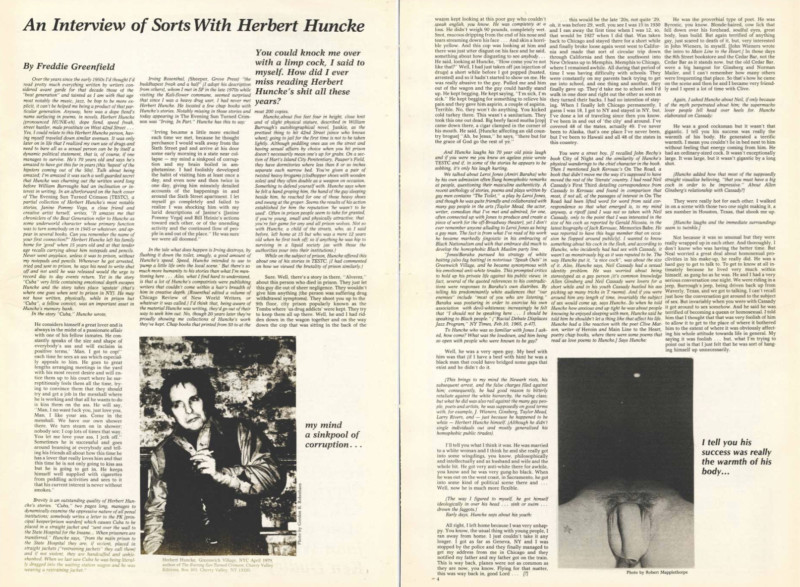

Still, the sensibility of Fag Rag was unmistakable. It was irreverent, as its brash name and deliberately unpolished aesthetic attested. The cover of the first issue was a spoof on Grant Wood’s American Gothic, with two stodgy gay men posed in front of the farmhouse. The paper’s sympathies lay with those who were politically or economically oppressed. Many issues featured letters from incarcerated men, as well as articles by them, and free copies were distributed to prisons. Each issue was also erudite and literary, as was to be expected from a collective that included Shively, the poet John Wieners, and the writer John Mitzel, who at the time sold tickets at a gay porn theater. The paper’s editorial policy was to publish two poems from anyone who submitted, no matter the quality (nearly seventy poets submitted to each issue). Contributors and interviewees included figures now renowned in gay literature, including Gary Indiana, Dennis Cooper, Christopher Isherwood, Herbert Huncke, and Gore Vidal.

Fag Rag reported on subjects few other publications then covered: gay soldiers in Vietnam, gay life in Cuba, gays and aging, gays and welfare, gays with disabilities, gay sex workers, interracial gay relationships. More controversially, the paper later supported what it characterized as adolescents’ right to sexual freedom, as well as consensual sex between adults and children—stances that alienated some readers. Tom Reeves, who spearheaded such content, helped found the North American Man/Boy Love Association (nambla), ultimately one of the most reviled gay male advocacy groups in the country, although it had mainstream support by Allen Ginsberg and longtime activist Harry Hay, as well as some prominent feminists. nambla’s mission, worked out in the pages of Fag Rag, was partly a backlash against Anita Bryant’s “Save the Children” campaign of 1977, during which police raided a house in suburban Boston and arrested twenty-four men who reportedly operated a sex ring of underage boys.

Shively laid out an idiosyncratic and unabashed vision of queerness as an egalitarian, feminist, anti-capitalist, race-conscious, and defiantly countercultural force.

The paper’s volunteer staff met in the basement of Cambridge’s radical Red Book Store (named in homage to Mao). Editorial decisions were made collectively. As a note in the paper explained: “Our general editorial policy is not to publish racist, sexist, ruling class, patriarchal, anti-feminist or other offensive material. (The FBI and CIA already own many outlets for such work.) Specifically we avoid writings which show reverence toward ‘god,’ ‘family,’ ‘state’ or other oppressive institutions. And we avoid printing words used to belittle those in the struggle.”

The writer and later Harvard professor Michael Bronski, who began working on Fag Rag in 1972, remembers those committee meetings as “fun and gossipy and campy and cruisy…a combination of work party and consciousness-raising group.” Issues appeared off-schedule, despite the paper’s intention to be a quarterly. “We are faggots with a lot else to do,” explained a note in the third issue, from 1973. “Making love, learning to love one another, our selves, our bodies, and making revolution.”

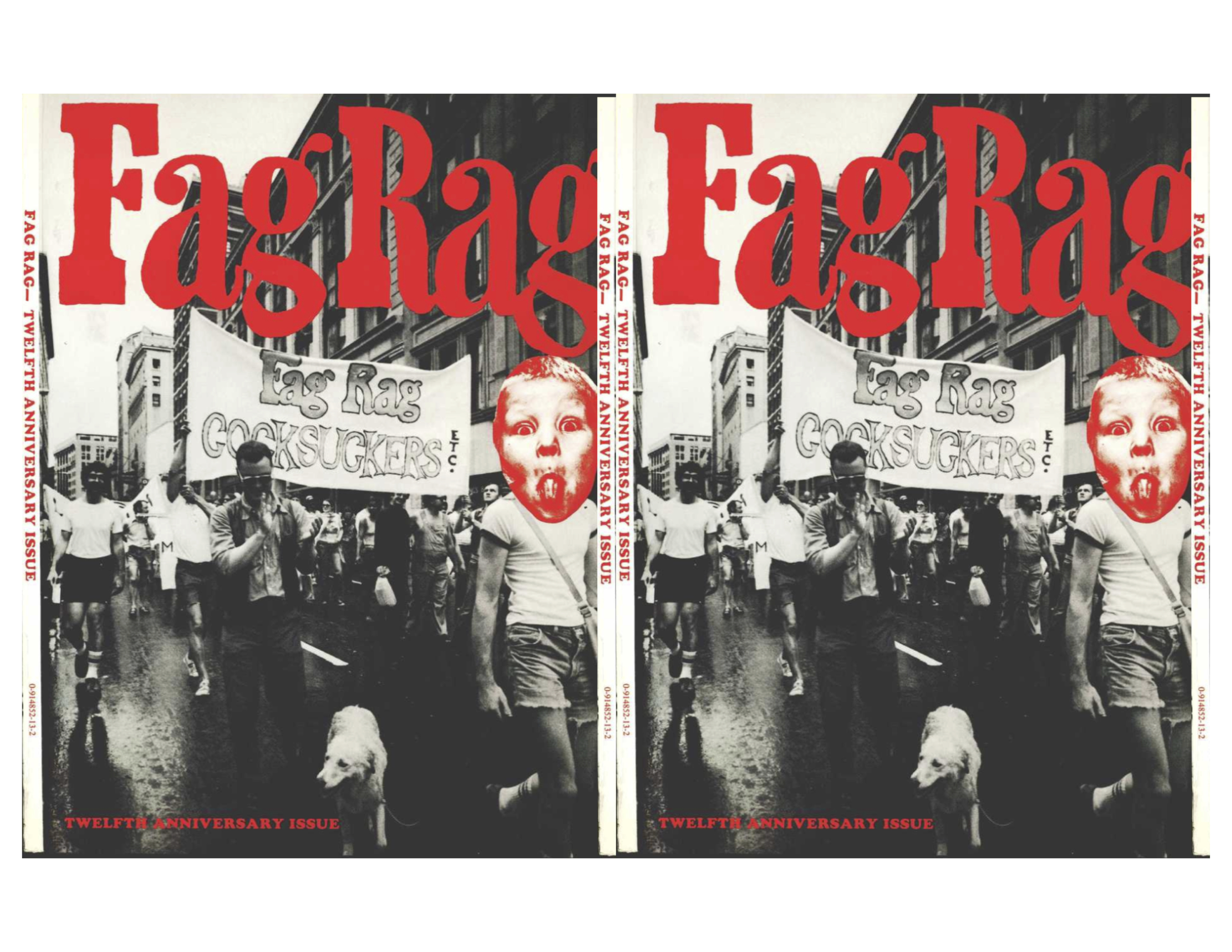

Fag Rag issue 29

Once an issue was printed, Shively loaded his blue VW Bug with copies and distributed them by hand throughout New England. Other copies were mailed to gay and alternative bookstores across the country, sold singly at political rallies, gay pride events, and on the street in Harvard Square, or via $100 lifetime subscriptions. (Fag Rag’s cover price went from a dime in the early days to one dollar by the mid-seventies to $3.99 by the time the final issue rolled out.) Bronski estimates that early issues had a print run of two thousand copies, which cost around $500 to produce. Fag Rag didn’t accept advertising (ads are “bribery and ugly,” a note in the paper proclaimed), so the publication was funded by sales, donations, and occasional government grants. “Those first eight to ten issues were revelations to many readers,” Bronski says. Judging by the letters to the editor, those readers ran the gamut from incarcerated people to farmers to barstool theorists of gay liberation, and occasionally included women.

PREVIOUSLY: It wasn’t easy to describe The Outline. That’s what made it great.

At a time when gay liberation was still finding its political footing, and still honing the movement’s priorities and rhetoric, Fag Rag presented queerness as a repudiation of everything wrong with America (while still acknowledging the flaws of gay liberation). As an editorial from 1973 notes, “Because the order of the world starts and ends in the family with Daddy, fascism comes not only from the nuclear family but from compulsive heterosexuality.” For Shively and his cohort, queerness was as much a moral as a sexual orientation; it subverted the “natural” order on which capitalism depends, opening new possibilities for social and ideological communalism. In 1972, the collective codified its political objectives when Shively and a few associates drove to Miami to deliver a list of ten demands to the Democratic National Convention. Among their requests:

- An end to discrimination based on biology; no government agency should record age, skin color, or gender

- An end to discrimination based on sexual preference

- An end to the traditional family, which should be replaced by cooperative parenting

- A guaranteed annual income for all Americans; the wealth of straight white men should be redistributed

- The disbanding of all armed forces and uniformed police, including the FBI, CIA, IRS, and narcotics squads

- The legalization of sex between all consenting individuals

- Self-government and self-determination of all people

Although the demands were too outré for the platform of any major political party in the early 1970s, they nonetheless demonstrate how prescient Fag Rag was in centering racial equity, anti-policing, and a universal basic income within a larger socialist framework. Shively further linked these ideas to sexual liberation. In his 1972 essay “Cocksucking as an Act of Revolution,” he argued that gay men internalize the bodily shame and squeamishness of their straight bourgeois counterparts. “The male identification with the hierarchical and power tripping world destroys love itself; the sensual and pleasureful tends to be forgotten,” he wrote. “Sex, sensuality, our bodies, and their parts should all feel wonderful and beautiful.” In a sidebar, he suggested practical ways to overcome entrenched self-hatred: home nudism, uninhibited masturbation, and open bathrooms.

Fag Rag issue 42–43, 1986

Not everyone was enamored of Fag Rag’s frankness. Several presses refused to print the paper. According to Shively, one printer told him it couldn’t roll out Fag Rag on the same machine used to print Bibles. In Atlanta, a bookstore declined to carry the paper because it contained images of Black men. In 1973, Shively distributed Fag Rag at a play on the campus of the University of New Hampshire. He claimed that “police spies” delivered copies to the governor, the state attorney general, and local media. A firestorm ensued, in which Fag Rag earned the irresistible sobriquet of “one of the most loathsome publications in the English language.”

By the 1980s, there were more than 700 gay publications in the United States. Contrast that with today, when fewer than 20 local gay newspapers exist.

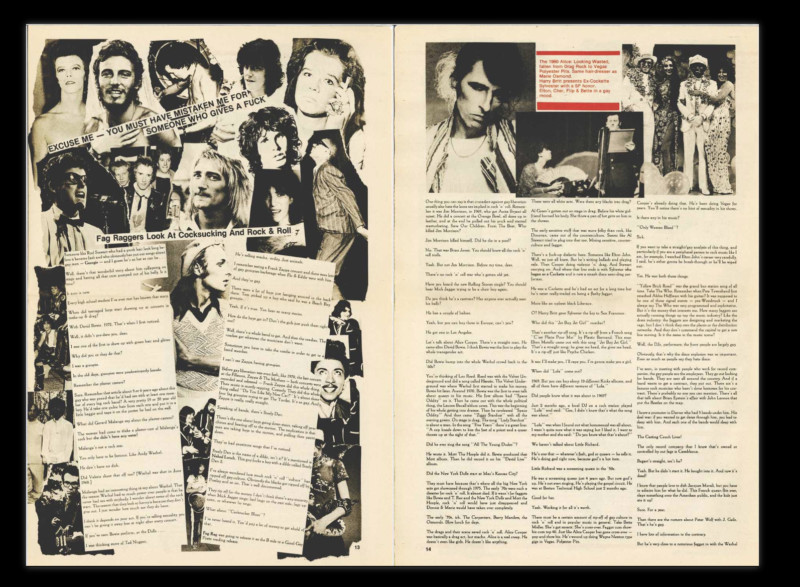

Fag Rag maintained its ragtag charm even as the staff changed from one issue to the next. Articles mixed personal essays with manifestos, humor with outrage. A brief index of subjects evokes the paper’s range: J. Edgar Hoover, rural queers, group sex, sadomasochism, Cabaret, the literary critic F.O. Matthiessen, West Germany, masturbation, W.H. Auden, the Kennedy assassination, the Russian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov, the Seabrook nuclear protests, etc. In 1974, early installments of Arthur Evans’s Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture appeared; these were collected and published as a book in 1978, under the imprimatur of Fag Rag Books. It may have inspired a letter to the editor that read: “Each time I read the RAG I get the feeling—and this is meant to be unmitigated criticism, in case you didn’t think so—that the paper comes out of California. Witchcraft. Bestiality. Far out. Very in.”

Every issue also contained delicate erotic drawings to accompany the poetry. Black-and-white portraits of beautiful men and boys (sometimes naked) punctuated the text. The Fag Rag collective didn’t believe in copyrights, so photos by Robert Mapplethorpe, for example, appeared along with the work of local amateurs, everything juxtaposed with the same nonhierarchical spirit that informed the paper’s editorial credo. Sardonic humor predominated, as in the satirical “Lord Baby Jesus Christian Gift Catalogue,” which appeared in the winter 1974 issue. Among the mock gifts listed was “Crippling Christian Guilt: Long wearing, permanent press means just one gift of Lord Baby Jesus guilt can last a lifetime when administered properly.”

Much of that humor soured as hiv/aids ravaged the gay community in the early 1980s. A subset of the Fag Rag collective was critical of public health officials, policymakers, and some gay HIV activists who called for restrictive safe-sex measures and monogamy. From today’s vantage, the tone feels out of sync with the tragic reality on the ground, but anything that threatened the hard-won prerogatives of gay liberation was verboten. In an issue from 1983, Shively asked readers: “Are you willing to die for sexual liberation?” He then touted a then-popular conspiracy theory that the CIA introduced the virus to the Western Hemisphere. Shively “lost his audience by the time he wrote the aids piece,” Bronski says. In 1994, Shively was diagnosed with HIV himself, although he told almost no one—a rare instance of reticence from a man who made a career of self-disclosure.

Fag Rag issue 44

By the 1980s, there were more than seven hundred gay publications in the United States, everything from glossy newsmagazines such as The Advocate to local weeklies, bar guides, neighborhood newsletters, and zines. Contrast that with today, when fewer than twenty local gay newspapers exist and legacy publications such as Out and The Advocate have been downsized after losing their high-profile editors. Online LGBTQ publications haven’t fared much better. Into, the much-hyped digital magazine published by the social networking app Grindr, shut down in 2019 after a year and a half. Them, published by Condé Nast, still exists, albeit without its founding editors. More artsy gay publications such as Butt and Hello Mr. ceased publication as well. Pinko, a semiannual print journal of “gay communism,” debuted last year after a successful Kickstarter campaign, and is in some ways reminiscent of Fag Rag’s collective spirit.

That Fag Rag survived almost two decades and multiple mastheads is a testament to Shively’s vision, but also to the conviction of its staff and the devotion of its readers. Bronski recalls that gay men across the country sent letters and artwork to the editors, often noting it wasn’t safe for them to keep such material in their homes, where bigoted family members might find it. Shively saved all of this correspondence—plus subscriber records, essay drafts, invoices, and receipts, a whole clandestine archive—until he died, in 2017.

Fag Rag wasn’t an idealistic publication; it didn’t suggest that a gay utopia was possible or even desirable. Instead, it pushed for a political revolution that wouldn’t come at the expense of other marginalized groups. The paper’s provocative wit now seems like a precursor to the guerrilla actions of act up. As Shively wrote in 1978, “What all peoples in struggle need is a picture more of resistance than of how wounded we are.”

“Fag Rag kept true to its core vision of that original anarchist, in-your-face sensibility,” Bronski says. “It shook the cultural, social, and political senses without ever doing it solely for that reason. It didn’t shock just to shock.”

It shocked for the sheer joy, the sheer rage, of it.

Author’s Note: Special thanks to Michael Bronski for his extraordinary generosity during the research and writing of this essay.

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The Nation, Art in America, the New York Review of Books, and elsewhere.