Corporate media is suffering. Risk-taking is a notion from another era, before financial constraint and hostile politics. But in independent publishing, things still happen organically. From a porch in San Antonio, a dorm room in upstate New York, or a library in Chicago, the makers of indie magazines say that their beautiful, surprising, original projects came about as a natural culmination of years of experimental art or writing for an audience of one.

It’s no utopia: very few people get rich making indie publications. But there is freedom. “We made up our own rules for ourselves,” Isabel Ann Castro, a founder of St. Sucia, which she describes as “a zine where brown girls just talk shit and be very real,” said. “Because Coca-Cola wasn’t sponsoring it, there was no one to pull advertising because of abortion stories.”

As we focus on the layoffs, the bankruptcies, the journalists jailed for doing their jobs, it’s worth remembering that there’s one form of journalism that can never really be killed—someone who has something to say, and says it without asking permission.

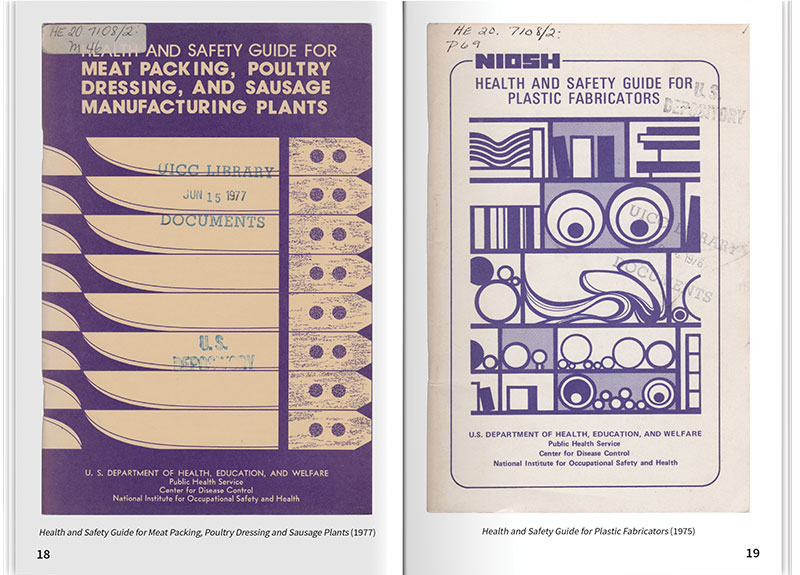

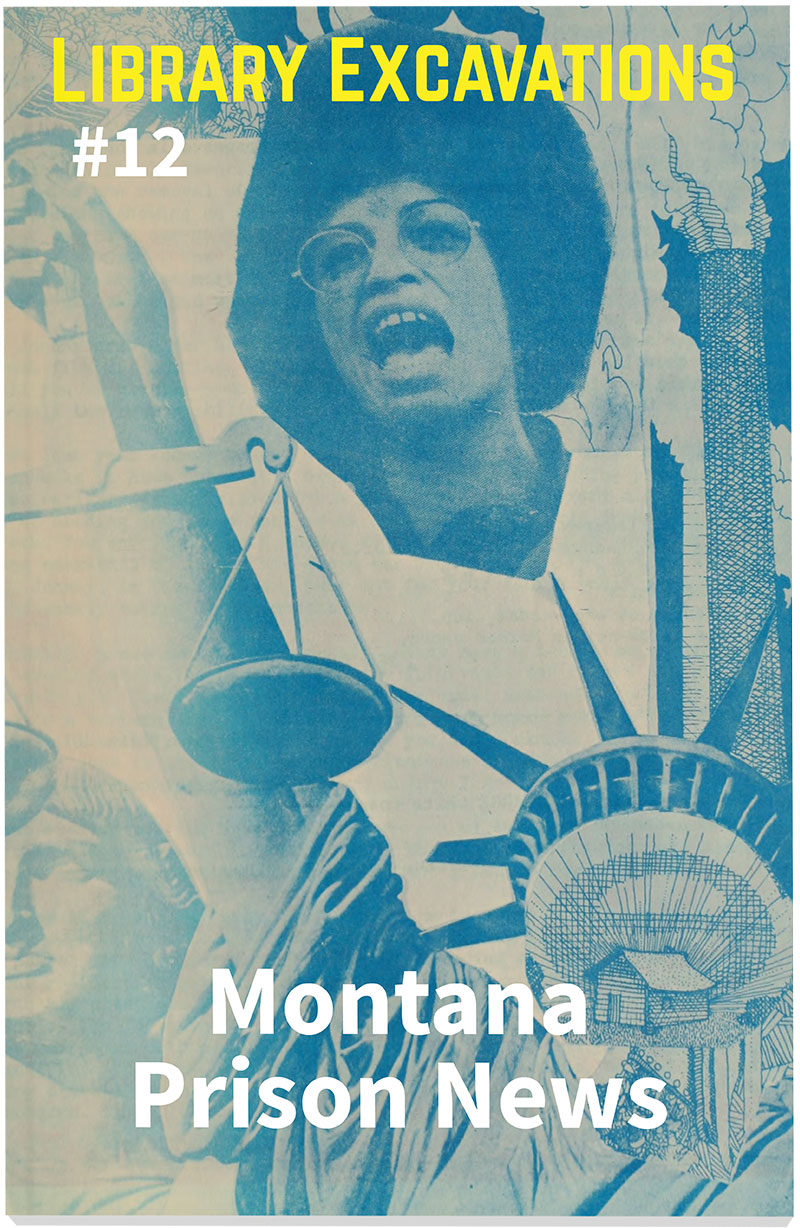

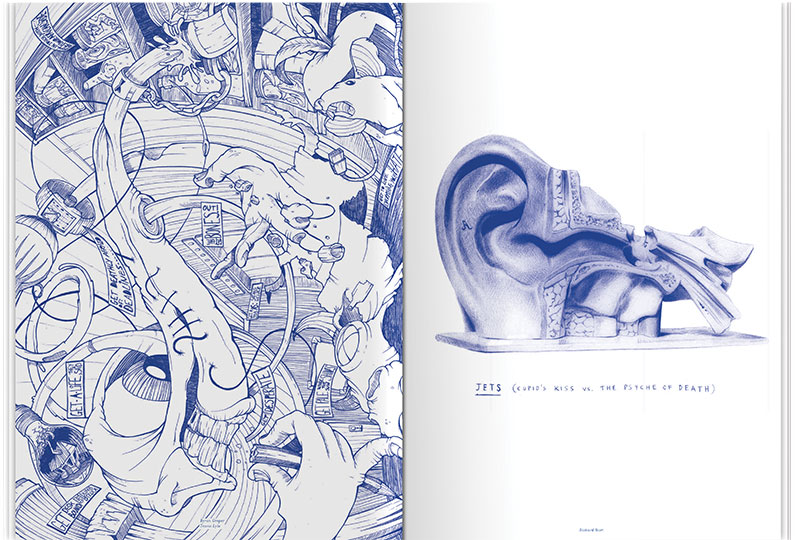

Library Excavations

Public libraries, Marc Fischer would like readers to know, are not just for books. The “frequently strange and unsettling world of US Department of Defense training photographs” is waiting to be discovered in the National Archives at College Park, in Maryland, much like the 1970s booklets produced by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health sitting at the University of Illinois, and the archives of the Montana Prison News that live in the Montana State Library. “There’s stuff that’s been sitting online for a decade, and maybe thirty people have looked at it,” Fischer, the founder and editor of Library Excavations, said.

Fischer treats libraries “the way that maybe other people would visit a museum or a flea market. Sometimes you’re trying to return to your favorite section, and other times you’re exploring aimlessly.” Excellent graphic design, after all, can be found anywhere, like in a 1978 Volvo car repair manual. “It’s a process of maintaining openness and receptivity.”

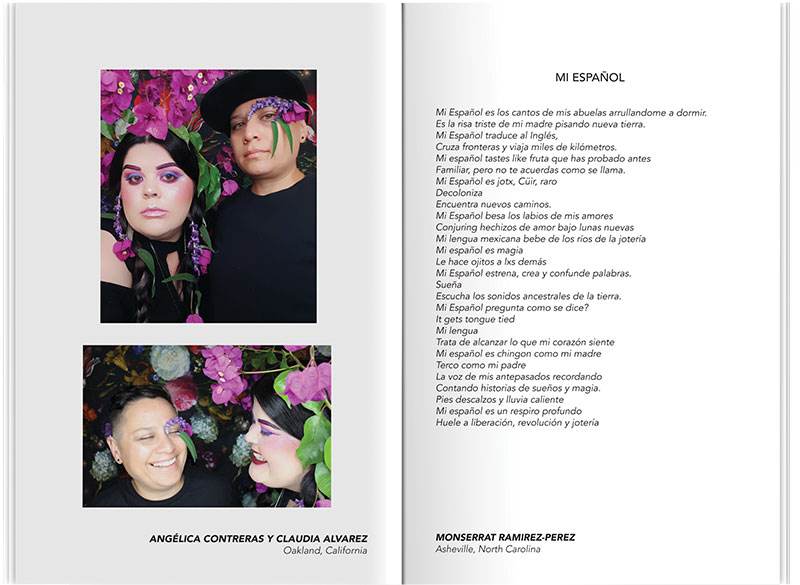

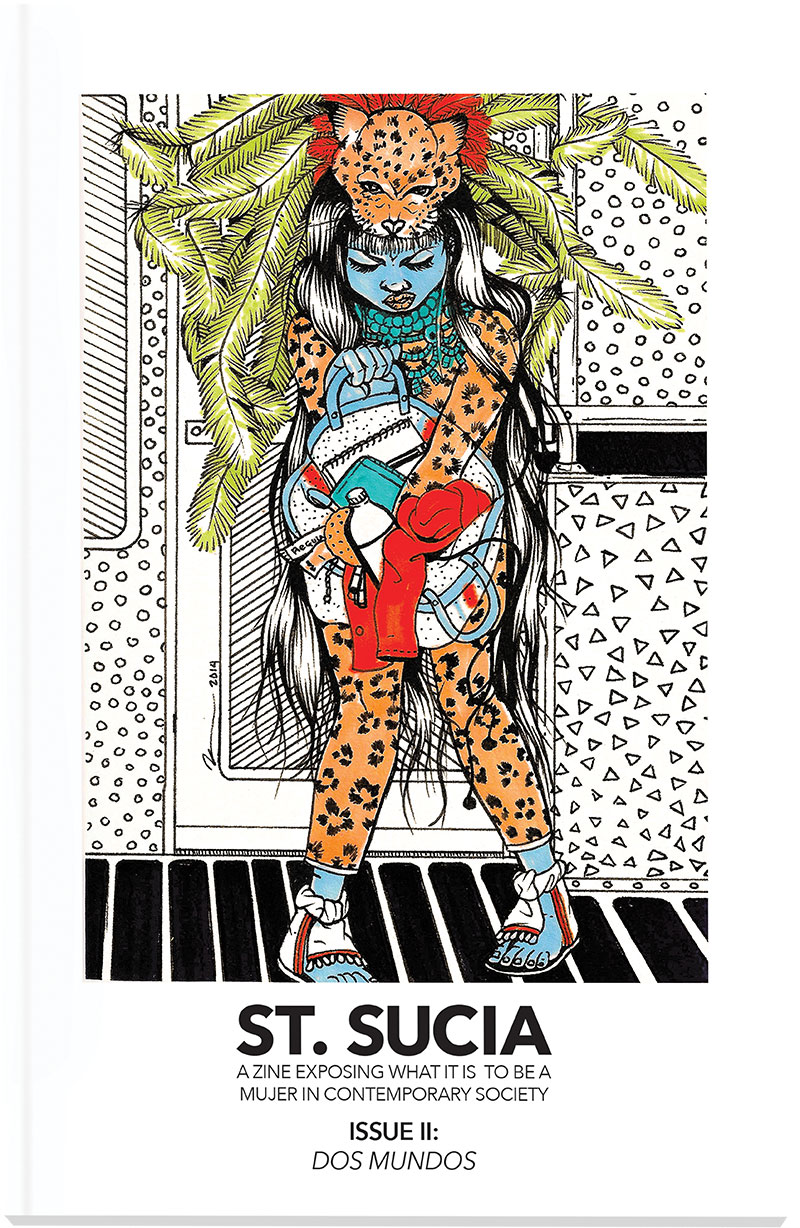

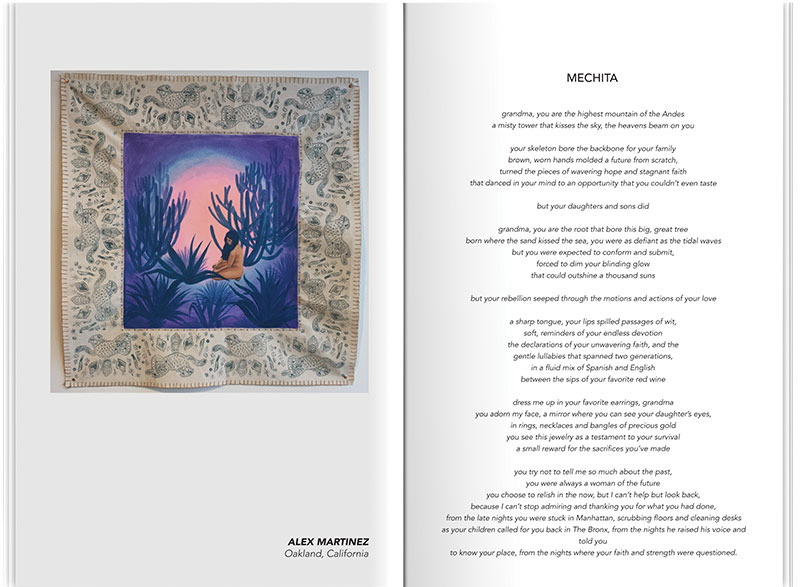

St. Sucia

The idea for St. Sucia began when Isabel Ann Castro was in college and her friends would pray to Catholic saints, asking for a date to go well or for their Plan B pills to work. “You guys can’t be asking Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary for this shit! We need a separate saint, a modern woman who gets it,” Castro would say. “It’s gotta be a dirty girl—a sucia.” Soon, “St. Sucia” became an in-joke.

Castro later spotted Natasha I. Hernandez, an acquaintance, at a bar. “There was music playing really loud, and she was standing by a trash can getting ready to go outside and have a cigarette. And I was yelling in her ear, ‘Do you want to make a zine where brown girls just talk shit and be very real?’ ”

Although the zine was initially filled with short stories, quizzes, listicles, and poems about love and dating, it also covered weighty topics, including reproductive justice, education, gender identity, and immigration, from the start. Late last year, Castro decided the zine had run its course—but the spirit of St. Sucia will live on through new projects, like a screenplay that Castro and Hernandez are working on.

Photograph of Natasha I. Hernandez (left) and Isabel Ann Castro, taken in October in San Antonio by Julysa Sosa

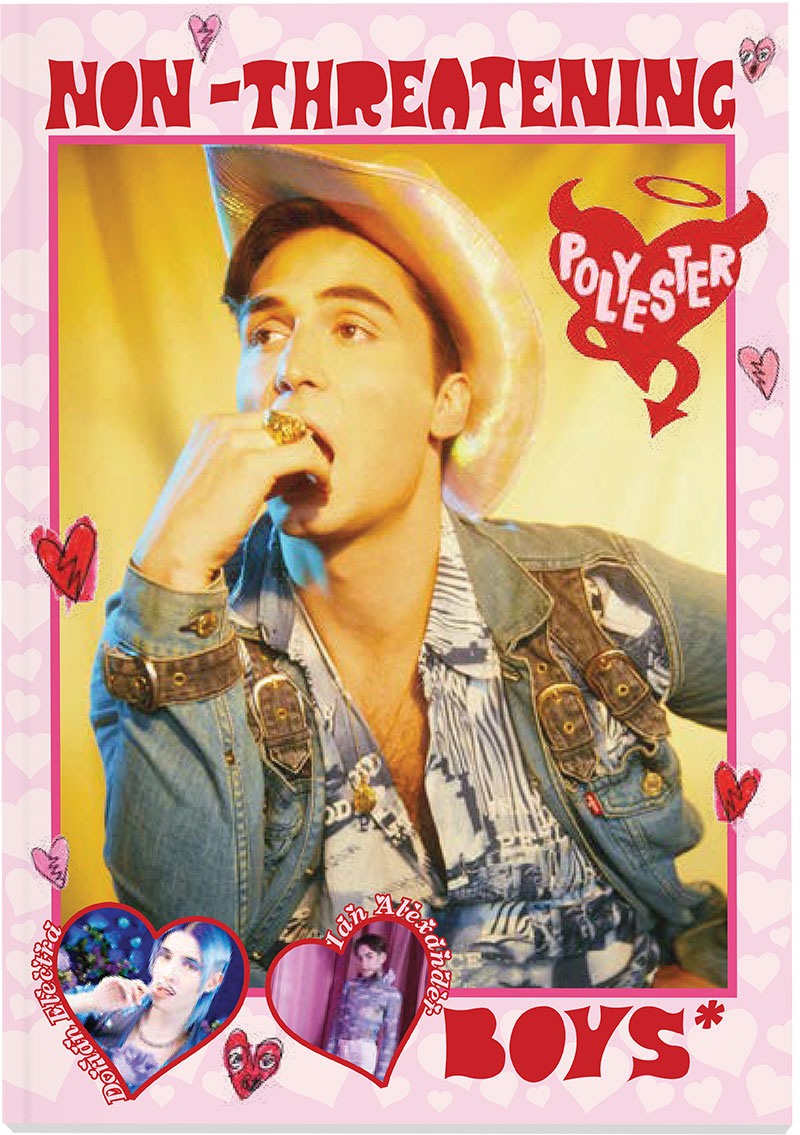

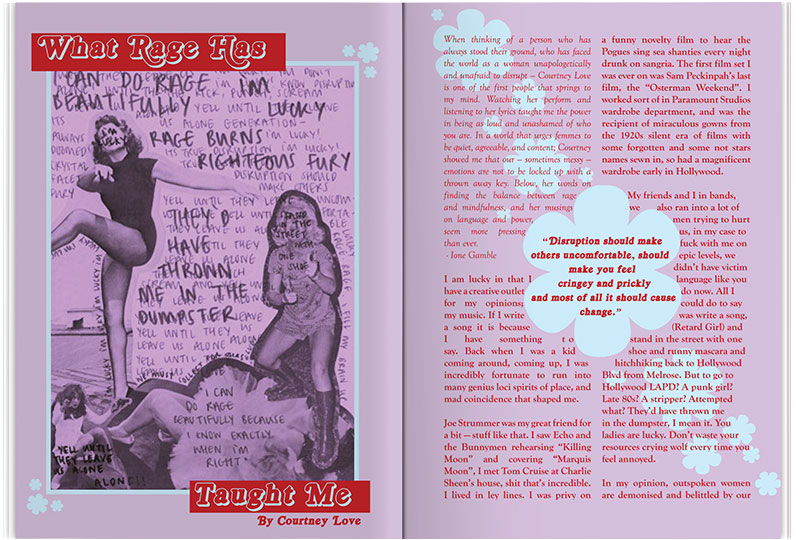

Polyester

Polyester—whose John Waters–inspired tagline is “have faith in your own bad taste”—is gaudy, in the best way. When you read an installment of the newsletter on Polyester’s website, small pink hearts trickle down the screen as you scroll; the black arrow clicker disappears in favor of a red heart with an angel’s halo and devil horns. Polyester takes racism, transphobia, and systemic injustices seriously, but not itself. Here, counterculturalism is supposed to be fun.

Ione Gamble, Polyester’s founder and editor, said she was “obsessed with magazines growing up, so I always saw print as this aspirational goal. I wanted to make something that everyone could be involved with, as opposed to having this higher attitude about it.”

“Just show people something that they will relate to more and feel uncomfortable for the right reasons,” Gamble says. Photograph of Ione Gamble by Jender Anomie, shot in October in Peckham, London.

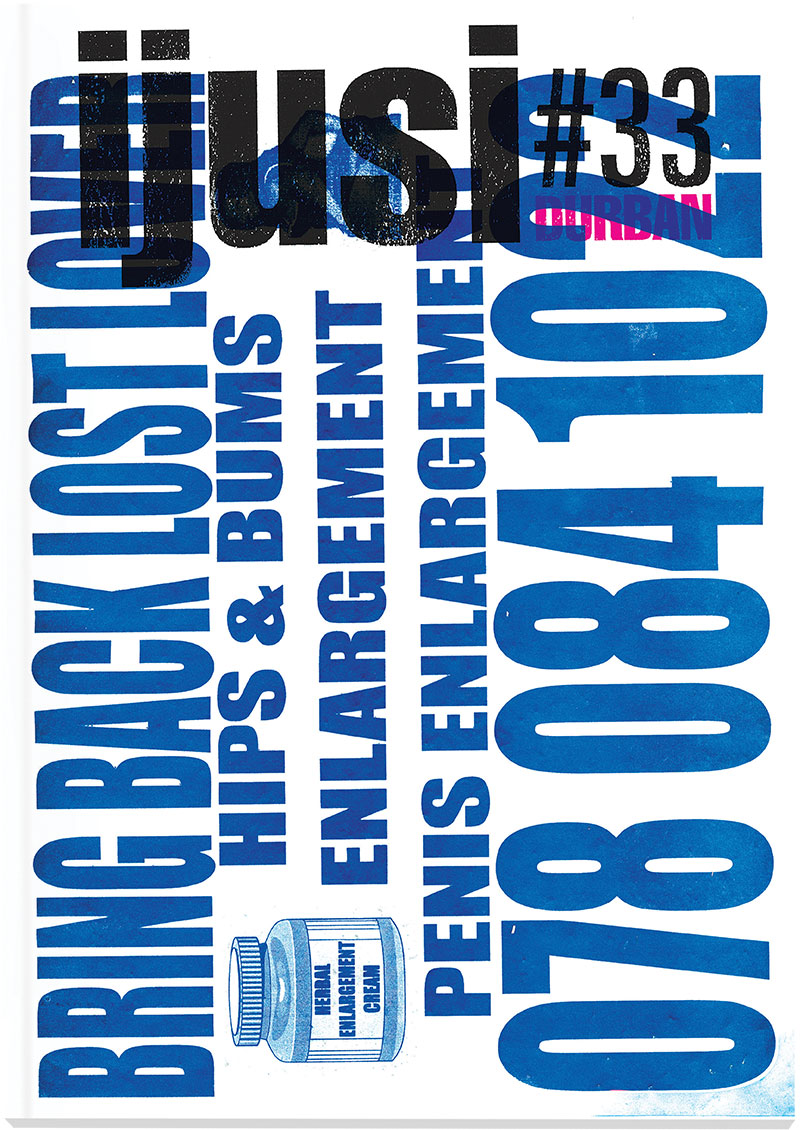

iJusi

If you’re ever in Durban, South Africa, and you spot a man jumping off his bicycle to pry an ordinary-seeming flyer from a lamppost, it’s likely you’ve found Garth Walker. A graphic designer, Walker has been documenting street design in South Africa since the 1980s. “So by 1994,” he said, “I had this large archive of stuff from the streets and townships that I was interested in doing something with, and the easiest way to get this body of work out there was to design a magazine.”

He published the first issue of iJusi in 1995, just after Nelson Mandela had been elected president in the country’s first fully democratic vote; an art scene was reviving postapartheid. Before then, Walker said, the country’s design industry sought to appeal to the white minority. But he wanted to answer the questions—and to provide a platform for South Africans of all backgrounds to consider—“What makes me African, and what does that look like?”

Each issue since then has explored those questions, enlisting contributors who are graphic designers, photographers, or writers. The answers are always changing, Walker said. Now on its thirty-fourth issue, iJusi has delved into topics as diverse as human rights, porn, the legacy of Mandela, and African typography.

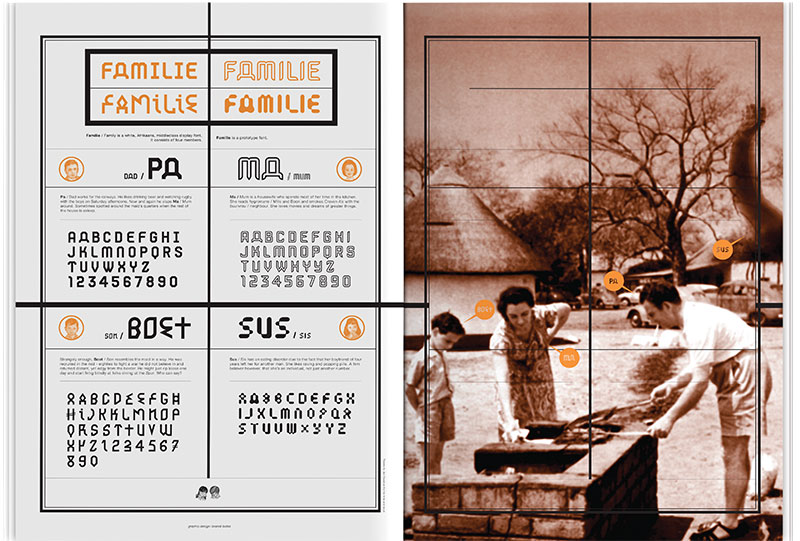

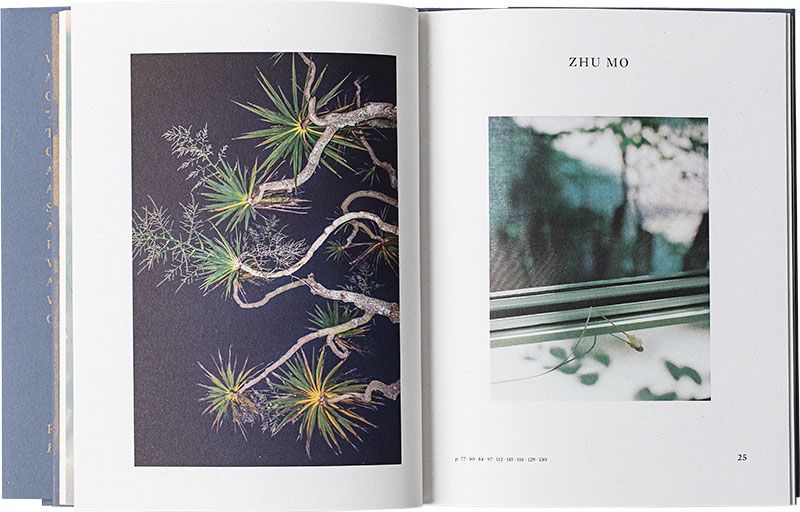

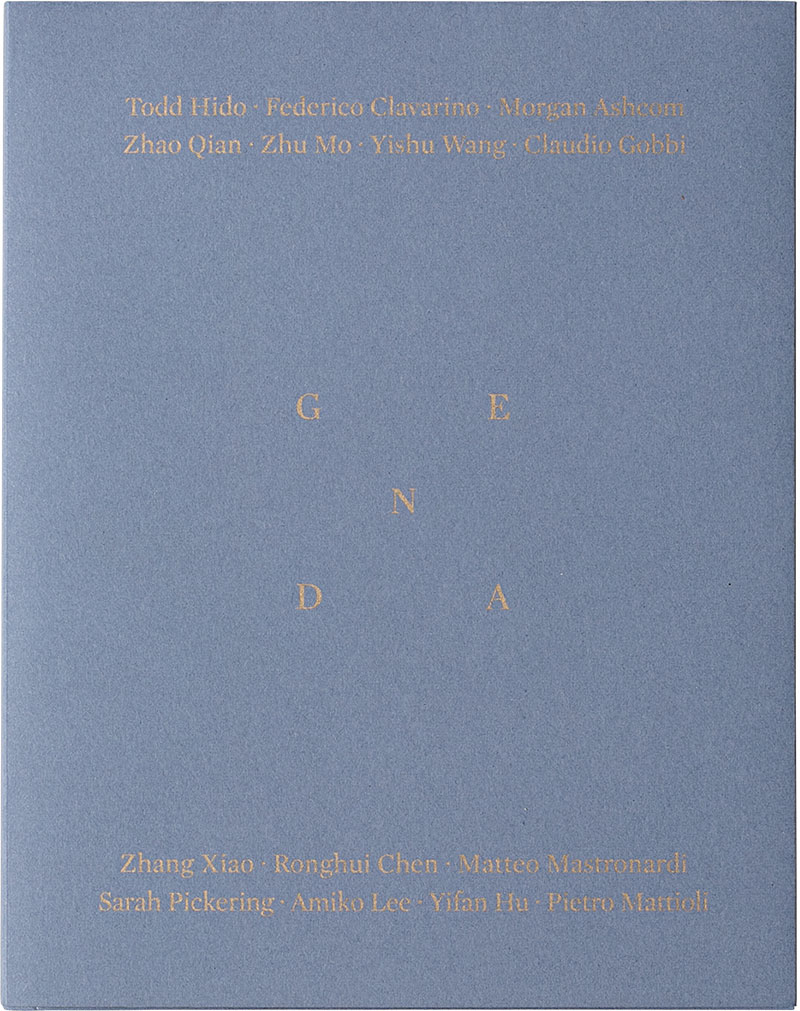

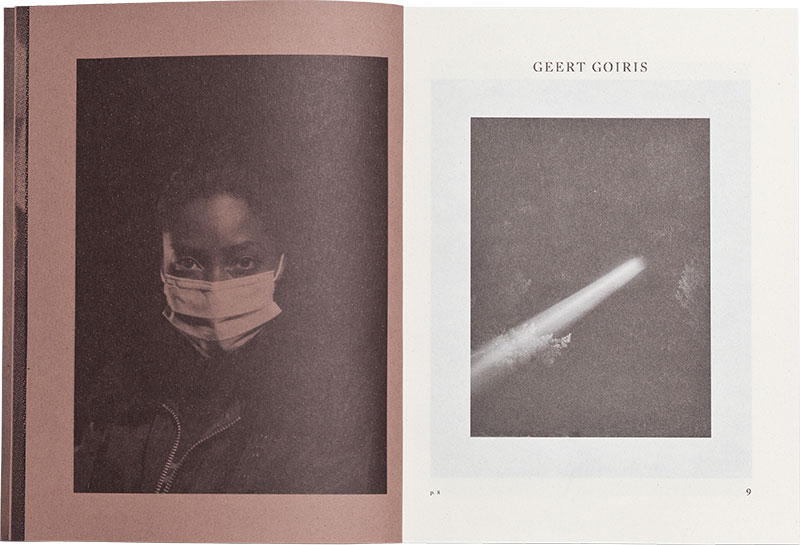

Genda

Of the many traps that the American media set for itself during the Trump presidency, a facile dedication to studying “societal divides” is perhaps the most grating. Genda magazine is an antidote. With a masthead split between China and Italy, and contributors from around the world, Genda devotes each issue to a single, often esoteric, theme—like “landscape as abandon” or “endless scenarios”—and uses photography to examine what its editors call “misunderstandings and complicities at the base of every concrete exchange.”

Genda takes its name from a mistranslation of the Chinese word zhende or zhenda (“really”). “Our hope,” Silvia Ponzoni, one of the editors, said, “is that misunderstanding could be a way to know each other better.”

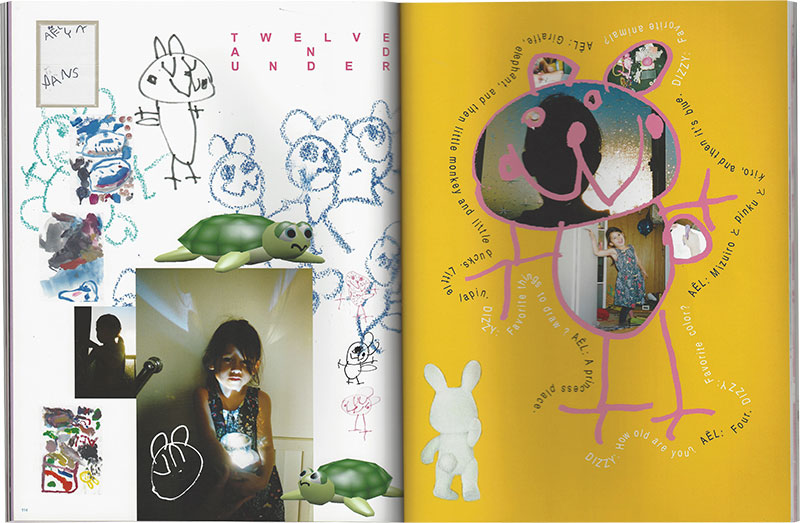

Dizzy

The founders of Dizzy, a pair of artists named Milah Libin and Arvid Logan, value childhood. Dizzy’s homepage greets you with a cartoon of a young girl with blue hair, enlarged eyes, a plaid dress, and enormous sneakers. A turtle is next to her; it does not look happy.

Libin cites Cricket, a literary magazine for children, as an early influence. “It really took children seriously and their work seriously,” she said. “Kid art is the best. I’ve always felt that way. It doesn’t have any of the ego that grows when you enter the art world. It’s not even a choice—it just happens.”

The resulting independent art magazine has been cited in the New York Times and called, by ARTnews, “Something that makes you remember what you loved about magazines in the first place.”

Savannah Jacobson is a contributor to CJR.