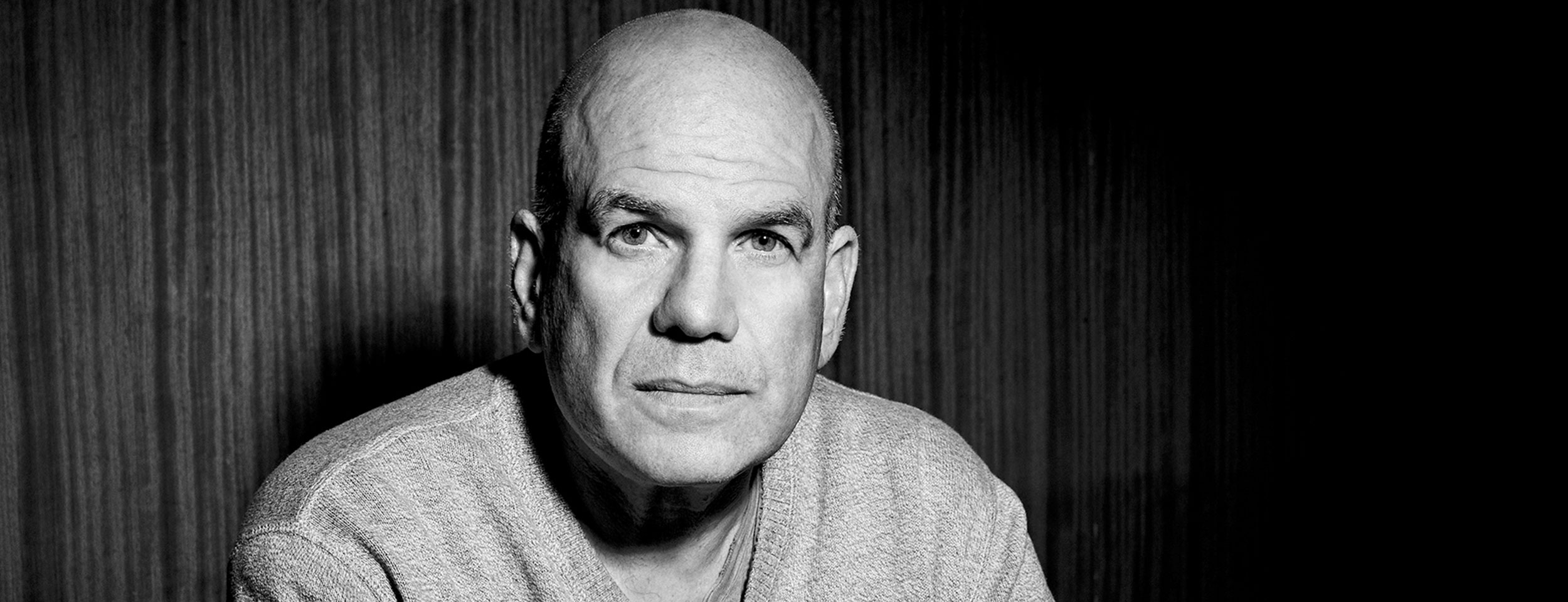

David Simon has produced some of TV’s most groundbreaking series. But he has never forgotten that he started as a journalist, with more than a dozen years spent as a reporter at The Baltimore Sun, mostly on the cops beat.

His first book, Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets (1991), became an NBC series, and his second—written with Edward Burns, a homicide detective in Baltimore—The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood (1997), was made into an HBO miniseries. By 2002, he had created a series for HBO about the war on drugs in Baltimore hailed as one of the best dramas in the history of television: The Wire.

Still, Simon always thought he’d be back in newspapers before long. “The whole time I was doing The Wire, I thought ‘When this is done, I’m gonna go to The Washington Post,” he says, referring to a standing job offer there.

From archives: What The Wire reveals about urban journalism

For him, The Wire’s story was “journalistic,” making the argument, rooted in real experiences, that the “War on Drugs” was ineffective and had become a war on America’s underclass.

The Wire fleshed out characters often left out of narratives elsewhere—especially in Baltimore’s poor, black neighborhoods—humanizing people in marginalized places. President Barack Obama namechecked it as his favorite show.

So what can a white recovering journalist from Montgomery County, Maryland, tell today’s reporters about how to cover people of color and underserved communities? In a recent conversation, edited substantially for length and clarity, Simon, 58, offered some answers.

SIMON: I had a different advantage than many other people working in television. They made me a police reporter for a metropolitan daily in a majority-black city. So there was a fundamental sort of fork in the road for me. Either I’m going to become one of those police reporters who is wholly dependent on the police department for information, or I’m going to learn how to listen to people in cadences other than my own. It wasn’t just about race, it was also about class and it was about ethnicity. I can’t remember hearing the “n” word once in my entire time growing up. That’s a pretty sheltered life in America; I didn’t even hear it thrown around by white people. When I came to Baltimore, 30 miles north, I heard race discussed and invoked in ways that I never had growing up. By the time I hit the ground writing scripts, I wasn’t trying to write black or white or Irish or Italian cop or noncop. I was writing people I knew. I was really trying to stream actual voices and stories that I had come to know over those years into script form. And that made it a lot easier than sort of sitting back and going, ‘Oh it’s time to write a black narcotics detective. I wonder what he would sound like?’ I’m just writing people I know.

DEGGANS: Sounds like part of your success, which journalists can emulate, is taking time to get to know a beat and the people who are part of that beat.

SIMON: This is really hard, now that journalism is so thinned out. But one of the great things that happened to me is I never got promoted. I just kept finding more and more resonance in what I was covering, and I got better at it. One of the things that happens nowadays in journalism is—you did good at being the police reporter, it’s been eight months, you’re now covering the election. You know that’s a recipe for the Peter Principle. But it’s also a recipe for never getting below the surface. The Wire is the work of somebody who went through a 15-year period of buying into the system, then evaluating the system over time, and then critiquing the system.

If I wanted to hear anything from anyone other than the police, I had to be able to walk into a rowhouse and convince people very quickly that I’m not a cop and I really want to hear what you have to tell me about what happened last night. And there were reporters who did not want to open that door.

SIMON: This is a little bit hard; to critique my own hiring by The Baltimore Sun. When I got to the Sun, there were four police reporters. One of them was African-American. It was a city that was (nearly) 60 percent black at that point. Maybe putting me on the police beat was a little bit of an affront. A paper that was more racially sensitive, that was thinking ahead, even in 1982 or 1983 (might have done things differently). The way they looked at it, the police beat was where we put all entry-level people and you’re an entry-level person. They figured they’d move me off pretty quickly if I did okay. But I ended up staying there. Is it a healthy and viable thing for most newspapers to not make a pluralistic newsroom a priority? I don’t think so.

One of the things Baltimore taught me, and I made sure to teach it to my kids: if I’m going to do this beat right, I have to walk into places and be the only white face or one of two or three white faces in a room full of people who are not white. Is it going to bother you to the point where you’re not going to be able to do your job? Even among white folk who are well-meaning and intent on making human connection, some get scared when suddenly they’re cast into the place they’ve never been before in their life—which is as a minority. I had to get to the point where this not only doesn’t bother me but it doesn’t affect me in any way. This is my day-to-day. And it wasn’t about race, it was about levels of poverty. That did not come naturally. It came by force of the beat itself; the beat demanded that. If I wanted to hear anything from anyone other than the police, I had to be able to walk into a rowhouse and convince people very quickly that I’m not a cop and I really want to hear what you have to tell me about what happened last night. And there were reporters who did not want to open that door.

DEGGANS: But when it comes to a lack of diversity, couldn’t people say that about The Wire? Other than a few scripts from your friend, the African-American writer David Mills, you didn’t have black writers, did you?

SIMON: I asked David Mills to be a writer every single season of The Wire. And he did write two or three scripts for us. But the great ambition of David Mills was to get a network show. I tried out some other people—the truth was Ed Burns and I were writing the drug war of Baltimore. He had policed it; I had covered it. We felt like we had it structurally—we understood what the story was from beginning to end. We attempted to hire novelists (note: authors such as Dennis Lehane, Richard Price, and George Pelecanos filled out the writing staff); we felt like we were doing something new with structure so I tended to not want to hire anybody in TV. I thought about going out to a couple of black novelists and I sort of explored that with agents and found that they had their own stuff that they were trying to develop. Not surprising.

SIMON: We’ve created an American economy that doesn’t actually need its underclass. And Baltimore is a prime example of that. If that’s the case, it is infinitely easier for the drug trade—which is a factory that’s operating 24/7 and is hiring every goddamn day—to acquire adolescent and adult black males. And so what happens a lot in the entertainment industry or in the journalism pipeline is people are running scared. They’re writing tight. It’s from a liberal logic: I don’t want to add to this stigma. So I’m going to actually avoid looking at the entire problem. I didn’t make the drug dealers on The Wire black because I was saying something racial. I made them that way because the drug trade in Baltimore, on that level, was predominantly situated in African-American communities. I was chasing the real. If they only represent a cohort to you, if you’re inclined to a fundamental racism, you see every 14-year-old drug dealer as only a drug dealer. If you’re inclined to liberal apologia, then they’re always going to be victims without agency. They’re never going to be that person who—yes, they were profoundly marginalized by class and by race—and yet there were fundamental choices they made, too.

DEGGANS: Your earlier point reminds me of a speech that Major Howard “Bunny” Colvin makes in The Wire to a young sergeant, saying cops have gotten disconnected from neighborhoods in the war on drugs, because in war, everyone on every corner is your enemy. Have journalists gotten disconnected, too?

SIMON: I greatly resented—really resented—whenever a reporter, and it was invariably white, would make a big deal about how they had taken on some level of imagined or real personal risk in reporting a story in Baltimore. They wanted a pat on the back or extra valuation in the newsroom for having gone to a world other than their own in their imagination and brought back some narrative. It was, like, Fuck you, what do you think, you went to Beirut? You’re supposed to be saying this is part of your city. People live here. They’re completely capable of being as innately human and nuanced as people living anywhere else. And I’m capable of capturing them because I’m a reporter in this city. It should go unstated that nobody gets extra points for getting out of their car. That notion of, My God, this is a dangerous and foreign land is as cynical and calculated and cowardly as a journalist can manage.

DEGGANS: Is it fair to say The Wire was more about class than it was about race, anyway?

SIMON: I think so. We were talking about the people who got left behind at the turn of the century by the American economy and by American society. And so I think being poor in America and being born into poverty, white or black, and being marginalized economically, does have a pathology. It is compounding and it’s generational. And the underclass, white or black, exhibits pathologies that are profound. But I don’t see it as a construct of race, and honestly, I assumed everybody else knew that. The fact is, there are two Americas, and The Wire was about one America and not the other. I used to say all the time as a quote: “Look, there are, let’s say, 479 dramas about one America. For a brief, five season period, we did a drama about the other America that got left behind.” We’re never going to attend to it, ever, if you make it invisible.

DEGGANS: Do news outlets get so caught up in reaching advertisers and subscribers that they turn away from important stories?

SIMON: You ever heard the story that ended me at The Baltimore Sun? When I knew it was time to go? There was a buyout on the table. I’d come back to the paper after researching The Corner. I had an offer from The Washington Post, I also was being offered jobs on NYPD Blue, and I was offered a job on Homicide. But I still wanted to stay at The Baltimore Sun. I grew up there; I have the home phone numbers of 600 cops. But my stories had become much more narrative, and I’m much less interested in reporting what you, the white reader with two point three kids, wants. There’s this whole untapped world of narrative and humanity and emotion that I just want to pull through the keyhole because it’s really interesting.

So I had this one story—the cannibalization of bulk metal. Guys, virtually all of them drug-addicted, were lugging radiators to the scales at scrap yards, to sell the metal. If you don’t think being a drug addict is the hardest job in America, just watch that. So I said I want to do a magazine story on these guys. I went around with them and I wrote the piece up. And it went up the editing ladder. It finally hit the top ranks of editors, and they freaked out because these guys were stealing. I said, ‘Of course they’re stealing. That’s in the piece. Can we not walk beside them because they are petty thieves?’ This is addiction. This is desperation. One editor said, ‘I need you not to sympathize with them.’ There’s plenty of room in the piece to say, ‘Yeah, what you’re doing is wrong and you are doing damage.’ It says all that. But what it also says is these guys are funny, human, and desperate. And they have wit. That was the moment when I realized some people are just never going to get it.

Social media is such that a lie can travel a full day’s journey before the truth ever gets its boots on.

DEGGANS: You’ve been a pretty vocal critic of President Trump. What do you see journalists doing right and wrong in covering him?

SIMON: I think the critical mistakes were made at the beginning of his campaign when he was creating viewership, particularly on cable. And when live coverage of his every utterance was a profit center for journalism. He and his ideas received disproportionate coverage. It was a fundamental failure of institutional journalism. I think, in some ways, journalism came out of that election cycle with an existential crisis—that Trump helped them solve. You’re a journalist; now, you wake up every day knowing that a fundamental element of America is entirely dependent on your ability to stand up to this man. There’s been a lot of good journalism about what’s gone wrong and what is dishonorable about this American moment.

On the other hand, I think what’s problematic is that this president has figured out the deconstruction of how information is transmitted in our society. Social media is such that a lie can travel a full day’s journey before the truth ever gets its boots on. And it can be sustained through falsehood and manipulation, so that it almost doesn’t matter what trained and careful journalists say. It’s why I was engaged on Twitter. Opinions are already being formed and shaped long before they can be addressed seriously by journalists.

DEGGANS: You got kicked off Twitter earlier this year. Twice.

SIMON: The reason I got thrown off Twitter, and the reason I regard it as a rigged game, is that the people running that website, they want to wash their hands of the idea that they have to be in some way the evaluators of what is slander and what is not and what is true and what is not. The only intelligent response to much of what occupies Twitter as provocation has to be to call some users out for the elemental inhumanity on display. I was kicked off for telling somebody to die of boils. It’s basically a slightly funnier and more Yiddishkeit way of saying ‘drop dead.’ I told the guy who thought he could say that George Soros had consigned other Jews to the Nazis as a 14-year-old that he should die of boils. And they blocked me. When I got back online, I basically explained to Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s CEO, ‘Jack, if this is your policy, die of boils.’ And for that tweet, he blocked me again. They can solve all this tomorrow, if they just said: no anonymity. Everyone has to post under their own name. You know what that’s called? Letters to the editor. Now it suddenly becomes human; now it starts to reflect actual human beings rather than political provocation and propaganda and agitprop. But they won’t do that; there’s not enough money in that. So if you’re not going to do that, get the fuck out of my way and let me tell this guy who he really is. (Note: Simon has since returned to Twitter.)

DEGGANS: It seems the central component to creating your characters in The Wire was trust; real people in marginalized communities had to open their lives to you and trust you to tell their stories. Journalists these days are also struggling with trust; many people don’t seem to trust them. What’s the secret?

SIMON: You have to come back every day. It doesn’t happen the first day or the second day or the third day. If you demonstrate that you went and talked to somebody they said you should talk to, if you never lie about what your intentions are, you stand a much better chance of shaving away the distrust until you get down to a veneer of cooperation. And then if you keep going, eventually, you might get to the area of actual trust.

There’s something else that is a wonderful skill set for reporters, but reporters never use it. It’s okay to be the idiot. How many middle class reporters, white or black, walk into the well of the American underclass and don’t suffer the temptation of showing that they are smart and that they know the answers to questions? Yeah, sometimes you gotta wade through a certain amount of bullshit. But it’s in that waiting that people learn to trust you. Because you’re listening. And also while you’re wading through the bullshit, eventually the bullshit wears out and they start telling you not only what you need to know, but also what they need to tell you.

DEGGANS: Do you still miss journalism? Think you might ever go back to it?

SIMON: I do—at any moment, even to this point, because I’ve never garnered a significant audience in television. I have this remarkable sinecure with HBO that I don’t think I can walk away from. They’re allowing me to tell stories that I think matter and that I think are good arguments. But I think in some respects, once I can’t do the kind of TV I want to do, it is time to come back to journalism. I miss the reportorial. I miss the sense of discovery. I miss the actual going out and being in the sinew of the world. You want to be the guy standing up at the campfire with the best story.

Eric Deggans is National Public Radio’s first full-time TV critic, chair of the Media Monitoring Committee for the National Association of Black Journalists, and author of 2012’s Race-Baiter: How the Media Wields Dangerous Words to Divide a Nation.