Michael Bang Petersen, Mathias Osmundsen, and Kevin Arceneaux, a team of political scientists, don’t concern themselves with what people believe. Belief is a private act, they say. People tend to believe information not because it’s factual, not because it’s based on expert opinion, but because it aligns with their existing worldview. What interests these scientists is the moment when belief turns to public action—when people click “share.”

In the 2016 election cycle, Arceneaux, Osmundsen, and Petersen observed a proliferation of hostile political rumors—an umbrella term encompassing conspiracy theories, misinformation, and malicious amplification of scandals. Many of the rumors circulating online had a political target—Obama is a Muslim, or the Democrats secretly operate a pedophilia ring—but they contained a larger accusation as well, one that went beyond politics and seemed to call the entire political class and social order into question. The stories seemed to be saying: The system is rigged.

In other words, the motivation for much of the misinformation and rumormongering online wasn’t only partisan or strategic in nature. Something else was going on. The scientists concluded that a primary driver was the desire to inflict chaos.

After disinformation was shown to have had effects on the outcome of the US presidential election and the Brexit referendum, Arceneaux, Osmundsen, and Petersen decided to create a system to measure the desire to create chaos. Last summer, their resulting work, “A ‘Need for Chaos’ and the Sharing of Hostile Political Rumors in Advanced Democracies,” received the award for best political psychology paper from the American Political Science Association.

In the paper, which is currently making its way through the review process for publication, the scientists identify a personality trait they call Need for Chaos. To measure it they conducted surveys with 5,157 participants in the United States and 1,336 in Denmark. (Petersen and Osmundsen are professors at Aarhus University in Denmark; Arceneaux is a professor at Temple University in the United States.) One survey question asked:

“I need chaos around me—it is too boring if nothing is going on.” Agree or disagree?

Another:

“I get a kick when natural disasters strike in foreign countries.” Agree or disagree?

And:

“When I think about our political and social institutions, I cannot help thinking ‘just let them all burn.’ ” Agree or disagree?

In response to this last question, 40 percent of respondents did not disagree. The percentage who agreed with other nihilistic statements was also high. Arceneaux, Osmundsen, and Petersen were shocked.

Their work seeks to understand why this nihilism is so widespread. Their paper gives credit to pop culture for picking up on an ambient craving for chaos before political scientists got there. They quote the character Alfred in the 2008 movie The Dark Knight, speaking about the Joker: “Some men aren’t looking for anything logical, like money. They can’t be bought, bullied, reasoned or negotiated with. Some men just want to watch the world burn.”

Likewise, in Fight Club, released in 1999, Tyler Durden rails against consumerist culture: “We’re the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War, no Great Depression. Our Great War’s a spiritual war—our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day we’d all be millionaires and movie gods and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

In June 2017, Richard Spencer rehashed similar rhetoric at a rally for Identity Evropa, a neo-Nazi white-supremacist group:

As the Cold War ended, liberalism and Americanism lost its enemy. It lost its boogeyman. And it began to feel that history was over.… You have no future. You’re an individual, bouncing around on the internet between various consumer choices, social lifestyles, and sexual orientations.… We aren’t fighting for freedom. We aren’t fighting for the Constitution.… We are fundamentally fighting for meaning in our lives.… We are fighting to be powerful again in a sea of weakness and hopelessness. That is our battle.

In their paper, Arceneaux, Osmundsen, and Petersen don’t draw a necessary connection between Need for Chaos behavior and white supremacy or violence. The survey results are based on the “thoughts and behaviors that people are motivated to entertain when they sit alone (and, perhaps, lonely) in front of the computer,” they write. But the scientists do associate the urge to share hostile political rumors with “stronger animosity against the target group.”

Seven weeks after Spencer’s “end of history” speech, the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, exploded in violence. This spring, online disinformation about the covid-19 pandemic gained traction amid the lack of a unified government response, and rumors formed about violent and disruptive instigators in the turmoil of protests sparked by the death of George Floyd. Now the country approaches a divisive presidential election, and the potential for those who crave chaos to wreak havoc is greater than ever. I spoke with Kevin Arceneaux about where the Need for Chaos comes from, how the pandemic is influencing disinformation online, and how journalists can best cover chaos agents in the lead-up to the presidential election. This interview has been condensed from multiple conversations and edited for clarity.

Darrach What do you know about these agents of chaos?

Arceneaux We know that they tend to be younger, a bit more male, a bit better off socioeconomically, like middle class or upper middle class. The racial demographics are overwhelmingly white. So they occupy what people on the outside would see as a privileged place in society, but they don’t feel privileged. In fact they feel abandoned by society, like they’ve lost out.

People high on Need for Chaos don’t have one state. There are lots of ways by which people get there. The one thing they have in common is they want respect and they feel like they don’t have it. They feel marginalized. Even if an outsider might think, “Hey, wait a second, you live in a nice house. You have all these privileges. Why don’t you feel respected?” they will tell you, “I don’t.”

Darrach Why do they feel marginalized?

Arceneaux Maybe in part because social progress has involved recognizing minorities and women, these folks feel like they’re losing the respect that they deserve. The trigger is a feeling of “The way the world was before, it would have been my oyster, and now that’s slipping away from me.”

On a psychological level, people who tested high on Need for Chaos also tend to be higher on certain other measures. For instance, one is Social Dominance Orientation, which is a fancy way of saying somebody who has a worldview that divides the world into “strong” and “weak” groups and who wants their group to be the dominant one.

These folks like inequality. They like hierarchies. They look out into the world and they say, “My group should be at the top—why isn’t it? Why do I perceive it slipping?”

Another track we see is people high in valuing reputation and status, but who perceive that they’re low status. So perhaps there’s a socially awkward loner kid. He is in some sense marginalized, but by his peer group, not by society.

Darrach I read you Spencer’s “end of history” speech. He wasn’t selling his cause as a political fight, but rather as a fight to reclaim meaning in life. Does that strategy seem to be directed toward a similar demographic?

Arceneaux We see that people who score higher in Need for Chaos are more likely to share hostile rumors or to behave in nihilistic ways. That’s true even if we account for personality disorders. It’s not explained away by saying they’re all sociopaths or weirdos.

Just because you win the Cold War and you’re well off doesn’t mean you’re happy. They’re the kind of folks who are bouncing around on the internet, searching for their identity and feeling excluded. So that discourse keys into exactly the kind of animus that these people are feeling.

As the country approaches a divisive presidential election, those who crave chaos may wreak more havoc than ever.

Darrach You included a question on boredom in your survey. Do you tie that back to the feeling that a meaningful connection to the world is absent?

Arceneaux It’s interesting—it doesn’t seem like this is some sort of groundswell that’s coming from actual deprivation, or being on the outskirts of society, or being marginalized in an economic or racial sense. If you have to work two, three jobs to put food on your table, you don’t have time to be bored.

One thing I learned from having to move all my instruction online really quickly is that a number of my students didn’t have reliable access to the internet once they left campus. So even the ability to sit around in your underwear and forward hostile political rumors is also kind of a luxury.

Darrach And instigating chaos will break up the boredom? Give life meaning?

Arceneaux These people seem to have a special sense about chaos having a potential to play a positive, strategic role. Other people would say chaos is a bad thing. These people have a tendency to say, “No, chaos can be useful to me.”

It’s not that they want there to be chaos all the time. Bullies, for example, use different tactics to get people to do what they want. Need for Chaos is a character adaptation. It falls in the middle ground between a personality trait, which is super stable, and a state people have that changes from context to context. People have a disposition that’s triggered by a context. So for people who really care about their reputation, really care about dominance, if you put them in a place where they feel marginalized, this turns on for them.

In a very minor way, what we did was to create the feeling of marginalization in an experimental setup. Psychologists have done this. We had people play a game of catch on a computer screen. At some point, the people they’re playing catch with exclude them. We found it moved people up a little bit on the scale of Need for Chaos. Exclusion makes you feel bad, and maybe you want to get back at people. But among the people who were high on the scale of Need for Chaos, when you put them in the marginalized position, they really act out.

Darrach Is this trait a unique product of the moment we are living in? How much does political and social context play in?

Arceneaux It exists in all times. Think about Holden Caulfield. There are people who are predisposed to say, “I want to throw the Man off,” whoever the Man is. “And the way I do that is screw up everything.”

Look at what’s happened over the past century or so: as inequality increases, you see an increase in discontent, and that discontent isn’t just among people who find themselves at the bottom of the economic ladder.

Fight Club is this interesting story at the end of the 1990s, which now we can sort of look back on almost as a reincarnation of the 1950s—good times were here again, the economy was roaring, the Cold War had ended. But there was also all this dark stuff going on underneath, in terms of banks and the beginning of the growth in income inequality becoming apparent. Fight Club is about taking on these evil corporate entities that are trying to control us through consumerism. It’s a really interesting zeitgeist from that period.

Darrach We are still sifting through the disinformation that played into the 2016 election. Do you identify any social context from that time that would have triggered Need for Chaos actors?

Arceneaux I think that it has to do with the continuing increases in income inequality for the middle class. In this time period we’re seeing things like Gamergate, the rise of white nationalism. People who are directly making the argument, “We used to be in this dominant position”—“we” being white or male—“and now we perceive that it’s slipping. We have to rip the system down and build it back up in a way that puts us back on top.” I mean, that’s what these people are asking for.

So in some ways these two trends over the past twenty years, of increasing income inequality and also increasing diversity, could be responsible for triggering the same sort of outcome.

Darrach Does it also stem from the Obama presidency, then?

Arceneaux I think the data agrees with that, but I should say that the Need for Chaos doesn’t mean the individual supports Trump. I should be really clear about that. What we’re finding, just in terms of chaos, is it doesn’t seem like it’s owned by one political group. It’s broader than politics; it goes beyond politics.

Among those who care about politics, if the status they worry about is being a white male, yeah, I think that we can make the argument that those folks are going to be the people that gravitate to Trump.

Darrach Gravitate to Trump and away from Obama?

Arceneaux I would say away from Obama as well as away from the other establishment Republican candidates. So Jeb Bush, too.

If you want to talk about specific people and their concerns and their worries about why they’re marginalized, I think I can make a case that those particular people would see someone like Trump, or even someone like Sanders, as “Yeah, let’s burn it all down.” But they’re going to be very different people, right? They might both be high on Need for Chaos. But the Trump voter might be different than the Sanders voter.

Darrach Did the agents of chaos you identified affect the result of 2016?

Arceneaux If what we found is correct since 2016, then the answer would be yes, in the sense that these would be the folks spreading all sorts of fake stuff on social media. Not just about Hillary Clinton, but also about Trump. Creating noise. These people would be the exact right people for amplifying Russian propaganda. People still debate about how much of an effect that had on the outcome of the 2016 election, but we certainly know that it was an aspect of the 2016 election.

Darrach And what about the conditions now, in 2020? We are living through a global pandemic, preparing for another election.

Arceneaux We live in a world that has internet and social media and allows rumors and vile memes to travel at light speed. Now put that in a context with an immense amount of uncertainty, and an immense amount of pain, both economic pain and a disease that’s causing death and destruction. I think this might be one of those situational triggers for people that pushes them over the edge and triggers a latent Need for Chaos. I think the pandemic can exacerbate it. You have more people than before feeling marginalized, sitting at their computer, and seeing this as a way to create chaos.

This is going to be a very weird election. You can imagine rumors about the role that China has to play in this, whether or not this virus was invented to take down Trump, whether or not voting is really secure. I’m pretty sure that state agents of chaos, such as Russia, are going to try to do again what they did in 2016. And, in part because of the pandemic, they might have a larger army of folks willing to pass along that misinformation, which then will be dutifully reported on by the mainstream media…spreading it further.

Darrach Much of the recent coverage of the Black Lives Matter uprisings against police brutality has depicted them as chaotic rather than largely peaceful. Minnesota governor Tim Walz referred to the protests as “wanton violence” and “wanton destruction.” Many conservatives blamed antifa members for the rioting that took place, though that has been disproved. What do you think of claims that people are infiltrating the protests for the purpose of instigating violence?

Arceneaux I would say that people who are higher in Need for Chaos do support what’s been termed violent activism, which includes fighting with the police, looting, these kinds of things. Whether they are actually doing that here, I don’t think we can say without data. I would be willing to wager money that people who are high Need for Chaos might have gone out just to create chaos. But, given the broad turnout at these protests, they would be a minor element.

We developed this concept to understand why people share hostile political rumors online, and not why people do other kinds of political activities, such as protests. So a lot more thought has to be put into how Need for Chaos translates into more visible political actions.

Darrach Do you have any sense of what kind of media chaos agents consume?

Arceneaux They tend to sample from all over, not just left or right. They tend to traffic extremist websites that essentially peddle…conspiracy theories. Sites I’d never heard of.

The mainstream sites are boring. You’re not going to get that crazy story to spread that says that Warren Buffett invented the coronavirus, or the QAnon stuff. Where the hell does that stuff come from? The New York Times isn’t writing those stories. They come from chat rooms like 4chan and 8chan. Those are the places where those things are born, and then they get a life by people posting them on blogs and then spreading them on social media.

“Some use conspiracy theories as a tool to hammer away at the foundations of a system that they think needs to fall. They don’t care if it’s true or not.”

Darrach What have you seen on social media since this pandemic started that bears the hallmarks of high Need for Chaos?

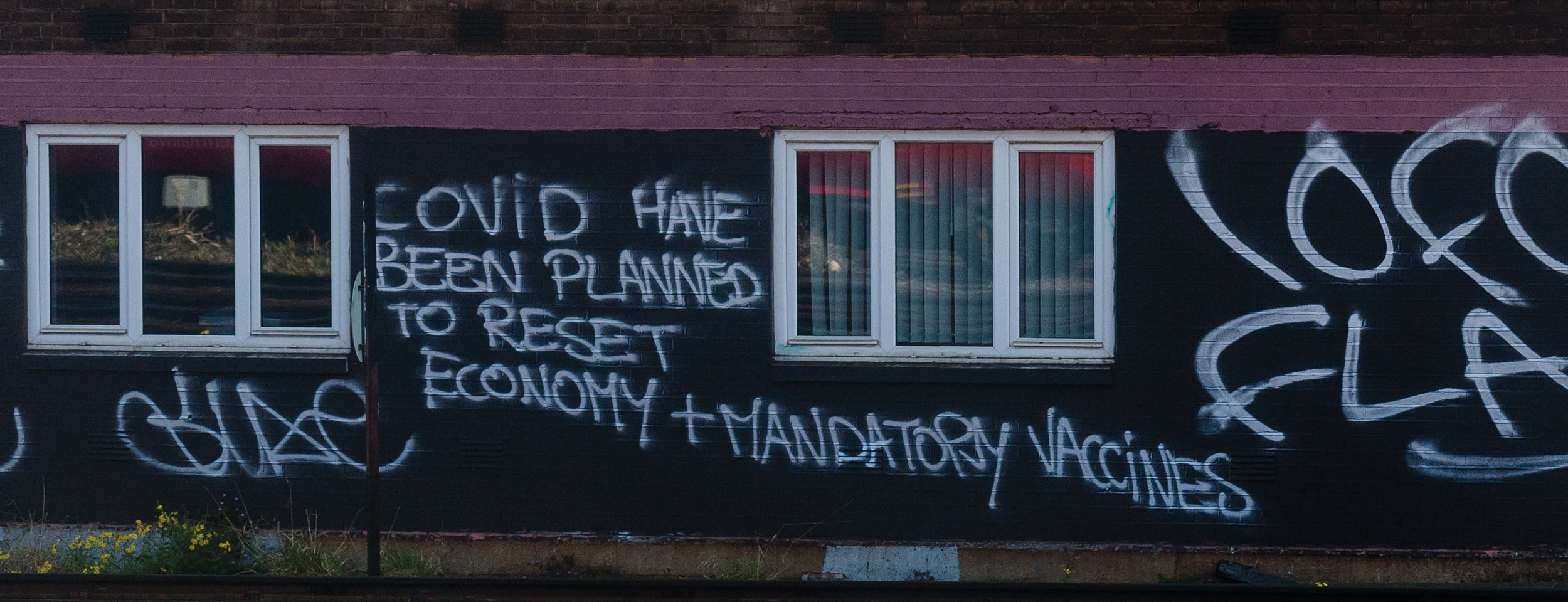

Arceneaux Right now it’s conspiracy theories about the origins of the coronavirus, about how powerful and secretive elites—including the media, of course—are blowing this out of proportion and it’s not as bad as they’re saying, blah blah blah. Those are the things that are going to spread like wildfire.

I’m quite sure that our Need for Chaos folks are sharing those, whether or not they believe them, because they can get eyeballs and create chaos. But it fits their worldview, too. These faceless, horrible elites, trying to screw them over—“let’s create chaos so that we ruin the plans.”

People ask me sometimes why people would believe this crazy stuff when it’s obviously ridiculous. Well, some of them believe it. Some people say, “This is b.s. I shouldn’t be cooped up in my house, I shouldn’t have to wear a face mask.” But some of them just use this as a tool to hammer away at the foundations of a system that they think needs to fall. They don’t care if it’s true or not.

Darrach We’re so polarized right now. You either believe that science is sacrosanct or you believe that this is a plot to dethrone Trump, and there’s not much room in the middle. Does that create more space for high Need for Chaos actors to share hostile political rumors that people will actually believe?

Arceneaux Yes, it does. We know this from our work on ethnic riots. When you’re in a polarized political or even social situation, an “us versus them” situation of intense competition, hostile rumors are more likely to gain traction. That’s largely because there are people who just hate the other side, so either they believe that the other side is doing horrible things or they see, “Ah, this is a useful tool. I can mobilize others to fight against people who are evil, whether I believe this or not. Hillary Clinton probably doesn’t have a child sex ring up in a pizza parlor. But what if I can get people to believe that?”

Even in a pandemic, where you would hope we’d say, “Okay, let’s put all this stuff aside, we’re all human beings and Americans, let’s face this threat together,” there are some people who feel the world is still divided into Team D and Team R. If anything, the pandemic makes it worse.

You have to separate out the people who are high on the Need for Chaos. They’re in their own special box. The rest of us, we’re trapped up in this us-versus-them warfare. And so we can be sometimes used as dupes by these folks who are high Need for Chaos. They are trying to spread rumors, so sometimes they get people who are partisans to believe and transmit their rumors. The motivation of a partisan is an urge to show the world how bad those crappy Republicans, or Democrats, are. The motivation of someone who is high Need for Chaos is just to spread chaos.

Darrach How can the media better respond to chaos agents?

Arceneaux The media focuses on political tactics rather than substance, and that increases political distrust. There is also evidence that when there is a lot of coverage using the term “fake news,” it drives down trust in the media. Then misinformation is no longer the story. More dangerous is the circulation of half truths, or stories where there’s an element of truth with different, tactical framing—it’s powerful in the same way propaganda is powerful. Most importantly, fact checks don’t help except among a very small segment of readers. The real problem is people offline, so it is more effective when the media focuses coverage on who’s spreading misinformation and what their motives are, rather than framing the rumors they spread seriously. Otherwise, mainstream journalists play into the hands of chaos agents. Instead, invert the script. See it as all coming from the same noise machine, and write about the noise machine.

Amanda Darrach is a contributor to CJR and a visiting scholar at the University of St Andrews School of International Relations. Follow her on Twitter @thedarrach.