In the sixties, the population of Clarksville, a small town in East Texas, was 70 percent white and 30 percent black. The area’s economy, long dependent on agriculture, was expanding to include manufacturing, but more than half of Red River County—of which Clarksville is the county seat—lived below the poverty line. In 1965, the Clarksville Housing Authority put up a series of housing projects: two buildings for black tenants and a third for white people. It was a deliberate sorting.

Not long after residents had settled in, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into effect the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which held that the Department of Housing and Urban Development could no longer tolerate racial discrimination in the sale and rental of federally subsidized homes. Over the next decade, the law was tacked onto a growing list of milestones; we were post Brown v. Board of Education, post Civil Rights Act, post Voting Rights Act, post Fair Housing Act and, ostensibly, post-integration. Not in Clarksville, however. Not even close.

Clarksville was divided by Main Street; black residents lived in a small area on the north side, which their white neighbors referred to using a racial slur. A monument in the town square was dedicated “In Memory of Our Confederate Soldiers.” The town’s public housing had become, like other projects across the country, essentially a legally tolerated apartheid system: the white projects, on paved, well-maintained streets, had ranch-style buildings and manicured lawns; the black housing, on unpaved streets, had cracked floors, unvented wall heaters, and decrepit kitchens.

On March 14, 1980, Lucille Young and Virginia Wyatt, two black women, sued the local housing authority and HUD. Young, a mother of six, and Wyatt, a mother of five, had applied for public housing in 1975 and 1978, respectively. Represented by East Texas Legal Services, Young and Wyatt, who had sought residence at the white buildings and were left to languish on a waiting list, asked that the court issue injunctions to grant them entry. East Texas Legal Services arranged for the suit to be a class action, seeking relief for some 40,000 black households in South Texas. US District Court Judge William Wayne Justice approved the request.

Three years later, Clarksville had failed to end segregation in public housing. To solve the problem, the court forced a controversial exchange: 25 tenants in Cheatham-Dryden, one of the all-black buildings, would switch places with 25 in College Heights, which was all-white. This caught the attention of national news media, which in December 1983 produced several dispatches: A Newsday story ran under the headline “Forced Home-Swapping Outrages Races.” The New York Times published a piece, “Desegregation stirs dismay.” A United Press International reporter quoted the town’s mayor, a white man, saying that Clarksville did not have “racial problems”; the article included no voices of black residents.

Consistent throughout the existence of the black press has been denial—just as white society ignored black society, so too did white journalists ignore their black counterparts.

Craig Flournoy, a white reporter working at The Dallas Morning News, was among the reporters arriving from elsewhere to cover the story. He noticed that the articles published by his colleagues at mainstream, predominately white, news outlets lacked historical context about race relations in Clarksville and in the rest of the South. The stories delved little into the discrimination suit, which at that point was three years old; the swap had been, after all, a last resort. As Flournoy read, what stood out most was the characterization of the two housing projects as separate but equal—an assertion he doubted. “The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, The Washington Post—everyone who covered it said the two projects appeared similar,” Flournoy recalls. “They weren’t, by any sense of the imagination.” When he went to visit the buildings, he says. “It didn’t take a friggin’ rocket scientist to figure this out.”

By this time, newsrooms were no longer formally segregated and the nation was decades deep in legislation intended to improve racial politics. But even as legislative advances had begun to usher in, for black and other people of color, a new type of agency backed by the law, advances within news outlets were less than impressive. The beginnings of newsroom integration had little reckoning with the absence of black journalists; instead, there was tokenization, while displays of unconscious racial bias remained evident.

This problem was demonstrated clearly in the assertion, made by many reports, that Clarksville’s housing complexes were identical aside from the race of their inhabitants. Given historical precedent, it was almost sure to be untrue. Flournoy, who grew up in Shreveport, Louisiana, would go on to publish, with his colleague George Rodrigue, a Pulitzer Prize–winning eight-part investigation into government-sanctioned segregation in public housing in Clarksville and other towns in America. But until then, Flournoy found no stories that sufficiently characterized what was obviously unequal housing.

There was one, however, that he missed—a short news article with a niche audience. “Blacks who had to move were apprehensive about relocating,” the story explains. “They don’t know how the White community will react, particularly the older Blacks where the past is pretty much the present in their minds,” a lawyer is quoted as saying. A black tenant adds, “It’s no problem for me living around Whites. I didn’t know that things were that backwards.” The article, which ran without a byline, was in the January 9, 1984 issue of Jet magazine, a renowned black news and culture weekly.

From its inception, the black press has been fighting. Fifty years after the American Revolution, while the country built its wealth and global prominence on the basis of violent chattel slavery, free black people living in northern coastal cities, particularly New York and Philadelphia, came to sense that their ongoing struggle for human rights and dignity would need a platform. Black churches and social societies aimed at self-improvement were not enough to improve the conditions of a people. Newspapers of the time worked against them, by pushing negative stereotypes of both enslaved and free black Americans—as violent, uncivil, and unfit for basic rights afforded to other citizens. Journalists like Mordecai Manuel Noah, the editor of The New York Enquirer, a four-page tabloid, advocated for the transport of free black people out of the US to Liberia; in editorials, he cheered in anticipation of their untimely deaths on the journey.

Early ventures into black-focused journalism began with a collective of prominent preachers, orators, and abolitionists. In A History of the Black Press (1997), Armistead Pride and Clint Wilson II write that, within that group, a newspaper—owned, written, and edited by black people—emerged as a valuable tool “to give free persons of color a voice they otherwise lacked.” Like the newspapers and pamphlets that helped birth a movement for American independence, the black press would serve to unite people in a fight for their lives.

Freedom’s Journal, the first newspaper to be published solely by black people in America, debuted in New York City on March 16, 1827. In a front-page essay, the paper’s editors, Samuel Cornish, a reverend, and John Russwurm, one of the first black graduates of an American college, went to great lengths to distinguish it from existing abolitionist newspapers—controlled by white people who, they wrote, “too long have spoken for us.” Put simply, they continued, “We wish to plead our own cause.” Freedom’s Journal would seek, through the universal attainment of civil rights, education, and character development, to “vindicate our brethren, when oppressed, and to lay the case before the publick.” The men sought to use the newspaper as a tool in pursuit of a common goal—full citizenship and equal rights. They reported on the conditions of public schools in New York; a state asylum for the deaf; the kidnapping and rescue of a child; and the deaths of seven white missionaries in Africa, stressing the need for more “colored” missionaries who, it was thought, were better suited for the “insalubrity of the climate.”

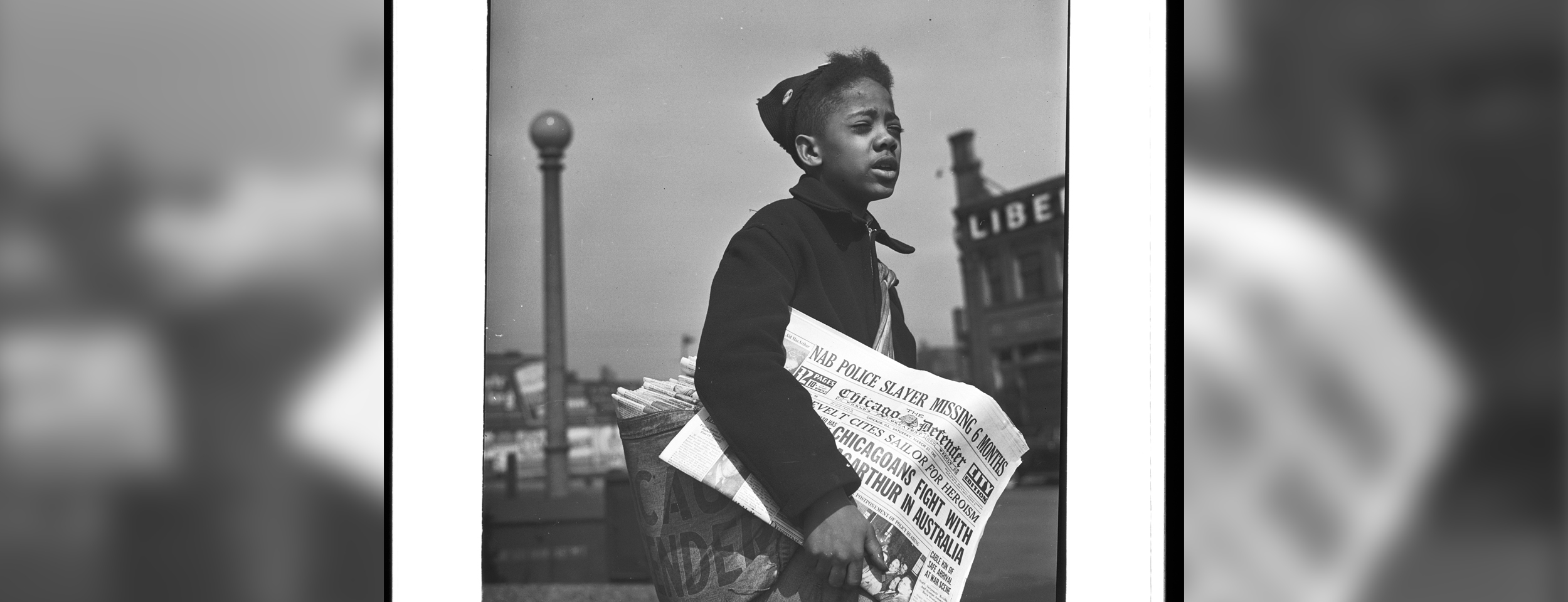

The Pittsburgh Courier built a reputation as one of the most widely read and circulated black newspapers in history by openly crusading for civil rights. Among the battles the newspaper fought—and won—was a 13-year campaign to integrate professional baseball. Photo: Russell Lee, via Library of Congress.

Freedom’s Journal, explicit in its call for black liberation, set the tone for thousands of newspapers that would follow. The state of New York was home to 18 newspapers and magazines that emerged within the first post-emancipation years; more sprang up across the country. Titles included Rights of All, the Struggler, National Reformer, the Colored American, and the People’s Press. The Anglo-African Magazine, founded in 1859 by Thomas Hamilton, ran headlines such as “Effects of Emancipation in Jamaica” and “American Caste and Common Schools.” Hamilton also published a newspaper, the Weekly Anglo-African, that issued an exacting motto: “Man must be free; if not through the law, then above it.” As the black press developed its voice—publishing with conviction against white racism, violence, and hypocrisy—it also covered the tick-tock of African-American life: weddings, births, and deaths that white media otherwise ignored.

The fight for equality in the black press was also incorporated into professional practice. Whereas, through Reconstruction, women could scarcely be seen in most white newsrooms, at black newspapers and magazines, women were on staff: Sarah Thompson, writing for The New National Era before 1900, described the challenges of traveling through the South. Nellie Mossell wrote for black weeklies and edited the women’s department of the New York Freeman. Her book, The Work of the Afro-American Woman, dedicated a chapter to female journalists. Victoria Earle Mathews belonged to the Women’s National Press Association and Lucy Wilmot Smith, who wrote profiles of female reporters for the Journalist (known today as Editor & Publisher magazine) belonged to the National Colored Press Association. Ida B. Wells, born into slavery in Holly Spring, Mississippi, began writing a column for a black weekly under a pen name while working as a teacher and later became editor and co-owner of a black daily. After three of her friends were lynched, in Memphis, she went on to produce the most comprehensive body of investigative reporting on the terror of white lynch mobs in America. Wells also brought attention to the sexual abuse of black women at the hands of white men.

In a 1944 study of race relations in the United States, Gunnar Myrdal, a Swedish researcher, wrote of the role that the mainstream press played in what he called “astonishing ignorance about the Negro on the part of the white public.” Myrdal believed that, for black journalists interested in improving race relations, “To get publicity is of the highest strategic importance.” There could be no doubt, he went on, “that a great majority of white people in America would be prepared to give the Negro a substantially better deal if they knew the facts.” In the study, Myrdal cited Edwin Mims, a white professor of literature at Vanderbilt University who advocated against the practice of lynching; in 1926, Mims had characterized the black press as “the greatest single power in the Negro race.” Myrdal called the black journalists who wielded that power “a fighting press.”

Consistent throughout the existence of the black press has been denial—just as white society ignored black society, so too did white journalists ignore their black counterparts. A textbook on American journalism published in 1941 made mention of black reportage just once, in a passing reference to Frederick Douglass. Whether white society set aside black journalism because of a lack of awareness or a belief in its inferiority, or both, Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff write in The Race Beat (2006), going unnoticed afforded the black press a public forum for radical speech that would have otherwise been impossible. Black newspapers, which espoused a range of political views—some conservative, some militant—enjoyed immense influence within their readership.

The Chicago Defender, founded in 1905 by Robert Abbott, was among the most authoritative. Abbott, who had degrees from Hampton University and Kent College of Law, knew firsthand the struggle that even educated black men in the North endured. As a member of a printer’s union, Abbott contended with stubborn discrimination and was routinely rejected for jobs. As a result, he adamantly opposed suggestions that black people move north to escape white racism and seek gainful employment, insisting instead that federal intervention was needed to improve conditions in the South. In a 1915 editorial, he wrote that it was “best for ninety and nine of our people to remain in the southland and work out their own salvation.”

But a series of events—an infestation of beetles in southern cotton fields that damaged the plantation and sharecropping economy, the slowing of European immigration as a result of World War I that led to new interest in the black labor force, and increasingly violent lynch mobs—compelled Abbott to reconsider. Abbott, Ethan Michaeli writes in The Defender (2016), came to see a mass migration of black labor as an arm of protest against white violence and against the racist Southern economy. He decided to use his newspaper’s influence to encourage people to pack their bags. The front page of the September 2, 1916 edition of the Defender had an illustration—under the headline, “The Exodus”—showing black people “tired of being kicked and cursed,” waiting for a train in Savannah, Georgia. The next month, Abbott endorsed migration in an editorial, “Farewell Dixie-land.”

The Defender went on to aggressively encourage black families to move, publishing positive stories about opportunities in the North juxtaposed with reports of racial violence in the South. The paper ran dispatches from black communities in many states. Thousands of readers wrote in with grateful letters. Circulation boomed, allowing Abbott to expand his staff.

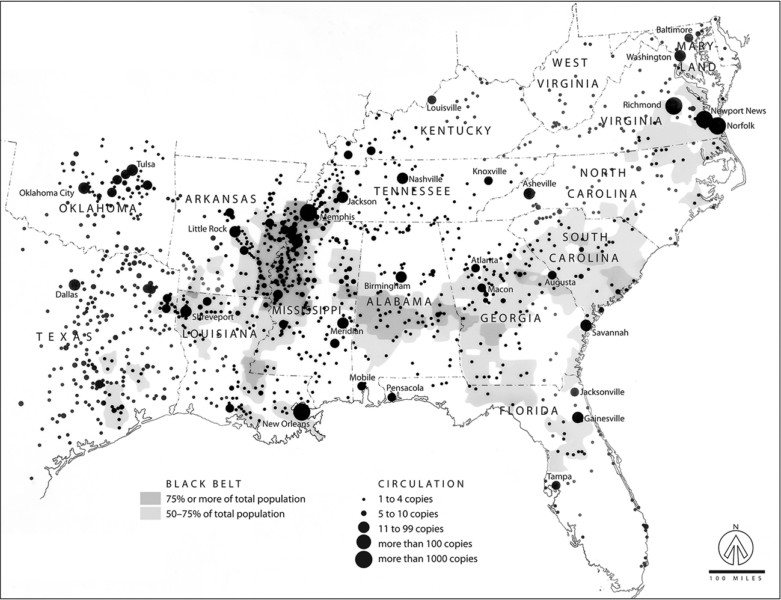

Although it was based in Illinois, the Chicago Defender’s circulation extended well into the Deep South, as shown in the map above, which highlights data from 1919. Copies were brought largely by portermen, along railroad routes. The paper’s endorsement of an exodus from the South is widely credited with ushering thousands of people north and, eventually, west, in a period now known as the Great Migration. Image: Newberry Library.

As black people fled the South, white journalists and state officials lamented the loss, and in some cases violently sought to prevent it. Vendors of the Defender were harassed; the police chief in Meridian, Mississippi, ordered that the newspaper be confiscated. President Woodrow Wilson, noting the national demographic shift, assigned Emmett J. Scott, the highest-ranking black man in the federal government, to produce a report on the causes and consequences of the movement. The Defender’s campaign contributed significantly to what we now refer to as the Great Migration. By 1970, six million black people had headed north and west.

As white media and political leaders have checked in and out of its orbit, the ability of the black press to hide in plain sight has wobbled. Sometimes, black newspapers sought notice. During World War II, the Pittsburgh Courier led a “Double VV” campaign—a twist on Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s campaign slogan, “V for victory,” aiming to draw attention to the hypocrisy of a country willing to fight Nazis abroad but unable to offer equal rights to its own black citizens. The Courier ran editorials demanding an immediate end to segregation, publishing photos of black and white supporters of the cause. Black families across the country posted Double V posters in their windows. In response, J. Edgar Hoover, as director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, dispatched agents to interrogate black editors about their work; he tried (in vain) to charge editors with sedition. The Office of Facts and Figures, the Office of War Information, and the Office of Censorship opened their own investigations. Black newspapers reported unexplained cuts to their supplies of newsprint. The post office began monitoring the distribution of the black press, fearing that the nation’s enemies would use it as propaganda.

Nevertheless, black newspapers and magazines thrived as the fight for equal rights drove readership in the black community. They attracted more attention from white readers, too; in the sixties, as television brought the brutal reality of Jim Crow into every living room, minds opened. But publications of the black press—still a “fighting press”—did not rise, in the consciousness of white Americans, as the papers of record on race relations; black reporters remained, to most people, something else. Pursuit of a “common good,” when it is black, never stopped provoking skepticism.

In the modern age, questions of credibility have followed reporters alongside their coverage of racial justice. On August 9, 2014, in Ferguson, Missouri, an 18-year-old boy named Michael Brown, who was black, was shot by a 28-year-old police officer named Darren Wilson, who is white. Brown died around noon. His body was left in the street for hours; by that evening, his neighbors and friends had assembled a makeshift memorial with flowers and candles laid out on the pavement where his blood had splattered. Protests erupted nearly immediately. By Sunday, Ferguson was on fire, and every major news outlet was on the story.

Wesley Lowery, a black reporter on The Washington Post’s national desk, was dispatched to cover the unrest. At one point, he ducked into a McDonald’s nearby the site of Brown’s death that had become a makeshift press pit. As Lowery sat, checking Twitter while he charged his phone, police entered, some heavily armed. Lowery and Ryan Reilly, a white HuffPost reporter, were asked for identification. Reilly asked the cops why they needed to see ID. The police left briefly, then returned to inform the pair that they needed to leave. Lowery began to record the exchange and, after receiving conflicting information about where to exit, asked for a minute to gather his things. At that moment, several officers moved to arrest him.

Lowery dropped his belongings and tried to offer the police his wrists. But they slammed him into a soda machine, accusing him of resisting arrest. “Ryan, tweet that they’re arresting me, tweet that they’re arresting me,” Lowery recalls saying to Reilly. Reilly never got the chance, because he was arrested, too. Both men were brought to a police station and told that they had been detained for trespassing. They were held only for about 30 minutes. But when they were released from custody, they faced a barrage of criticism. Lowery had become, to his discomfort, a character in the story that he’d been sent to cover. “Once that became the case, there were a series of ways people tried to suggest the work we were doing was illegitimate,” he says. “The first was that I wasn’t a real journalist and after, it was the suggestion that I was too close to activists, sympathetic to protesters, and only asked hard questions of police. There were bad faith attempts amplified by the fact that I was young, outspoken, and black.”

There was a clash, Lowery found, between an abstract American value of a free press and people’s unease with aggressive questioning of institutions, including the police. For detractors, Lowery’s race factored in, too. “They could project their prejudices on me,” he says. “Of course I was biased because how could a black person be fair when reporting on black people? Nobody would argue the inverse.”

“There is this perception that the only person who can be objective is a white man, even though he comes with his own prejudices and background.”

Black journalists like Lowery, once left out of the mainstream press altogether, often still contend with doubts about their grasp on objectivity—the existence of which has no real consensus in the profession. The gradual integration of newsrooms, which began in the late sixties, gave familiar challenges of black journalism a facelift. And even where black journalists—and other people of color—are seen on mastheads, few occupy senior newsroom positions.

At the same time, as economic models in media have changed, or collapsed, many premier black press institutions have lost influence and circulation; some have shuttered. A few historical black newspapers—like the New York Amsterdam News, the Chicago Defender, and the St. Louis American—still publish, if to a diminished readership. Jet and Ebony magazines were purchased by a private equity firm in 2016; the former published its last print issue in 2014, and the latter was sued in 2017 for failing to pay freelancers.

Early this year, for the first time in almost two decades, Essence magazine became fully owned by black people. New black publications have risen on the web: The Root, a division of Univision; The Grio, owned by Byron Allen’s Entertainment Studios; HuffPost’s Black Voices vertical; Blavity, focused on millenials; NPR’s Code Switch, which takes a multiracial approach; and ESPN’s The Undefeated, which reports on the intersection of race and sports.

Danielle Belton, the editor of The Root, finds that the work of telling stories that cover the most vulnerable communities remains a job for the black press. Reports that appear on The Root and its competitors generate attention to problems—like white people calling the police on black people for frivolous reasons—that later become dominant narratives in the mainstream. The distinct moral view of black publications gets transferred, gradually, into universally accepted moral clarity. What that pattern reveals, Belton points out, is that “objectivity” is a false premise—too much gets missed in its name.

“There is this perception that the only person who can be objective is a white man, even though he comes with his own prejudices and background,” she says. “The notion of impartiality, that people can turn all their biases off and report purely, is a fantasy.” She adds, “The difference between The Root and a more mainstream publication is that we are honest with the fact that we bring with us our blackness, our femaleness, maleness, when we are reporting. A lot of people make the mistake of thinking The Root is a left-leaning blog. It’s a pro-black blog.”

But the black press has evolved beyond discrete publications. A network of journalists, bloggers, radio hosts, and other prominent writers have collectively formed a kind of black media moral compass: Nikole Hannah-Jones, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Eve Ewing, Clint Smith III, Doreen St. Felix, along with countless reporters and writers working at local publications across the country without national acclaim. (Jelani Cobb, the editor of this issue, would also be included in any complete list.) Often, it is these journalists providing the most valuable black journalism in the spirit of the “common good” as outlined by the earliest black publications. These writers, unlike their predecessors, are buoyed by interracial confidence in their work being fair and accurate. “When I think about the black press, I think about journalists whose constituency is black people and the advancement and equitable treatment of black people,” Lowery says. “I work for a publication that is national in scope, but my personal constituency is black people.”

Lowery’s job has brought him to cover politics, policing, and other subjects that deal with injustice, often against the black community. In July, Lowery shared a by-line on a series detailing 52,000 murders in America for which no arrests were made; three quarters of those victims were black. “Journalism is about correcting the power imbalances in our country,” he says. “You have people who have been systematically denied power. One of the equalizers is the free press, which can go to the people who are powerful and ask questions on behalf of the people who are otherwise powerless.”

As Lowery speaks about his position, he flips back and forth between identifying as a member of the “free press” and the “black press,” at once identifying the latter as having a distinct history and purpose while demanding its legitimization within American journalism. The “free press” has, since its beginnings, always come with an asterisk—one that has signified outright exclusion, deployment of negative stereotypes (whether conscious or unconscious), disregard for stories affecting black people, and a failure to consult marginalized groups as experts and sources. For black people in journalism, in some sense, doing the work means rattling against accepted norms.

In Lowery’s view, journalism’s pursuit of truth is not at odds with the earliest black publications’ commitment to equity—what happens now is a reckoning with history. “I see my role as applying that pressure on behalf of black people,” he says. “Black people have been promised equality and equity and justice, and if they are not receiving it, it is the role of the black press to apply pressure.”

Alexandria Neason was CJR’s staff writer and Senior Delacorte Fellow. Recently, she became an editor and producer at WNYC’s Radiolab.