Beth Macy is still getting used to the idea of being an expert. Dopesick, her 2018 book, made Macy one of the country’s most authoritative voices on the subject of opioid addiction. The fifty-five-year-old reporter, who is based in Roanoke, Virginia, has shared information about sensitive topics, such as stigma’s stymying effect on medication-assisted treatment, with a range of news outlets. Dopesick provided a complex and compassionate picture of those users, dealers, doctors, law enforcement officers, civic activists, and parents who are weathering a flood of opioids in Appalachia. It was also one of the first major critical dives into OxyContin manufacturer Purdue Pharma and the Sacklers, the family behind the corporation.

Pinning the crisis, which killed more than forty-seven thousand people in 2017, on that company was a particularly nerve-racking experience, Macy says. “The subtitle says, ‘The drug company that addicted America.’ They’re in the news every day now, but back then they weren’t. And I’m laying this out there.”

Macy says her reporting always proceeds from an urge to “mine my own story”—to better understand the people and places her life comprises. Her first book, 2014’s Factory Man, was inspired both by a profile of charismatic furniture factory owner John Bassett III that Macy wrote as a feature reporter for the Roanoke Times and by her kinship with the factory workers of Southwest Virginia, who weren’t so different from the blue-collar laborers she grew up around in Urbana, Ohio. Her second, Truevine, explored the story of two brothers whose albinism led to their kidnapping and eventual forced exhibition in a carnival, and taught her about the exploitation and racism that Black Roanokers were subjected to under Jim Crow.

Macy says the experience she gained writing both books was essential to weaving a comprehensive story about the ever-evolving opioid crisis. “It’s by far been the hardest book,” she says. “I couldn’t have not done the first two, because I wouldn’t have had the confidence to not have had that narrative arc settled at the beginning.”

Recently, Macy spoke with CJR about life in Southwest Virginia, the Roanoke Times, and her love for feature writing. She also talked about grappling with the task of grieving while reporting and the distinctions between activists and journalists (or whether there are any), as well as her recent efforts to suss out what happened to Tess Henry, a Roanoke woman featured in Dopesick who was found murdered in a Las Vegas dumpster after fighting her opioid addiction for six years. Throughout our conversation, the same challenge came up again and again: how to shine a light on opioids while summoning compassion for those besieged by it. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

There is this ongoing sort of discomfort when you go from being a newspaper writer, where you’re not supposed to say what you think, to really spending years on a topic and almost becoming an expert. But in some ways, you’re also asked to be an activist. I’m trying to step into that space, but I’m still a little tentative about it.

You spoke to Longform about the criticism you received after writing “Pregnant and Proud” for the Roanoke Times—how people felt you were condoning teen pregnancy by profiling those girls. Have people been similarly upset about the empathetic way you present people who are dependent on opioids?

The criticisms are on both ends. You have these really conservative people who just think they’re moral failures, that they’re criminals. They can only see the behavior; they can’t see the disease undergirding it. All the way on the other side, you have this very lefty, harm-reductionist community that gets mad when I write about the fact that some of these medicines, these lifesaving medicines, can be abused and diverted. They say any criticism of that at all is not in the interest of public health. Fair point, but I keep thinking back to what I thought in the teen-pregnancy brouhaha, which is, “Don’t kill the messenger.” How can we deal with this problem until we talk about it and get it all out on the table? In some places, where they haven’t had access to good medication-assisted treatment programs, a lot of people have abused and diverted it. That’s a fact.

You could say, “Oh, I should only be writing about safe injection sites now.” And that would make the harm-reductionist people happy. But the rest of the community is so far from understanding that. You kind of have to meet people where they are.

In a recent piece for NBC News, you quoted a civic leader in Mount Airy, North Carolina, who said the city should leave people to die and then harvest their organs.

When you hear that kind of ridiculous comment, your skin [crawls] and you want to run screaming from the building. But we know in these rural areas, where voter turnout is low—in part because of the opioid crisis—her voice gets amplified.

You spoke about Dopesick last fall, in Roanoke, and showed the locket with Tess Henry’s picture in it. You spent a lot of time with her; in the book, you talk about driving her to addiction meetings, walking her baby around in the background while she attended group sessions.

I don’t know how you can write about something this complicated and this sad without spending a lot of time with someone who’s actually dealing with it. I’ve had a little criticism—“She got too close to the subject.” But how else would you get this story?

The first time I interviewed Tess, I was just totally transparent. I said, “I don’t know if this is going to end up being in the book”—I hadn’t even sold the book proposal yet—“but I know that if I spend time with you, I will learn more about this crisis, because I’ve already learned a lot just in our first three-hour interview about all the ways you’re falling through the cracks. Would there be a way we could meet regularly?” And she says, “Well, I need to go to meetings, and I don’t have a way to get there often, because my mom works.” And I said, “Well, I could give you a ride, and we could talk on the way, with your permission.”

Beth Macy (far left) at a book-launch event for Dopesick, with sources (from left) Sister Beth Davies, drug counselor Vinnie Dabney, and Patricia Mehrmann, the mother of Tess Henry. Photo courtesy of Beth Macy.

That only lasted three or four times before she was probably back using again, although she insisted at the time that she wasn’t, and she said she didn’t want to go to meetings anymore. Should I have given her a ride? Did that change the outcome of the story? Perhaps, but it was also in service to the story and in service to the truth.

I was trying to understand how it went from a pill problem to heroin. She just taught me a lot about that. She named certain drug dealers that I could then go to the Roanoke Times and look up. She named a month when the pills got hard to get, where she was like, “I think it was called ‘the upscheduling of hydrocodone.’” I looked up “upscheduling of hydrocodone,” and she was exactly right, she had the exact same month. She taught me what all those headlines look like on the ground level.

There was a moment where she texted me and asked if I’d pick her up from a drug house. She didn’t call it a drug house, but I later learned that’s what it was. “Please can you come get me?” I was like, “Oh, wow, this is where the rubber meets the road. Am I going to go get her?” I felt it was too dangerous. And so I didn’t. Part of me feels like I used her when I needed her, but then when she needed me, I didn’t.

The day she died, I reached out to Carole [Tarrant, former Roanoke Times editor] and said, “Carole, how do I handle it?” And Carole said, “You just have to put your notebook down and be a human being.” What would I do if she was just a friend? I would make Tess’s mother and her family soup.

What kind of soup did you make?

I made chicken soup, but I burned it because I kept calling people, going “Am I doing the right thing?” Patricia Mehrmann, Tess’s mother, thought it was beef—I guess because I burned it. And I brought these rolls that were made for me by the main character of Truevine, Nancy Saunders, who makes me rolls every Christmas.

That person who said you got too close makes me think of journalists such as Lewis Raven Wallace, who are criticizing the notion of objectivity and the idea that good reporting means staying emotionally distant.

It was only one reviewer out of fifty. But, you know, you always remember the negative things, right? You never remember the good things.

There’s this great writer who’s retired now, Washington Post Magazine’s Walt Harrington. He said if you’re not wrestling with what to include and what not to include, and how to behave and how not to behave, you’re not getting close enough. You’re not getting to where the soul meets the bone; you’re not getting to the heart of the matter. There was no trying to get to the heart of the matter with this. It was so raw, so right out there, so full of squishy, ethical problems, almost at every step. I felt like if I was honest with the reader, and I did in my heart what was right, I was doing my job the way I would do it.

We all have biases. This bullshit idea of objectivity—I think being fair and being truthful should be what guides us. I feel like if I’m explaining what I’m doing honestly, you know my biases.

There is this ongoing sort of discomfort when you go from being a newspaper writer, where you’re not supposed to say what you think, to really spending years on a topic and almost becoming an expert. But in some ways, you’re also asked to be an activist. I’m trying to step into that space, but I’m still a little tentative about it.

I recently met Sonia Nazario, who wrote Enrique’s Journey (2006) and is a Pulitzer-winning immigration reporter, and she talked about becoming an activist. She gave me permission. She said, “You’re still out there reporting, and you’re basing your opinions on your reporting.” But I guess I’m still figuring out how to do that and be fair. We all kind of pick how we’re going to frame a story, and that’s so subjective, right? But I get called by other reporters and asked how we should fix the opioid crisis. I guess it’s more calling upon all the research I’ve done, more so than my opinions, but when you see the same mistakes being made over and over and people being imprisoned over and over instead of being offered lifesaving treatment—it’s like I’m hitting my head against the wall saying the same things. And I find myself just getting angry about it. I think about Tess and what I saw up close and how unfair it was. It becomes my responsibility to tell those stories.

Carole said at the beginning—because I was really overwhelmed at the beginning—we went to Local Roots and had a beer and talked about what I was going to do with this book. She said, “It’s not your job to fix the opioid crisis.” As if I could. She said, “It’s your job to make people care.”

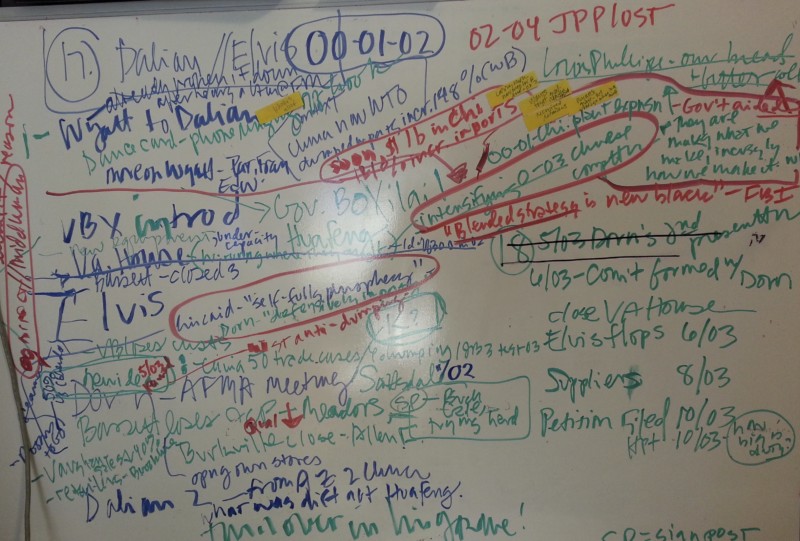

Macy’s outline for Chapter 17 of Factory Man. Courtesy of Beth Macy.

Historic journalists such as Ida B. Wells and Nellie Bly brought themselves into their work, but based their opinions on what to do off of their reporting.

Or [New York Times reporter] Nikole Hannah-Jones writing about integration in New York City schools, and her 1619 project. That all came straight from her reporting, her deep study of history, and her life.

I wonder how much of being a journalist is being an activist inherently. You’re trying to point out a potential problem, and maybe potential solutions, but by writing about it, you’re saying this is a problem that deserves to be fixed. Is that not akin to activism?

I guess it is. I guess it goes back to the teen-pregnancy story. People were so mad at me, right? And yet they got a task force together and they worked on it and their rates came down. They never came back and said “Good job, Beth, for getting us started on that,” but that’s what we’re supposed to do.

Talk to me about your new Audible Original, Finding Tess. What got you started on it?

Somebody at Audible approached [my former agent] about did I want to do an Audible Original, which is kind of the length between a magazine piece and a book. All I could think about was “What happened to Tess?” I didn’t get to get to that in the book.

Before that, Tess’s mother and I, independent of any reporting project, decided over pizza and beer, “Okay, we’re going to go to Las Vegas and we’re going to find out what happened to her.” And the goals were to help the police, who we didn’t really feel were pursuing it, and to try to retrace her final steps. It’s something that will give clues, hopefully, and closure. And I said, “Eventually, I’ll probably want to write about this,” and she said, “Fine.”

We went out in April of last year and we had an amazing trip. What we learned at the end, her world was both better and worse than we thought. We found the person who found Tess’s body. We found somebody who was formerly homeless and addicted, who became our fixer and took us around to these homeless encampments. We found the guy who would take Tess in when she was ready to get clean and let her stay with him. In exchange for what, we still don’t exactly know, but Tess told her mom he saved her life. We went to the places where she was in treatment. We saw it all and met some amazing people. So when the agent came to me, I thought of Finding Tess.

I also said, “Oh, by the way, I have hours of recorded interviews on my iPhone of Tess. Not the best quality, but not bad.” I sent the Audible editors some of my recordings, [which was] a little bit like showing someone your dirty clothes, right? But they needed to see what kind of quality they were, and they said, “Actually, they’re pretty good.” You actually hear Tess in her own voice. We envisioned it as a podcast, both telling her backstory in her own words, then going so much further than the book went. The whole concept being, if we could find out where she fell through the cracks, if we could find out what happened to her, maybe we could explain America to itself—why we’re still in the midst of this terrible crisis and why people fall through the cracks every single day.

What was different about your process in doing the podcast?

I learned that I talk too much. Shut up, let the person talk. And then let the people talk in the recordings. If the tape is good, let the tape lead the way. It was about two hundred and twenty pages, the script, and a lot of it’s quotes.

My favorite part is when we’re interviewing this addictions doctor in Roanoke named Jennifer Wells, and she’s talking about the divide about medication-assisted treatment and how people with addictions get judged and they die all the time because they think they have to get clean on their own, because that’s “the real way to do it.” And she lets out this long sigh, and that sigh contained multitudes. Then she said, “I’m so tired of saying the same things over, but actually I’ll say it forever, ’cause I know it saves lives.”

I think you learn a lot from this one test case. Here’s Tess, this beautiful woman from a family of many means, healthcare professionals, and if she can fall through the cracks, man, anybody out there can fall through the cracks.

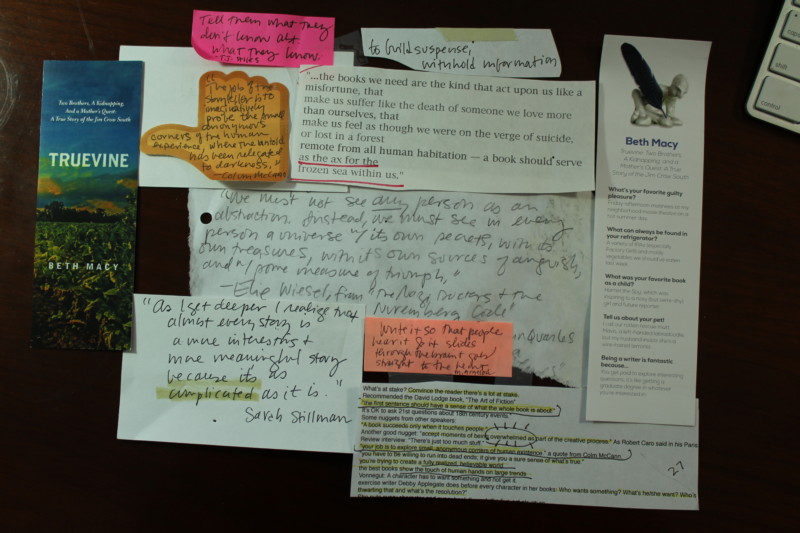

Ephemera from Macy’s desk, circa her second book, Truevine. Courtesy of Beth Macy.

It seems like, for you, Dopesick ended in a lot of grief because of Tess’s death. Not the same kind of grief that her mother suffers, obviously, but still grief.

Totally grief. The book was finished. It had been copyedited, buttoned up. I don’t think it was quite yet in galleys. I emailed my editor and said, “This happened, I’ll have to rewrite the ending.”

I wrote the epilogue in, like, a day. I just sort of vomited it out. And it didn’t change much. But I also …just let Pat, Tess’s mother, guide me. She asked me if I could drive her to the funeral home. And I had my notebook—I always had my notebook out; I didn’t want her to forget I was a reporter. So I took her there, and we went inside, and the person ushered us in to this little windowless room where Tess’s body was, and they had spent two days making her up in order to make her presentable for Pat to view her. She invited me to go in the room with her, and she said goodbye, and I watched her grandfather say goodbye, and then she invited me to say goodbye. And I did. And it would have been awkward to be taking notes, but I did have my notebook out as a reminder. I knew I was going to have to describe the scene. You just go with your gut and try to be a human being first, but try to tell the truth, down to the hard truth that this family was still debating what they should have done about Tess.

Meanwhile, it seems like you’re going to Carole and others, asking what you should have done, and what you should do now.

I’m always sort of checking it—with my husband, with Carole, with my editor, with others. Everybody has their little team of journalistic superheroes cheering you on and giving you advice.

I actually talked to my friend Dr. Frank Ochberg—who coined the term PTSD—because my general practitioner thought I might have PTSD, and I thought, “Well, I know the guy who coined it. Why don’t I just call him?” He’s like, “I think you should go to a psychiatrist, but I think you have secondary trauma.”

We have to take care of ourselves, because it’s hard doing this work. It’s emotionally hard; it can be physically hard. I was having a lot of trouble getting to sleep for a long time. I needed help.

I feel like that’s still a conversation that doesn’t come up often in newsrooms: How do you deal with the emotions that come up in the work?

No, not at all. It’s still very male, right? It has this male, tough-guy swagger thing. Just over the course of my thirty years doing this, it hasn’t changed that much. There’s more women doing the work, but it’s a hard job to do if you’re going to be a mom, because you don’t know your hours. And even like back in the day, in the nineties and stuff at the Roanoke Times, I would get a lot of shit for the stories I wrote about. They weren’t considered as important, because they were social issues. I used to write a column when my kids were really small. I had the highest readership of any of the columnists, but some of the other, male columnists were like, “Nobody cares about her and her kids.” It wasn’t macho to do that.

I remember this columnist, a fellow columnist, just chewing me out—who did I think I was, writing that kind of stuff? Today, if someone did that to me, I would take them down a country road. I wouldn’t put up with that. But I was twenty-five years old, and here’s this forty-year-old man telling me I wasn’t doing my job right and that I didn’t have the right to have a voice.

You’ve mentioned before that a lot of the critical reporting you did that set you up for Factory Man, Truevine, and Dopesick only came about because editors such as Carole gave you weeks or months to report. I’m wondering if you have any advice for reporters now, who are either in newsrooms where that time isn’t available anymore, or who are independent and need to self-motivate.

I think it’s important for everybody to have one thing they’re piecing out in the background, if they don’t have the time, because you always have the time to do something you care about. It doesn’t feel like work if you love doing it. And those things have really driven my career in the last four years.

There was a moment in my Nieman year, which was 2009 and 2010. I was still a newspaper reporter. Shankar Vedantam, who wrote Hidden Brain and is on NPR now, was a Nieman fellow, too. At the time he was a [Washington] Post reporter. Somebody asked him how he had done so many things. He had written a book of poetry. He had written Hidden Brain. How did he do these things? And he said, “When I really want to crank, I wake up at 4:30am and I work on Shankar, five years from now.” Working on these other projects that weren’t for his current employer, spending the first three hours doing that.

When I had the idea to do Factory Man, I went to breakfast with [Roanoke Times reporter] Ralph Barrier. He had written a book and shared his proposal with me. And I said, “I don’t want to write a proposal, ’cause it’s sixty pages long. When am I gonna do that?” And he said, “I wrote mine with a newborn baby in the house. You just find time. You make it.” I wasn’t going to let Ralph tell me that he worked harder than me. I gave myself one week. I woke up every day at 4:30am, and I worked on it every morning and every night, and I had it done by Friday. It worked!

But I wouldn’t have that vast material to draw from had Carole not given me the time to do that big profile of John Bassett in the paper. Right now I’m casting about for my next idea. You need time to do your reporting and follow dead ends and all that stuff.

You mentioned your next book might also be about opioids?

I probably shouldn’t talk about it, just because nothing is firm yet. Literally it’s in the pre-proposal stage now, but part of me doesn’t want to give it up, ’cause it’s ongoing, it’s unfolding. I’ve spent so much time building up these sources and this bank of knowledge. I don’t want to just give it up. You get to feeling a little turfy about it.

Tadhg Hylier Stevens is an independent journalist living in Seattle, Washington. Their work focuses on the media, the LGBT community, and the triumphs and trials facing marginalized communities throughout the US. Follow them on Twitter at @tadhgstevens.