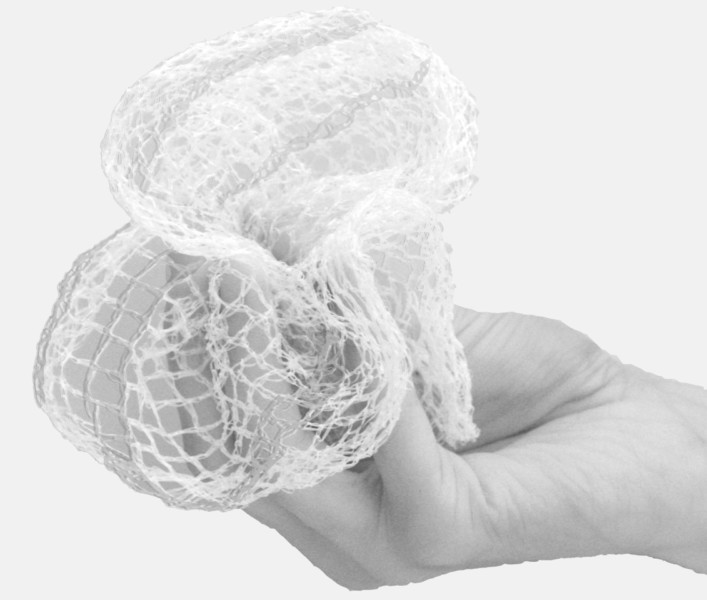

In 2014, Jet Schouten and her colleagues at AVROTROS, a public broadcaster in the Netherlands, embarked on an intricate undercover operation. Their aim was to show how easy it can be to get medical devices onto the market in Europe, and, consequently, inside patients’ bodies. Schouten came up with a fake product, made from the netting used to hold mandarin oranges at the grocery store. She claimed it was a vaginal mesh used to enforce weakened tissue in the pelvic area.

Working with a professor from the University of Oxford, Schouten and her team compiled a bogus dossier on their “mesh,” copied, in large part, from information they found on the internet. They argued, as many manufacturers have done in real life, that their device should be approved by regulators because of its similarity to existing, approved devices. Even if their mandarin net had been a real vaginal mesh, this claim would have been disingenuous—the “similar” devices they referenced had all been publicly flagged as having safety issues, and one of them was not a vaginal mesh at all. Schouten and her team booby trapped their dossier with massive (and made-up) safety risks: attesting, for example, that one in three women using the device would sustain serious, permanent injuries.

The mandarin net “implant.” Photo courtesy Jet Schouten.

Schouten then submitted the application to regulators. In Europe, devices are not approved by government agencies but by private “notified bodies.” Rather than being regulated like drugs, they qualify for the same, looser safety certifications as commercial products like teddy bears and toasters. The notified bodies draw revenue from manufacturers, including medical device-makers, who typically want their products approved at the lowest cost to them and with as little delay as possible. “I started negotiating with them. I told them, ‘I want this price and I want it tomorrow,’” Schouten remembers telling the notified bodies she approached, all of which, she says, were reputable. When they haggled back, she would reply, “I have a different notified body and they gave me a better price. Why should I choose you?”

In the end, not one of the notified bodies Schouten approached questioned her product’s alarming safety data. “They didn’t ask us one question about the product, they didn’t even want to see the product,” she says. The regulators only pointed out a few fixable “non-conformities” in their dossier; for example, that they hadn’t translated information into the required number of languages. The only major stumbling block the team met was that it had not, as is legally required, submitted to a factory inspection. “We’re journalists, we didn’t have a real factory,” Schouten says.

The story, not surprisingly, attracted widespread attention. After it won an award for investigative journalism in the Netherlands and Belgium in 2015, Schouten received a congratulatory email from Joop Bouma, a veteran Dutch newspaper reporter. (“When I started in journalism, I always used to clip out articles,” Schouten says. “I kept them in a binder, and then at some moment in time, I was like, these are all from Joop Bouma!”) Bouma is a member of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, or ICIJ, the global network of reporters and news organizations that burst into the limelight with its work, in 2016, on the Panama Papers.

“We’re journalists, we didn’t have a real factory.”

After getting in touch over email, Bouma and Schouten went hiking and talked about the potential for a global look at the medical devices industry. Bouma said he would take the idea to Gerard Ryle, ICIJ’s director. Ryle was interested. Schouten submitted a written proposal, then drudged through months of research to prove the story had enough merit to proceed. Finally, in November 2017, ICIJ gave the green light, and began to marshal more than 250 reporters across 59 news organizations and 36 countries for the biggest-ever investigation into an industry responsible for the life or death of millions of people around the world. Yesterday, its partners began a coordinated, worldwide drop of their findings.

Medical devices—like vaginal meshes, pacemakers, and breast implants—make up a $400 billion worldwide industry. Devices often don’t undergo rigorous clinical testing: sometimes they’re tested on animals like sheep or baboons, other times patients themselves are the guinea pigs without ever knowing it. Device makers, too, have long evaded serious scrutiny, even as many of their products have been found to be faulty. ICIJ found manufacturers have paid out at least $1.6 billion to settle charges of corruption, fraud, and other regulatory violations over the past decade. Johnson & Johnson alone spent even more than that compensating patients. And Medtronic, the biggest company in the world that makes devices only, has faced serious allegations on four continents, including fraud and price gouging (it denies wrongdoing).

The dangers with these products often aren’t reported to regulators; even when they are, there’s no coherent international system to alert doctors and patients to potential problems. A globalized medical industry works in their favor. Faulty devices often stay inside patients—and on the market—in one country long after another has seen fit to withdraw them. While the US has better safeguards, and makes more data available, than other countries, its system is still severely flawed. A Food and Drug Administration (FDA) database that tracks suspected problems with devices—including, prominently, insulin pumps, hip implants, and spinal cord stimulators—is clunky for patients to use and far from comprehensive, effectively allowing industry players to mark their own homework.

ICIJ found more than 1.7 million injuries and 83,000 deaths potentially linked to devices since 2008. “I started this project because I wanted to create an awareness that medical devices are not only a problem in this country or in that country. Devices go global,” Schouten says. “What journalists do is they check, what are the stories in my country?” In mid-October, Schouten watched on in a darkened black-box studio in Hilversum, a media hub southeast of Amsterdam, as her colleague, Antoinette Hertsenberg, filmed segments for a documentary that will air tonight as part of the Dutch contribution to the ICIJ effort (Bouma’s newspaper, Trouw, is also involved). Hertsenberg was explaining grim statistics as they flashed, in the bright font of a spy movie, across a gossamer screen in front of her.

Jet Schouten. Courtesy photo.

Schouten sat the other side of the screen, checking data on her laptop. She was dressed in neat leather shoes, dark jeans, and a knitted sweater worn under a baggy black blazer, her cropped hair curling just above the collar. Before getting into TV, Schouten worked in radio. Before that, she was an academic, co-writing a book about the theological underpinnings of the work ethic.

While ICIJ brass pulled the strings of the global project from Washington, Schouten remained its beating heart. She took frequent calls from partners around the world, talking them through problems that frequently had nothing to do with her own slice of the project. “I find it very impressive that at the origin of this investigation, this enormous machine, was one extremely determined journalist who wanted to inform patients,” says Stéphane Horel, a journalist with Le Monde who worked on the project’s French chapter.

For the past five months, CJR embedded inside ICIJ’s investigation: listening in on conference calls, spending time with Schouten in the Netherlands, and talking regularly with ICIJ staffers and partners in 10 other countries, from Canada to Lebanon. The result is a picture of a massive journalistic collaboration—a critical new muscle for journalists everywhere. CJR heard repeatedly that the project ran amazingly smoothly given its size and international scale, which added reportorial and data-crunching muscle, then lent a megaphone to the findings.

When ICIJ published the Panama Papers in 2016, its collaborative model seemed like a bold departure from the old logic of fierce competition. Two years later, pooling resources across organizations no longer feels so novel. News organizations the world over are struggling financially; many have folded, those that survive often have such slender resources that ambitious investigative work is beyond their means. In the Trump era, meanwhile, some outlets, especially in the US, have started to see each other less as rivals and more as allies in the face of vicious rhetoric attacking the media as a whole. ICIJ’s success with the Panama Papers—not to mention its Pulitzer Prize for the work—no doubt fueled this trend, too.

The devices project nevertheless was a departure, and a risk, for the group. ICIJ gained global renown and increased the scale of its operations through its work on leaks. This was its first large-scale project since then based on public records and shoe-leather reporting. (The project was also, possibly, the biggest ever journalistic collaboration of this type, period.) The group will now have to watch to see if a consumer affairs story, albeit one highlighting the deaths of patients, can land with the same impact as the scandalous secret dealings of the world’s super-rich, a particularly tough ask in a hyper-charged news cycle dominated by US politics.

When ICIJ published the Panama Papers in 2016, its collaborative model seemed like a bold departure from the old logic of fierce competition.

“The draw that the leak cachet has can be enormous. This time, we’re in a world without that automatic entitlement to the reader’s attention—because we’re bringing them something that had been kept secret from them,” says Simon Bowers, who coordinates ICIJ’s European partners from London. “We’ll see how that goes. It’s obviously a harder thing to say, Well why exactly are you doing this now? It’s a leap of faith.”

The offshore leaks did not fall into ICIJ’s lap in finished form: it took immense effort to make them searchable for partners in an easy, and secure, way. But those projects did, in a sense, have a headstart compared to the devices story—not only did the leaks have inherent news value, but reporters knew the data they needed was inside waiting to be unlocked. The devices story, by contrast, had to be stitched together from what one ICIJ staffer called a “patchwork quilt” of inconsistent public records. “We had 13 million documents for the Paradise Papers,” says Ryle, ICIJ’s director, of the organization’s second big offshore investigation. “It’s much easier to convince media partners to do a story like that than to say, We have a working theory here, but we need documents, we’ll try and find them.”

It took more than six months of preliminary digging before ICIJ approved the devices project. The task for Schouten was to show that the story was truly global—with problems in different countries linked by a single failing system. Once ICIJ decided to go ahead, the project picked outlets from more than 30 countries.

Some of the same organizations that worked on the offshore leaks bought in again, including The Guardian in the UK, Le Monde in France, and Süddeutsche Zeitung in Germany. The Associated Press expressed interest at the instigation of Michael Hudson, its new investigative editor who had, until recently, worked for ICIJ; ICIJ reciprocated, in part, because of the AP’s strong record of reporting on the FDA. NBC News, too, was invited to join after approaching ICIJ. The New York Times, which did not participate in the Panama Papers but did participate in the Paradise Papers, was not involved this time. (While ICIJ has a collaborative model, once it invites a major partner into a project it often avoids inviting a direct competitor from the same country.)

In April, ICIJ hosted partners from around the world in Washington, DC, to workshop story ideas and set a timetable for the project. The summit was an overwhelming moment for Schouten. “I saw this whole group finally all in one room,” she says. “I understood that it’s going to really happen, that now there are over 200 journalists.”

On a conference call in mid-September, Fergus Shiel, project manager at ICIJ, scratched into a notepad on the table in front of him. Behind him, someone had scribbled a list of countries on a whiteboard: the UK, France, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Andorra, China, Croatia, Latvia, Malaysia, Singapore, and the UAE (and those were just the legible ones). Slightly higher up, tacked to a wall, was a postcard depicting a cartoon cat and a message: “Keep calm and be cool.”

After starting his career in Ireland working for local newspapers, Shiel moved to Sydney, Australia, where he balanced journalism work with side hustles, ushering at a movie theater and working in construction. He spent more than 20 years with The Age, a daily in Melbourne, editing its tablet edition before joining ICIJ last year and relocating to DC in March.

Fergus Shiel. Courtesy photo.

The devices project was Shiel’s first with ICIJ. He acted, in part, as its institutional memory, flagging trends and links in the global story and connecting reporters around them. He was also chief troubleshooter. “We have meetings where it’s 5am in one place and 10pm in another, neither of which is conducive to clarity of thought, really,” Shiel says. “That’s one thing. The second thing is language. There’s also cultural differences… Then there’s libel law. So, for instance, you can say things in America which you can’t say in Europe, and certainly can’t say in Australia or Ireland, without being sued.” (Shiel was not the project’s lawyer, but he did help ensure that stories could float both in Europe, where powerful people and companies can injunct reporting they don’t like, and the US, where they cannot.)

ICIJ communicated with partners on the project on regular conference calls, which partners used to share findings and joint reporting opportunities, and pep colleagues up at moments of low morale. A lot of reporting action, meanwhile, happened on the iHub—a byzantine, encrypted portal where partners could ask each other questions and upload new findings. Some participants were overwhelmed by the sheer density of information on the iHub; they compared it, variously, to a bazaar, a runaway New Yorker subscription, and a train you chase as it’s leaving the station. “It’s all there—anytime, anyone can log on and read up on Finland or Germany,” said Matthew Perrone, the AP’s FDA reporter, in June, plucking two random countries out of the air. “You see the great work other people are doing and you’re like, I gotta go find something. It’s like a fire under you.”

Rather than enforce frequent deadlines, ICIJ insisted that just two dates be set in stone: October 12, when reporters could start to seek comment from industry and regulators (preferably through ICIJ), and November 25, when findings would start to roll out simultaneously to heighten the project’s impact. These dates were set at the April project meeting in Washington; since then, partners in several other countries have joined the project, while a few have fallen by the wayside.

“You see the great work other people are doing. It’s like a fire under you.”

While partners worked on their own stories independently, ICIJ, in the words of one staffer, acted like a “wire service”—preparing its own package, including an overview story, for distribution to, and republication by, partners. Every word was checked, every stat verified. At any news organization, that can be a tense process. At ICIJ, keeping stories alive and interesting amid a thicket of technicalities provoked especially lively debate. “To try and wrangle the overview, the global perspective on the device industry, into a shape that is digestible, that is evocative, readable, that is entirely accurate, that does justice to the complexity of the issue… has been extremely, extremely hard,” Shiel says.

For the project to work, reporters in as many countries as possible needed to show how manufacturers get their devices to the market, how they handle reported device flaws (or don’t) once they get there, and how devices get recalled and/or withdrawn from the market. Throughout the project, reporters in Europe found it difficult to get their hands on data related to every part of this process. And if the Europeans had a hard time getting data, partners in Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East often found it all-but impossible.

Europe is a regulatory hub for the devices industry, and the continent exports much of the lax oversight that Schouten exposed in her mandarin net story: manufacturers in other parts of the world, seeing Europe as a soft touch, have been known to test out high-risk products, in particular, on the continent, then seek approval there. If they’re successful, they can return to their home regulators with a European safety certification, which can make local approval easier.

The European Commission, which is the policy arm of the European Union, is notoriously opaque and bureaucratic; “It’s like Fort Knox,” Schouten says. European partners thus had to ask national-level governments for data on a continent-wide system. Some countries (Norway, for example) were more forthcoming than others. Schouten says Dutch authorities denied one of her requests, citing European privacy rules, only for the French government to hand the same data over to her colleagues. Since notified bodies are private, meanwhile, a lot of information about the device approval process lies beyond the scope of freedom of information laws.

“We did FOI the world, basically.”

In the US, reports of suspected problems with devices, known as adverse event reports, are made publicly available through the FDA’s MAUDE database (MAUDE stands for Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience). Since MAUDE’s public interface only allows users to view 500 reports at a time, ICIJ needed access to a more complete set of data. A team led by Emilia Diaz-Struck, ICIJ’s data editor, found a backdoor on the FDA’s website with over 5 million records stuffed behind it.

Each record consists of a checklist, which manufacturers are supposed to use to report basic information, as well as space for a more detailed description of the suspected problem. To complicate matters, the checklist and description sometimes contradict each other; the latter, for example, might detail a death that the manufacturer neglected to flag on the checklist. Sometimes, descriptions contain awkward synonyms—“expired” instead of “died,” for example—that make them hard to scan for keywords. Common variations in device and company names, as well as routine spelling mistakes, are a hazard, too: Diaz-Struck found more than 180 differing references to one type of heart device in the data, for example. In addition to cleaning up the reports, ICIJ’s data team wrote a computer program to crawl through the prose descriptions for hidden nuggets.

They also created two user-friendly interfaces to help partners search the FDA database (which mostly contains US records but also has some international data) for information relevant to their reporting. (“We like to work with great journalists, but we don’t require them to be data journalists,” Diaz-Struck says.) Diaz-Struck and her team also built an ambitious database for the public, showing which devices have been recalled in a given country, and, crucially, which have not been, despite being withdrawn elsewhere.

To build the public database, Diaz-Struck and her team stitched together patchy and disparate recall data from many different countries, all of which store the information differently and make differing amounts of it public. “We did FOI the world, basically,” Diaz-Struck jokes. In Mexico alone, reporters submitted more than 900 freedom of information requests. In response, authorities yielded information on only two recalls. When data was forthcoming, it was often vague—sometimes lacking key information like a manufacturer or device name, or even the level of risk associated with a product. And because devices currently lack unique identifier numbers that stay the same across borders, matching one country’s recalls to another’s was tough.

Though they got there in the end, work on the database continues: it currently contains data from 11 countries, a number ICIJ hopes will eventually be closer to 40. Even then, the database won’t be anywhere near comprehensive. Over 80 percent of the world’s countries will not be in it at all. And the device industry is plagued by the problem of under-reporting, meaning that some red flags simply never come to the public’s attention. “No one can say precisely how many people are injured, maimed or killed by these devices around the world,” says Shiel in an email. “Not regulators. Not manufacturers. No one.”

ICIJ was founded in 1997 by Charles Lewis, an American investigative journalist who previously founded the Center for Public Integrity in the late 1980s. ICIJ was initially a project of the Center, but disentangled itself last year after outgrowing it. At the time, Poynter reported that pressure on ICIJ to lay off staffers, despite its recent success and rapidly rising profile, was a key impetus for the split, with ICIJ keen to solicit and set its own funding. (Both the Center and ICIJ are non-profits.)

In its 21 years of existence, ICIJ has always sought to tackle problems that cross borders, especially those exacerbated by globalization, like tobacco smuggling and climate change. In recent years, the group has become synonymous with investigations into global tax evasion and avoidance. In April 2016, it dropped the Panama Papers, which drew on a massive leak from inside Mossack Fonseca, a secretive Panamanian law firm, to expose the tax affairs of a posse of world leaders and their associates. Tax authorities the world over pledged to clean house, and the Icelandic prime minister, who appeared in them, stepped aside amid a public outcry. In 2017, ICIJ won a Pulitzer Prize for the story. This year, Netflix optioned a movie about it, with Steven Soderbergh in the director’s chair and Meryl Streep, Gary Oldman, and Antonio Banderas lined up to star.

Just over a year ago, ICIJ followed up the Panama Papers with the Paradise Papers, a second offshore leak, this time mostly from inside a different firm, Appleby. While the Paradise Papers implicated further high-profile individuals—from US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross to members of the British royal family—the stories landed with less immediate impact. As CJR wrote at the time, however, the project nevertheless was important. By proving the Panama Papers were not a one-off, ICIJ showed users of offshore tax structures that they can no longer take secrecy for granted, and would-be whistleblowers that they can leak masses of sensitive data without getting caught.

ICIJ has not abandoned the offshore beat. “If we had had another Panama Papers that was going to be as good or possibly even better than the previous one, of course we’d have done that. The reality is, we don’t,” Ryle, its director, says. Nonetheless, its pivot to medical devices was a conscious departure. As senior reporter Sasha Chavkin puts it, “We wanted to show that we are a leading global investigative newsroom and we can do great stories whether or not someone gives us documents. One reason that we’re sustainable at ICIJ is because we can do different kinds of stories… in terms of subject matter and… in terms of reporting process.”

Chavkin says a previous ICIJ investigation he worked on, examining how projects funded by the World Bank displaced millions of the world’s poorest people, was a template of sorts for the devices project (the World Bank story was published in 2015, but Chavkin still sometimes posts updates). The devices story, however, has involved many more partners than its antecedent—making it a test of ICIJ’s ability to scale up a project based on shoe-leather reporting and public records.

The devices project has a different texture from much of ICIJ’s past work in more ways than just its sourcing. As Shiel puts it, “There’s an appreciation that, broadly speaking, the offshore industry is, if not illegal, at least unethical. But with the medical device industry it’s quite different because the truth is the medical device industry saves a lot of people’s lives, it makes a lot of people’s lives better.”

“One reason that we’re sustainable at ICIJ is because we can do different kinds of stories.”

According to Shiel, a reporter working on the project in the US now needs a medical device himself after he was knocked off his bike at an intersection a few weeks ago; two partners in Europe, meanwhile, suffered heart problems and may also require them. “This is one of the things about the medical device industry: even the reporters who are reporting on the industry as we speak are, in some instances, actively requiring a medical device,” Shiel says. “The universality of the devices and their importance to people has been…” He pauses. “We’ve lived it. It’s an odd thing. When you start focusing on devices you see how ubiquitous they are and how important they are.”

Even before ICIJ began to seek comment on its story, regulators and industry figures got wind that an impending bombshell was about to hit. Some have acted in advance of publication to soften the landing. Last week, DC lobbyists with the trade association AdvaMed hit back, accusing ICIJ of distorting the facts around medical devices—many of which are perfectly safe—and of using its model of coordinated worldwide publication to stoke panic among patients. (In a statement yesterday, AdvaMed said ICIJ’s stories “counterfeit” implants’ life-changing potential.)

ICIJ is clear it won’t disburse medical advice to patients who come to them with worries: before readers can access its public database, they have to read a disclaimer advising them to contact their doctors with questions. Nonetheless, “there’s just a real lack of information and knowledge about medical implants and their safety out there… People don’t know how their devices are tested, they don’t know how they’re approved,” says Ben Hallman, ICIJ’s lead reporter. “If the takeaway from this, from a patient perspective, is they simply know to ask more questions than they would otherwise, I think that’s a pretty good result.”

The leaked databases behind the Panama and Paradise Papers projects were, in a sense, democratic; any reporter anywhere in the world could search them for prominent local figures they suspected might be squirreling cash offshore. The devices project, by contrast, centered more on Europe and North America: By one estimate, between a third and a half of the reporters working on the project were in Europe.

The devices project exposes how decisions made in the developed world have a knock-on effect in poorer countries. In particular, while devices move around the world, no similarly global system has emerged for reporting problems with, or recalling, faulty devices, then communicating adequate safety information to doctors and patients. “The developing country aspect of this story is interesting because Europe and the US have a bigger responsibility, not just that the system has to be fixed for their own people, but for the rest of the world that is relying on them,” says Scilla Alecci, who oversaw the project’s Asian partners out of Washington.

While past reporting, by Schouten and many others, has raised awareness in Europe and the US, ICIJ’s investigation has broken fresh ground in parts of the world where the industry had, until now, escaped scrutiny. “In India, this is virginal territory,” says Ritu Sarin, investigations editor at The Indian Express.

“Even the reporters who are reporting on the industry are, in some instances, actively requiring a medical device.”

Working with reporters and news organizations in less economically developed countries—and countries that lack a free media—leads to unavoidable disparities in the output different partners can produce. Andras Petho, one of the last crusading reporters left in Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, told CJR in August that he was struggling to contribute to the project as his access to official information was so poor. “I was hoping that this was going to be different,” he said. “But the relationship between the government, the state agencies, and the remaining independent media has deteriorated to such a low level that even pursuing a story like this—which is not about oligarchs, it’s not about politics—we cannot really get help or cooperation.”

Rather than lean on challenged outlets, ICIJ seeks to lift all boats, lending them reporting resources and investigative capacity beyond their usual means. While Petho did finally get hold of some Hungarian data in October, he says his story was considerably strengthened by his ability to tap into partners’ research.

Alia Ibrahim, a co-founder of Lebanese news website Daraj, had a similar experience. “We have access to the international information and then add local reporting, looking for cases, looking for human stories. But the big chunk of the work—when it comes to validating the argument, the hypothesis, all that—is already done,” she says.

Daraj’s site launched on November 3, 2017; two days later, it was part of the global drop of the Paradise Papers. Ibrahim says Daraj was the only Arabic-language publisher on that project (this time it’s working with organizations in Tunisia and Jordan). When the son-in-law of the speaker of Lebanon’s Parliament sued Daraj in the wake of the Paradise Papers, Ibrahim felt ICIJ had her back (in any case, a judge threw the suit out). “Being part of an international investigation, we can kind of just—quote, unquote—‘blame’ it on the bigger organization. It gives us a unity we really need,” she says. “This is not a minor detail for us.”

“In India, this is virginal territory.”

Differing accountability climates worldwide mean partners have different expectations about what impact their work might have. While Ibrahim says many partners around the world were “waiting for the earthquakes that are going to happen once they publish,” in Lebanon, by contrast, “I could give you 100 examples of how investigations proving corruption, proving malpractice, didn’t lead to anybody being held accountable.”

In the US and Europe, the project has already started to have impact: FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb instantly promised a substantial overhaul of the device approval process, while doctors’ groups and government agencies in France, Spain, and the Netherlands issued new recommendations, for example around breast implant safety. Wherever in the world partners are based, however, they are all reporting on a giant global system with giant global flaws. It is, obviously, unrealistic to expect that system to disintegrate, or to right itself, at all—let alone overnight.

With that in mind, partners all over the world do not see this week as the end—or even the beginning of the end—of the devices project, but rather as a milestone on a longer journey. While some partners extracted whistleblower testimony, the project was built mostly from publicly available information. Now that the story is out in the world, Ryle hopes it will catch the eye of well-intentioned industry insiders with secrets to share, thus propelling further reporting. Besides, he says “we’ve educated a whole bunch of journalists on a new topic.”

Back in the black-box studio in Hilversum in mid-October, Schouten watched on as Hertsenberg, her colleague, interviewed Madris Tomes, an American expert on the medical devices industry. Tomes worked as an analyst at the FDA before leaving to found a company, Device Events, that scrapes the FDA’s database and repackages it into a more robust and user-friendly interface. While ICIJ’s French and German partners filmed interviews with Tomes at her home in Pennsylvania and in Washington, DC, respectively, Schouten’s team flew her to Europe so she could use its high-tech projection screen. “I think she is the only one outside the FDA who really understands the data, who really understands how to connect the dots,” Schouten says. “There are only a few worldwide who are really aware of it.”

As Tomes and Hertsenberg filmed a series of segments on a wide variety of topics related to the global devices landscape, graphics—from bar charts to human avatars, implants throbbing red under their skin—appeared on the projection screen in front of them. Tomes explained how weird synonyms for death, such as “expired,” make FDA data harder to analyze. She then talked through summary reporting, or an old process whereby US regulators would only count each individual report of potential problems with a device, even though each report might contain many separate incidents.

Antoinette Hertsenberg (left) and Madris Tomes (right) film a segment for AVROTROS. Photo: Jon Allsop.

Hertsenberg kept interrogating Tomes’s US-specific knowledge for her Dutch viewers, asking, for example, whether certain US rules should be replicated in the Netherlands. At one point, off camera, Hertsenberg and Schouten asked Tomes to contextualize a local finding about vagus nerve stimulators, which are commonly used to regulate seizures in epileptic patients. Tomes could not, off-hand, so she logged into her Device Events system to search for stats on the devices. Tomes came back with a 40 percent rate of reported potential problems in FDA data.

Taking the devices project global hasn’t just enabled Schouten to inform patients beyond Dutch shores of the unknown risks they run when they put implants in their bodies. It’s given her—and hundreds of reporters who previously knew little to nothing about the devices industry—an in-depth understanding of a global system that lurks in the shadows while compromising public safety; an understanding that most doctors lack.

Working with ICIJ has also exposed Schouten to a worldwide community of investigative reporters who make routine work of exceptional journalistic collaborations. “You have all these people who are completely obsessed,” she says. “They’re completely driven, they’re very, very talented. They’re maniacs. I love that. You never have to explain why you don’t watch Netflix.”

Jon Allsop is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, and The Atlantic, among other outlets. He writes CJR’s newsletter The Media Today. Find him on Twitter @Jon_Allsop.