In 1921, when Arizona was less than a decade old and had fewer residents than Newark, New Jersey, the state’s department of roads was directed to put out a magazine. While the legislation that apportioned funds for the publication, titled Arizona Highways, imagined that it would “encourage travel to and through the state of Arizona,” the engineers who initially oversaw the magazine took the name more literally, printing maps of the state’s thruways and articles explaining the numbering schema for its roads. It wasn’t until mid-century that the initial promise of Arizona Highways was fulfilled: a glossy monthly delivering awe-inspiring photographs of the Grand Canyon State to more than a half million subscribers nationwide.

Today, Highways is the most beloved publication in Arizona. It has become an institution in a state too young to have many, as likely to be cited by historians and policymakers as any newspaper. For residents, the magazine is a talisman of their state’s particular allure. I’ve seen bundles of meticulously maintained back issues at a library sale in Flagstaff and vintage covers framed on the walls of an Airbnb in Phoenix. The reverence Arizonans have for the magazine is rooted in its upward trajectory over the course of the twentieth century, one that matches the rise in stature of the state itself from an obscure wasteland to a place of universally acknowledged natural splendor and cultural vibrancy.

NEW AT CJR: Nonprofit newsrooms are keeping their heads above water

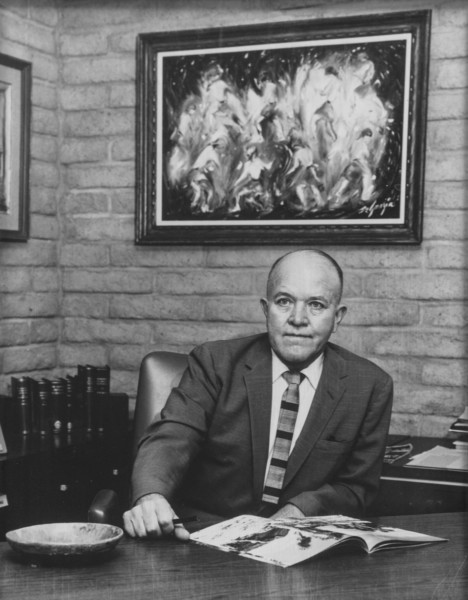

Robert Stieve, the current editor of Highways, calls it an “anomaly.” No other state-operated tourism magazine has reached the same heights of national influence, nor spawned as many imitators. (Texas Highways, which was founded in the seventies, is the closest.) Stieve credits this success to the editorship of Raymond Carlson, who led the magazine for over thirty years. When I visited Stieve at the Highways office in Phoenix this February, he interrupted our conversation several times to rummage through drawers, cabinets, and bookcases for ephemera Carlson left behind—a yellowed letter from 1965, a photocopied editor’s note, a snapshot—and offered each as evidence of a single man’s effect on an entire state’s image.

Editor Raymond Carlson in his office. Courtesy of Arizona Highways.

Carlson’s strength was his sense for how the tastes of readers were changing with the times. As popular culture progressed in visual media, from radio to film and then television, photography became the magazine’s calling card. Highways was the first consumer publication to print an all-color special edition, in 1946. Other issues from that era included a Kodachrome image of Navajo National Monument, an Ansel Adams photo of Monument Valley, and a vertiginous shot of a waterfall pouring through Havasu Canyon—all of them made, as Carlson put it, “more real and poignant” by the addition of color.

The magazine’s circulation at the time of Carlson’s arrival was ten thousand; by the fifties it had grown to more than one hundred seventy-five thousand. Readers, it seemed, couldn’t get enough of the full-color landscape photography that Carlson was publishing with increasing frequency. While monthlies like Life popularized photo-essays for a general audience, Highways had a more specific purpose: to, as Carlson wrote in one editor’s note, “describe life in the west and tell you why that life is more attractive than life is elsewhere.” He worked with many of the period’s most renowned nature photographers: Esther Henderson shot a number of features on the Petrified Forest and gold-leafed palo verde trees; David Muench captured the brilliant, fleeting bloom of an ocotillo cactus; and Norman G. Wallace framed the Superstition Mountains behind a stand of saguaros.

Esther Henderson, 1968. Courtesy of Arizona Highways.

Meanwhile, tourism in Arizona soared. Between 1938 and 1949, spending by visitors to the state rose by 300 percent, and some of these guests were so taken with Arizona they never left. By 1960, the state’s population had more than tripled from the Depression era, to 1.3 million. For many visitors and eventual residents, the magazine provided an introduction to Arizona; more than 90 percent of Highways’ subscribers lived out of state. Win Holden, a former publisher of Highways, recalls a childhood trip to visit his grandmother in Michigan in the 1950s, during which he noticed a copy of the magazine on her coffee table. The cover featured a saguaro. “I made a typical five-year-old comment, like, ‘C’mon, there’s no tree like that!’ ” Holden says. “And instead of telling me I was a moron and to go to my room, she said, ‘Well, let me show you.’ ” They went through the magazine page by page; Holden was enthralled.

In 1965, Inez Robb, a nationally syndicated columnist, called Highways “habit forming.” If the magazine exuded “a faint tincture of snake oil” to skeptics in the Northeast, Robb wrote, it was only because “Arizona shares with the giraffe the distinction of having to be seen to be believed.” It wasn’t just Arizona’s mind-bending landscape and flora that commanded the attention of readers like Robb; it was the astounding feats of human ingenuity that were enabling the state’s population boom. The magazine devoted an issue to the Central Arizona Project—the massive aqueduct that provides Colorado River water to the state’s southern cities—in which Carlson wrote, “The handiwork of the engineer is felt in every phase of our environment that makes living genteel, safe, and comfortable.” An article titled “Dream Homes by the Dozen” bragged that Phoenix’s already sprawling subdivisions offered buyers “as much as thirty-percent more house and luxury features” for the same money they’d spend elsewhere.

Highways was not only intent on showing its readership the beauty and grandeur of Arizona, it was also making an argument for the arid state’s newfound livability. People around the country responded: by the end of the century, the state’s population surpassed five million. As Robb wrote, once you got “hooked” on the magazine, “You begin to believe and then you want to go, go, go…”

Ray Manley, 1985. Courtesy of Arizona Highways.

Pick up an old copy of Highways and it’s not hard to see why mid-century readers found it so captivating. The size, for one, was unusually large—until the early 2000s, Highways had a nine-by-twelve trim, ample space to showcase centerfold landscape photos. Its layouts were slick and modern, and it frequently carried bylines from eminent figures like Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas and Frank Lloyd Wright.

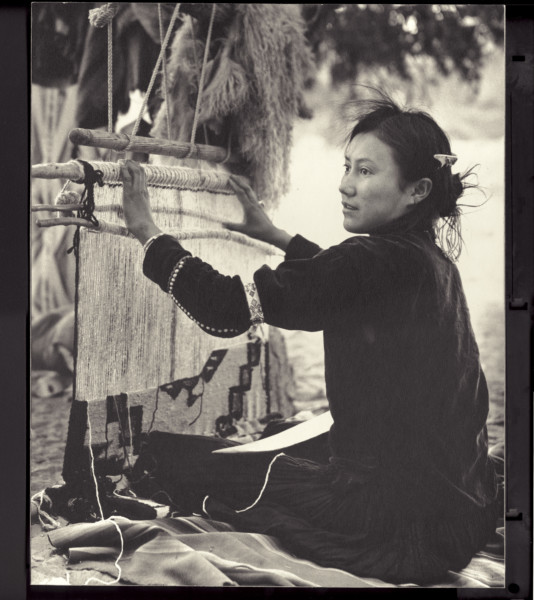

At the same time, Carlson’s project of making Arizona palatable for monied retirees often compartmentalized the state’s Hispanic and Native populations, consigning them to a sideshow of indigenous “culture” that had little to do with portraits of easy life in Mesa and Chandler. Stereotypical images of “Mexican hat dances,” mariachi bands, and rusticated Indians litter the magazine’s archive. Barry Goldwater’s gloss on a portrait of a Navajo man he took in 1938 is typical of the approach of many early contributors: “I didn’t speak Navajo, and he didn’t speak English. So he was just sitting there, and I just picked the camera up and took the picture, gave him a cigarette and that was the deal.” While there were a few early attempts to give these communities a genuine voice—most notably a 1950 issue that featured work by Andy Tsihnahjinnieand Allan Houser, two of the period’s most influential Native artists—the magazine had little interest in giving room to Hispanics and Native Americans in the version of Arizona it was selling to the world.

Not that its readers minded the whitewashing—Highways’ circulation surpassed five hundred thousand by the mid-1970s. That peak came shortly after Carlson’s retirement, a demonstration of how the reputation of the magazine developed under his editorship far outlasted his tenure. In 1986 the New York Times published a glowing profile of Highways, and the magazine was able to carry on in the pattern Carlson had set until the end of the century. However, by the time Holden became publisher, in 2000, Highways was losing as many as a quarter of its subscribers every year.

“I’ve got three, four million people in my backyard who don’t want to be armchair travelers,” Stieve says. “They want to be experiential travelers.” After he was hired, in 2006, Stieve went to Holden with an idea to reconceive Highways as a magazine that drove local tourism. Today, there are reviews of restaurants in Phoenix and itineraries for day trips from Tucson, and each issue includes a hike of the month and a scenic drive. Before Holden retired, in 2018, he and Stieve also bolstered the magazine’s finances by cashing in on the Highways name, licensing rights to a local TV show and a gift shop in the Phoenix airport. They even persuaded the state’s legislature to approve a special Highways license plate, which has made the magazine $5 million over the past decade. This brand leveraging, along with some tweaks to the magazine’s format—dropping the trim size and reintroducing advertising for the first time in decades—has put Highways on secure footing. Even its circulation, which had dipped below one hundred eighty thousand, is finally on the upswing.

Joseph Muench, 1957. Courtesy of Arizona Highways.

Still, it’s hard to avoid the feeling that Highways’ best days are behind it. The magazine does little to correct that impression—rather than the forward-looking boosterism of Carlson’s time at the helm, in recent years the magazine has taken on a decidedly retrospective feel. New issues include a “This Month in History” box with facts dating to the nineteenth century. Anniversaries are dutifully marked with commemorative issues, including this April’s, which celebrated the magazine’s ninety-fifth year. Even new articles can seem tethered to the past; Stieve authored a recent essay about rafting the Verde River, a story whose genesis was a pitch Carlson originally received in 1950.

Stieve is well aware of the risks he runs by emphasizing the Highways legacy. “You don’t want to be doing reruns all the time,” he says. “You don’t want to be TV Land.” One signal of Stieve’s ambition to avoid that fate has been the magazine’s recent attempts to correct for its past treatment of Native and Hispanic Arizonans by inviting contributions from members of those communities. Stieve spoke with particular pride of an essay he’d commissioned from Danielle Geller in which she wrote about learning traditional Navajo weaving techniques once practiced by her great-grandmother.

Stories like Geller’s, as well as the occasional article gesturing at the threat climate change poses to Arizona’s splendor, have an urgency to them that’s lacking in many issues of Highways. Still, this is a tourism magazine, and the focus remains on rendering Arizona in as attractive a light as possible. “We’re a landlocked state,” Jeff Kida, Highways’ photo editor, says. “Our borders aren’t going to shift. How do you look at the same acreage differently? How do you present it differently?” Arizona Highways has survived the great unraveling of the magazine industry, but the state it extols is already a far different place from what it was even twenty years ago. If Highways hopes to recapture the dynamism of its golden years, it will have to return its focus to anticipating just what the future Arizona might look like.

MSNBC PUBLIC EDITOR: Covering a post-policy world

Kyle Paoletta is the author of American Oasis: Finding the Future in the Cities of the Southwest, which will be released by Pantheon in January. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.