Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

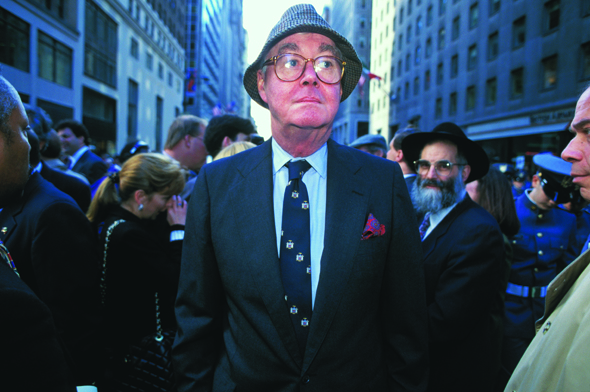

In the open Daniel Patrick Moynihan walks through a Columbus Day Parade crowd in Manhattan, 1994. (James Leynse via Corbis Images)

The ease with which the United States government creates new state secrets masks the ultimate cost of the secret’s production. Once minted, a secret must be guarded lest a spy sneak in and pluck it from the bunch–or a Chelsea Manning, an Edward Snowden, or a lesser leaker with a security clearance release it into the wild. Vaults must be built, moats dug, and guards hired, trained, and paid. Add to that the cost of routine audits, to make sure nobody has picked the locks, and the expense of the annual security clearances for the spooks, bureaucrats, and IT specialists who make, sort, use, and maintain the secrets. At last count, nearly five million people in the US were cleared to access Confidential, Secret, or Top Secret information, a number that includes both government employees (like Manning) and contractors (like Snowden).

Official secrets have been reproducing faster than a basket of mongooses thanks to the miracle of “derivative classification,” and this rapid propagation has compounded the maintenance costs. Whenever information stamped as classified is folded into a new document–either verbatim or in paraphrased form–that new derivative document is born classified. Derivative classification–and the fact that nobody ever got fired for overusing the classified stamp–means that 92.1 million “classification decisions” were made in FY 2011, according to a government report, a 20 percent increase over FY 2010. Once created, your typical secret is a stubborn thing. The secret-makers’ reluctance to declassify their trove is legendary: In 1997, 204 million pages were declassified, but since 9/11 only an average of 33.5 million pages have been declassified annually.

The secrets glut imparts another cost, one that can’t be measured in dollars, as Daniel Patrick Moynihan warned in his 1998 book, Secrecy: The American Experience. Just as excessive economic regulation blocks efficient transmission of the market’s supply and demand signals, the hoarding of secrets locks vital knowledge away from politicians, policymakers, and the public, who need the best information to conduct informed debates and make wise decisions. However difficult the quandary when Moynihan was writing, it’s much worse now. By FY 2011, the volume of new classified documents created annually had risen to 92 million from six million at the time Secrecy was published.

While Moynihan nurtures a civil-libertarian sentiment, his primary thrust is utilitarian: The stockpiling of too many secrets renders the nation less secure, not more, because it forces us to make decisions based on poor-quality information. In our attempts to blind our adversaries, he points out repeatedly, we end up blinding ourselves. The information blackout also hinders the public’s ability to hold the secret-keepers accountable for what they do. Kept too close to the vault, important secrets don’t get properly vetted, which results in policy being sent off course by “incorrect” secrets. (“The mistakes, you see, were secret, so they were not open to correction,” as historian Richard Gid Powers puts it in Secrecy‘s introduction.) Secrets prevent sympathetic legislators–here Moynihan was writing about his relationship with President Ronald Reagan–from defending a colleague’s foreign-policy positions without knowing what they are. And finally, the routinization of the classified process, this willy-nilly banging of “Secret” on the most banal documents, creates a surplus of secrets that increases the difficulty of protecting the vital ones.

Moynihan died in 2003, a few years after completing three terms as a Democratic senator from New York. If he were still serving on the Select Committee on Intelligence, one can’t imagine the certified anti-communist and self-identified hawk applauding Manning and Snowden for loosing the secrets they vowed to protect. But one can easily imagine Moynihan leading a seminar on secrecy mania, waving thumbdrives and CDs to symbolize the gigabytes of classified information the two leakers so easily pilfered and distributed, and decrying the government’s secrecy fetish.

Although they’re portrayed as leaking twins, both in their 20s, Manning and Snowden robbed the secret works of two different classes of classified material. Although Manning held a Top Secret clearance, like 1.4 million other people, none of the hundreds of thousands of files he leaked to Julian Assange’s WikiLeaks organization were of the Top Secret grade; he shared Confidential and Secret pages exclusively. Snowden, on the other hand, gave Top Secret documents to The Washington Post and The Guardian from the very beginning. Manning’s leaks revealed the contents of State Department diplomatic cables, dossiers on the detainees at Guantánamo Bay, and incident reports from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan–hundreds of thousands of documents constituting the government’s paper trail. While the Manning leaks were stoppered at several hundred thousand documents and their effect contained, Snowden’s ongoing leaks vex the government at a higher level–because he’s still sharing stuff and because his leaks expose the very architecture of the NSA’s global surveillance machine.

Both leakers have been called traitors and accused of weakening their country. In late 2010, shortly after WikiLeaks steered Manning’s leaks to The New York Times, The Guardian, and other outlets for publication, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton denounced those leaks as “an attack on America” and “the international community.” Manning was eventually convicted of espionage and other charges, but US officials conceded privately several weeks after Secretary Clinton’s blast that the harm had been minimal. In a puckish column, the Financial Times‘ Gideon Rachman declared that the Manning disclosures had done the United States a great favor. Far from damaging the State Department’s credibility by disclosing its internal discussions, the leaks demonstrated the consistency of its diplomats’ public and private statements. Assange deserved a medal, Rachman suggested, because the diplomatic cables depict American foreign policy as principled, intelligent, and pragmatic. “That was, perhaps, the best-kept secret of all,” he wrote.

There’s no such perverse comfort to be found in the Snowden materials. They portray a deceitful government, sluicing into view the blueprints for the surveillance state. The leaks flow on as I write this, including details about the successful efforts of the NSA to compromise cryptography in our computers and phones and undermine security on the internet. The NSA’s surveillance operations, a foreign and domestic hydra, qualifies as the “vast secrecy system almost wholly hidden from view,” to select one of Moynihan’s salient phrases. In their haste to contain the Snowden revelations, the nation’s leaders have repeatedly lied to the public about what telephone and email messages they intercept, store, and read, and how that information is used.

“Secrecy is a form of regulation,” Moynihan declares in his opening sentence, restricting what information citizens may possess about their government and the actions performed in their name. Unlike economic regulation, whose dimension can be gleaned from reading the US Code and scanning the Federal Register, the shadow cast by secrecy is fundamentally unknowable to few outside the government elite. Writing elsewhere, Moynihan stated, “Normal regulation concerns how citizens must behave, and so regulations are widely promulgated. Secrecy, by contrast, concerns what citizens may know; and the citizen is not told what may not be known.

On occasion, the national security establishment will even prevent the president of the United States from being read in on the secrets elemental to the performance of his office. In the late 1940s, the US Army’s Venona project cracked the codes the Soviet Union was using to communicate with its spy network in America, Moynihan reported. The decryptions were shared with fbi Director J. Edgar Hoover and other members of the national security brotherhood, but General Omar Bradley concealed them from President Harry S. Truman because his White House was known to leak. Venona gave an accurate picture of Soviet penetration of the US. Had the secrets been made public–the Russians had learned by then that they’d been found out–the nation might have been spared the poisonous squalls about domestic communism exhaled by Senator Joseph McCarthy. Of the Venona decryptions, that were finally made public in the mid-1990s, Moynihan writes:

Here we have government secrecy in its essence. Departments and agencies hoard information, and the government becomes a kind of market. Secrets become organizational assets . . . . In the void created by absent or withheld information, decisions are either made poorly or not made at all. What decisions would Truman have made had the information in the Venona intercepts not been withheld from him?

Moynihan arrived at his secrecy-state critique after working inside the beast. A versatile academic, he rose to political prominence as a counselor to President Richard Nixon, who appointed him ambassador to India in 1972. Later, he served as United Nations ambassador under President Gerald Ford, before winning his Senate seat as a Democrat in 1976. His skepticism of official Washington assessments formed in secret ripened in the 1970s, when the government continued to tout the Soviet Union’s growing power. It was obvious to Moynihan that such an economically anemic country couldn’t last long, a sentiment he expressed in Newsweek in 1979. In the mid-1990s, Moynihan gathered his political clout to help lead a legislative movement to establish a federal commission on government secrecy, which he chaired. The commission’s staff interviewed convicted spies, historians, journalists, officials at 96 agencies, and others in the completion of its mission. Its final report, delivered to President Bill Clinton in March 1997, recommended strict statutory limits on what could be declared secret, among other things. For instance, a demonstrable need to protect the information in the interest of national security must exist; classified designations must “sunset” unless recertified by the agency as a continued secret; formal procedures for the classification and declassification of information should be established.

Moynihan wrote Secrecy as an expansion of his appendix to the commission’s report, and his book includes a novella-length introduction by historian Richard Gid Powers, which spackles some of the gaps in the senator’s review of the century-long expansion of Washington secrecy. Moynihan and Powers trace our government’s passion for secrets to the Wilson administration’s paranoiac views about dissent during World War I, and its passage of the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, which established the secrecy bureaucracy and in its early incarnation dictated press censorship.

The Russian Revolution and Moscow’s establishment of the Communist International, pledged to world revolution, further rattled the American state. The domestic communist conspiracy, such as it was, never threatened the US government. The overreaction to the subversives, who never numbered more than a few thousand, ran through the Cold-War era, sustaining a culture of secrecy designed to keep the populace dumb and frightened. Excessive secrecy kept the public from learning that the United States suffered no “missile gap” with the Soviets; that the Bay of Pigs invasion was doomed; that the Vietnam War was built on lies and deceit; that the Soviet Union was disintegrating. Excessive secrecy, Powers wrote, gave bureaucratic cover to flawed policies and failed careers inside government. It also gave the government a weapon to “stigmatize outsiders and critics.” Had Truman been able to draw on the secrets stash, he could have arrested America’s paranoia about the internal communist threat by speaking the truth about the pitiful weakness of Soviet spies. But because he was in the dark, too, he couldn’t directly refute the alarmists. “[McCarthy] was able to gain hearing for his fantastic charges only because he could claim that the evidence to support them was kept hidden by the executive branch,” wrote Powers. This damming up of information has created what Powers calls “postmodern paranoia, an aesthetic preference for ‘alternative’ modes of thought that leads to playful interest in conspiracy theories about government secrecy just for the hell of it.” In other words, the rationing (or regulation) of information creates a market for misinformation.

Leaning on the work of Max Weber, Moynihan explained how secrecy and bureaucracy inevitably became enmeshed. It doesn’t matter whether the bureaucrats are spooks or briefcase-toting paper-sorters, the bureaucratic culture “will always tend to foster a culture of secrecy.” Bureaucrats bury and guard their secrets, keeping “knowledge and intentions” hidden whenever (and for however long) they can, because keeping others in the dark gives them power. Without a doubt, the decade of secret spying by the NSA has given it palpable power over Congress, the other agencies, and the public, who wouldn’t tolerate the systematic intrusions if kept informed. Keeping legislators in the dark increases the bureaucracy’s power, Weber taught, a lesson the NSA applied to Congress. Snowden’s leaks have done less damage to the NSA’s ability to snoop than they have to its bureaucratic power. For the first time in almost four decades, the agency finds its authority questioned and scrutinized. It’s telling that the NSA’s first response to the Snowden revelations was to insist that its actions may have been secret but they were defensible because they were lawful. The government deployed the word when the Snowden materials helped reveal the bulk collection of domestic phone logs, the searching of Americans’ email and text messages, and the surveillance of internet browsing via the XKeyscore program by the NSA. That lawfulness, however, depended on legislation passed by Congress, interpreted (liberally and secretly) by the nsa, monitored by Congress in secret, and overseen in secret by the FISA court. Moving laws off the public books and into the shadows where the governed cannot view them is something only a self-protecting, self-perpetuating bureaucracy could think up.

There’s an air of optimism to Secrecy, a sense that with the Cold War behind us and no real military enemies facing the US, the eight decades of secrecy shackles could be sprung without any hysteria. If, as Randolph Bourne famously wrote, war is the health of the state, then terrorists are the health of secret-keepers. The attacks of September 11 restored the American secrecy cult. The battlefield extends from home to foreign mountain ranges, and the war is fought in both real and virtual space. Your phone, your computer, your internet connection, the algorithms used to do your banking online have all been drafted into the state’s secret and escalating war on Al Qaeda. Thanks to Snowden, we now know about the government’s secret cyberattacks, its secret giant gulps of internet traffic, its secret databases of your data, and its secret cracking and compromising of encryption. Aided and abetted by a secret FISA court, the last two presidential administrations have normalized privacy intrusions and eavesdropping, with no end in sight as long as one fanatic plots to set off a bomb somewhere.

Presaging the government’s response to 9/11, Moynihan distilled this template for government’s action during and after wartime in a passage about America’s extravagant post-WWI spychasing:

Note the pattern set in 1917. First twentieth-century war requires or is seen to require measures directed against enemies both ‘foreign and domestic.’ Such enemies, real or imagined, will be perceived in both ethnic and ideological terms. Second, government responds to domestic threats with regulations designed to ensure the loyalty of those within the government bureaucracy and the security of government secrets, with similar regulations designed to protect against disloyal conduct on the part of citizens and, of course, foreign agents.

Moynihan was no secrecy nihilist. He believed in “legitimate and necessary” military secrets, but wanted much of the culture of secrecy the spooks depended on to be replaced with open approaches to intelligence questions. “Analysis, far more than secrecy, is the secret to security,” he wrote. Open inquiries, in Moynihan’s view, independent of the bureaucracy’s control, and critiqued, debated, and verified by other open-source researchers, would produce the best results. Had we insisted on such an inquiry of Saddam’s weapon programs, perhaps we could have been spared the second Gulf War.

At the conclusion of his book, Moynihan gets lippy, denouncing the secrecy machine:

A case can be made . . . that secrecy is for losers. For people who don’t know how important information really is. The Soviet Union realized this too late. Openness is now a singular, and singularly American, advantage. We put it in peril by poking along in the mode of an age now past. It is time to dismantle government secrecy, this most pervasive of cold war-era regulations. It is time to begin building the supports for the era of openness which is already upon us.

Those ready to be convinced that open inquiry can crack the security nut won’t find satisfaction in Moynihan’s book. He waxes vague on how analytics would replace a system of secrets. In his most concrete example, he suggests that commercial satellites could break the stranglehold over aerial intelligence that government satellites have given to the spooks. Closer to earth, he does his position no favor by claiming that a public poll conducted in Cuba before the Bay of Pigs operation should have been enough to persuade the CIA that an invasion wasn’t likely to lead to an uprising against Fidel Castro.

Moynihan’s critique of the century-long expansion of institutional secrecy didn’t convince the bureaucracy that secrecy has failed to make the United States secure, or that it would continue to fail. The book, and Moynihan’s investigation, attracted positive reviews and approving editorials in The Washington Post and The New York Times, plus feature coverage in the Los Angeles Times, as Judge Robert A. Katzmann noted in his book Daniel Patrick Moynihan: The Intellectual in Public Life. But for all Moynihan’s pungent anecdotes, his thesis that secrecy makes us less secure isn’t very testable. Too much information remains classified for us to judge the effectiveness of secrecy; too little material has been declassified for any counterfactual histories built from them to be persuasive. His book plots no strategy for the repeal of the secrecy state, and he didn’t rally civil libertarians, journalists, academics, and politicians to advance the reforms his commission proposed. He was like a doctor who diagnosed a malady, suggested a round of medication, and then moved on to the next patient.

Secrecy barely changed the policy debate and did no lasting damage to the secrecy culture. The book hasn’t been forgotten, just dismissed, with its most visible proponent in recent months being columnist George F. Will, who has referred to it twice. Any residual optimism Moynihan’s book may have created expired on the morning of September 11, 2001. Since that catastrophe, the intelligence bureaucracy has acquired greater powers and bigger budgets to chase foreign and domestic enemies, and gained a whole new set of secrets and secrecy tools.

As Moynihan repeatedly points out, war and the threat of domestic disorder, is the health of the secrecy state. “We make policy by crisis, and we particularly make secrecy policy by crisis,” scholar Mary Graham told The New York Times in early 2003, predicting that the temporary emergency powers then being approved would last at least for 20 years, “just as we lived with the Cold War restrictions for years after it was over.”

To read Secrecy now is to despair. As long as threats exist against America and opportunistic legislators hold office, there appears no practical way to roll back the secrecy bureaucracy. In the summer of 2013, when emotions against the NSA intrusions were highest, a bill to limit the agency’s powers to collect electronic information was voted down in the House of Representatives. Maybe I’m impatient, but if Snowden’s revelations aren’t enough to convince Congress to sand a corner off the secrecy establishment, I doubt if anything on his computer drives could.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.