Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

On January 8, Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752 caught fire in the sky above Tehran. All 176 people on board the flight died in the incident, the cause of which was not immediately known. The next day, the New York Times published a 20-second video clip which showed the explosion was caused by an Iranian missile. The video refuted statements by Iranian officials that such a cause was “scientifically impossible.”

“We first learned that it was a missile that took down a Ukrainian airliner over Iran because of this video showing the moment of impact,” a Times staffer explained in subsequent coverage. (On Tuesday night, the Times team updated its reporting based on new video evidence, from which they concluded that two missiles had been fired at the plane.)

Related: A guide to navigating the Trump-Iran story

Verifying the video fell to a team of Times reporters that included Malachy Browne, a senior story producer on the Visual Investigations desk. Browne applies investigative techniques to visual evidence, in order to present what his team calls “a definitive account of the news.” Previous reporting by Browne’s team—which currently includes six reporters as well as experts in video editing and motion graphics used to manipulate footage —revealed efforts by Syria and Russia to spin the April 2017 chemical-weapons attack in Khan Shaykhun, and implicated security officers working for Turkey president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in a May 2017 attack on protestors in Washington, DC, among other stories.

Browne spoke with CJR about how his team sourced and verified video of the missile strike against Flight 752. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you obtain the missile video?

There are several Telegram channels that were set up to try to figure out what was going on. It’s basically like a WhatsApp group: people can join to share information. This was actually on one of the channels for Parand, which is the town near Tehran’s airport where the airplane lost its signal. And people on Twitter and on Telegram reported hearing a loud explosion near Parand. Christiaan Triebert, who sits two desks down from me, saw this video pop up. It was a day-and-a-half after the plane had been shot down, and it purported to show a missile hitting. You dismiss a lot, but we were able to find the person who posted this. It was filmed by somebody else, and we verified with him.

There were pictures circulating on social media, unverified, of rocket remains people said were found in Parand. We didn’t run with that because we couldn’t verify it. We couldn’t find where those photographs were taken. And the source seemed a little bit dodgy.

How did you verify the video?

We had already been collecting a lot of videos. We had mapped out where the plane came down, where the debris was, all on Google Earth. We had a flight path, its altitude, and all the rest of it from FlightRadar24. We were mapping out potential missile-launch sites in the area.

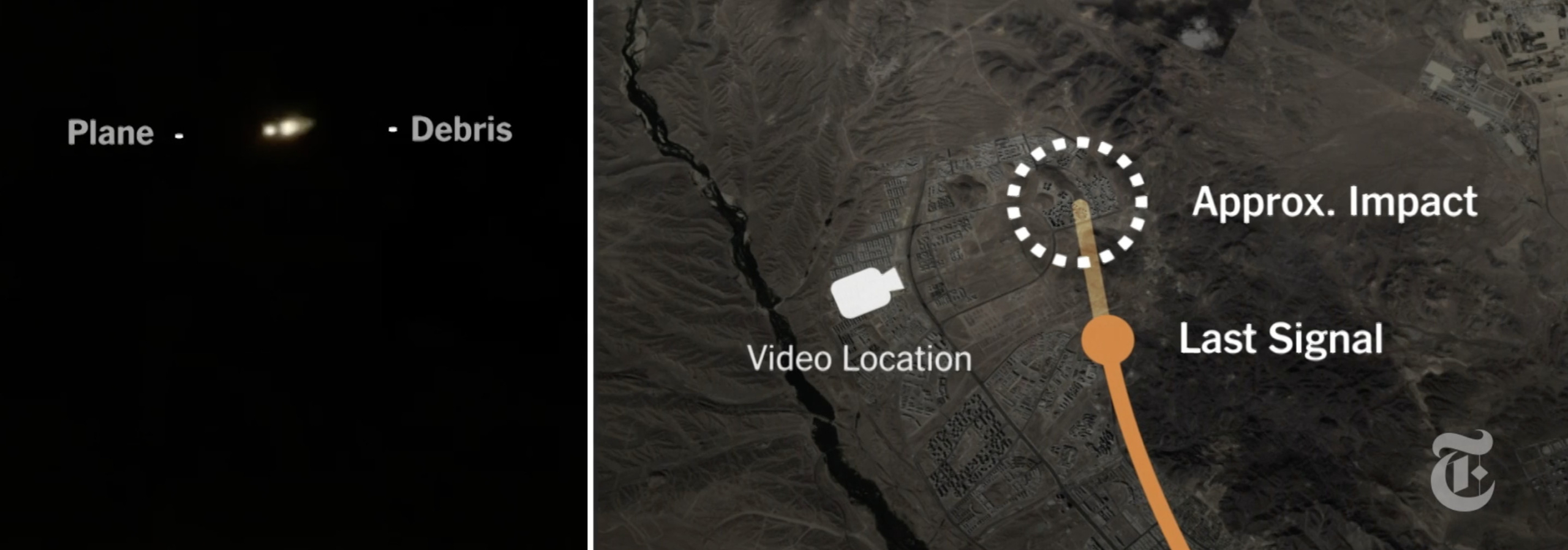

For the geolocation: in the video, you can see a person standing beside what looks like a small cabin. And there’s a little metal tower with sort of cross sections, almost like a ladder, with a light on top. It looks like a security light illuminating the area. And there’s very distinctive rows of buildings that are all identical in the distance. It was the shadow from that lamp post that gave it away. You couldn’t see the lamp post in the satellite imagery, but you could see the shadow right beside that small cabin, and the buildings in the distance. So, we were able to very quickly verify that that video was taken there in Parand. And we are able to identify the corner on which the camera was located very quickly, within minutes.

Not only was it filmed there, but we can see that the plane is flying from the right of the screen, across to the left, and matched up with the path of the plane, basically.

But, because this was such a contentious issue, we still wanted to see if there’s any way that could have been faked. We got our video editors and we slowed it down. We went frame by frame through it. We also looked at the glow of the missile and the moment of the explosion to see if all of that stood up.

Also, there’s the sound. There was a delay from seeing the explosion to the sound reaching the camera. We knew the approximate altitude that the plane was flying at from the flight information. We knew the location from the flight path. So we were able to calculate the distance and the altitude—and, therefore, the hypotenuse between them and the camera—and calculate how long the sound of an explosion would take to travel that distance. And it was roughly what we were seeing and hearing in the video, about 10 or 10.5 seconds.

ICYMI: NPR parts ways with freelancer after Tucker Carlson targets her

What other tools does a visual investigative reporter use?

A lot of this comes down to traditional source cultivation. Our team has been putting out a series of investigations on Syria, on the bombings of hospitals and other civic sites in Syria, primarily by Russian pilots. We have a trove of thousands of pilot recordings, and they’re time-coded. By doing similar types of geolocation, temporal location, establishing the minute that a strike happened or a video was recorded, we’re able to see what pilots are doing in the skies at that time. In a conflict where it’s been very difficult to apportion blame for specific attacks, we’re able to definitively say that this pilot, in this minute, bombed that hospital. Sometimes they are even sharing the coordinates of the hospitals.

We published one in June about an airstrike on a family home in Taliban country in Afghanistan. This poor fellow was working out of the country and got a call from his wife that there was a raid going on. And he says, Okay, I’m coming home right now. He arrives back there and his family is killed and buried. The US was denying they carried it out, and the Afghans were denying they carried it out as well.

We worked with the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in London to get sources in the village who had filmed the aftermath of the attack. My colleagues Christiaan Triebert and John Ismay analyzed the weapons remains that were there. Through our correspondents in DC and our Kabul bureau, we were able to identify that this was a weapon that was only used by the American Air Force in Afghanistan.

It’s just an example of forcing the US military to admit that they had carried out this airstrike. They did not admit to civilian casualties.

Is this kind of reporting attainable for a freelance reporter who is not attached to a news outlet like the Times?

Yes, it is. There’s a terrific collective called Bellingcat, and it’s essentially freelance investigators who do online, open-source investigations, just like we do. One of our team, Christiaan Triebert, worked at Bellingcat before he joined us. There’s also Storyful, where I used to work. There are other groups like the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley. They have a lot of students who do similar investigative work or open-source investigations using satellite imagery, found footage, weapons analysis, and so on. And there’s a really strong online community of people who are sharing skills and information. A lot of them tend to gravitate towards conflict reportage.

ICYMI: While on air, authorities grab journalist and violently drag her on the ground several feet

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.