Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Plenty of journalists can tell you about a story that seemed to take over their lives. But for that story to last seven years, with little promise of an easy resolution? That’s crazy talk.

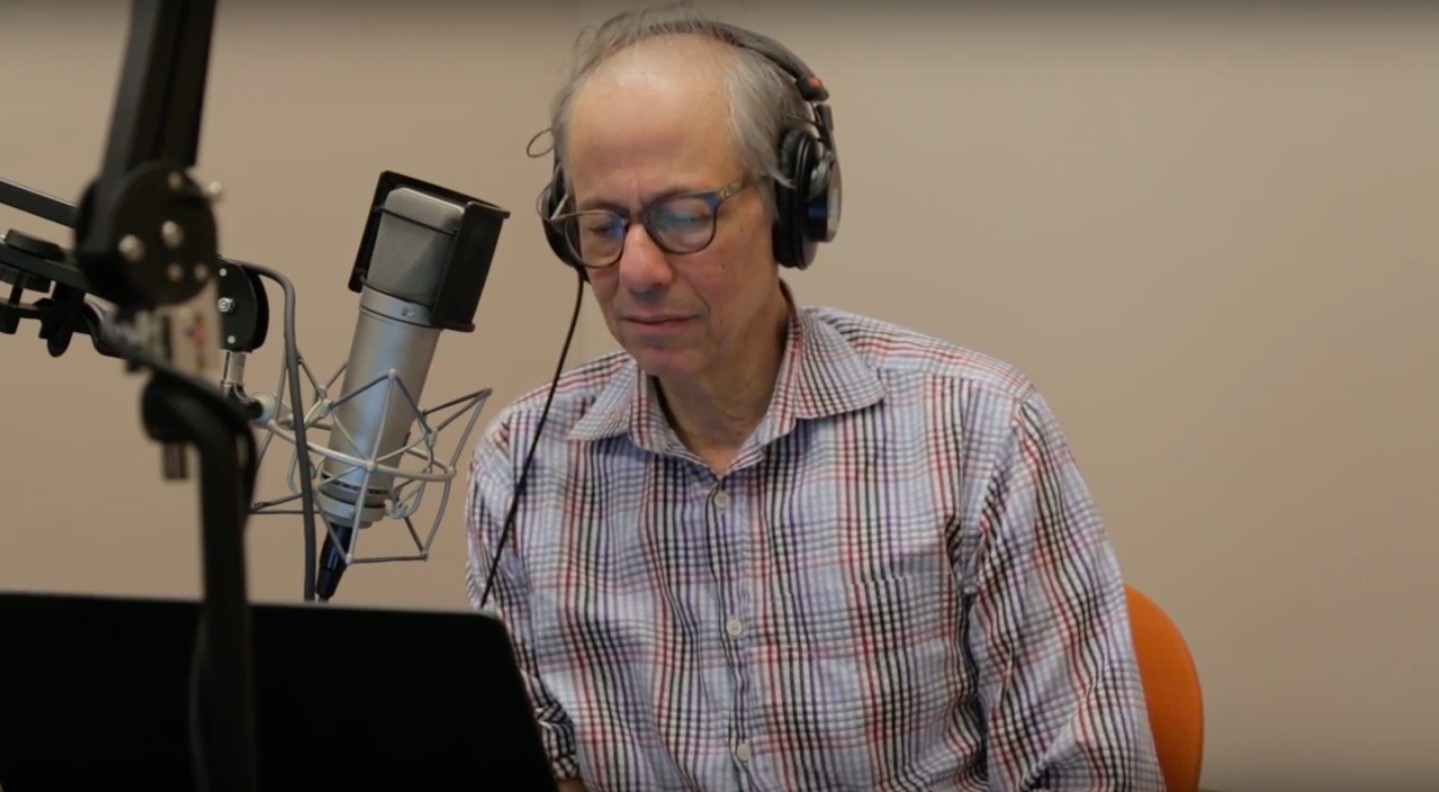

Meet Steve Fishman.

In his new podcast Empire on Blood, the former contributing editor at New York magazine teamed up with the podcast network Panoply to tell the story of Calvin Buari. A former crack dealer from the Bronx, Buari spent 22 years in prison for a double murder for which he has always maintained his innocence.

Trending: Meet the journalism school student who found out she won a Pulitzer in class

Knowing the ending—a quick Google search will tell you Buari was released from prison in 2017 after a New York State Supreme Court judge vacated his sentence—won’t spoil the story. Empire on Blood, a seven-episode series, has an easy appeal for lovers of true crime and shoe-leather reporting sagas, along with a few stops at a house full of elderly tortoises.

But it also is an adventure for anyone interested in the sausage-making of Fishman’s style of by-any-means-necessary investigative journalism. (Disclosure: I worked as an intern at New York magazine in 2014. Fishman was notorious—in a good way—for his habit of asking us to go to great lengths in hunting down hard-to-find information, such as having me call parents on the PTA of a school attended by the children of one of his subjects.) With Empire on Blood, Fishman enters unorthodox reporting territory: He is at times involved in his subject’s campaign, helping him hook up with a new lawyer, and even interviewing the eyewitnesses—for the first time in the case—who would be integral to Buari winning his appeal.

Some stories have a life force, and you find yourself drawn in.

Fishman doesn’t hide himself, his opinions, or his mounting dread as the story takes over his life. The result is arguably a more nuanced, narrative story that, much like Serial, brings the audience into the reporting process, a sort of ride-along. Yet the show never loses sight of the real story: Buari’s fight for freedom—and for the years he lost—in the face of the overwhelming power of the United States justice system.

CJR spoke with Fishman about his decision to start investigating the case way back in 2011, and how he steered his close relationships with the show’s characters, as well as why he says podcasts might be the future of investigative journalism. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me about how you got involved with this story.

What happened is there’s this guy I know who got himself out of prison—got himself exonerated for a murder he didn’t commit. I became friends with him and he said, hey, there’s this guy Calvin Buari, I was in prison with him, I walked the prison yard with him, we worked on our cases together in the prison library. I think he might be innocent. So I told him to have Cal give me a call.

Cal calls, and it’s a funny moment when you get somebody on the phone and you can picture them standing at a prison payphone—you know, with muscle-bound guys lined up behind them saying, hey, hey, your 10 minutes is up. And he’s talking to me and he’s ripping through the evidence of what he says is his innocence, and I couldn’t even follow it.

So I told him to send me the transcripts. And, as you know from the podcast, this 1,100-page thing arrived, and it’s fantastic reading. It’s like a play!

I’m not the kind of journalist who goes out and has six questions that I want to rip your throat out with. I want to understand the story from your point of view, and I want to enter into your world.

The other thing you get in the transcript is info the jury doesn’t get; you get to go into the chambers with the judge and the lawyers. There’s a lead witness against Cal who is his former partner and protégé, who really idolizes Cal, a guy named Dwight [Robinson]. And Dwight turns against him and decides to testify against him for the state, and essentially organizes the entire prosecution. He’s basically deputized. In the transcript, one of the witnesses for the prosecution testified that Dwight had brought him to the police station in the police cruiser with the detective.

But a lot of it came from my interviews with the prosecutor, this guy I call Turtle Man because he just has turtles running free in his house. He said that without Dwight, they wouldn’t have had a case. So now you have this guy organizing the prosecution, and he starts bringing in these drug associates, and the DA starts handing out deals. They’re all drug dealers, they could all go to prison, and the prosecutor says, okay, nobody does jail time. I mean, he shows up at the court hearing of one of the guys and tells the judge, he’s helping us. So the way the system worked was eye-opening to me.

At that point I was kind of hooked. Look, at times I just made half steps or quarter steps, but I kept answering his phone calls and kept taking another step.

How did you incorporate this into your life and your other work? Because it sounds like at times it could be fairly consuming.

Actually, at a lot of times I resisted it, because it became pretty clear to me that it was not really good for my career at New York magazine. I mean, I pitched it to [my editor] five different ways, and you know, he could never see a way to get it into the magazine. There were times that he was like, okay, let’s do it, but then the magazine halved its publication schedule and it reduced the size of its feature well. So for me, this was kind of my orphan child fairly early on, and frankly, it made me nauseous to think that I was gonna keep doing it.But also it’s a human drama, and I’m hooked on the story bit by bit, [and] here’s this guy calling me and saying, Steve, I really need you, I need you to do this, I need your help.

I think journalism is an act of empathy…to the extent that you can tell someone’s story from their point of view, even if that point of view maybe isn’t true in all its particulars.

I didn’t always know he was innocent. I really didn’t, probably for the first three years. And then there comes a point where this private investigator invites me on a train ride to see these people who may or may not be eyewitnesses. I funded that myself; the magazine [didn’t] want any part of it. I took a few days to go down there. It’s kind of a skunk work project, something I’m doing off to the side. And it’s taken sometimes too much of my time.

Did that become problematic?

Yeah, it became problematic! I started this file system with one drawer and then it became two drawers, and now it’s like a huge garbage bin and three drawers, which is some kind of metaphor for how it was taking over my life. It was one of those stories that just took more and more of my time. I didn’t manage it very well, and I think it was one of the reasons that in the end I had to make a decision between what I was gonna do: continue to try [to] be a print reporter, or go off and follow stories that I felt were really compelling and that I could find a home for elsewhere.

It was difficult to manage, though. Some stories have a life force, and you find yourself drawn in. And I was not always an active participant, but Cal calls me up and he says, Steve, I need a lawyer; can you connect me to a lawyer? And these guys can’t make phone calls to random lawyers. So I conference somebody in, and then I’m listening on the call and I’m involved in it.

Related: Behind the success of the LA Times‘s hit true-crime thriller

As a journalist, how did you navigate being part of the story?

There were a bunch of times where I’d have to stop and say to Cal, “You know I’m a journalist, Cal, and I’m writing a story about this.” And I was always loyal to the story, but at the same time, there were clearly moments where I helped Cal, and there were moments where I was a participant. One of the things that I think works for the journalism of this, and what works as a podcast, is you really see the scaffolding. You see the relationship, and not just my relationship with Cal. You see my relationship with Dwight, and Jaymo, and the cops—so all these things that are usually behind the scenes, the stories you tell at the bar, they’re much more out there here.

How did Cal’s involvement with drug dealing, and probably with violence, factor into who you approached with the story?

It was hard. Editors looked at the story and said, Wait, a drug dealer who may or may not have committed a murder? And there’s a lot of competition for space in the magazine, so I don’t think that was necessarily helpful to the wider interest in the story.

You seemed to genuinely like your sources. Tell me about how you navigated your relationships with people who were sometimes diametrically opposed to one another?

I think that if I have one strength as a journalist, it’s that I do actually like the people. I’m not the kind of journalist who goes out and has six questions that I want to rip your throat out with. I want to understand the story from your point of view, and I want to enter into your world.

There is that line, and a journalist always crosses that line, especially if you’re in a story for a long run, and if you’re developing relationships with people. And you always develop relationships with people.

I think journalism is an act of empathy, and to the extent that you can tell someone’s story from their point of view, even if that point of view maybe isn’t true in all its particulars, I think that’s a deeper, richer portrayal of the life you’re trying to portray than just checking a box, That was true, that was false.

There’s a really chilling moment for me in the podcast where Dwight—the person who organizes the prosecution, quite frankly—he lies on the stand, and Turtle Man says later that he didn’t know Dwight lied. And I asked Dwight about it, and he said that it was pretty much common knowledge. So I asked if he was surprised that they let him get away with lying under oath and he said, No, I understood the rules of the game, anybody who plays by the rules is gonna lose.

And for me that was just completely chilling.

Your relationship with Cal and Dwight brought to mind Janet Malcolm’s dilemma of getting a source to trust you even if they might not like the results. How did you discuss with them your obligation to tell the story as you saw it?

Janet Malcolm basically says that every journalist is essentially a con man, and the way I handle that is I really do feel that I enter into a relationship in a full-fledged and honest way.

Yeah, I did remind Cal that I’m a journalist. And there were times that Cal would say, “I know you’re a journalist, but you have to be sensitive about my feelings, because this is my last shot.” And that’s a really poignant moment for me. And it’s a really difficult moment, because I think there is that line, and a journalist always crosses that line, especially if you’re in a story for a long run, and if you’re developing relationships with people. And you always develop relationships with people.

I don’t see myself as a con man. I see myself as richly engaged in real relationships, that in the end conflict with one another.

Do they expect that they will be portrayed in the way they think they’re gonna be portrayed? Of course they do. Are they disappointed? Most of the time, they are. But I don’t subscribe to the theory that I’m a con man. And maybe I’m telling myself a story, but I do feel that, in some way, I’m serially monogamous, serially loyal to and open to and connected to the person I’m speaking with. And when I get back to the typewriter or the microphone, yeah, there are a lot of things that need to be sorted out. But I don’t see myself as a con man. I see myself as richly engaged in real relationships, that in the end conflict with one another.

This is your second longform podcast. What draws you to the medium, as opposed to writing a longform print article or a book?

I’ve had the luxury of being in the magazine journalism universe when it was in its heyday, and it could feel proud and good of itself. I was at the center of that world and I had a taste of it, and it was really heady, and I think that world has gone away to a large extent.

Discovering podcasts, for me, has been incredibly liberating. And not just because it’s a second act, which it is, but because the medium itself is so ambitious and optimistic, and it’s adventurous, and I really think it’s the next, best new home for deeply reported journalism.

The intimacy of [podcasts] is so profound, and it’s built in. But also, hearing the other participants, it’s like being in the room when the turtle walks down the stairs, or being with Jaymo, Cal’s old friend who kind of makes fun of the way I look, all of this stuff that would get left on the floor when you were running through a journalistic narrative. So it feels not peripheral; it feels central to the mission of the podcast.

And in terms of the journalism, the scaffolding’s there. All the really tough questions you asked me, you know Am I an advocate, am I betraying somebody, am I an objective journalist? Decide for yourself, because it’s all there. My relationship, how it’s negotiated, how the questions are asked, my tone of voice when I speak to Turtle Man. I’m not carrying Cal’s water. I’m not going back to Turtle Man and saying ,how can you do this? I think it’s all there.

ICYMI: Sean Hannity in the spotlight

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.