Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Andrea Ritchie, a prominent Chicago lawyer who focuses on cases involving police misconduct, has been arguing for years that an important voice is missing in coverage of police violence, racial profiling, and mass incarceration.

Black women and other women of color are among the most visible forces fighting against police violence and pushing for an end to mass incarceration, she says. Yet most of the conversation and news coverage revolves around the experiences of men; specifically, heterosexual men of color.

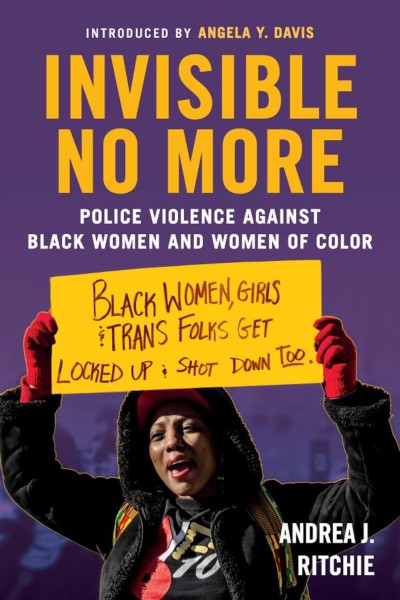

A book called Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color, is her latest project in 20 years of fighting for police accountability and against gendered violence as an attorney, organizer, researcher, and writer. Ritchie, who is black and identifies as a lesbian, says she was a victim of sexual assault as a teen at the hands of a police officer.

Ritchie chatted with CJR about the issues raised in her book, including how journalists frame the public’s perception of the issues, and how they can do better. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

ICYMI: One question that turns courageous journalists into cowards

How does the media help shape the public’s understanding of police violence?

I think media plays a pivotal role in two respects: by reinforcing the silence around experiences of black women and women of color and in breaking it. The mainstream media has reinforced over and over again that police violence is a story about black and brown men who are not queer, who are not trans, and that certainly is an essential part of the story.

I would never dream of saying black and brown men are not disproportionately targeted by state violence. There’s just no question about that, and you will see me in the streets on any given day at protests for Laquan McDonald, or Amadou Diallo back in the day, or Rodney King.

Sandra Bland was definitely heavily on my mind this month on the second anniversary of her death. But somehow her story is not placed in the broader narrative around racial profiling and mass incarceration; it’s somehow almost an anomaly. Like, “let’s read a list of 10 or 12 black and brown men and then we’ll throw in Sandra Bland,” as if it’s an outlier.

Recently video surfaced of a Florida state attorney being profiled and stopped by a police officer, and, again, that wasn’t an anomaly. That was part of everyday experience for black women.

So it’s making that connection to the broader structural issue rather than covering it as a one-off or anomaly?

And making the connection to the stories and experiences of queer and trans people who experience similar things. One of the things I do at the beginning of the book is draw parallels. Eric Garner was subjected to a chokehold in New York City and died again three years ago this month. There are stories of black women in New York City who have been subjected to chokeholds by NYPD. Thankfully, they lived to tell the tale, but those stories need to be tied to Eric Garner, specifically because they happened in the context of broken-windows policing in New York. We need to be making connections to how things are similar for men and women of color and how they are different, and how we can build shared fights and struggles based on those similarities.

What are some of the stories journalists have overlooked?

I think Michelle Cusseaux, for instance. She was a black lesbian who was killed by Phoenix police within a period of days from Mike Brown’s killing. I think that most people don’t know her name, and everyone knows his name. And her case raises questions about how police perceive black women they consider to be gender-nonconforming, or perceived to be queer, and also questions around how police engage the people who they believe to be experiencing mental illness or a mental health crisis.

Tenisha Anderson is also someone who was killed by police within a few months of Mike Brown, but again most people don’t know her name. Most people don’t know Aura Rosser, who was killed by police who were responding to a domestic violence call, and [her death] was within that same six-month period.

Another story that always stayed with me, the first black woman in space, Mae Carol Jemison, after she came back, she was racially profiled and subject to a traffic stop in the town where she lived and worked for NASA and abused by police there in what was a classic driving-while-black situation.

Andrea Ritchie’s book Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color

What are events in the news recently that you can connect with the ideas in your book?

I think that on an ongoing basis, the federal government’s intention or threats to ramp up the war on drugs are very much related. Intensified immigration enforcement at the border and in the interior is very much connected to the ideas in the book. The federal government’s rampant Islamophobia, and how that plays into police interactions. And then there are particular cases. For instance, Charnesia Corley, who was subjected to a public strip search and vaginal cavity search by police officers just outside Houston after a traffic stop for a very minor offense, and they said she was concealing marijuana on her body. I talk about it in the book, and also in a recent New York Times op-ed. This is the way the war on drugs is waged on black women’s bodies, and it’s a pattern that has been in existence since late 80s and early 90s.

RELATED: The telling difference between captions for these Hurricane Katrina photos

There is a lack of diversity in newsrooms, but which journalists are covering these stories well?

I feel like the fact that we’re having much more news coverage of black women and women of colors’ experiences with police violence–you’ll notice who the stories are written by. They are published largely by black women and in some instances white women.

Kirsten West Savali being at The Root means those stories get bigger play. Collier Meyerson being at Fusion and at The Nation means those articles get bigger play. Dani McClain being a Nation Institute fellow means those articles get bigger play.

When I’m talking to black women or women of color reporters, they’re often speaking from their own personal experiences.

Where should journalists look to investigate and find more stories around the experiences of women of color and policing?

If the standard of covering police violence is a fatal encounter, that leaves out police sexual violence, violence against pregnant women, child-welfare enforcement, searches where police officers are conducting completely unconstitutional searches, and profiling of women of color as being engaged in prostitution-related offenses. All of that gets lost if we focus only on fatal shootings of unarmed people.

I think on social media, women of color are telling these stories. I encourage journalists to dig deeper, go beyond what’s at the surface. And follow hashtags like #SayHerName.

When I first started doing this kind of research 20 years ago, I would have to go through reams of Amnesty International testimony to find four or five stories of black women who came forward [as victims of police violence], but nobody lifted those stories up as the iconic ones.

So I would encourage investigative journalists to do that. Go to the civilian complaint review board meetings, because women go to those meetings and talk about stuff that happened to them. Even during the stop-and-frisk hearings that happened in New York in 2013, I would say fully a quarter of the people who testified were young women and old women who talked about their experience of police violence and sexual harassment.

Call up women organizations, anti violence organizations, organizations working with young women, organizations made up of people in the sex trade, or people who are targeted for drug use, because those are the populations being targeted, and you’ll likely find more information about what’s happening.

From archives: ‘Oh, here we go again’: Investigative reporter laid off for the third time

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.