Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

As he made for the exit of the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Courthouse in downtown Manhattan on Thursday, Philip Cohen handed a numbered chip to a clerk and was given back his cellphone, which, like any member of the public, he’d had to surrender on entry. “Who knows what he did while we were in here?” Cohen said.

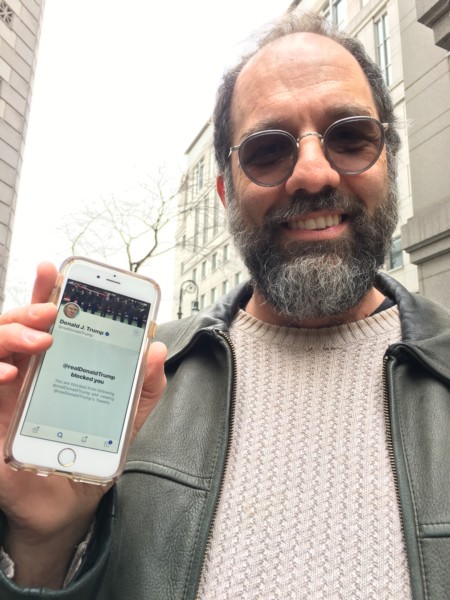

“He” was the man Cohen was in court to challenge: Donald Trump. After Trump tweeted (from his @realDonaldTrump account) about an air traffic control initiative last June, Cohen, a sociology professor at the University of Maryland, replied with a photo of the president and the caption, “Corrupt Incompetent Authoritarian. And then there are the policies. Resist.” Fifteen minutes later, Cohen saw he’d been blocked by the president of the United States.

ICYMI: How 86-year-old Dan Rather became Facebook’s favorite news anchor

“I never thought he would block me. I tweeted at him all the time,” Cohen told CJR outside court. He’d just watched attorneys from the Knight First Amendment Institute tell a federal judge that in blocking Cohen because he didn’t like his tweet, the president had engaged in unconstitutional discrimination based on viewpoint. The Knight Institute, which is based at Columbia University, is representing Cohen and six other plaintiffs—a surgeon, a comic, a musician-activist, two writers, and a police officer—in a bid to qualify Trump’s Twitter as a public forum; part of a broader push to protect the First Amendment from a president who clearly does not respect it.

Neither the First Amendment nor Donald Trump are strangers to the courtrooms of New York’s southern judicial district. It was in downtown Manhattan that judges overturned an obscenity ban on D.H. Lawrence’s racy novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1959, and delivered a first rebuke to the Nixon administration in the Pentagon Papers case in 1971. Trump, for his part, has been called there repeatedly, both as a real estate developer and as head of state. In 1990, he took tough questions on the shady labor deal that cleared the way for Trump Tower. Last year, the watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington sued him (unsuccessfully), citing his ongoing foreign business interests while president.

On Thursday, the two litigious heavyweights came together, squaring off in front of Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald in courtroom 21A. The First Amendment, incarnate in Knight’s Katie Fallow and Jameel Jaffer, argued that because the president uses his @realDonaldTrump account to make official government announcements, it is a de facto public forum—affording constitutional protections to citizens who engage with it. Trump’s government, represented effusively by Michael Baer, responded with its own, dizzying chain of logic: The court can’t tell Trump what to do with his personal Twitter; and even if it could, he’s not using it in an official capacity; and even if he were, Trump’s Twitter channels his own free speech, and thus can’t be considered a public forum.

Judge Buchwald—who, like the United States seal behind her, presided with arrows in one hand, an olive branch in the other, and an eagle eye throughout—looked less than pleased to be told she didn’t have authority over Trump’s Twitter: In one acidic intervention, she asked Baer, “Because the president is above the law? I just wanted to check.” Instead, the bulk of her probing centered on whether or not Trump’s personal Twitter is a forum for public interaction with the government.

Judge Buchwald looked less than pleased to be told she didn’t have authority over Trump’s Twitter.

The debate that followed quickly became a war of analogy. The government argued that Trump uses Twitter as he might behave at a conference—where his entry would invite other attendees to approach him, but where he’d retain the right to ignore people he didn’t want to speak to. The Knight lawyers shot back that this analogy is wrong: By blocking folks on Twitter, Trump doesn’t just ignore them, he bars their access to the conference altogether.

Twitter and other social media platforms are clearly fora for public debate, but courts haven’t yet figured whether the existing rules of speech should apply to them, and if so, how. As Baer argued for the government, “The real-world analogies are a necessary evil in this new context. But I don’t think you can settle this case by analogy alone. Twitter is a series of overlapping conversations happening simultaneously….This is not like the president turning off the microphone [at a town hall].”

Things get particularly messy when these privately owned platforms become vehicles for government speech. As with so much else, Trump has proved deft at exploiting these contradictions. He alternately claims his @realDonaldTrump account is personal and official as it suits him. He’s embraced it, at least implicitly, to circumvent the media and establish a direct channel of communication with voters. But by blocking some users he renders that channel a one-way system.

Buchwald clearly doesn’t do Twitter; when Baer corrected her for referring to retweets as “forwarding on” she looked down and shot back, “You can tell [tweeting] is something I don’t consider it appropriate for judges to engage in.” But her scrutiny of the platform’s technical features—for example, whether the comment thread should be considered as part of, or separately from, Trump’s tweets—was astute. “Trump chose Twitter,” she said toward the close of the hearing. “The question is, is there some significance to him choosing a medium which, by definition, is interactive?” (rather than, say, a blog or press release). While she considers her verdict, Buchwald urged both parties to consider whether it might be a mutually acceptable compromise for Trump to mute, rather than block, accounts he doesn’t like.

It’s true that Philip Cohen and his co-plaintiffs can access information about the government while blocked—including, when they log out, Trump’s tweets. They can also engage with other people’s responses to the president, even if they can’t see the source material directly. But as Cohen pointed out afterward, his ability to amplify his voice on a noisy platform has at least been limited by Trump blocking him. “Once I was blocked [by Trump] a lot fewer people read my tweets,” he said. “My political efficacy is damaged.”

Leaving the courthouse after the hearing, Cohen bounded down the steps for interviews with a bevy of reporters and photographers gathered on Pearl Street. He held his newly returned cellphone up to the cameras, flashing the “blocked” message that still shows when he clicks on Trump’s Twitter page.

As Cohen and the Knight attorneys posed for photos, Moses Padril, a chef, walked past and asked what the commotion was about. “Good,” he replied, when told about the case. “Trump’s Twitter account reminds me of my daughter, and she’s 15. You can’t just say one thing, and then tweet something else.”

ICYMI: Most major outlets have used Russian tweets as sources for partisan opinion: study

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.