Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Popbitch, a UK-based newsletter, makes no attempt to package itself as anything other than what it is: an irreverent, Gawker-style source of “scurrilous gossip” and “scandalous stories” for all who dare to share their email address. A faded photo of Britney Spears holding a photoshopped baby panda awkwardly fills the page. The most recent newsletter muses about the reasons behind the on-again, off-again production of a Freddie Mercury biopic and points out that the UK’s new international development secretary holds the record for saying “cock” the most times in a single speech in the British Commons. So what was a website like this doing publishing a 12,000 word, four-part history of the most infamous American gossip rag of them all, the National Enquirer?

The answer to that, like too many things these days, begins with a global quest to translate the words of Donald Trump—and to predict what he might do next.

ICYMI: The shocking observation a HuffPost editor made about recent sexual harassment stories

Chris Lochery, the staff writer at Popbitch responsible for the sprawling look at the Enquirer, almost surely shatters your assumptions about the type of person who works at a gossip website. When we talked, he was modest, soft-spoken, and wore a plaid button-up and glasses. We discussed his usual coverage areas (everything from the US election and Brexit, to run of the mill who-did-what-with-whom gossip). He frequently referenced mainstream news organizations, including The New Yorker and Wired, as models for the chapter-like structure of his own piece. He seemed a little embarrassed to be taken so seriously.

Lochery’s obsession with the low-brow National Enquirer began earlier this year, as Popbitch experimented with an app-based magazine that would feature stories too long and involved for the weekly newsletter format. Keeping tabs on repeat, “clearly made-up nonsense” (“Dying Cher has three months to live,” for instance) was often fodder for a quick, funny 600-word take. But in June, his study of the tabloid became more serious. Morning Joe hosts Mika Brzezinski and Joe Scarborough had become, like many prominent journalists and news organizations, tangled up in a feud with the newly minted President Trump. Their conflict reached a head in June, when the pair wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post, under the cutting headline “Trump is Not Well.” Senior White House officials, they wrote, had threatened them with a negative story in the National Enquirer and said it could only be avoided with an apology to the president.

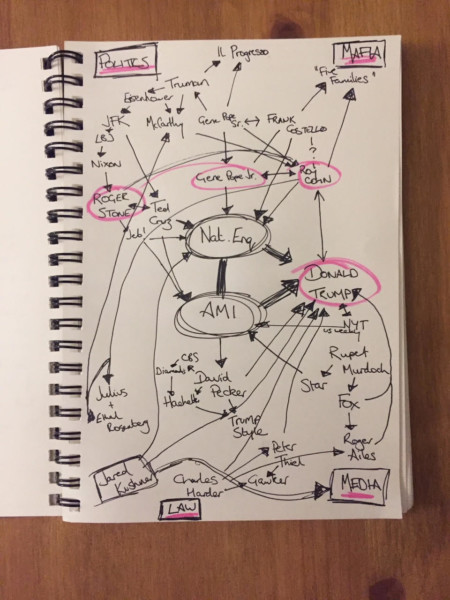

“I thought it was really peculiar how suddenly this magazine had the ear of the president,” Lochery says. He fell into a rabbit hole and spent weeks reading everything he could find on the tabloid: He studied Enquirer covers online (there is a UK version of the tabloid that offers different coverage) and read books about gossip, the foundation of American pop culture. He read histories of the American tabloid industry, one that is tangled up in some of New York City’s most infamous Italian mob circles. He closely followed American reporting on the ubiquitous, but mostly ignored supermarket tabloid. He read a 336-page telling of the tabloid’s inner workings written by its former editor, Iain Calder. Lochery began to notice patterns; the same names kept cropping up, sometimes separated by decades, connecting seemingly disparate events such as an assassination attempt on a famous Italian crime boss and turf wars in New York that helped birth a tabloid boom in the American South, with controversial figures like Roy Cohn, the lawyer who defended Joseph McCarthy. In a notebook, he kept track of these ties on a spider map, charting them out visually. The Enquirer is circled in the center of the page and lines burst out around it like tentacles. Important names are highlighted in pink.

What he found was a surprising history. The National Enquirer was originally called the New York Evening Enquirer. It had been started in 1926 by William Griffin and funded by William Randolph Hearst (yes, that Hearst). In 1952, Gene Pope, a man who Lochery says, it should come as no surprise, was prone to “sensationalist horseshit,” bought the paper with help from his (literal) Italian mob godfather, Frank Costello, head of the infamous Luciano family. At the time, the young Pope had a few other financial backers, among them Cohn, the disgraced lawyer who defended Joseph McCarthy and, a few decades later, when he was probed for alleged racially discriminatory housing practices, Donald Trump. Pope would eventually move the operation to an unassuming town called Lantana in Palm Beach County, Florida, establishing the area as the de facto capital of American tabloid publishing. Lochery kept reading, but the fuss over the Morning Joe debacle quieted down, and he struggled to find a timely peg that would turn his history project into a deep dive that might capture the fleeting interests of readers.

Understanding the history of the big business of American gossip writing—and where Trump fits in—might help readers and mainstream journalists working at “serious news organizations” cover him better.

Meanwhile, in August, Nazis, white supremacists, and members of the so-called “alt-right” rode into Charlottesville. Heather Heyer, a counter-protester, ended up dead, and Lochery, watching from across the pond, saw a nation repulsed by itself. To widespread derision, Trump suggested that there were “very fine people” on both sides, and companies that had continued to do business with him through the racist diatribes and vitriol of the 2016 election finally had enough. They began to divorce Trump by canceling events scheduled to be hosted at the Mar-a-Lago, and Lochery kept tabs on the implosion by reading coverage from The Washington Post’s David Farenthold. The chairwoman of one foundation in particular released a stinging statement. Her name? Lois Pope. Her deceased husband? Gene Pope, the man behind the emblematic, however problematic, tabloid that was one of few American publications to endorse Donald Trump for president in 2016.

Suddenly, Lochery had his news peg.

RELATED: The story BuzzFeed, The New York Times and more didn’t want to publish

He began to monitor the front covers of the Enquirer, now run by American Media Incorporated’s David Pecker. Working with editor and Popbitch founder Camilla Wright, Lochery split his findings into four parts, released over four weeks closely tied to the anniversary of Trump’s election, in 3,000 word chunks. The decision came as a result of frustrations he had reading longform stories from other publications, where he often found himself struggling to stay focused through the often ornery chunks of text.

His goal, he says, was to tie together a multi-decade history of the Enquirer with more contemporary reporting on the Trump administration, ultimately helping readers understand, in one place, how they were connected. Understanding the history of the big business of American gossip writing—and where Trump fits in—might help readers and mainstream journalists working at what he calls “serious news organizations” cover him better.

Trump’s approach is the approach of the gossip. He’s not a reader. He’s always talking about what people have said and what people are talking about. He never talks about what’s been ‘reported.’ You can see very clearly in his vocabulary that he works through whispers.

Writing about Trump has required reporters to exit a world strictly governed by facts and decorum. Lochery says it’s not just that Trump, in between threats of weaponizing libel law, had handed power to a cast of emissaries with a habit of “playing havoc with the truth.” Mainstream newsrooms did not understand the rules of gossip, period.

“His approach is the approach of the gossip. He’s not a reader. He’s always talking about what people have said and what people are talking about. He never talks about what’s been ‘reported.’ You can see very clearly in his vocabulary that he works through whispers,” says Lochery. “So now we’re in a position where no one really gets the mechanism of how Trump communicates and serious news organizations have been scrambling to figure that out.”

A New Yorker piece on the Enquirer describes a conference call on which advisors pitched a story about a viral video showing Melania Trump swatting her husband away as he reached to hold her hand. David Pecker, AMI’s top executive and noted Trump cheerleader, said he hadn’t seen it, which was as good as saying it hadn’t happened—the logic of a gossip.

The public relations machine that governs celebrity headlines now has a major impact on foreign and domestic policy. And as such, publications immersed in this world, Lochery says, are uniquely positioned to interpret Trump—and to write about the so-called whispers he is governed by, free from the rules of on-the-record verification and indisputable proof. The absence of websites like Gawker, which, Lochery says, was especially skilled at drawing on intricate knowledge of pop culture and what he called “frivolous reporting,” is loud.

“The Trump administration doesn’t appear to be treating the job with much nuance. It’s a ‘say it as you see it’ administration. [Newspapers] are used to dealing in nuance. They’re used to dealing in detail. So for them to turn their back on that, they haven’t exercised the right muscles to fight low-down and dirty in the way that the administration seems willing to do,” he says.

So-called coastal elites (a term Lochery hates, and admits that he would likely be lumped into) repeatedly debunk something Trump and his associates say “and congratulate themselves for having understood the finer details,” he says. And they can’t understand why Trump’s base might subscribe to such beliefs as “‘There’s no smoke without fire,’ or ‘he wouldn’t have said it unless there was some truth behind it,’” says Lochery.

I asked Lochery if there was a set of skills gossip writers have that the mainstream media could learn from. He paused, carefully choosing his words.

“There’s a reputational element. You sort of have to sacrifice your place at the table. [Mainstream journalism doesn’t] think of you as being particularly good at your job or worth paying attention to. If you’re writing under the Times masthead, you have a responsibility to not run a story that permanently damages the brand,” says Lochery, referring to the length of time it took major news organizations to properly vet stories like the recent explosion surrounding Hollywood titan Harry Weinstein’s sexual misconduct—whispers that places like Gawker, Popbitch, and others suggested might be indicative of serial behavior years earlier. “If Gawker ran something that had to be retracted, it’s kind of part and parcel of what they did,” he says, acknowledging that major news organizations can’t—and shouldn’t—report things in the same way. Such sites, of course, aren’t required to follow the same ethical and editorial rules mainstream journalists must. Gawker, for example, paid for tips (Popbitch does not). Refusals to abide by the rules of traditional journalism decorum “was eventually their undoing,” says Lochery. But they played a role in the media ecosystem nonetheless, as evidenced by widespread support of the organization as Hulk Hogan destroyed it with help from Peter Thiel.

(It’s also worth mentioning that in 2010, the Pulitzer Prize Board accepted an entry from the National Enquirer for consideration for prizes in both investigative and national reporting after it broke the story on former North Carolina senator and presidential candidate John Edwards’s affair with a campaign staffer. The reporting was, at least initially, ignored by mainstream press.)

It’s well-known that the news media failed to take seriously large swaths of white America during the election. But the Enquirer is a publication that seems to have heard them clearly. The publication uses regular phone polls to survey its readers and test the viability of cover stories, and then bases its editorial content on the results. This method (Lochery likens it to a “critically derided but culturally useful” echo chamber) offers us a peek into how Enquirer readers, many of them members of Trump’s base, feel about the president and a host of other famous people. Scandal after scandal continues to plague Trump, and each time he emerges unscathed, the mainstream media works itself into a tizzy. In the Enquirer, coverage over the last 11 months has remained positive, and Lochery thinks this is a reflection not just of Pecker’s loyalty to him, but of its readers’ loyalty too.

ICYMI: The most-read stories since Trump’s election win might surprise you

And so the crux of his 12,000-word argument is this: A shift in Enquirer coverage of Trump might signal a shift in the opinions of his base. The tabloid offers us a useful, if unofficial, barometer of public opinions about Trump and others we have demonstrated we do not understand.

“Hillary Clinton didn’t lose Florida to Trump because the National Enquirer had spent the campaign calling her a rape-enabling serial killer with Parkinson’s Disease,” Lochery writes. “She lost Florida because a lot of people have never really liked Hillary Clinton—not even the first time around. Which is why the Enquirer (and other AMI titles) have revelled in printing shit and calling her names for 20 years.”

They have been listening to the people we often don’t.

But Lochery and others have begun to notice subtle changes in the way the Enquirer is covering Trump. As of October 29, Trump, who had been featured on 70 percent of Enquirer covers since January, hadn’t made an appearance since late August, as pointed out by Dan Murphy on Twitter. Lochery points out that the Enquirer ran a negative story about former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort shortly after he was indicted as part of a federal investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. Why was the Enquirer, which is said to reflect the opinions of its readers, picking on a Trump loyalist?

Lochery won’t say for certain whether Trump’s base is beginning to turn on its leader—and he is careful to repeatedly point out that he’s not suggesting we, in an effort to learn how to better report on the gossip-in-chief, rush to add cover-to-cover reads of the mostly ridiculous Enquirer to our media diets. But if the tide on Trump begins to turn, he believes we’ll find at least some evidence of that in the pages of the Enquirer.

“[Journalists] were wondering how to reach this sort of unknown America that they suddenly came face to face with. And it’s been there all along,” he says. “The signs are there within the culture if you know where to look for them.”

Image by A.Davey via Flickr.

ICYMI: Former NYTimes journalists are ticked off by new Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks movie

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.