Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

It was almost midnight on November 4, in downtown Detroit. Polling stations would open in just a few hours. Some 60 percent of Michigan’s votes had already been cast or mailed in—but it was a key battleground state, with polls too close, and fluctuating too greatly, to feel certain about. In the final hours of campaigning, J.D. Vance and Tim Walz both swooped in.

Walz’s stop was a quick stump speech at Hart Plaza, on the Detroit riverfront—so quick, in fact, that he couldn’t wait for the Detroit Youth Choir to perform before he took the stage. The crowd gave him a roar of applause. When he was done, they started going home. Then the choir went ahead—an all-Black ensemble, formed twenty-five years ago, featuring singers aged eight to eighteen, some escaping family and neighborhood challenges. They performed to an emptying square. I was the only photographer to stick around. But I was glad I did—I sensed that their predicament was a metaphor for the last months of the election cycle, and of covering it as a photojournalist: you have to wait until the end to see what happens, in order to witness the whole show, because often the reality is both more complex and less certain than the promise.

The same day, at the Capitol Theater, in Flint, Carol Opalewski, an unemployed twenty-five-year-old single mother of a two-month-old son, drove half an hour from her home, in Mount Morris, to see Vance. She said that she was voting for Donald Trump. She loved the event. “Republicans are just-the-facts,” she told me. “They don’t have to have famous people show up, like Beyoncé.”

Twenty-four hours later, Trump won Michigan, and the presidency. Today, he is being sworn in. As a photographer, I’ve wondered lately about the role that images have played in his unusual path in, out, and back into the White House—and I’ve turned to a few colleagues to hear their thoughts about how we see the story.

Todd Heisler has been a staff photographer at the New York Times since 2006 and before that for Denver’s now-defunct Rocky Mountain News, winning Pulitzers at both papers. He has covered seven presidential elections and nine conventions. “Rhetoric in any campaign season can feel abstract,” he told me, “but photojournalists are on the front lines of everything. We can’t do our jobs without being there in front of people, connecting and humanizing bigger issues.”

Heisler spent most of the 2024 election season off the campaign bus—“doing a lot around the influx of migrants in New York City,” he said. “And I’ve always looked at immigration issues north of the border and how they affect various communities.” But in August, he went to Chicago to see Kamala Harris accept the Democratic nomination. “In any convention, they’re obviously scripted,” he said. “There are moments of authenticity that come up, and that’s what you’re trying to find.” He got a shot of her great-niece Amara Ajagu, framed by her braids from behind, watching Harris onstage. “It was visceral,” he recalled. “I knew—okay, this works. I like this frame.”

Sending the image to his editor posed a challenge: at crowded conventions, cellphone and Wi-Fi networks can become overwhelmed. As a work-around, technicians install temporary Ethernet cables around a venue for photographers to connect their cameras directly to servers that editors sitting backstage, or thousands of miles away, can access immediately. “They moved the buffer back,” Heisler recalled. “So my cable did not reach exactly where I was. I had to photograph and crawl through a crowd to get as close as I could to the cable, plug it in, and then go back and forth.” Finally, the editor sent him a text, saying he liked the photograph. Then Heisler went back to work.

It wasn’t until one in the morning, when he arrived in his hotel room, that he realized the image had started to go viral. CNN called it a photo that captured what Harris’s nomination meant for young girls. Michael Shaw, of the photojournalism analysis site Reading the Pictures, wrote that “the photo distills the essence of four days of expressed values and aspirations into a single generational moment and represents a masterclass in visual perception.” The Times’ Instagram post of it garnered more than three hundred thousand likes. “Isn’t that what we’re always working toward,” Heisler said, “to try to make an image that makes people pay attention? When it really happens, it’s amazing that so many people can connect to one of your images.”

Heisler’s photograph did what posed imagery strives for but cannot achieve: the communication of a positive message stamped with the imprimatur of authenticity. The Harris campaign, I’m sure, was thrilled with the photograph, and might have wished they’d gotten it themselves. But if they had, it would have been criticized—correctly—as phony.

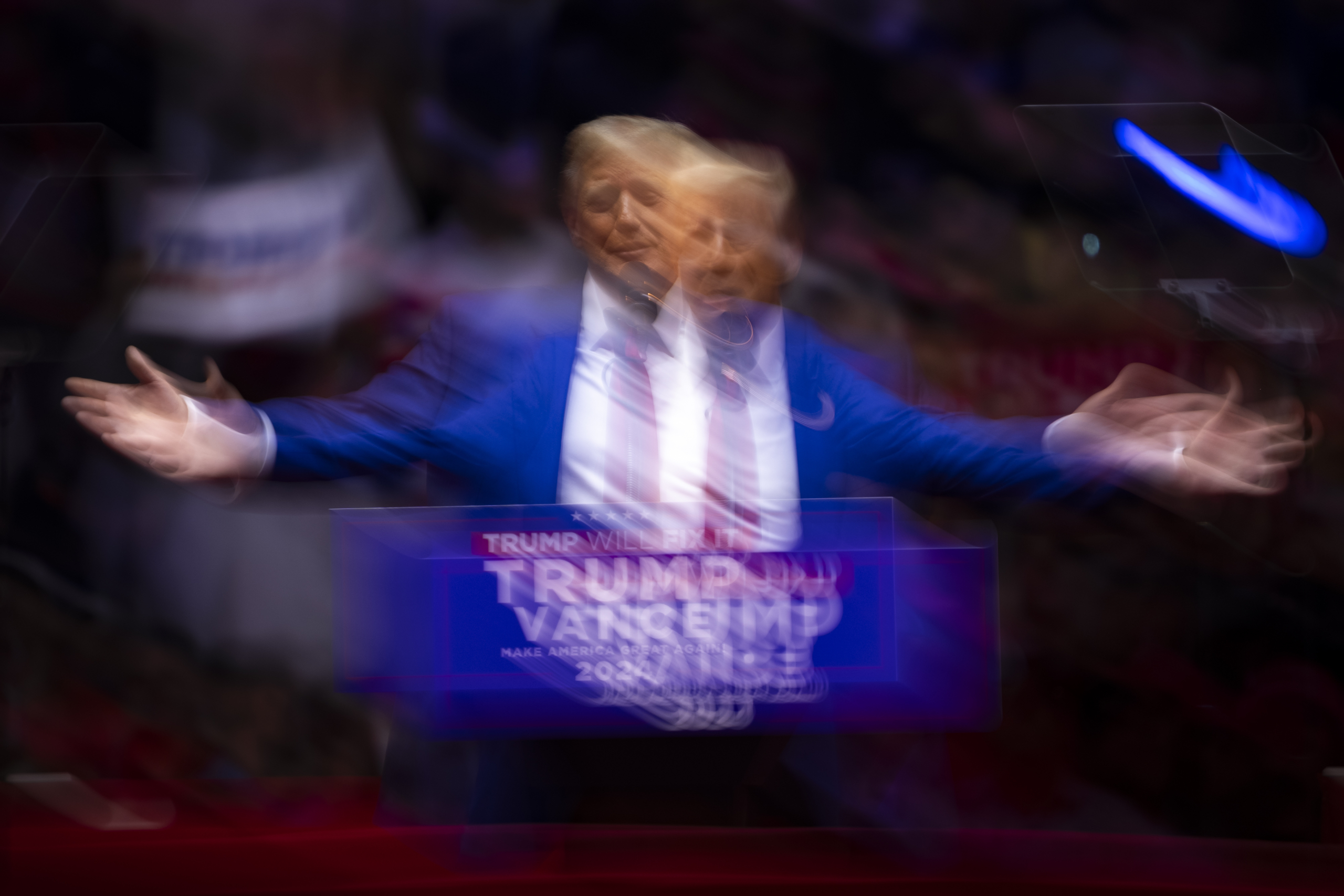

Angelina Katsanis depicted an opposite emotional extreme. She graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2023, and has since started her career with internships at Minneapolis’s Star Tribune and Politico. “My background is not in political journalism,” she told me. “It’s more in storytelling and in local news.” In October, she ventured to New York to catch the Trump event at Madison Square Garden. Then she started hearing talk that it was similar to a Nazi rally in the same setting, circa 1939. “This rally was chaotic,” she observed. “Trump was rambling. His speech lasted multiple hours and went off in all sorts of different tangents.”

At the scene, she decided to try what felt like a fitting technique: she dragged her shutter. “I have my shutter speed at a very low speed so that it’s capturing light for a long period of time, and it captures the movement at the beginning of when I start taking the photo and what’s happening at the end,” she said. “Trump changed his expression over the course of me taking this photo, and I ended up filing it. It’s kind of like tragedy and comedy faces, like a Greek theater mask vibe. I’d like to think that other people saw this as well.” Maybe it was luck, she suggested, “and I can ascribe the meaning to it after the fact, when I’m in the editing phase.”

Weeks later, on election night, Politico sent Katsanis to Harris’s watch party, at Howard University. The images ended up not running—because, she said, “if you get really good, positive photos of the team that loses and really negative photos of the team that wins, you know, it doesn’t matter how good the picture is.” Even so, she told me, “I wish we didn’t so quickly overlook the fact that there was a lot of joy.” She posted the images instead on her personal Instagram account.

David Butow has worked in dozens of countries, covering conflicts including the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and spending years photographing global Buddhism. Lately, he’s become interested in Trumpian politics; his 2021 book, Brink, covered the first term. He was expecting, after the election, to see chaos. Time asked him to go to Florida to capture whatever unfolded.

The Trump team’s press guidelines allowed photographers to shoot from a hundred and twenty feet. “Which is pretty damn far, right?” Butow noted. “I knew that I was going to need a long telephoto lens, which I don’t own. So ahead of time, I had rented a five-hundred-millimeter lens. I planned the whole thing out. The night I landed, I went straight to FedEx, picked up my lens, and then went to the hotel.”

Trump and Vance spent the evening of the election at Mar-a-Lago, then joined a large watch party at the Palm Beach Convention Center. “I thought that there was a strong possibility that I was going to be at the losing campaign that night,” Butow said. “I started to think about what kind of pictures might emerge from something like that. If the results came in and it looked like Harris was going to blow things out early, you’d have a deflated room. I’m starting to think about what kind of pictures are going to convey that mood. And then as the night went on, then it became clear that I was going to be with the winning campaign.”

He positioned himself thoughtfully. “There are times when I like to take a chance and try to work from a more unconventional position off to the side to try to get something different—but this wasn’t one of those cases,” he said. “Given the gravity of the event, I needed to play it as safe as possible. So I chose a spot directly in front of the stage.” By around midnight, Butow realized that Trump would declare victory. “There wasn’t going to be any dispute about it,” he recalled thinking. “This could very likely be the cover of the magazine. That’s when I really started to feel pressure.”

Trump emerged onstage from behind a curtain, and walked over to a podium. “Then he stopped, basking in the adulation and the applause for thirty seconds or so,” Butow said. “I fired off several frames as he’s in that moment, just before he starts to speak—and that ended up being the cover picture.”

I asked Butow about the significance of a Time cover in the broad media landscape we exist in now. “The influence of podcasters, social media influencers, people doing their own shows—I think that has really diminished the impact of legacy journalism,” he replied. “But in some ways it was a full-circle moment for me, because this is the kind of thing that got me interested in photojournalism when I was in high school.”

There was another image pivotal to the campaign, of course: the assassination attempt on Trump in July at a rally in Pennsylvania. The pictures of Trump, bloodied by a grazing bullet wound to his ear, pumping his fist in defiance as his Secret Service detail struggled to protect him, immediately became a signature of the election. I’d hoped to speak with a colleague who had photographed that moment. Nobody wanted to talk to me about it. For Axios, Aïda Amer rounded up photographers’ views, writing that some “worried privately in conversations” that “the images from the rally could turn into a kind of ‘photoganda,’ with the Trump campaign using them to further their agenda despite the photographers’ intent of capturing a news event.” She added, “None would comment on the record for fear of losing future work.”

Americans are told almost every four years that the current presidential election is the “most important one of your lifetime.” It’s hard to avoid concluding that the photojournalism covering this past high-stakes cycle—capturing one important moment after another—helped lead to the outcome. But as we enter the second Trump administration, it’s worth considering how we choose the images we shoot and publish. “It seems the American media has forgotten that one of its core duties is to be oppositional to power,” Daniella Zalcman wrote for CJR in November. “Instead of centering what is at stake, we have made Trump the strongman poster child for his own political violence.” How photojournalists cover these next four years will be as critical as the past eight. Because 2028 will once again be the most important election of our lifetimes—and the ways that Americans look at ourselves will continue to be decisive.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.