Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Jimmy Breslin’s book on the impeachment of Richard Nixon begins at the end: in the Federal Courthouse in Washington, DC, where five of the men behind Watergate were standing trial. After a tense wait, the jury reached a verdict, and reporters ran through the empty hallways to secure a place in the courtroom. It was the first day of 1975, four months after the President of the United States had resigned.

The court was called to order, and a clerk prepared to read the verdict. “The five defendants who would have ruled a nation in their way, standing so that a clerk could tell them of their future,” Breslin wrote. Three were proclaimed guilty, among them Nixon’s Chief of Staff, H.R. Haldeman, and his Attorney General, John N. Mitchell. “This type of American ceremony has no richness to it,” Breslin went on. “Dark tragedies are played out in flat, harsh civil-service surroundings.”

But How the Good Guys Finally Won is no tragedy. True, it’s a book about towering, talented, unscrupulous men brought down by an obsession with power. More than that, though, it’s the story of “good guys”—the politicians, lawyers, and reporters who helped topple the President and his men. In this sense, Breslin’s book was very different from the meticulous catalog of wrongdoing that Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein first published in The Washington Post.

Jimmy Breslin argued that in times like these, stories of wrongdoing are by themselves insufficient.

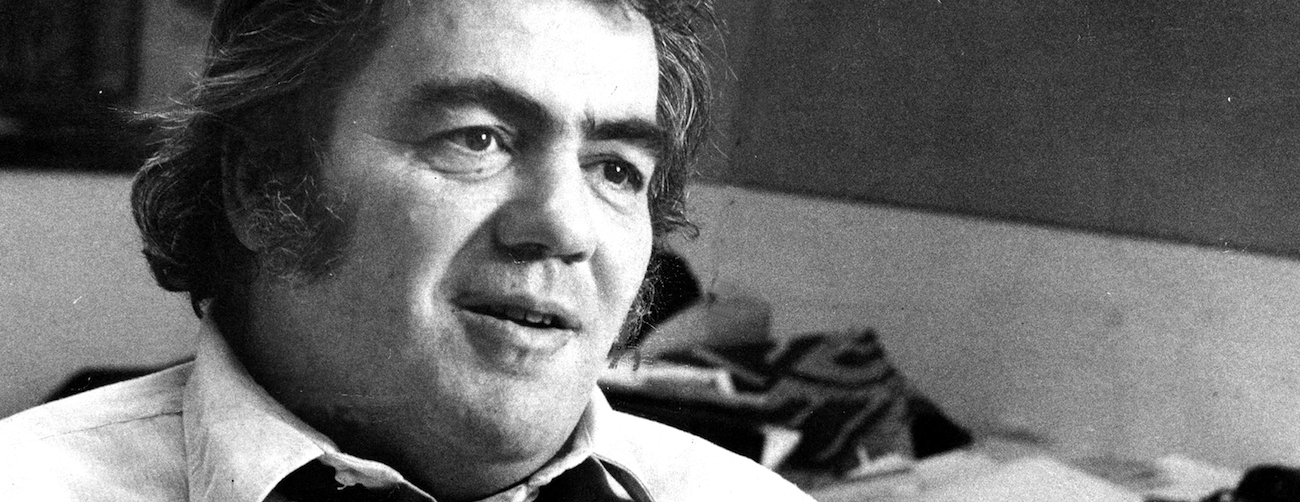

The unexpected optimism in Breslin’s book can be a guide for journalists today. Breslin, who died on Sunday at the age of 88, was writing about a cynical time when corruption crept into the highest offices in the land. In 1974, as the branches of government squared off against one another, pundits worried about a “constitutional crisis.” There are some who fear the same in 2017. Now, as then, journalists find their profession consumed by the dogged search for wrongdoing. Investigations into apparent corruption and alleged collusion have started to climb up the political ladder, though it remains unclear how high they’ll go.

Jimmy Breslin argued that in times like these, stories of wrongdoing are by themselves insufficient. The essential role of investigative journalism in exposing the Watergate scandal can hardly be overstated, and Breslin had little to add to the facts of the case. But his book ran against the grain when it pushed the villains to the margins. “In the end, all convicted criminals are boring,” he wrote. “I don’t want to hear them, or hear much about them again.”

What he said next reads like a call to action for journalists today: “For there were too many decent people, people with honesty and dignity and charm, who were an important part of the summer in 1974 in Washington, the summer in which the nation forced a President to resign from office.” In a time when the loudest voices in Washington must have seemed hoarse from all the shouting, How the Good Guys Finally Won gave voice to a quiet American faith in the institutions of government.

Most of Breslin’s book focuses on Thomas “Tip” O’Neill, a congressman from Cambridge, Massachusetts, who was House Majority Leader at the time. This decision may have been as much the result of good fortune as good journalism: Breslin spent much of 1974 reporting from O’Neill’s office. “He has a large bulbous nose that is quite red,” Breslin wrote. “Large blue eyes sometimes seem to be sleepy-slow and have led a thousand victims into thinking they were on the verge of winning.” O’Neill seems at times an unlikely hero, but in this case, the unlikely hero is easy to like.

Breslin portrayed O’Neill as a master of the political game—a man who understood that, in Breslin’s words, “If people think you have power, then you have power. If people think you have no power, you have no power.” O’Neill knew how to wrangle votes, and relied on others to wage the fight for impeachment in the courts and in the press. He was not a firebrand or a revolutionary. In fact, Breslin saw O’Neill’s role as bureaucratic, in a way. “Somewhere in Washington there was a squealing, grinding sound,” Breslin wrote of the early stages of the impeachment process. “The hugest wheel in the country, bureaucracy, was starting to turn.”

This focus on the human side of bureaucracy may be the book’s most timely insight. How the Good Guys Finally Won suggested that inside the drab and amorphous domain we call the national bureaucracy, there’s an almost endless supply of heroes and villains. Breslin wrote about people, not policies, even in the city where our nation’s policies are made. This will come as no surprise to those who have read Breslin’s newspaper columns, in which his many protagonists included a cop, a gravedigger, an AIDS victim, and a murderer.

Breslin’s book and career serve as a reminder that we write, ultimately, about people.

Under President Trump, of course, journalists must write about policy, and when we see wrongdoing, our obligation is to report it. But Breslin’s book—and his career—serves as a reminder that we write, ultimately, about people. The best defense against accusations of “fake news” may be for readers to see their own lives, their own heroes, reflected in our journalism.

How the Good Guys Finally Won does not always live up to its own ideals. For a book about unsung heroes, it said surprisingly little about the women who helped take down Nixon—for instance, Katharine Graham, publisher of the Post, and Judy Hoback Miller, a key source whom Woodward and Bernstein called “the bookkeeper.” Breslin allowed an odious quote from Meade H. Esposito to introduce Elizabeth Holtzman, who won a seat in the House when it was 97-percent male, and who was central in Nixon’s impeachment hearings. (“And I hear this girl, she’s got all kinds of young girls running around for her. Indians. Freaking squaws,” Esposito apparently told Breslin.) In 1990, a female colleague who was Korean-American accused Breslin of sexism; his racist response earned him a two-week suspension from Newsday.

But perhaps journalists today can succeed where Breslin faltered. As he pointed out, we need optimistic narratives to carry us through a time of pessimism. We need stories not only of crisis and scandal, but also of the quiet, stubborn, sometimes thankless work of civil servants and ordinary citizens. Breslin described those figures well: “People who worked for their country, rather than against it. People who are so much more satisfying to know, and to tell of.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.