Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

During the 2016 US presidential election, Facebook became a battleground of persuasion and disinformation. Since then, there’s been a vigorous public debate about how—and to what extent—social networks are influencing democracy. While these conversations most often focus on the US, there is evidence that misinformation campaigns have sought to sway polls from London to Kinshasa. But does social media affect democracy the same way across the world, or do social platforms have different effects in different nations?

Over the past year, I’ve worked closely with colleagues at Sciences Po and Institut Montaigne in France to explore this question. We spent a year analyzing news stories and social media posts to understand whether French media was experiencing the same breed of political polarization as has emerged in American news and digital media. The good news for France is that they are not coming apart in the same way American media is. The bad news—and the much more interesting finding—is that French media reflects a different and disturbing fissure, between elite media—a small set of media with a strong reputation; we might call papers of record in the US—and non-elite media.

The media in the US is breaking apart from left to right, across the political spectrum, but media in France is breaking from top to bottom.

The research, led by Bruno Patino, Dominique Cardon, Théophile Lenoir, and me, builds on research published by Yochai Benkler and his team at Harvard on the shape of the US media ecosystem during the 2016 presidential election. Benkler and his team found evidence of “asymmetric polarization,” a sharp divide in information universes between the far right and a unified ecosystem connecting the left, center, and center-right. In their analysis, new media like Facebook was far less influential than more conventional online media. In particular, Breitbart—the far-right online publication—dragged Fox News to the anti-immigrant right, and with it, the Republican party. What emerged were two largely independent media spheres, one that revolved around Breitbart and Fox News, seldom encountered by non-Republicans, and one that contained mainstream media, including center-right sources like The Wall Street Journal. For Benkler’s team, what played out on Facebook and Twitter reflected larger, longer-term shifts in the media, notably the emergence of network and cable television that explicitly sought out one political party as its audience.

ICYMI: Audit suggests Google favors a small number of major outlets

We decided to look at the French media in the wake of the 2017 elections. Like the US, France has a mature and complex news ecosystem where social media is becoming increasingly influential. In contrast, France’s politics are ideologically multipolar, not neatly bipartisan. How would these similarities and differences contribute to the shape of the French media ecosystem?

In our analysis of French media, we used the same tools as the Harvard team—primarily the Media Cloud platform. Co-developed by Center for Civic Media at MIT, and the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard, Media Cloud is an open–source platform that captures thousands of articles from traditional and online news sources and analyzes text to see how ideas spread through media. Using Media Cloud Benkler’s team found that a focus on immigration spread from Breitbart to Fox News during the 2016 campaign, and eventually shaped the broader narrative around the election.

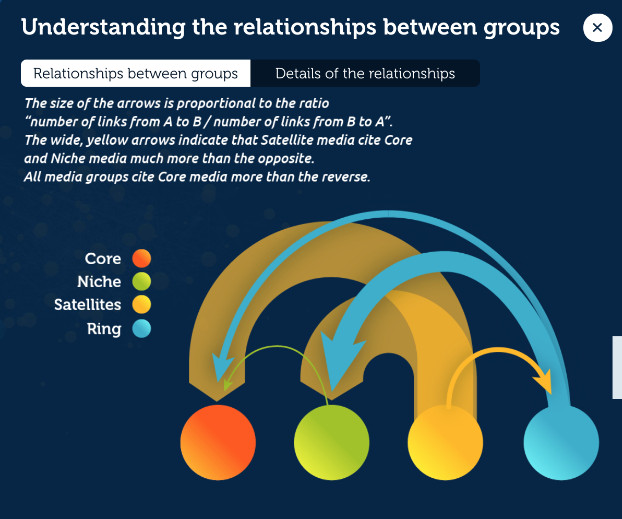

We expected to see something similar in France, as anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant content appears to be on the rise. Instead, after analyzing 18 million tweets and 65,000 articles published between March 2018 and February 2019, we discovered French media is structurally different than US media. There’s a well-connected “core” of elite media in France—older, well-established, and print publications, including Le Monde, Libération, Le Figaro, Les Echos, L’Obs—that sets the agenda for the rest of the media ecosystem. The left and right voices in elite media link to each other frequently, but those core outlets don’t often link to peripheral, online-only media, regional media, or to a rapidly growing “conspiratorial” media space that includes content resembling Infowars and other fringe sites in the US. In France, the core media still act as gatekeepers, determining the shape of the national conversation.

There are great strengths to this gatekeeping model. During the 2017 election, more than 20,000 emails related to Emmanuel Macron’s campaign were dumped online two days before the vote, just before a mandated media blackout around the election. In the US, leaked emails likely had a significant effect in the 2016 election, as attention to leaked emails from Hillary Clinton campaign chair John Podesta drew much of the media’s attention away from the Access Hollywood tape showing Trump making misogynistic comments. But core French news outlets elected to ignore #MacronLeaks, despite online campaigns from WikiLeaks and others to promote the data dump. Most media outlets followed the lead of the core, and the email leak had little effect on Macron’s election.

It’s worth noting that, while they may publish in different spheres, there is overlap. In February, the Daily Beast revealed that members of the Ligue du LOL (League of LOL), an online gang that harasses women, gay men, and ethnic minorities in the news media on Twitter, were journalists in establishment media. The Ligue’s founder, Vincent Glad, was a frequent contributor to Libération; contributors to other elite publications, as well as to France’s editions of Vice and the Huffington Post, have lost their jobs over the cyberbullying.

In the second half of our study, we examined the implications of this elite gatekeeping for the visibility of social movements currently unfolding in France. This led us to the conclusion that the most relevant danger for democracy in French media may be that certain media outlets are so used to setting the agenda that they miss important stories that are emerging far from traditional centers of power. The gilets jaunes (yellow vest) movement, a set of populist protests against fuel taxes and economic hardship, were covered in regional, international, and online-only media from their inception in mid-November 2018, but invisible in the core of French media. It wasn’t until December 1, when protesters vandalized the Arc de Triomphe, that they captured the attention of the Paris-focused elite media.

As the gilets jaunes have emerged as a defining force in Macron’s presidency, their coverage has differed sharply between sectors of the media. The core media outlets have focused on the consequences of the movement for Macron’s government, for other political parties and for the police, while media on the periphery have prioritized coverage of the demands made by the movement and the values of movement participants. A split is becoming clear: While elite media focuses heavily on politics “as it should be,” on existing leaders and political parties, media on the periphery is more participatory, more responsive to popular rhetoric, and better able to see a populist movement like gilets jaunes.

We began our study worried about fake news and polarization in French media and found ourselves impressed with how effective a bulwark against these forces France’s elite media has proven to be. We came away worried, instead, that this elite media may be calcifying, and may not be watching the landscape of French democracy closely enough to understand new, populist forces at work. We hope our research serves as a wake-up call for French media, which need to find a balance between walling out disinformation and unwisely excluding popular anger and outrage. I hope the work also serves as a reminder that, while many social media platforms are run from Silicon Valley, their impacts and effects are always subject to local realities.

Misinformation spread on WhatsApp can have different effects in Sri Lanka and Myanmar than it does in the US, with dramatic and violent consequences. The partisan polarization that characterizes the US in 2019 is not a good description of what’s happening in France. Not only do we need to do the hard work of understanding how social and news media affect democracies, we need to do that work around the world, keeping ourselves open to the very real possibility that these effects are local, not universal.

Our study, published by Institut Montaigne, is available online, in English here. We are planning a longer technical paper looking in more detail at research methods later in 2019. I am also co-creator of Media Cloud, an open-source software from Github. Free accounts to use the tool—in English, French or a dozen other languages—are available at mediacloud.org.

ICYMI: I wrote a story that became a legend. Then I discovered it wasn’t true.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.