Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

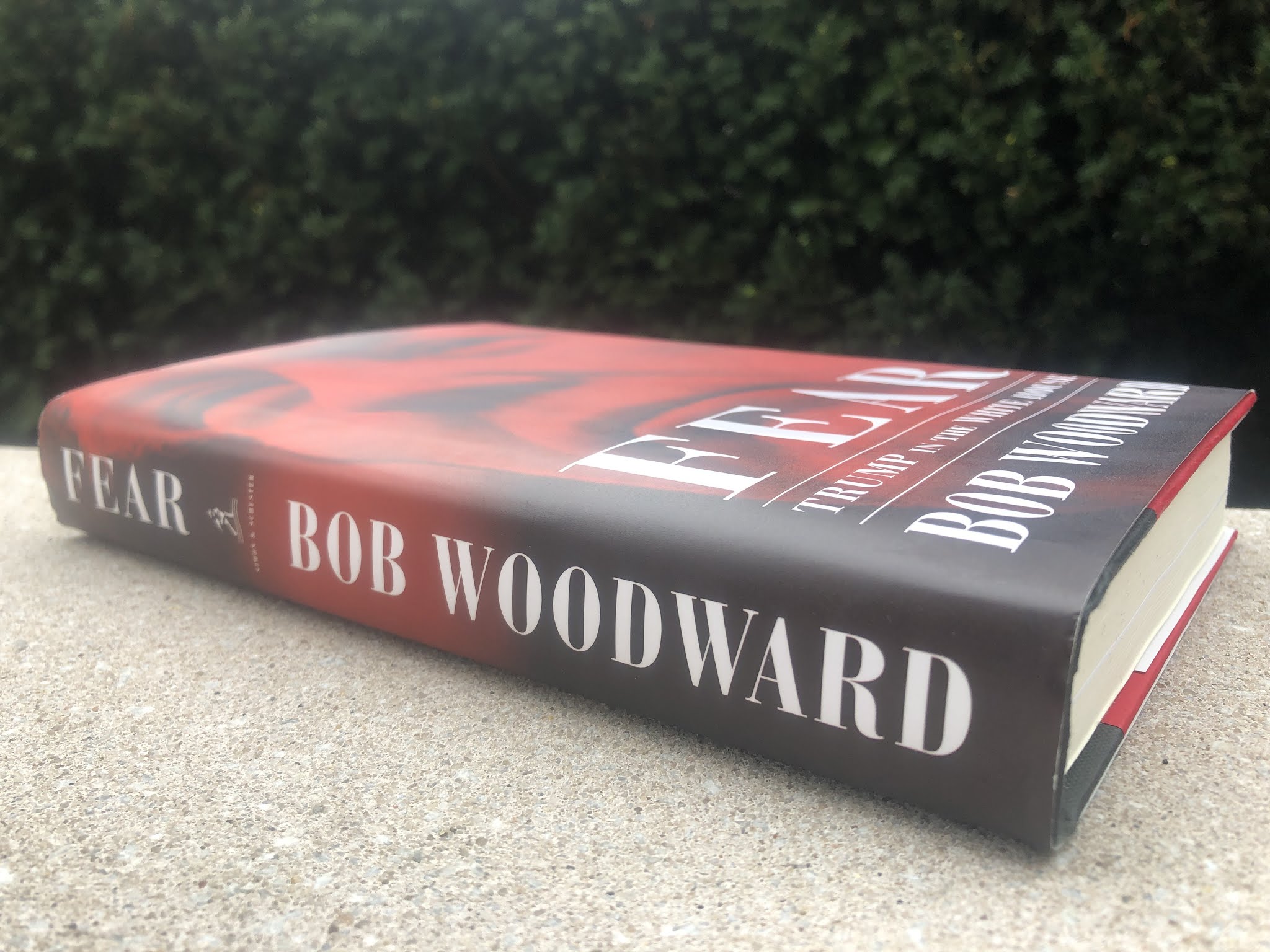

Bob Woodward’s new book, Fear, a devastating portrait of a presidency lurching from crisis to crisis, is a certified blockbuster. On its first day on shelves, 750,000 copies were sold. The hype was good: for more than a week before its debut, Fear dominated the news cycle, as journalists and pundits parsed the revelations within. Those scoops, as Woodward writes in his note to readers, come from hundreds of hours of interviews conducted on “deep background,” meaning that the officials with whom Woodward spoke are not named in the text.

This sort of reporting isn’t new for Woodward, nor is he its only practitioner. In books about presidents from Nixon to Obama, Woodward has employed a similar approach, conducting exhaustive interviews on background and using the information he gathers to write from an omniscient perspective. Woodward and Carl Bernstein, his colleague at The Washington Post, used the most famous anonymous source in American history—FBI Associate Director Mark Felt a.k.a. “Deep Throat”—to expose the cover-up behind the Watergate burglary that unraveled Nixon’s presidency. This week, Woodward told Michael Schmidt of The New York Times that “you won’t get the straight story from someone if you do it on the record. You will get a press release version of events.” But as Axios’s Jonathan Swan, one of the current masters of Washington intrigue, noted, sources “also lie on background. A lot.”

ICYMI: 11 images that show how the Trump administration is failing at photography

And no group of officials in recent memory has proved as willing to bend the truth as those in the Trump administration. The recent controversy over Steve Bannon’s invitation (later rescinded) to appear at The New Yorker Festival led The Washington Post’s Margaret Sullivan to declare, “Enough, already, with anything Steve Bannon has to say.” When Kellyanne Conway appears on CNN, critics question why the network gives a platform to the official who coined “alternative facts.” Yet for Woodward, reliance on the same sources is received differently: If it’s not OK for David Remnick to talk to Bannon in front of an audience, why is it OK for Woodward to use him, quite obviously, as a key source in the book?

Woodward’s approach hasn’t changed; the climate in which his sources are viewed has. Every administration is filled with people who have an agenda, who want to spin events in their favor, but the lines of credibility have shifted. In taking on the Trump presidency as his topic, Woodward is left to assemble a reliable book from unreliable sources.

In taking on the Trump presidency as his topic, Woodward is left to assemble a reliable book from unreliable sources.

No one—with the possible exception of a few people in the White House—doubts that Woodward’s sources are real, or that he has exhaustive tapes of their conversations. (He’s publicly released one, of an interview with Trump he conducted after the book was complete.) When possible, as in the case of a January 2018 National Security Council meeting, Woodward clearly draws on multiple sources. He writes that, after Defense Secretary Jim Mattis told Trump that the US presence in South Korea was designed to prevent World War III from breaking out, “Time stopped for more than one in attendance.”

But because Woodward’s omniscient style doesn’t attribute the events to specific sources, it can be difficult to know whose version of the truth readers are getting. Every subject, of course, brings his biases to an interview, and can only provide his perspective and recollection of events. In Fear, a small handful of sources dominates large chunks of the narrative, and in some cases—where one can discern who is driving the story—that raises concerns about whether readers are getting a true picture.

Woodward hasn’t confirmed the identities of any people he spoke with, but it doesn’t take much of a close reading of Fear to recognize the fingerprints of Bannon, Rob Porter, John Dowd, and Reince Priebus, among others, on the narrative. Bannon is a visionary (see ch. 2), Porter a bulwark against chaos (ch. 32), Priebus a beleaguered good soldier (ch. 18), and Dowd a committed lawyer who knows his client is “a fucking liar” (ch. 42).

Early chapters covering Trump’s campaign are often given over to Bannon’s view. He feels sorry for Paul Manafort; he judges Manafort’s wife to look younger than she is; he wants to call Chris Christie a “fat fuck.” Bannon, in Woodward’s retelling, is responsible for closing the gap between Trump and Hillary Clinton and developing a strategy that leads to the most shocking result in modern electoral history.

Porter, a central figure throughout much of the book, is cast as an “honest broker” trying to negotiate between warring factions and depicted as one of the staffers who works to keep the “nervous breakdown of executive power” from doing more damage. His resignation, in February 2018, amid allegations of domestic abuse backed up by photographic evidence, is given little attention; the brief section in which it’s mentioned concludes with Gary Cohn, who was director of the National Economic Council, thinking that “one of the main restraining influences on Trump was now gone.”

Dowd, who from June 2017 to March 2018 was Trump’s lead lawyer for the special counsel investigation, struggles to keep the president clear of Robert Mueller’s tentacles, all the while recognizing that Trump is unable to stick to the truth. Readers are privy to Dowd’s thoughts, such as when he observes that “the president was very lonely,” presumably because Dowd shared them with Woodward. He’s shown battling with Mueller and his associates, trying to protect the president, before he resigns.

The reliance on Bannon for sections of the narrative is especially troubling. Practiced in the art of self-aggrandizement, he not only holds the sort of views on immigration and race that got him banished from The New Yorker event, but he’s told his story before.

Woodward has earned readers’ trust through a career built upon diligent reporting, and it’s that record that led even Trump to admit, on their taped conversation, that “You’ve always been fair.” Indeed, Woodward gets at a central truth of the administration, but at least some of the sources he draws from have proven that they have, at best, a loose relationship with honesty. Relying on their words to narrate events, to borrow the title of Joshua Green’s book on Steve Bannon, is a devil’s bargain.

RELATED: As an industry rots, Michael Wolff laughs his way to the bank

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.