Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Bill Nemitz remembers the moment he realized a new front had been opened in one of the most important senate races in the country. It was early October; Nemitz, a columnist for the Portland Press Herald, had his home television muted during a commercial break when he saw a familiar face appear on screen. It had been almost a year since Bill Green, a legendary Maine journalist, had retired, and Nemitz figured the presence of the charismatic, folksy former host of a long-running feature program might signal some sort of anniversary special. He turned on the volume, “and then—boom—he’s talking about politics,” Nemitz says. “It was a head-turning moment, no question. It was almost like someone you’d know for decades starts speaking in a different language.”

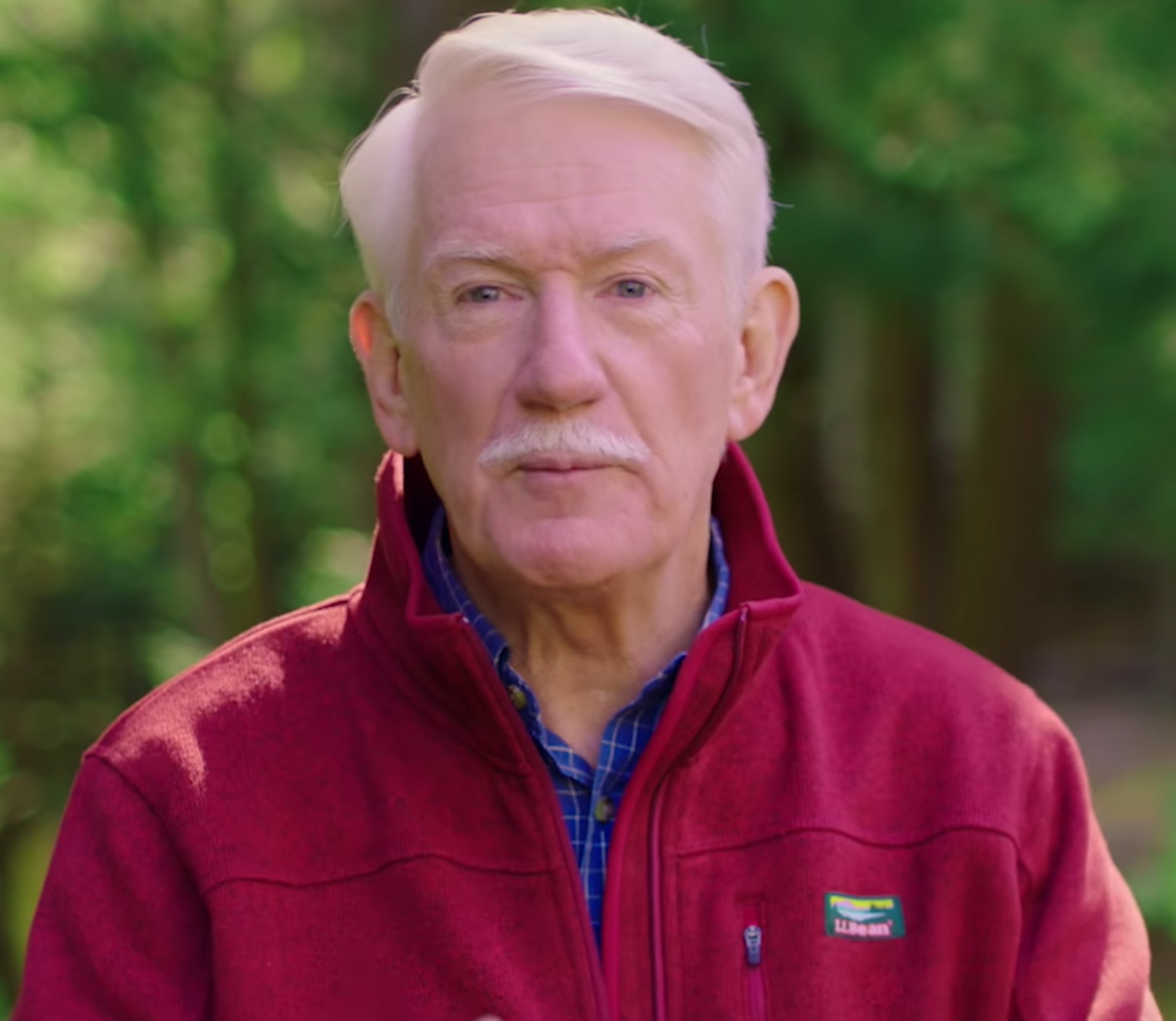

For nearly fifty years, Bill Green was a fixture of news broadcasts in Maine. After two decades as a sports reporter, he became primarily known for his feature program that focused on the outdoors, and concluded with Green’s reminder to viewers, “Don’t go bragging just ’cause you’re from Maine.” Green’s decades on the air as an apolitical cheerleader for the state and its people engendered a sense of familiarity and trust among Mainers. Now, he had picked a side.

Wearing an L.L. Bean fleece pullover and his trademark white mustache, Green mimicked the attack ads that had blanketed the airwaves for months. “Did you know that Susan Collins hates dogs?” he asked with mock incredulity. Implicitly acknowledging Donald Trump’s unpopularity in the state, Green went on to argue that “no matter who you’re voting for for president, Susan Collins has never been more important to Maine.” Soon, the ads featuring Green supporting Maine’s incumbent senator were everywhere, popping up during breaks in local news and NFL games. They got the attention of Mainers across the state, from journalists to Stephen King. Green’s former employer, the local NBC affiliate, even had to make clear that the former journalist did not speak for the station.

Bill Green is a true Maine legend, and his support means the world to me. #mepolitics pic.twitter.com/aQ6P6Gx1cu

— Susan Collins for Senator (@SenSusanCollins) October 5, 2020

Green, a registered Democrat who describes his own political beliefs as moderate, gave license to Mainers uncomfortable with Trump to split their ticket. His ads highlighted Collins’s Maine roots and focused on the idea that the money supporting Democratic candidate Sara Gideon was “from away,” a serious charge in a state where parochialism matters. In the final weeks of a campaign that polls consistently showed Gideon leading, it may have been enough to swing votes to Collins and keep the Democrats from a vital pick-up in their quest to take the Senate. “Bill Green was the perfect messenger, and he came in at the right time,” Chrisitan Potholm, a professor of government at Bowdoin College and former strategist for numerous state-wide campaigns, says. “He was authentic Maine, and he knew authentic Maine. I think he made the difference in a race in which Gideon started out with a lot of advantages, but Collins only had to do a few things [right].”

Crossing the Rubicon from journalism to political player didn’t come easy to Green. “It was like walking a plank, because I’m not a journalist [anymore],” he says. “I knew I couldn’t go back on Channel 6 after doing that. I knew I couldn’t go back and be a straight journalist.”

Throughout the summer and into the fall, Maine’s airwaves were suffused with ads from both campaigns, along with spots funded by outside groups that turned the contest into one of the most expensive senate races in the country. The Green endorsement, which came with the election just a month away, was born of a personal relationship. Green first met Collins through his sister Julie, who worked with the future senator at Husson University in Bangor during the 1990s. The two women developed a friendship, and Green got to know Collins well over the years. When he ran into the senator at Julie’s retirement party last December, Green told her that if she ever needed his endorsement, he’d be happy to provide it.

By September, Collins did. She had earned sixty-eight percent of the vote in her previous election, and, in 2016, was the second most popular senator in the country, trailing only Vermont’s Bernie Sanders. By the final year of the Trump era, however, Mainers had turned against her. After voting to confirm Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court and opining that Trump had “learned” from his impeachment, Collins’s approval rating was underwater, and she trailed in every 2020 poll on the Real Clear Politics tracker.

Enter Green, who Nemitz, the Press Herald columnist, calls “one of Maine’s preeminent storytellers.” Through his years in broadcast journalism, first as a sportscaster and later as the host of the Saturday evening, outdoors-focused staple Bill Green’s Maine, Green developed an “easygoing, approachable manner that left many people feeling like he was their friend even if they never met him,” Nemitz says.

One of the implicit arguments that the Collins campaign made was that her challenger, who was born in Rhode Island and has lived in Maine for only sixteen years, did not understand the bucolic lifestyle that Mainers outside of the more densely populated southern region of the state practice. Green, who was born in Bangor, never acknowledged Gideon’s roots explicitly, but he allows that some things don’t need to be voiced. “There’s some nuance when a Mainer speaks to a Mainer,” he says. “You can say things without saying them. In the conservation ad, I’m standing wearing a Maine Guides vest that people who hunt and fish would recognize. It means I have some credibility, and they know I have some expertise and love of the outdoors. We don’t mention guns, but in that is a veiled Second Amendment statement.”

WATCH 📺:

Take it from Bill Green: Maine needs Susan Collins. #mepolitics pic.twitter.com/4BNwbhECXb

— Susan Collins for Senator (@SenSusanCollins) October 16, 2020

Even those who opposed Collins’s reelection felt the impact of the ads. “Bill Green has for years been the folksy manifestation of an idealized version of Maine,” Mary Pols, a former reporter for the Press Herald who now works at Bates College, writes in an email. “The kind of Maine where we are so tough and resilient that we lobster at 97 [years old] or do the whole [Appalachian Trail] as a family or run marathons after beating cancer. It’s a warm and fuzzy place where we know best but we don’t boast about it. It is a Maine without heroin addicts or people who drive around in their pickup trucks with the Confederate flag flying behind them.” Pols criticized Collins’s unwillingness to stand up to President Trump and vote in favor of Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court, but admitted that Green’s ads, specifically one which ended with Collins endorsing the message while seated next to her dog, Pepper, were effective. “I felt the magic of that ad even though I believed every word Christine Blasey Ford [said] and do not believe that Brett Kavanaugh should have been seated on the Supreme Court,” she writes.

Despite the positive response from many viewers and the Collins campaign, which came back to shoot additional spots after the success of the first round of ads, Green did not feel confident as he took the stage to introduce the senator at her election night rally in Bangor. “I thought she was beat,” he says. “I thought, ‘You gotta walk across the field and shake hands with the other team,’ and I wanted to be there at the end.” Instead, as the first results began trickling in, Green sensed that perhaps Collins had a chance to pull off the upset. He and his wife, Pam, were invited up to Collins’s suite at the Hilton Garden Inn to watch with the senator as it became clear that not only was she winning, but that she would clear the fifty percent threshold that kept the race from going to an automatic run-off demanded by Maine’s ranked choice voting system. “It was very much like the biggest game that either me or one of my children has ever played in. It was like the state championship game,” Green says of his feelings as he watched the victory unfold. “It was a thrilling night, and it went better than one could imagine.”

Green with Collins (right) on election night. Courtesy of Bill Green.

Not everything about his experience as a political neophyte was perfect. Green says that he’s faced vitriol on Twitter, where he usually confines his commentary to complaining about New England Patriots’ play calls, and has received critical letters at his house. “A lot of the trolls have been asking me how I like helping Mitch McConnell,” Green says. “But I don’t like helping Chuck Schumer either. I don’t like either one of those guys. Neither one of them gives a rat’s patoot about helping Maine.”

Green allows that he would be willing to speak up for Collins again in six years, but doesn’t see himself endorsing anyone else. “I’m retired, and if I want to speak out about something I’m going to speak out on it, but I don’t have any plans to do anything like this again,” he says. “This was perfect in some ways, and it was more than I wanted in others. I just didn’t think it was going to be as big as it got. It’s amazing really, what happened here. I’m not saying my endorsement did it. I think you had to have Susan there, with all the good work she’s done and her likability, but I was glad to play a little role in it.”

NEW AT CJR: Apocalypse Then and Now

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.