Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

In mid-October 2012, President Obama’s reelection campaign was in trouble. He had just turned in a listless debate performance against former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney, and his three-point lead in the polls had evaporated. So anticipation was high for the second debate, a town hall. Another stellar performance by Romney might torpedo Obama’s prospects.

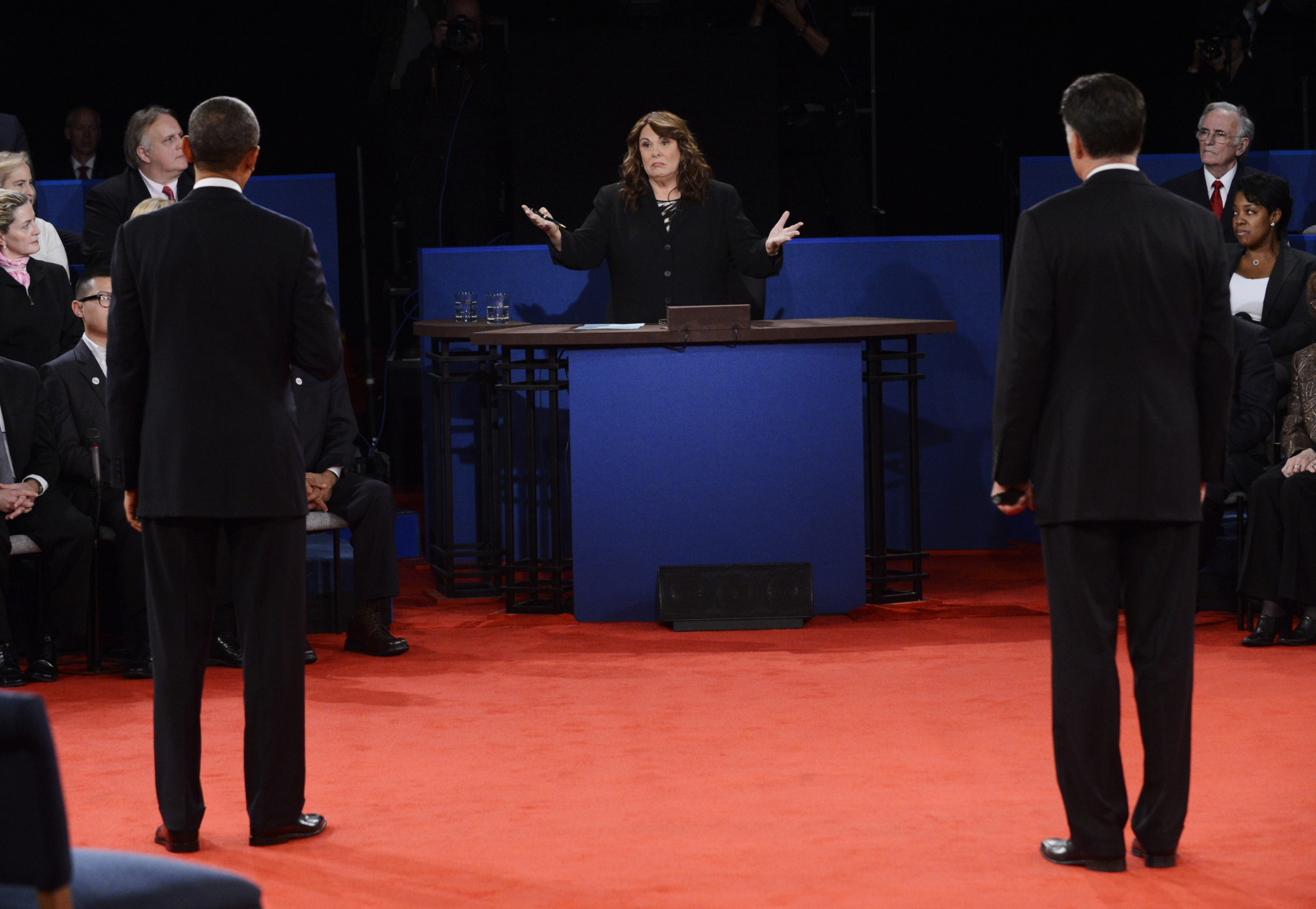

Candy Crowley, a twenty-five-year CNN veteran, was moderating when the discussion turned to the attack in Benghazi, Libya, that killed four Americans, including Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens. Republicans were incensed about Obama’s response, and about his administration’s initial inclination to blame the violence on an anti-Muslim video. Romney told the audience that “it took the president fourteen days before he called the attack in Benghazi an act of terror.” Crowley fact-checked him on the spot, though it was confusing: “He did call it an act of terror.… It did as well take two weeks or so for the whole idea, there being a riot out there about this tape, to come out. You are correct about that.”

The truth was somewhere in the middle; immediately after the killings, Obama said, “No acts of terror will ever shake the resolve of this great nation,” but he wasn’t more specific for many days.

Crowley was quickly savaged by conservative commentators. She “had no business trying to fact-check in real time, because she was incorrect,” fumed Gov. John Sununu, a surrogate for Romney. “Thank you for distorting the truth, Candy Crowley,” harrumphed Fox News’s arbiter of accuracy, Sean Hannity.

Crowley’s follow-up also wasn’t entirely clear. She said shortly after the debate that while Romney “was right in the main, I just think that he picked the wrong word.” (Crowley left the network two years later and could not be reached for comment.)

Fifteen months after the debate, Romney was still sore. “I don’t think it’s the role of the moderator in a debate to insert themselves into the debate and to declare a winner or a loser on a particular point,” he said.

Such semantic issues seem almost quaint today, while we’re battling a global pandemic, an economic crisis, and devastating wildfires. Now journalists need to intervene when the air becomes thick with lies. Which means that they could easily be overwhelmed, starting September 29, when Fox News’s Chris Wallace moderates the first debate between Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

For five years, and particularly in the six months since the covid-19 epidemic began, Trump has been front and center on our screens. Through rallies, speeches, and briefings, he has made himself endlessly available to the press and the public. And when things start to go badly at one of these appearances, Trump has learned to change the mood by calling on a friendly reporter, turning the microphone over to a subordinate, or leaving the stage altogether.

He is up-front about his motives. A few weeks ago, sycophantic One America News personality Chanel Rion asked Trump whether “journalists are afraid they might lose their jobs if they don’t attack you the way they do every day.” The president admitted what he’ll do when a reporter confronts him with a question he doesn’t like: “I’ll say, ‘Thank you very much. Bye-bye.’ And I leave.”

That will change with the debates.

Wallace has already shown he can be tough on Trump; he hasn’t been able to demonstrate that with Biden, since the vice president has ducked his interview requests. But tough questions won’t be enough. The candidates must be confronted when they start lying. That’s going to be a particular issue for Trump, given his casual and halting relationship with the truth.

Wallace will have a lot of latitude, as will NBC’s Kristen Welker, who is moderating an October 22 debate. The Commission on Presidential Debates is allowing them to choose six segments, of fifteen minutes each, on whatever topics they want. After each candidate responds to the question and to each other, “the moderator will use the balance of the time in the segment for a deeper discussion of the topic.” Meanwhile, c-span’s Steve Scully is hosting a town hall on October 15.

So while Wallace, Welker, Scully, and their teams need to prepare tough questions, they also need to be prepared for Trump’s mendacity. They can’t expect one candidate to fact-check the other. And they can’t wait for the post-debate news crews to clean up the mess.

It’s not easy. At a tough town hall Tuesday night, ABC’s George Stephanopoulos did his best to challenge Trump on healthcare, particularly given how often the president renews his bogus “two weeks” promise to provide an Obamacare replacement plan. But because of the format, and because it’s hard to stanch a “firehose of lying,” Trump still flooded the zone with falsehoods.

Given that Wallace and Welker will get a lot of leeway, they’ll need to have Glenn Kessler– or Daniel Dale–quality fact checkers in their control room, providing instantaneous quality control on the candidates’ claims. So armed, moderators can help voters see which candidate is more capable of handling and delivering the truth. And they can do it almost in real time, with more support and more clarity than Crowley could offer in the Obama-Romney debate.

This will be a challenge with Trump, who gets testy when called out on a lie. In a briefing at Trump’s Bedminster, New Jersey, club last month, CBS reporter Paula Reid asked him about one of his most frequent whoppers: “Why do you keep saying that you passed Veterans Choice? It was passed in 2014. But it was a false statement, sir.” Trump listened, ignored the question, and responded, “Okay, thank you very much everybody” as he walked off the dais to applause from his club patrons.

In his OAN interview, Trump made clear that he thinks he should be the one to judge what’s legitimate: “I don’t mind tough questions. What I don’t think is fair are some of these questions that are really statements more than questions. They’re supposed to be asking questions of the president of the United States. And if they can’t do that, then I just do something else.”

For three nights this fall, Trump won’t be able to “do something else.” Let’s hope our journalists, and the fact checkers who support them, are up to that challenge.

NEW AT CJR: Ten questions for the Trump ally who runs US funded media

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.