Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

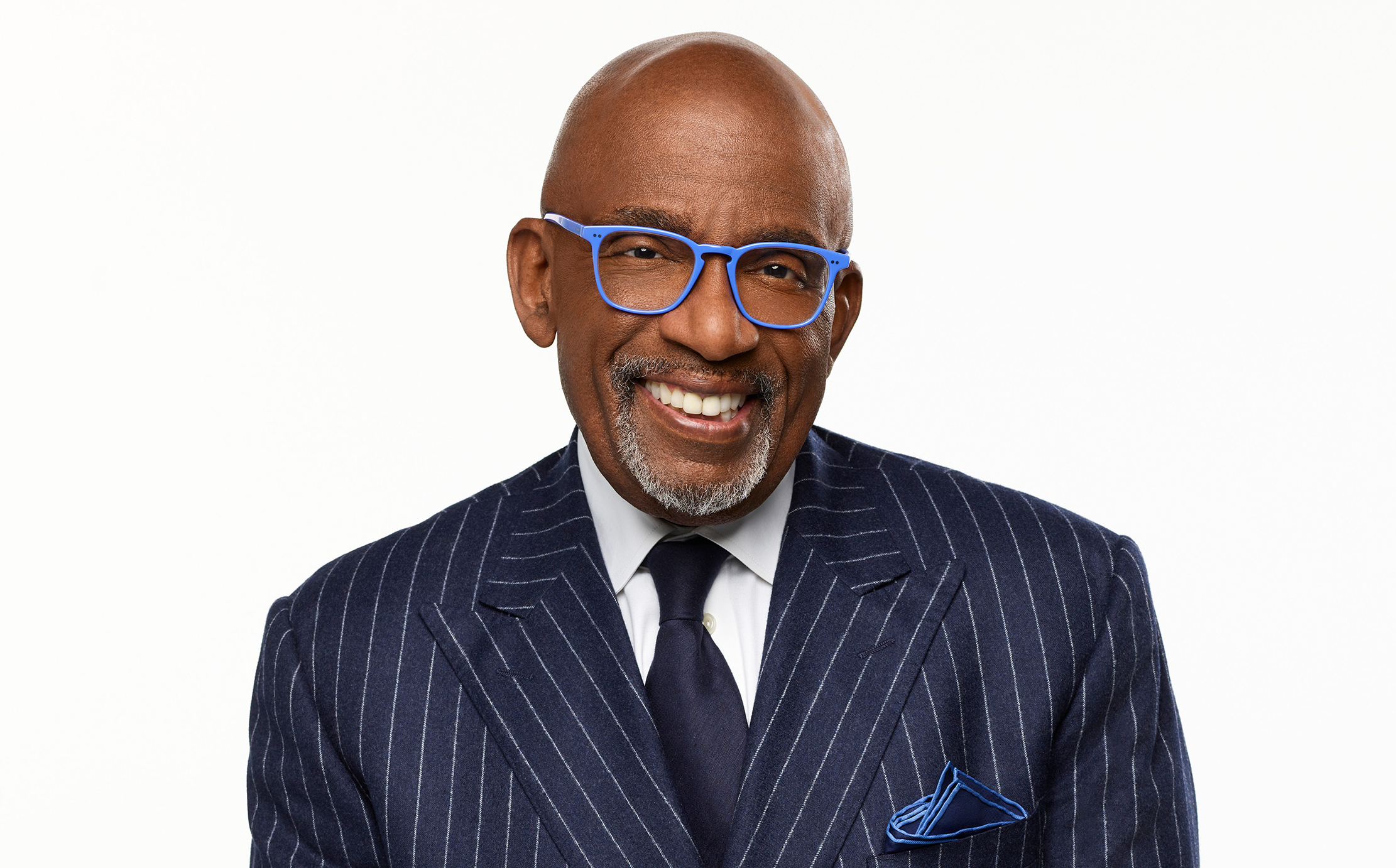

Al Roker, weathercaster for the Today show, is one of the most recognizable and trusted names in media. He has led efforts to educate the American public on the ties between weather and the climate crisis.

On this week’s Kicker, Roker and Kyle Pope, editor and publisher of CJR, discuss the evolution of weather coverage, from lighthearted entertainment to reporting on the front lines of the biggest story of our time.

SHOW NOTES:

Announcing the 2022 Covering Climate Now Journalism Award Finalists

TRANSCRIPT:

Kyle Pope: Talk to me about your interest in weather reporting. You started doing this when you were in college.

Al Roker: Right. And my interest in it was a paycheck. I was a radio and TV major, and I really had no interest in weather. I had no interest in being on television. I was going to be a writer or producer, something behind the camera. At the end of my sophomore year, a college professor put me up for a job doing weekend weather at the station he worked at in Syracuse, the CBS station.

It was one of those weird, serendipitous things in that I had taken a meteorology course, Intro to Meteorology, at the beginning of my sophomore year, and I had taken environmental science. I was kind of interested in it, but, you know, I had no intentions of following up. And then I got the weekend weather job. That was in May of 1974. And here I am today, very old and still doing it.

KP: You grew up in New York City, right?

AR: Yeah.

KP: You can test a theory that I have. I’ve lived here for twenty-five years or so, but I grew up in Texas. Weather seems less relevant in New York, in the city. I’ve lived in places where, like, you really track the weather, and it becomes a part of your daily life. It seems less so here. Did you? I mean, this was not on your radar as a kid?

AR: Well, no pun intended. My mother told me this, and I didn’t remember it, but there was a former Air Force meteorologist named Tex Antoine.

KP: That’s a great name.

AR: He was on Channel Four and then Channel Seven, and he was also an artist. He did kind of a Gnagy learn-to-draw, Bob Ross kind of thing. But he also did weather, and he had this character named Uncle Wethbee. He would dress Uncle Wethbee for the weather, obviously for the kids watching. I don’t know if you have ever heard of colorforms?

KP: No.

AR: It was a background, and you could put plastic pieces to dress up characters, things like that. Anyway, there was an Uncle Wethbee colorforms kit. I loved colorforms, and I had an Uncle Wethbee, so I would watch him on Channel Four, and he would tell you what to put on Uncle Wethbee, and so I would do that. It was like fate, I guess.

That’s a long way around of saying, when I was a kid I think I had the same interest as any other average kid or adult. Is it going to rain tomorrow? Is it going to be sunny? What’s it look like for the weekend? And I think in New York, people are just as fascinated with the weather as they are elsewhere. It’s just that it doesn’t quite affect us in the same way it would in the plains or down in Florida. We only have so much bandwidth.

KP: So when you first came in, this was still the era where the weather person was kind of the light part of the broadcast, right?

AR: Well, it depended on where you worked at, and I think it also depended on your station. If you worked in almost any local market, there was the “weather girl.” You know, a very attractive young woman who did weather. There was the funny, kind of more personality, who was probably the station staff announcer or whatever. And then there was usually the person who was an accredited meteorologist, a scientist on the air. There were obviously shades, gradations, and permutations of that formula. But I think in any given market, you would find some mix of those.

KP: Yeah. The fact that that was still the case in some of these markets, I mean, you said that you got into this because it was a job, and then you just sort of stayed. Was there ever a point when you were like, “Okay, this is enough. I’ve got to get out of this. I’ve got to do something else”?

AR: No, I didn’t. I did radio, disc jockey kind of stuff. And your stock-in-trade there is banter and talk. So that really kind of translated well to doing TV weather, as opposed to doing news, where you’re pretty much reading a script. With weather the map is your script, and the words just kind of go around it to transport you from one map to another. So I kind of fell into the right position, what I guess I was best equipped for, at least from a temperament standpoint. I’ve never not liked doing the weather.

KP: This background is so interesting to me, because fast-forward to where we are now, where the weather has taken on a whole different tone. The nature of the story is entirely different, because there’s a lot at stake, and it’s ominous, and it’s a bit scary. Was there a storm, was there an event where you were like, “Wow, the world is different and my job is different”?

AR: Superstorm Sandy. We tracked it for about a week. We went down to Florida and kind of rode up the East Coast, ending up in Point Pleasant, New Jersey. The destruction this thing caused, you know, up into New York and beyond, and then subsequent storms that season, like Hurricane Ida and more, was a sea change, no pun intended. You know, Superstorm Sandy, without making landfall in New York City, caused massive, massive destruction and death in Lower Manhattan, out in the Rockaways, and Staten Island, and even to the point where it changed the topography of New Jersey. That was like, “Okay, there has been a paradigm shift here in—not just weather and what these storms can produce, but in the way we’re going to have to cover it.”

KP: Did you have to sell that idea to NBC? Did you have to go to them and say, “Hey, you know, like, there’s something going on here, we’ve got to change the way we do this”?

AR: No. Listen, I can’t speak to other places, but it’s always been a place—“What’s the story and what do you need to follow it?” I mean, within reason—nobody’s given me a hurricane hunter plane. Obviously this is a different story, but it’s the same calculus as covering, say, racial injustice and what happened during the pandemic. Or to covering the pandemic. But as far as us being able to tell these stories, they’ve kind of left me to my own devices in that, “If this is what you want to do, by all means, go for it.”

KP: One of the reasons I want to talk to you is that you have been really leading the charge among weather reporters to put what’s happening in today’s weather in a broader climate context. How has that changed the way you go about your job? I mean, do you spend a lot more time reading UN reports? Do you have a different kind of Rolodex of people that you talk to?

AR: Well, here’s the great thing about being someplace like NBC News. Two years ago we started adding resources to what was our weather unit. And it’s more than a cosmetic name change—now it’s the NBC News climate unit. Within our news division, there’s the business unit, there’s a medical unit, there’s the consumer affairs unit, and then there is the climate unit. And what’s great is there’s a lot of interaction between those units. Weather and climate touches everything.

If there is extended drought in the west, which we’re seeing, and that changes the calculus for what’s grown and how it’s grown, that’s the business story. If there is a greater chance of a pandemic spreading because of a warming climate, it’s a medical-now-climate story. If allergy seasons are getting longer, and you’re seeing allergens in places that you didn’t before, again, that’s a medical story, but climate has touched that, so that we pool information.

And we’ve got a very robust group in just the climate unit itself, people with different backgrounds. Look, I’m not Joe Scientist, and I never pretended to be. I do not have a degree in meteorology. I have a love of information, and I love doing weather. And so, you know, I’ve got folks who say, “Hey, this is something we ought to look at.” They direct me to it, and that’s when I train my peepers on it. I’m just one guy, but we have a really great team that can bring that information into focus.

KP: You’re just one guy, but you’re often cited as one of the most trusted people in media, and you have a huge—

AR: Which is frightening, right?

KP: And you have a huge reach.

AR: What kind of world are we living in?

KP: Well, there you go. But we’ve been—through CJR and through Covering Climate Now—really trying to get media, especially television, to do more and better climate coverage, because we think the story warrants it. And one of the bits of feedback, not so much now, but even a year ago or two years ago, especially from television, was that “We’ve got to be careful, because people view the climate story as a downer,” or “They view it as a kind of political thing that we don’t want to get into.” What is your audience? What do you hear on that?

AR: See, that’s what I’m very curious about. Look, I’ve heard those same concepts, those same theories. But you know, when we do these stories, first of all, our overarching philosophy, policy is we’re not going to twist and turn something just to make a climate angle. Either there is or there isn’t, and either it’s verifiable or it’s not.

I think the average person—and you know, I almost hate that phrase. Put it this way, I think our viewers are smart. They know something’s going on. They get it. So our job is already halfway done. We do have a receptive audience; people do see that stuff is happening. Our job is to, (a), give them facts: we can’t say 100 percent that this will happen every time, but we can say that the likelihood of this happening is greater because of our warming climate. And I think our other mission is to say this is not hopeless, that there can be positives. People can make a difference—you, yourself, as an individual. And that if we put our collective will behind things, we can make changes.

You probably remember, it wasn’t that long ago we were talking about the hole in the ozone. We made policy changes. We made decisions in manufacturing materials. And, lo and behold, that hole is all but gone. So, granted, this is a much bigger issue: a warming climate. But we saw in the pandemic how quickly the planet started to heal itself when we were removed from the equation. Unfortunately, when we went right back to what we were doing, it didn’t take long for the emission levels to get back to where they were and then some.

Obviously, we can’t shut down a global economy and just go from one hundred to zero. But there are things we can do. And I think that’s our job also, to point out changes that people have made, both big and small. I’ll bet that’s for the good.

KP: And you have that, you have a degree of optimism, both personally, in your bones, that tells you this is something that we can sort out, and also as it relates to your kids?

AR: I think life and our experiences are a pendulum. I learned this from my wife, who is actually the real journalist in the family, Deborah Roberts. She said this country, it’s been known for swings. We go from one extreme to the other, and eventually we settle in the middle.

Most people know that there’s something going on, and I think the politicalization of this issue is going to eventually go away, because people are smart. They realize we need action, we need to do something. We need our governments, both from a town, a city, a state, and a federal level, to do things. And I think those things will get done.

The problem is we don’t know if they’ll get done in time and to a great enough degree to make a difference. We don’t know if we’ve reached a tipping point, and, if we reach a tipping point, what happens then. We can speculate. There’s been plenty written about it, but you know, it’s still anybody’s ballgame.

KP: Al, it’s great to talk to you.

AR: Oh, please. I do think we can do this. I really do. I look at the call logs, I look at our social media, and you’ll get one or two crackpot types. But most people, either nobody’s complaining about it, or people are actually saying, “Hey, thanks for that.” I think news executives and politicians underestimate the American public.

KP: I like to say that it’s the power of looking out the window. You know, if you want to know whether the climate is changing, just look out the window.

AR: Even something as simple [as] what used to be the traditional Tornado Alley is shifting. You know, as you’ve got a warmer Gulf, you’re seeing more moisture getting thrown into the atmosphere, and more fuel for these storms. And so the plains, the traditional Tornado Alley, those number of tornadoes are on a downward trend. The upward trend is the southeast, and a little further to the north, and into the Ohio River Valley, and a little further east.

To your point, you look out the window, and people are seeing more extreme cold, more extreme heat, more extreme drought. Storms that used to drop maybe half an inch to an inch of rain are dropping three, four, five inches of rain. And that affects people’s quality of life. It affects their economics, affects their insurance rates. It touches everything, and they know it. And that’s our mission, and to let people know when there are good things happening too. It’s a balancing act, but boy, it’s an important one right now.

KP: Yeah, thank you again.

AR: My pleasure, sir.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.