Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

We face a staggering array of foreign policy challenges today: climate change, extremism, epidemics, increasing inequality, threats of nuclear war, and cyber-attacks. Yet, somehow, we continue to underutilize a valuable resource to address these challenges: women.

The Women’s Media Center notes that when it comes to bylines and credits in 2017, 62 percent of bylines belonged to men; 38 percent to women. Sixteen percent of Pulitzer Prize winners have been women.

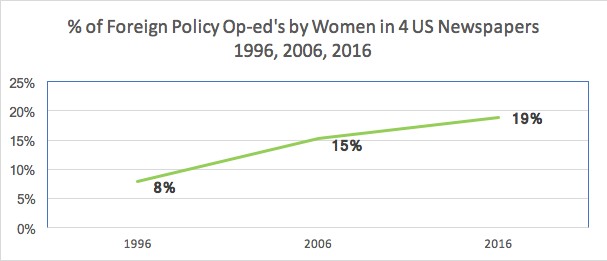

Women’s voices and perspectives are equally scarce on the op-ed page, a critical forum for influencing public opinion, promoting and affecting policy, and exerting leadership. To quantify the gender gap, Foreign Policy Interrupted, an organization that aims to increase female voices in the media, undertook a systematic review of foreign policy op-eds in 1996, 2006, and 2016 in the four largest newspapers in the US: The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and the Los Angeles Times.

ICYMI: You’re probably not quoting enough women. Let us help you.

We found that we are far from gender parity on the op-ed page, and it’s not changing fast enough.

FPI identified 3,758 foreign policy op-eds across the three one-year periods. These articles spanned global affairs, national security, war, development, human rights, global trade and commerce, and bilateral and multilateral issues. Of these, 568, or 15 percent, were written by women.

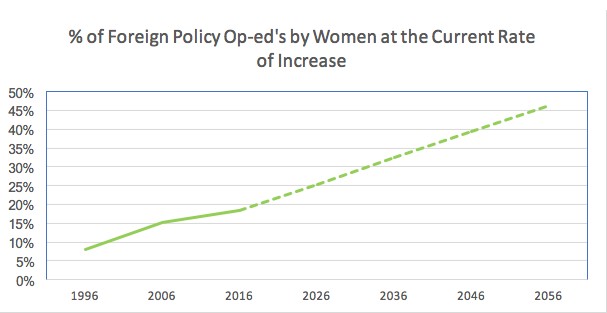

At that rate, we won’t approach parity until 2056, a full professional generation from now.

The total number of op-eds by women has increased rapidly in two decades—from 58 in 1996 to 250 in 2016. However, this largely reflects the increase in total content available through online platforms, rather than an improvement in parity. Across the four publications combined, the proportion of op-eds authored by women increased more modestly over time: from 8 percent in 1996, to 15 percent in 2006, to 19 percent in 2016.

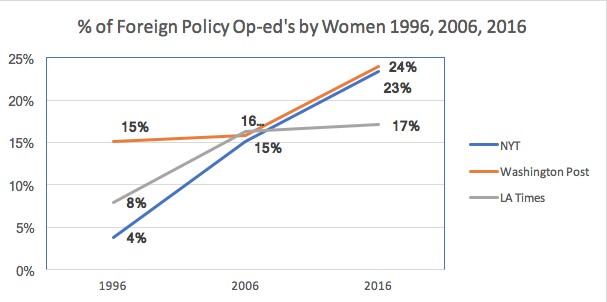

In the Times and the Post, women’s share of op-ed bylines has increased over time from 4 percent and 15 percent to 23 percent and 24 percent respectively. In the LA Times, the share of female bylines also increased, from 8 percent to 17 percent, though the number of foreign policy op-eds published by the LA Times decreased.

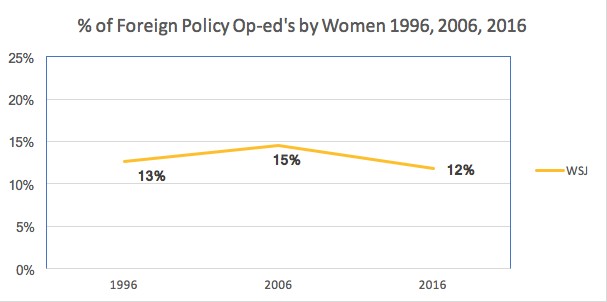

The increase in equal representation did not hold across all publications. In The Wall Street Journal, women were no better represented in 2016 compared to 1996—fewer than one in eight foreign policy opinion pieces was authored by a woman.

The FPI review shows that the share of women’s bylines has increased by as much as 7 percentage points per decade. At that rate, we won’t approach parity until 2056, a full professional generation from now.

The tendency to publish the same bylines and quote the same sources repeatedly is partly driven by the pressure on today’s media to produce more content with fewer resources. When breaking news hits, daily beat journalists eager for sources reach out to the first people they can find working on and influencing any given issue, not the experts working outside the nerve center or think tank world. This gives men, who dominate the top spots in think tanks, the Pentagon, the State Department, National Security Council, and White House an advantage. The Wall Street Journal, for example, published seven pieces by John Bolton in 2016.

This also leads to a self-reinforcing cycle: the more you are heard, the more influential you become. The numbers are daunting, but the problem is not intractable. There is no shortage of qualified women in the pipeline; Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, Tufts’s Fletcher School, and Johns Hopkins’ School of Advanced International Study all had more than 50 percent female enrollment in 2016.

There are clear steps to increasing the diversity of voices and thought leaders in foreign policy—and other fields where women’s voices are lacking. Editors need to widen their scope, and solicit and consider pitches from a more diverse range of voices and a more equal mix of women and men. Likewise journalists should be vigilant about reviewing their quoted sources to make sure they’re reaching out to women, too.

ICYMI: A climate of hate toward the press at Trump rallies

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.