Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

White House press secretaries make a good salary—around $183,000 a year, almost half the president’s pay. But taxpayers are getting a bargain in Kayleigh McEnany, who has taken on two roles: first, as the president’s spokesperson, and second, as a media critic, offering unsolicited but carefully researched and rehearsed critiques of news coverage writ large.

McEnany, a Harvard Law graduate who got her start as a combative Trump supporter on CNN, has been press secretary for less than three months. It’s dicey to make a lot of predictions about her future, given that she is the fourth person to hold this job in three-and-a-half years, succeeding Sean Spicer (182 days), Sarah Huckabee Sanders (705 days), and Stephanie Grisham (281 days). (All of them lasted longer than 11-day White House Communications Director Anthony Scaramucci.)

McEnany got off to a promising start with her first briefing on May 1: “I will never lie to you. You have my word on that,” she told reporters in the White House briefing room. And then, at the same briefing, McEnany made clear that she, like Trump, sees herself as an assignment editor. She was asked about Michael Flynn’s efforts to pull back on his guilty plea for making false statements to the FBI. She responded by telling the press corps that they were, in essence, asking the wrong question, and should instead focus its attention on an FBI agent’s notes (“What’s our goal? Truth/Admission or to get him to lie?”) written before the Flynn interview.

Here was her admonition to the press:

I would encourage the media to cover it, because I’ve watched a lot of your networks, I’ve read a lot of your papers. I’ve seen a whole lot of scant information about Michael Flynn, when there was a whole lot of speculation about “Russia, Russia, Russia”

Fair enough. A press secretary isn’t doing her job right if she isn’t trying to divert reporters’ attention from unfavorable stories.

But within days, McEnany started tacking in a different direction. Not content just to suggest angles for reporters, she waited for a question —an irrelevant one, as it happened—to launch broadsides against journalists’ conduct.

On May 6, a reporter asked McEnany about a comment she’d made before her current role; in February she had told Fox News that “we will not see diseases like the coronavirus come here.” While the reporter asked the question, McEnany could be seen sifting through notes on the podium. After offering a short, unconvincing answer to the question, McEnany channeled her modern-day Walter Lippmann:

I would turn the question back on the media, and ask similar questions: Does Vox want to take back that they proclaimed that the coronavirus would not be a deadly pandemic? Does the Washington Post want to take back that they told Americans to “Get a Grippe,” the flu is bigger than the coronavirus? Does the Washington Post, likewise, want to take back that our brains are causing us to exaggerate the threat of the coronavirus? Does the New York Times want to take back that fear of the virus may be spreading faster than the virus itself? Does NPR want to take back that the flu was a much bigger threat than the coronavirus? …

I’ll leave you with those questions, and maybe you’ll have some answers in a few days.

Then she grabbed her binder, flashed a smile and walked off the dais.

Some of McEnany’s onstage correctives ought to come with their own corrections. She criticized the press again on May 28, again while consulting her notes:

You mentioned that the media apologizes for their mistruths. I mean, I’m sitting here looking at their headlines. The New York Times saying, “There Aren’t Enough Ventilators to Cope With the Coronavirus.” In fact, we had an excess of ventilators we’ve shipped around the world. Washington Post, “U.S. health system is showing why it’s not ready for a coronavirus pandemic.” We were ready.

Neither of those statements is true. Particularly in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, doctors were struggling to retrofit ventilators to serve multiple patients, while medical personnel resorted to wearing trash bags and snorkel masks because of the shortage of PPEs.

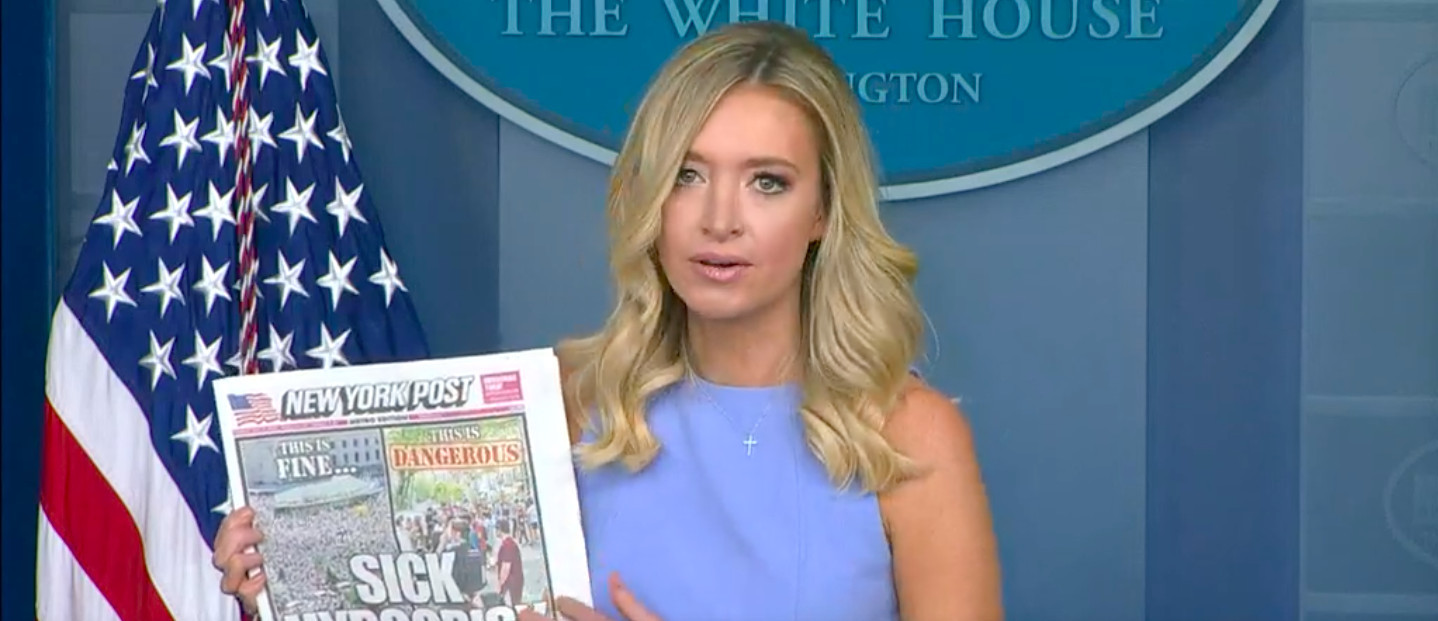

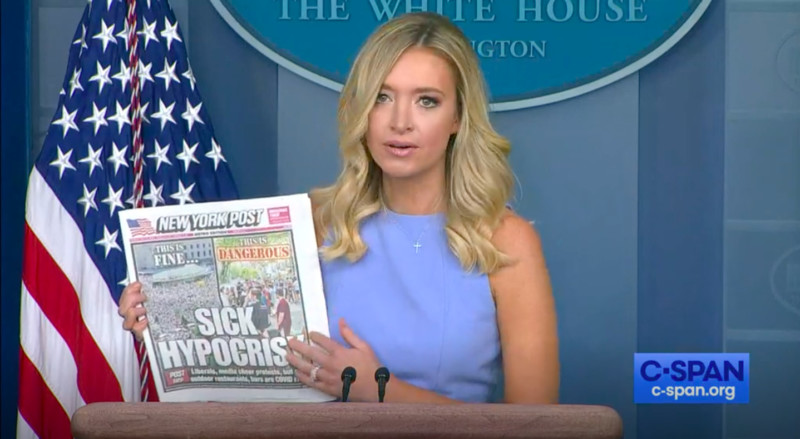

Screengrab via C-SPAN

Now, no critic can grouch all the time. On rare occasions, McEnany will take a moment to compliment a news organization. She was particularly pleased earlier this month with the New York Post’s “SICK HYPOCRISY” cover, which, she said, “highlights the hypocrisy of the media where: This is OK—protesting. This is not OK—Trump rallies. It’s really remarkable, and I think the American people have taken notice.”

When McEnany pivots from reporters’ questions to go off on unrelated diatribes, she is seeking to undermine the credibility not just of individual journalists or outlets, but of journalism itself.

Just because she works for a boss who has racked up nearly 20,000 lies and misstatements since 2017, that doesn’t mean she’s always wrong. Asked about Trump’s string of “false and misleading statements,” McEnany cited some of the media’s “most egregious” errors, including ABC’s disastrously flawed 2017 report that Trump had asked Flynn to reach out to the Russians during the campaign—which the network first “clarified” and then corrected altogether.

Gamblers would call such an episode “the tell.” McEnany demonstrated that her goal isn’t to respond directly to these questions, or even to engage in a dialogue about journalistic ethics. It is to throw up so much chaff into the media’s radar that even the most basic critique is deprived of meaning.

We saw this again last week, when she was asked why the president posted a video of two toddlers that had been manipulated with a false chyron. McEnany quickly pivoted to an entirely unrelated incident from early 2019:

He was making a point about CNN specifically. He was making a point that CNN has regularly taken him out of context. That, in 2019, CNN misleadingly aired a clip from one viewpoint repeatedly to falsely accuse the Covington boys of being, quote, “students in MAGA gear harassing a Native American elder.” That’s a harassing video, a misleading video about children that had really grave consequences for their futures.

And when McEnany was challenged a few days later on why Trump used the term “Kung Flu” in his recent Tulsa rally, she responded by citing news organizations’ terms to deflect the racism of her boss:

The New York Times called it the “Chinese coronavirus;” Reuters, the “Chinese virus;” CNN, the “Chinese coronavirus “on January 20; Washington Post, January 21st, “Chinese coronavirus.” And I have more than a dozen other examples.

McEnany is a hit in many circles. Ari Fleischer, who served as George W. Bush’s press secretary, applauded her first appearance: “She nailed it. She was in command of facts, and she spoke knowledgeably and comfortably from that podium.” McEnany’s citation of Vox and Washington Post stories “threw the press for a loop,” tweeted the Washington Examiner. David Brody from the Christian Broadcast Network swooned: “I feel like we need some ‘Gladiator’ music when she comes in or leaves. You know, Mel Gibson, ‘Braveheart,’ the whole thing.”

And McEnany is very much a product of this administration. “She is using the press as a foil … prepared with salvos to the press that are aimed at [Trump’s] base,” says Martha Kumar, a scholar of the presidency who has written about the role of press secretaries. Kumar told me that McEnany reflects something “really unusual”: Trump’s “interest in delegitimizing government institutions, but also the media. I see her as an instrument of him.”

Press secretaries, both the good ones and the bad, have a job to do: sell the best possible versions of their bosses. To make that work, they must regularly slather the glossiest varnish on the gnarliest stories. When they’re most successful, they spin narratives to the president’s advantage, deterring or shading the most damaging stories while highlighting those that are most beneficial.

McEnany does that, but her carping at press conduct and headlines has a deeper purpose. When she pivots from reporters’ questions to go off on unrelated diatribes, she is seeking to undermine the credibility not just of individual journalists or outlets, but of journalism itself. When confronted with a tweet or quote that might work to Trump’s disadvantage, she tries to undermine the press rather than to address the substance of the story. That is why she comes armed to briefings with multiple examples of press failure—some valid, some fictitious—and draws White House reporters into a noxious tit for tat.

It is no mystery why this is her line of attack. The more interesting questions are whether the press is obliged to be a party to it—and whether the public learns much from it. That’s grist for a future column, so if you have thoughts, please let me know at bgrueskin@columbia.edu.

THE KICKER: Ed Yong on COVID-19 and American fatalism

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.