Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

When Senator Elizabeth Warren remarked during a recent campaign event that Native Americans should be “part of the conversation” about proposed reparations, her quote quickly ascended a benighted editorial chain, generating national headlines. In doing so, it also cast light on how poorly politicians and journalists in the US understand matters significant to Indian Country. The heart of the Indigenous struggle in America concerns treaty rights and an ongoing effort to ensure the federal government lives up to these historic pacts. For Native Americans, the senator’s comment was a non-story, even a potentially damaging one. Journalists might have detected the contradiction, if only they had asked.

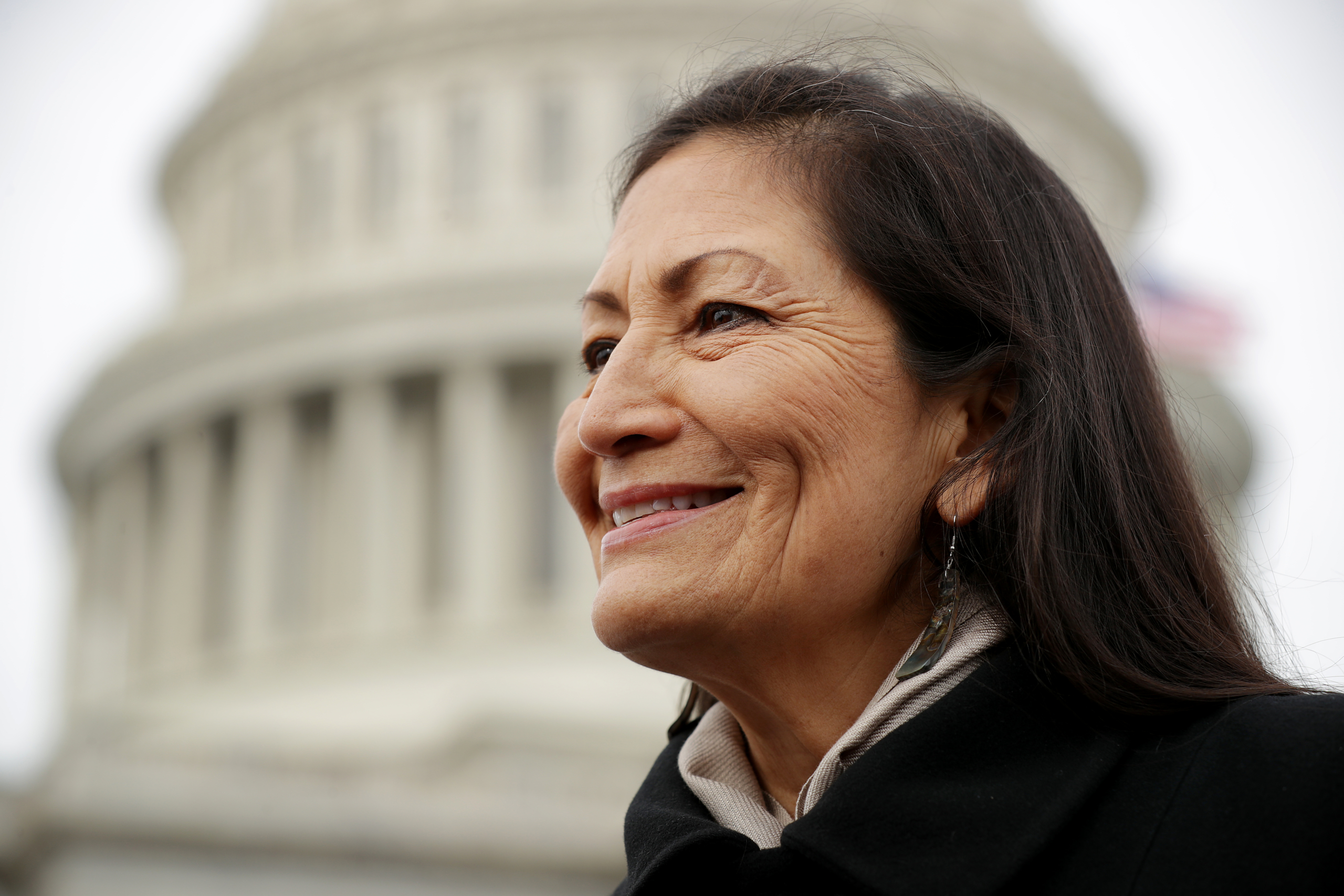

The historic election of the first two Native American congresswomen, Representatives Deb Haaland, from New Mexico, and Sharice Davids, in Kansas, has brought greater Indigenous representation to a news cycle too often fixated on Warren’s controversial claims to Cherokee ancestry and President Donald Trump’s mocking responses. But such gains have been vulnerable: when USA Today illustrated the most diverse Congress in US history, its graphic excluded any mention of Native Americans, the only demographic to double in size in the US House.

Native Americans suffer from chronic misrepresentation and erasure by an established press, which continually fails to acknowledge the Indigenous timeline. This crisis—a word not used enough to describe Native Americans’ efforts against invisibility—is stoked by the stark absence of Indigenous journalists in newsrooms and further complicated by an Indigenous media largely owned by tribal governments and entities.

ICYMI: Last year’s headlines are in danger of disappearing forever

There are roughly 2.6 million tribal citizens in America and they are of every stripe. Their socioeconomic outcomes and access to education are often determined by pervasive inequality and discrimination; this lack of access also limits their representation in American media. Compared to other colonizing nations with sizeable Indigenous populations—Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Norway—the US lags far behind when it comes to including Indigenous affairs in daily news coverage.

Statistically, it’s rare for a Native American journalist to join the staff of an elite newsroom, much less to report for such an outlet on “Indian Country,” the legal term for the nation’s 326 Indian reservations and, more colloquially, the smattering of US cities where the majority of Native Americans live. Less than .05 percent of all journalists at leading newspapers and online publications are Native American, according to 2017 data from the American Society of News Editors. The odds that an established media outlet will hire an Indigenous reporter in a capacity to write exclusively about the lands and issues they know well is virtually unheard of. There is no beat in the American legacy press devoted solely to covering the country’s 573 tribal nations. But there should be—and it should be assigned to an Indigenous journalist.

An Indigenous journalist is more likely to cover stories that are currently overlooked. Consider recent attention to the blackface scandals that launched a political crisis in Virginia alongside the issue of redface, which persists in the form of racist mascots at many a sporting event televised in America. While the histories of blackface and redface differ, they originate from white supremacy, an inescapable issue in today’s national dialogue. The difference, then, is shock value—a palpable disparity in levels of outrage that, from an Indigenous view, is perhaps the most shocking aspect of all.

In January, viral video showed Covington Catholic students jeering at a Native American activist as he played his buckskin drum. At one point, the teenagers were seen gesturing the “tomahawk chop,” an imitation of a violent war maneuver that has been widely reproduced in offensive mascotry. The incident sparked a bizarre and painful-to-watch week of reporting by a homogeneous press struggling to racially decode the students’ actions. Stacy Leeds—a tribal citizen of the Cherokee Nation and the only Native American woman to serve as dean of a US law school—tweeted about the incident: “When children are raised to think racist mascots are harmless and they see people chuckle (or say nothing) as someone is taunted with Redskin/Chief/Pocahontas – it leads to this.” Two days after the Covington incident, Kansas City Chiefs fans performed the chop and chant for all to see on national TV during the AFC Championship Game. Whether many viewers connected the two incidents is impossible to say. Most journalists didn’t.

Writers from Indian Country—including scholars, activists, policy analysts, and some journalists—produced a great deal of political commentary following the Covington incident. But with little exception, Indigenous journalists did not provide news coverage for the established press.

Without credibility or authentic representation, Indigenous journalism is greatly impacted by potential funders, future collaborators, and perhaps outsiders who think they can best Indigenous business models with fresh approaches—ones that could very well exclude Indigenous efforts to sustain the narrative.

There are some attempts to respond to the current crisis in covering Indian Country. In Arizona, Navajo reporter Shondiin Silversmith was recently assigned to a devoted beat covering the state’s 22 federally recognized tribal nations for The Arizona Republic, one of the few beats of its kind at a statewide daily newspaper. Several other Indigenous journalism projects are slated across the country made possible by unprecedented funding from Report for America. And Arizona State University will appoint a new professorship in the US to begin researching “Native American Journalism.”

These efforts are exciting; still, best-laid plans for Indigenous Peoples have often been made with a lack of informed and engaged Indigenous input. Scrutiny should be exercised at every turn. Take, for example, High Country News. Since launching its Tribal Affairs desk in June 2017, my recent review found that, as of December 2018, the majority of authors writing the Indigenous narrative for the publication are not tribal citizens of federally or state-recognized tribal nations. Out of 140 dispatches examined, Native male journalists authored 38 percent of stories—the same portion as written by non-Native women, but outnumbering up to four times dispatches filed by Native American women journalists. High Country News Editor in Chief Brian Calvert disputes this count, saying that, as of March 2019, 56 percent of stories have been written by Indigenous writers, overtaking the 51 percent written by Native and non-Native women.

“High Country News maintains a healthy mix of Indigenous and non-Indigenous writers, balanced between men and women, all of whom are centering Native voices for a Native audience and telling significant stories that that would not otherwise be told,” says Calvert. “We are learning from our mistakes, correcting as we go, and writing the stories of Indian Country one day at a time.” (Disclosure: I have previously published stories at High Country News.)

There’s a second issue, as well. While many contributors to HCN are Native American (including one writer of Aboriginal Australian descent), they represent a pool of voices linked to activism, advocacy, and agenda-driven platforms at a rate which outpaces dispatches from Native American journalists. How Indigenous journalism is packaged and perceived has incredible power to influence actions, policies, laws, and points of view that affect all Americans, including Native Americans. But without credibility or authentic representation, Indigenous journalism is greatly impacted by potential funders, future collaborators, and perhaps outsiders who think they can best Indigenous business models with fresh approaches—ones that could very well exclude Indigenous efforts to sustain the narrative.

According to a recent report by the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance, roughly three-fourths of the estimated 200 Indigenous media platforms that exist in the US are owned and/or operated by a tribal nation or entity, which poses a clear challenge to accountability journalism; Indigenous outlets are torn between reporting on their own tribal structures and representing Indigenous people to the rest of the country. Often, legitimate Indigenous outlets end up being seen as agenda-driven, causing them to be subtly de-legitimized by the mainstream press. When the Associated Press, for instance, issued a correction over its reporting of the Covington Catholic matter, rather than owning up to its flawed fact-checking unconditionally, the AP called out the news outlet, Indian Country Today, as the source of its misinformation, a subtle and familiar industry-wide condescension detected even in my own reporting experiences and leading to situations such as my 2017 arrest while filing dispatches from Standing Rock.

But neither can Indigenous outlets ignore opportunities to speak to the country. When Tristan Ahtone, president of the Native American Journalists Association, denounced the “mainstream media” for its handling of the Catholic Covington controversy, ironically the Kiowa journalist turned to the very establishment he was repudiating as a platform to air his differences. In an opinion essay, “This mishandling of the MAGA teens story shows why I gave up on mainstream media,” Ahtone calls for “subscribers, supporters, philanthropists and private foundations” to divest from elite journalism—in the pages of the The Washington Post. It’s ironic, to be sure, but to ignore the power and credibility of the established press would mean disregarding the promise that the establishment holds in amplifying Indigenous voices.

And there is a hunger for these voices. Mainstream scientists, for example, have begun turning to Indigenous subsistence hunters as way to better understand the effects of climate change. At a time when there is much at stake, the scientists have identified immense value in traditional knowledge systems that, for centuries, have supported Indigenous survival. Journalistically, the Indigenous narrative holds the same unique power to shift how we, as a society, see the world. Take the Irish potato famine. Some of the best reporting didn’t come from Europe, but from tribal newspapers in Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma. The Cherokee and Choctaw, still recovering from their own forced removal, understood Irish suffering at a level that went deeper than mainstream headlines. When it seems the unwinding of America accelerates daily, Indigenous understanding could be an extraordinary source for enlightenment. But it must first be valued.

Eventually, the goal is an intentional integration of Indigenous perspective into the dominant narrative. Standing Rock provides the most potent case study for why this is necessary. Coverage by elite news outlets, while initially slow and reactionary to the pipeline protests, ultimately exposed the militarized police violence on Indigenous water protectors opposed to the Dakota Access Pipeline and explained an Indigenous consciousness rooted in 500 years of anti colonial resistance to such encroachment. It also acknowledged the value of rethinking time, space and connection to the land—a decolonization predicated on traditional knowledge systems held in the highest regard among Indigenous Peoples. For the first time, many Americans identified with Indigenous resilience.

“We have an opportunity to change our narrative—to weave ourselves a story moving forward in the fabric of America,” said Representative Haaland at the 2019 State of Indian Nations Address before the National Congress of American Indians.

For the Laguna Pueblo congresswoman, she spoke of reclaiming the Indigenous narrative with the same urgency and importance as protecting Bears Ears, the homeland of her ancestors and also of mine. Their stories are still etched in stone on the mesas and bluffs jutting from the desert. To anthropologists, the ancient handprints and carved symbols are petroglyphs explained in scholarly account. But rarely are these stories interpreted as original sources of journalism; as pre-colonized thought deeply connected to time and place. But they are America’s earliest through-lines, and they have never faded. To understand the story of this nation is to honor its entire narrative.

Podcast: Mueller, Barr, and what journalism can do when the judicial system fails us

This article was supported in part by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

This post has been updated to include an author disclosure.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.