Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

It was just before midnight, on June 14, 2017, when James Bennet, then the New York Times’ editorial page editor, sent an anxious text to a Washington colleague.

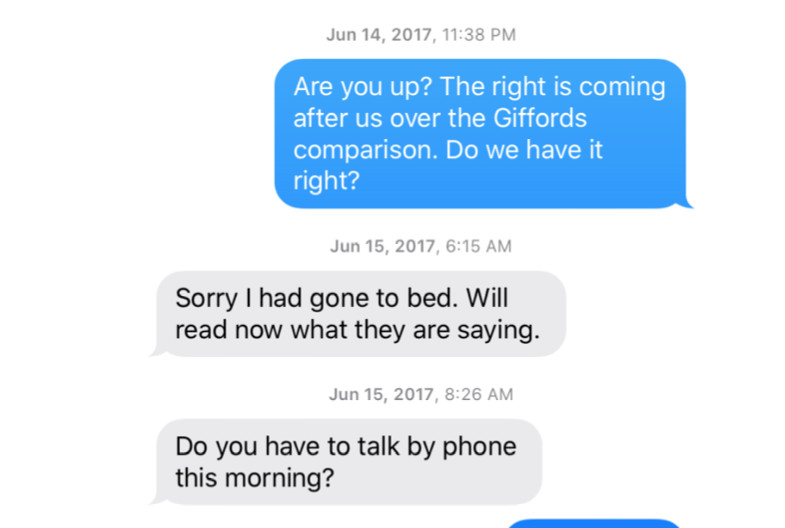

“Are you up? The right is coming after us…”

A few hours earlier, Bennet had rewritten that staffer’s editorial about two political assassination attempts, and inserted serious errors in the process. Bennet was correct about one thing, though: the right wing was coming after him and the Times. And the counterattack wouldn’t be limited to an angry Twitter mob.

Within days, the Times was sued by Sarah Palin, the former Alaska governor and vice presidential candidate, who said she’d been defamed by the editorial’s incorrectly accusing her of inciting a violent shooting in Arizona. Highly public figures like Palin usually have a hard time mounting such suits. But late last month, US District Judge Jed S. Rakoff decided that the suit could go to trial next February.

In recent days, I have reviewed depositions, statements, story drafts, emails, and texts by key players in the case: Palin, Bennet, Elizabeth Williamson (the Times writer who sent in the original version of the editorial), and other staffers. The documents, on file at the federal District Court in Manhattan, showcase a series of errors, some of which the Times acknowledged hours after it published the editorial. But they also reveal systemic problems in the way that Times writers and editors interact, especially when operating under deadline and in distant bureaus.

Despite the judge’s ruling, Palin faces significant hurdles. As, indisputably, a public figure, she must prove, before a New York jury, that the Times acted with “actual malice” or “reckless disregard” for the truth, and do so with “clear and convincing” evidence. (Roughly, this would mean they knew that what they wrote about Palin was false and published it anyway, or were astoundingly reckless in not caring whether it was true or false. For more on the legal battles, read Erik Wemple’s excellent coverage in the Washington Post.)

The Times has called the errors “an honest mistake,” and a spokeswoman told me this week that the company is “confident we will prevail before a jury.” Bennet and Williamson declined to comment for this story.

Bennet, fifty-four, had two stints at the Times—first as a correspondent in the White House and Middle East, and then, starting in 2016, as editor of the editorial page. In between, he ran The Atlantic, which he transformed into a digitally adept news organization that featured such stellar writers as Ta-Nehisi Coates and Caitlin Flanagan. But he stepped down from the Times in June amid an incident unrelated to the Palin suit. His page published an op-ed by Sen. Tom Cotton, titled “Send In the Troops,” and Bennet later acknowledged he hadn’t read the piece before it ran. The op-ed ignited an open revolt by some news staffers, particularly journalists of color who felt it served as a call to violence against their communities. Bennet’s resignation marked a startling comedown for a journalist who was seen as a top contender to succeed Times executive editor Dean Baquet.

Palin’s lawsuit stems from an editorial on the shootings of GOP congressman Steve Scalise and several others during a June 2017 baseball practice in Alexandria, Virginia. The gunman, a Bernie Sanders supporter, was killed by police.

But the problem with the piece goes back to 2011, when Jared Loughner shot into an Arizona crowd around Democratic congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords. Six people, including a federal judge and a nine-year-old girl, died, and Giffords remains impaired from her wounds. (Her husband, Mark Kelly, is a Democrat running for US Senate this fall.) At the time, some commentators sought to connect the shooting to a map from Palin’s political action committee that put stylized crosshairs over twenty congressional districts, including Giffords’s. (Palin’s accompanying Facebook post also stated, “We’ll aim for these races and many others. This is just the first salvo…”) Nevertheless, investigators found no link between the map and Loughner’s shooting spree.

Six years later, the idea for an editorial on the Alexandria shooting came from Williamson, a Washington-based edit-page writer who had previously reported in the US and abroad for the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post. A few hours after the bullets flew, according to her deposition, she sent an email to colleagues with the subject line, “Are we writing on the congressional shooting?” An editor responded, “Can’t see it yet, but keep looking. A nutcase who hates Republicans???”

For the next few hours, Williamson and other edit-page staff researched motives for the shooting. Mid-afternoon, Bennet contributed to an email string: “Did we ever write anything connecting…the Giffords shooting to some kind of incitement?” A colleague offered up a 2011 column in which Frank Rich mentioned Palin’s map but noted that “we have no idea” if Loughner had seen it before the shooting, adding, “nor does it matter.”

Williamson sent her piece to New York headquarters around 4:45pm. She focused, in part, on gun control, though she did reference Palin’s map. Williamson also included a link to an ABC News article that ran shortly after the Giffords shooting. The article states, in the tenth paragraph, that “no connection has been made between this graphic and the Arizona shooting.”

In New York, editors started working on her draft. In a deposition last spring, Williamson was asked what she did “with respect to the editorial before it was first published online.” She replied with words familiar to anyone who has worked in a bureau far from the home office: “I filed my draft, and after that, it was in New York, and they did what they were going to do.”

In New York, Bennet read Williamson’s editorial but wasn’t satisfied. “It was very much a first draft and…it wasn’t exactly accomplishing the objectives that we had set out that morning to achieve. [It] read to me much more like a summary of the news.” Bennet said he wanted a piece that “conjured the sense of the horror of the day.” And he had an eye on the clock: “I was concerned about the deadlines approaching. We just didn’t have that much time, and I wound up plunging in and just beginning to effectively rewrite the piece.”

He zeroed in on the Palin angle. While Williamson’s original version mentioned Palin’s crosshair map, she avoided assigning a direct link between it and the Giffords attack:

Just as in 2011, when Jared Lee Loughner opened fire in a supermarket parking lot, grievously wounding Representative Gabby Giffords and killing six people, including a nine-year-old girl, Mr. Hodgkinson’s rage was nurtured in a vile political climate. Then, it was the pro-gun right being criticized: in the weeks before the shooting Sarah Palin’s political action committee circulated a map of targeted electoral districts that put Ms. Giffords and 19 other Democrats under stylized crosshairs.

Bennet took that paragraph out and replaced it with this section (boldface is mine):

Was this attack evidence of how vicious American politics has become? Probably. In 2011, when Jared Lee Loughner opened fire in a supermarket parking lot, grievously wounding Representative Gabby Giffords and killing six people, including a nine-year-old girl, the link to political incitement was clear. Before the shooting, Sarah Palin’s political action committee circulated a map of targeted electoral districts that put Ms. Giffords and 19 other Democrats under stylized cross hairs.

Conservatives and right-wing media were quick on Wednesday to demand forceful condemnation of hate speech and crimes by anti-Trump liberals. They’re right. Though there’s no sign of incitement as direct as in the Giffords attack, liberals should of course hold themselves to the same standard of decency that they ask of the right.

The column then got another edit, but Palin wasn’t the focus. “I remember we had quite a bit of back-and-forth between James about the headline,” recalled Linda Cohn, an editor under Bennet.

After he finished his rewrite, Bennet sent an email to Williamson, contrite over how he had big-footed his staffer: “I really reworked this one. I hope you can see what I was trying to do.… I’m sorry to do such a heavy edit.” Minutes later, Williamson responded, “No worries the lede does a much better job of conveying how incredibly awful this was.… And I could tell from your messages that you were keen to take this on! Looks great. E.”

His two references to “incitement” proved key to the lawsuit. Not long after Palin filed her suit, Bennet testified in a hearing before Judge Rakoff. Asked about his rationale for pumping up Williamson’s draft, Bennet offered reasons ranging from a Thomas Friedman column to his own years as a Jerusalem correspondent.

But the judge wanted clarity: “I am asking a question about grammar and sentence structure, which presumably you have some expertise in.” He read the first “incitement” passage back to Bennet and asked, “Doesn’t that mean as a matter of ordinary English grammar and usage that that sentence is saying that the shooting in 2011 was clearly linked to political incitement?” Bennet fumbled for a while, so the judge zeroed in again: “You’re saying that this map circulated by Sarah Palin’s political action committee was a direct cause of the kind of political incitement that you think led to various acts of violence?” Bennet responded, “I would not use the word ‘cause,’ Your Honor” and later added, “It wasn’t in my head that that was tantamount to complicity in attempted murder. It’s simply rhetoric.”

Bennet was then asked if he had looked at the Palin map. No, he said. “I was not reporting the editorial.… I was editing it, and so I was working from the draft that was in front of me on a tight deadline.”

The editorial, headlined “America’s Lethal Politics,” went online around 9pm; meanwhile, the news side of the Times published a story that also mentioned Palin’s crosshairs map, but crucially, it stated that “no connection to the [Arizona] crime was established.”

Within an hour or so, Twitter exploded. And it wasn’t just conservatives. MSNBC anchor Chris Hayes added this to a thread excoriating the Times: “Let me chime here to say: yeah, that’s nuts.”

At 10:35pm, editorial writer Ross Douthat emailed Bennet: “I would be remiss if I didn’t express my bafflement at the editorial we just ran.… There was not, and continues to be so far as I can tell, no evidence that Jared Lee Loughner was incited by Sarah Palin or anyone else, given his extreme mental illness and lack of any tangential connection to that crosshair map.… I don’t normally raise issues with our editorials…but I felt I should express my confusion in this case.” Bennet responded about a half hour later, not really addressing Douthat’s point: “I’ll look into this tomorrow. But my understanding was that in the Giffords case there was a gun sight superimposed over her district.”

Despite the late hour, the edit page realized there was a big problem. At 11:11pm, editor Jesse Wegman sent an email to Williamson: “Did James add that line about Giffords and Palin?” She responded, apparently without having closely examined the rewrite: “No, I had a version of that in my draft.” Then Williamson went to bed, while Bennet sent his anxious 11:38pm message: “Are you up? The right is coming after us over the Giffords comparison. Do we have it right?”

Most print journalists know what faced the edit page that night: You’ve sent the type to the pages, and the pages to the presses, and then you realize there’s a terrible mistake in tomorrow’s paper. And you can’t do a damned thing about it.

Bennet was up early the next day, with a 5:08am email to colleagues: “Hey guys—We’re taking a lot of criticism for saying that the attack on Giffords was in any way connected to incitement.… I don’t know what the truth is here, but we may have relied too heavily on our early editorials and other early coverage of that attack. If so, I’m very sorry for my own failure on this yesterday.… I’d like to get to the bottom of this as quickly as possible this morning and correct the piece if needed.”

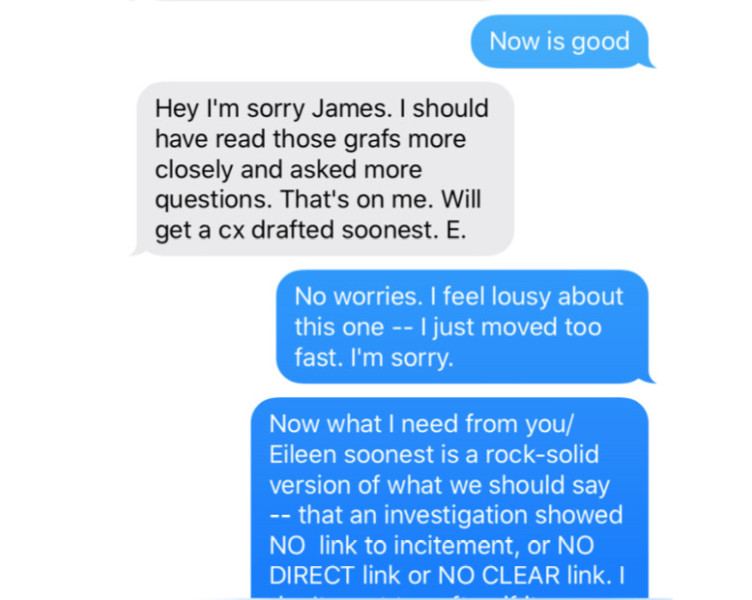

Williamson awoke and started texting Bennet. She was deferential to her boss and unduly apologetic for her own actions: “Hey I’m sorry James. I should have read those grafs more closely and asked more questions. That’s on me. Will get a cx [correction] drafted soonest.” Bennet texted back, “No worries. I feel lousy about this one—I just moved too fast. I’m sorry. Now what I need…soonest is a rock-solid version of what we should say—that an investigation showed NO link to incitement, or NO DIRECT link or NO CLEAR link.”

That morning at the edit-page office, “the room was abuzz” with word of the screwup, as Cohn put it: “There was a general gasp in the room, like, ‘Oh, my God. How could we get this wrong?’ ”

The staff set to work to fix things up—and then botched the correction. The edit page initially tweeted, “An earlier version of this editorial incorrectly stated that a link existed between political incitement and the 2011 shooting of Representative Gabby Giffords. In fact, no such link was established.” There was no mention of the map. Later, the Times needed to add: “The editorial also incorrectly described a map distributed by a political action committee before that shooting. It depicted electoral districts, not individual Democratic lawmakers, beneath stylized cross hairs.” The Times also removed references to “incitement” from the online version of the editorial.

Neither correction mentioned Palin, and when asked later if he ever told her he was sorry, Bennet said, “We did not apologize to her.” He also told CNN that the “error doesn’t undercut or weaken the argument of the piece.”

Less than two weeks later, Palin filed her suit. She has steadfastly denied any tie to the Giffords shooting. Asked about the map in a May 2020 deposition, she called those crosshairs “pinpoints of what we were talking about, the districts that we wanted voters to focus on.… I certainly didn’t make any connection—‘Hey somebody, get a gun and do something stupid with a gun based on this.’ ” Why did her pac say, “We will aim for these races”? She explained, “Well, ‘aim’ is used a lot in a lot of different ways. I’m sure if a hunter is out there looking for his moose to fill his freezer, maybe he tells himself he better aim straight.”

Palin had a harder time explaining what, if any, financial harm she suffered from the Times’ editorial. “My relationship with Fox News, whom I was working for, after that incident and me wanting to defend truth, the relationship was never the same, and that led to me not working for them now.” (Despite these claims, Palin acknowledged that her Fox contract ran for more than a year after the Giffords shooting, and that she got a second contract into 2015. “It wasn’t the same relationship, though.”)

It’s impossible to predict what will come of this suit, which is scheduled to go on trial in less than five months. The case was filed in the Southern District of New York, not Anchorage, so the Times will have a local jury. By that time, it will have dragged on for nearly four years, racking up huge legal costs. And Palin, whose star has fallen in conservative circles, is likely to milk the case for every ounce of publicity it can generate.

One factor that jurors would need to consider is the speed and openness with which the Times dealt with its mistake. Says spokeswoman Danielle Rhoades Ha: “Our standards are among the strictest of any news organization, and when we fall short of them, we correct our errors publicly, as we did in this case.”

An adage in newsrooms is that if you want job security, get yourself named as a defendant in a lawsuit. Perhaps that was initially true for Bennet, who held on to his job for three years after mismanaging the editorial, but lost it after Senator Cotton’s piece ran.

It was a sad coda: Over nearly fifteen years, Bennet built an enviable legacy for his ability to hire top-flight writers, engage complex issues with intellectual verve, and adapt to the digital age. That reputation was tarnished more than once at the Times, and it’s hard to imagine it will improve should this case go to trial.

When Bennet left the editorial page in June, his boss, publisher A.G. Sulzberger, noted that the Cotton op-ed represented “a significant breakdown in our editing processes,” and then added, almost gratuitously, that it was “not the first we’ve experienced in recent years.”

Sulzberger didn’t mention Sarah Palin’s lawsuit. He didn’t have to.

Correction: A previous version of this story misidentified the location of the June 2017 shooting in Alexandria as taking place in Arlington. CJR regrets the error.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.