Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Britain’s Official Secrets Act, the country’s main legal instrument against breaches of governmental security, is reviled by journalists on both sides of the Atlantic. It is criticized as an example of state overreach that conceals official wrongdoing and incompetence.

And now the UK government is considering changing it to strengthen its grip and make the punishment for defying it even harsher.

Journalists say the changes considered by the government of Prime Minister Boris Johnson (himself a former journalist, albeit one fired from his first job for fabricating a quote) would remove the distinction between spying for foreign adversaries and leaking for public illumination. It would expose both reporters and the whistle-blowers they rely on to penalties previously reserved for espionage, and criminalize the very best journalism.

The better news is that rethinking the Official Secrets Act has rekindled a debate in Britain that is long overdue here: Should the state punish people who defy secrecy rules for the public interest? If, on balance, what the British call an “unauthorized disclosure” (and we call a leak) yields a broad benefit that outweighs any harm it causes, should the leaker be punished at all? At the very least, shouldn’t the accused be allowed to argue that violating the secrecy classification was in the public interest—and if a court agrees, walk free?

The task of modernizing the Officials Secrets Act (OSA) was first taken up in 2016 by an independent entity called the Law Commission, a think tank that advises Parliament on thorny legal matters. The job was prompted by concerns that the law, last revised in 1989, didn’t address such matters as digital disruption, data theft, and spying conducted from abroad.

Last year the Commission recommended longer sentences for violators than the current two-year maximum (the Johnson regime now seeks a fourteen-year max.) It eliminated the distinction between an original leak and “onward disclosures”—meaning publication by the press. Both would be equally punishable. Worst of all, it wanted to discard the need to prove that leakers meant to do damage. Instead, if they recognized they might cause harm, they could be prosecuted.

But while toughening the law, the Commission tossed a major bone to the press. It proposed that the law be rewritten to include a public interest defense. Whistle-blowers who disclose secret evidence of official wrongs would be able to claim that they did it to serve a wider good.

That wouldn’t mean a free pass for whistle-blowers. Whether the violation was justified would still be a complicated question: Was the leak limited to the minimum needed to expose the wrongdoing? Were there alternatives to public disclosure that might have led to correctives, and did the informant try to use them? Was the informant seeking personal gain? Did the disclosures harm legitimate state interests?

So even with a public interest defense available, a case would still have to be made. And a court would have to make a judgment.

“Everyone accepts that some government information must remain secret,” Oxford law professor Jacob Rowbottam told the Commission. “The system of secrecy, however, requires safeguards to ensure that the power to withhold information is not abused to shield government from criticism or embarrassment, or to cover up wrongdoing.”

A public interest defense already exists in Britain, notably in employment law, where the duty to respect workplace confidences can be overridden to expose illegal or environmentally destructive practices.

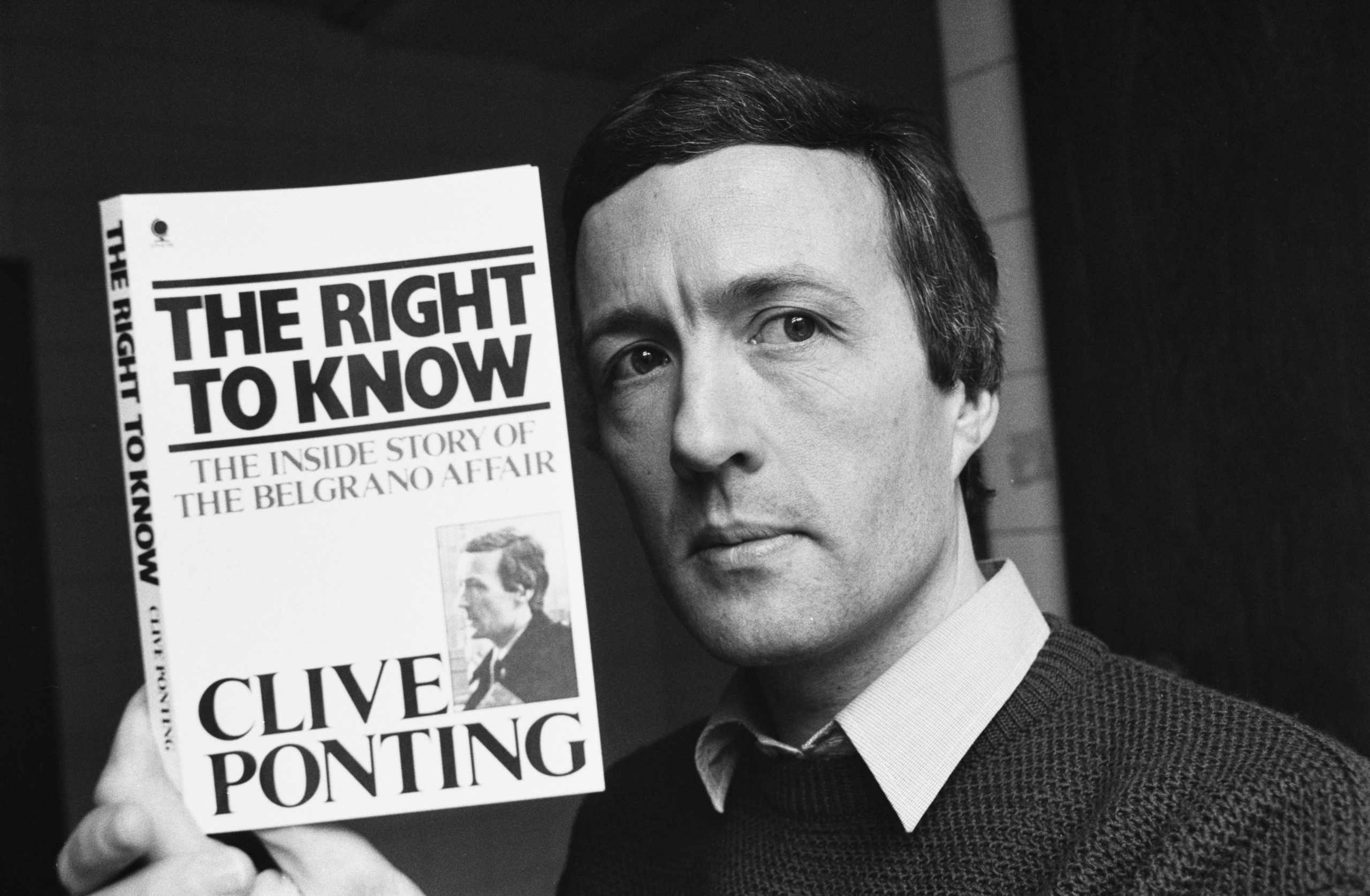

The defense has also, from time to time, barged in through a side door in national security matters. A famous case involved Clive Ponting, a defense official who debunked a Thatcher government cover story that the Royal Navy had sunk an Argentine cruiser during the 1982 Falklands War—at a staggering loss of some 300 sailors—because it threatened British warships. Ponting leaked secret documents that exposed that story as a total lie; he was prosecuted, and jurors, who thought he was a hero, flouted the judge’s instructions and sent him home.

Advocates for writing the public interest defense into the OSA say it would ensure that British law complies with the European Convention on Human Rights, whose Article 10 protects the freedom “to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority…” It would also put the UK on the same footing as Australia, Canada and New Zealand, three of its chief international intelligence-sharing partners in the so-called Five Eyes. That would leave the United States alone among the five in refusing to acknowledge that there are times when secrets can legally be blown.

Sadly, the Boris Johnson government has rejected the Law Commission advice and declined to add the public interest defense from the OSA reforms it is pushing. But the emergence of the defense as a serious proposal for another of our closest allies underscores the authoritarianism of the US approach to secrets. Under our law, official secrecy in the national security realm can never be wrong. It doesn’t matter whether what’s concealed is torture, illegal domestic surveillance, the wiretap of UN diplomats, or the murder of civilians.

Chelsea Manning was sentenced to 37 years without being allowed to even say why she went public with evidence of military and diplomatic criminality. The country’s best news organizations won Pulitzer Prizes for publishing astounding information that, a decade later, Julian Assange is still being sought to stand trial for giving them. Edward Snowden exposed domestic surveillance that was judged illegal and unconstitutional, and if he returns from exile, he will be barred from even pointing that out in his defense.

This must stop. It is time that the regime of secrecy that has darkened and deepened in the decades since 9/11 is forced to give way to the demands of holding government accountable.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.