Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

I got an email the other day from an engineer who wants to build a new website to weed out bias in journalism. His idea made me chuckle—not just because of the technical difficulty of detecting something as subjective as bias, but because it is based on the widespread misconception that bias is bad.

For years, conservative critics have claimed that lefty journalists slant their coverage, and wrongly suggested that bias in journalism is always bad. These attacks eroded the credibility of the mainstream media and fueled the rise of conservative outlets. Three-fourths of people cite bias as a factor in their mistrust of the news media, according to a 2018 Gallup survey for the Knight Foundation’s Trust, Media and Democracy project.

In fact, bias in journalism is good. It just needs to be labeled and understood.

RECENTLY: A deadly year for Mexico’s journalists

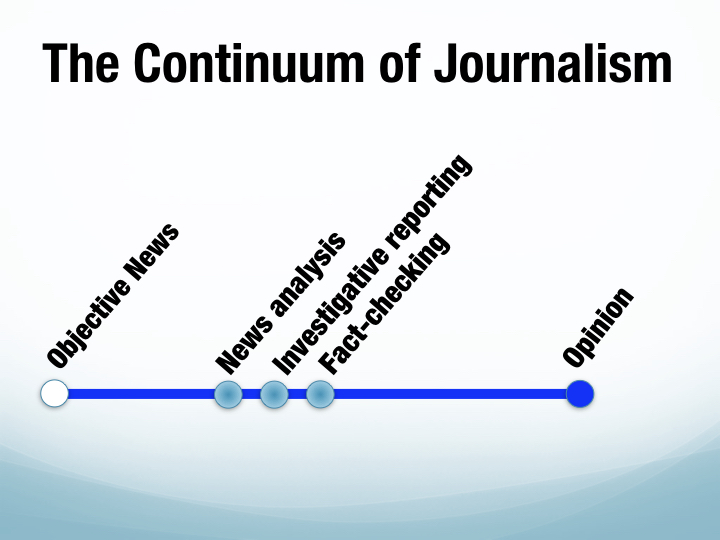

In my courses at Duke, I begin each semester with a diagram I call the “Continuum of Journalism,” which includes a range of journalistic genres: op-eds, investigations, fact-checks, you name it. The continuum could easily be rebranded “The Bias Meter.” At one end is what I’ve labeled “Objective News”—stories that strive to present all points of view. At the other end is “Opinion,” which includes articles by columnists, op-eds, TV and film reviews, and newspaper editorials. Pieces on the “Opinion” end of the spectrum help us to explore our feelings on issues and sharpen our political views; they soften our perspectives, or crystallize them. We like bias in these types of articles, and know to expect it.

Bill Adair’s “Continuum of Journalism”

Between those two poles is a broad range of journalism. There are analysis articles, fact-checks, and other types of reporting that lack some traditional aspects of objectivity, but don’t advocate the way an opinion column might. With the exception of the most balanced news stories, most of these genres, and the stories they shape, contain some bias and fall somewhere in the middle.

An investigative story, for instance, proceeds from the bias that a politician should not have a conflict of interest—a principle most people might agree with, but a bias nonetheless. A fact-check is based on objective reporting propelled by the conviction that it’s wrong for politicians to lie.

Readers seem particularly confused about articles in the middle. They don’t know journalism terminology, and may not understand a label such as “News Analysis.” News organizations deserve some blame for that because, historically, they have done a poor job of explaining and differentiating between types of journalism.

Newspaper readers traditionally got cues from the location of articles. Opinion columns were on the editorial or op-ed pages; local columnists were on the front of the metro section. When readers picked up a magazine such as The Atlantic or National Journal, most understood they were getting something different than they got from their newspaper. The magazine had a distinctive point of view—and, therefore, some bias.

Now, for many readers, online publishing amounts to a journalistic stew with ingredients they can’t be sure of. A Facebook link can transport you to a story at an unfamiliar publication whose biases are unknown or not clearly labeled.

The problem is magnified when readers’ lack of understanding about journalism’s genre bias collides with their partisan bias.

Imagine you’ve never read The Atlantic before and then randomly encounter this article, which makes the strong point that an “unconventional” presidential candidate might buy his way into the debates. Where does it fall on the Continuum of Journalism? There are clues in the writing and the headline that it’s got some partisan bias; genre-wise, its only label is “POLITICS,” which preserves the possibility that readers will receive it as “objective news.”

Try the same for this National Review article, which makes an even stronger point about money in politics—that Joe Biden is ethically compromised because he got big bucks for speeches and is now running for president. It’s more of an opinion column than an analysis. But readers are left to discern that from the headline (“Joe Biden Gets Paid—a Lot”) and the label (“ELECTIONS”).

Cable news channels offer their own stew of news and opinion. As Mark Stencel and Eric MacDicken wrote in CJR last year, news anchors and opinion-driven hosts are presented to viewers with little if any distinction, and partisan commentators and “analysts” are not always clearly identified. Viewers understandably get confused about who has a bias and who doesn’t. Stencel and MacDicken recommended networks adopt fuller on-screen “nutritional labels” that would provide details about each commentator’s background and affiliations.

Media executives want to believe that readers and viewers understand the nuances of journalism and can navigate the space between “objective” news and obvious opinion. But they don’t. Many readers need guidance.

Some news outlets have tried to address the challenge using labels and definitions developed by the Trust Project, an effort started at Santa Clara University to improve the credibility of journalism. The Washington Post was an early adopter, using recommended labels such as “analysis” and “review”. But the progress at other publications is uneven, and too many people remain stuck somewhere along the Continuum of Journalism, unsure of where they are and looking in vain for a sign.

ICYMI: Between immigration authorities and the people they target

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.