Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

A new report by the Media Development Foundation outlines how local news in Ukraine has operated since Russia invaded on February 24, 2022. Unsurprisingly the study, which surveyed thirty-nine regional, independent news publishers, shows a radical transformation in many operations, but also the enormous resiliency of the local press.

MDF, a media expertise hub headquartered in Kyiv, has for years published annual reports on the state of local media in Ukraine. The idea to conduct a special wartime edition was led by Andrey Boborykin, executive director of Ukrayinska Pravda, one of Ukraine’s largest independent news organizations. After Boborykin and some colleagues relocated to western Ukraine, they noticed that many media managers seeking help through their Ukrainian Local News Emergency Fund were responding in vastly different ways.

“Everything has been disrupted by war,” says Boborykin. “Some publishers were quite well prepared for that and were responding to this challenge in a very rational and effective way, and some were totally, by all means, not.” They hoped this report would provide a clearer picture of the local media landscape during wartime and provide recommendations.

Ukrainian media are now almost entirely reliant on emergency grant funding to stay afloat as local advertising has all but disappeared. According to MDF, around 81 percent of local newsrooms applied for international aid in the two months after the invasion began. This includes applications to international donors; government funds, like the US Agency for International Development (usaid), which committed $131 million in aid to Ukraine; and fundraisers from individual donors organized by groups like MDF and the Lviv Media Forum. (The Tow Center previously wrote about a GoFundMe campaign in support of local Ukraine media that has so far raised more than 940,300 euros.)

Notably, though, around 19 percent of newsrooms haven’t applied for grants at all. Tanya Gordiienko, a Ph.D. student of media and communications at the Mohyla School of Journalism and a lead editor of the report, says this largely comes from a lack of confidence about whether big donors would want to support smaller, regional newsrooms in Ukraine. “This is something that I think we should take into account and work on—explaining to regional media that they are an important part of the ecosystem and their voices should be heard,” explained Gordiienko.

Available funds were by far the largest concern among those surveyed, with 69 percent of respondents noting this challenge. While around a quarter of regional newsrooms reported having enough funds in their coffers to budget on a monthly basis, a few outlets are operating on such thin margins that only a week or two of funds remain. A small number of employers have been unable to pay salaries, and a share of media professionals now work on a “voluntary basis.”

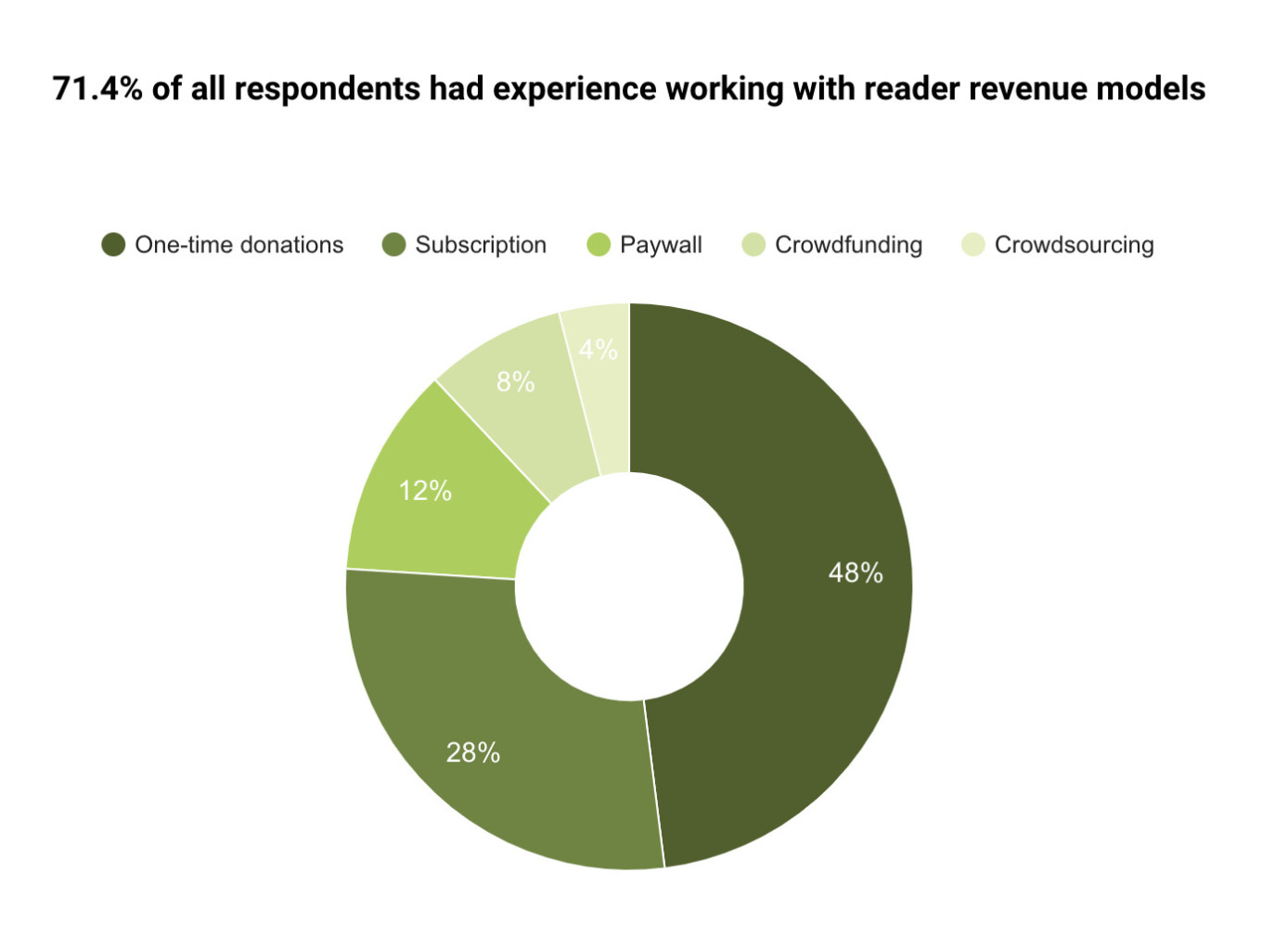

In the years preceding the invasion, independent media in Ukraine struggled to monetize their products and transform their organizations into sustainable businesses—issues similar to what local newsrooms face globally, including those in the US. Boborykin says that reader revenue in Ukraine is “almost nonexistent” and many local outlets are struggling to implement an effective digital strategy.

Only three quarters of the 35 local Ukrainian newsrooms MDF surveyed last fall have experimented with various reader revenue models.

He also pointed to the disruption of the local advertising markets by the tech platforms, namely Meta (formerly Facebook) and Google, which continue to exert a stranglehold on digital advertising and online news distribution worldwide. “The [local Ukrainian] media don’t have the resources to appropriately launch native advertising or any other sorts of direct monetization,” says Boborykin. And the platforms, which are now among the largest funders of news globally, have done relatively little to directly fund newsrooms in Ukraine both prior to and amid the Russian invasion.

While Google’s and Meta’s respective journalism initiatives have provided some direct support to Ukrainian news organizations in the past, it’s been scant. Meta so far has partnered with nine different organizations in Ukraine for its third-party fact-checking efforts, and a Meta spokesperson told Tow that in response to the war, they’ve expanded this capacity across the region. The Google News Initiative also launched a “Hands-on Machine Learning” course in partnership with the data-journalism-focused Ukrainian publication Texty in December 2020.

However, neither the MJP nor the GNI has launched expansive programs specific to Eastern Europe, like recent investments across Latin America. Ukrainian media were also noticeably absent from the list of countries that received funding from the GNI’s covid-19 Journalism Emergency Relief Fund (JERF), one of its most expansive global initiatives to date, which boasted $39.5 million offered to more than 5,600 newsrooms across 115 countries for general spending. While the MJP, in tandem with the European Journalism Center, launched a covid-19 emergency fund that funneled money to 28 countries across Europe in 2020, only 3 Ukrainian newsrooms were chosen out of 162 total news organizations, and no freelance journalists were selected.

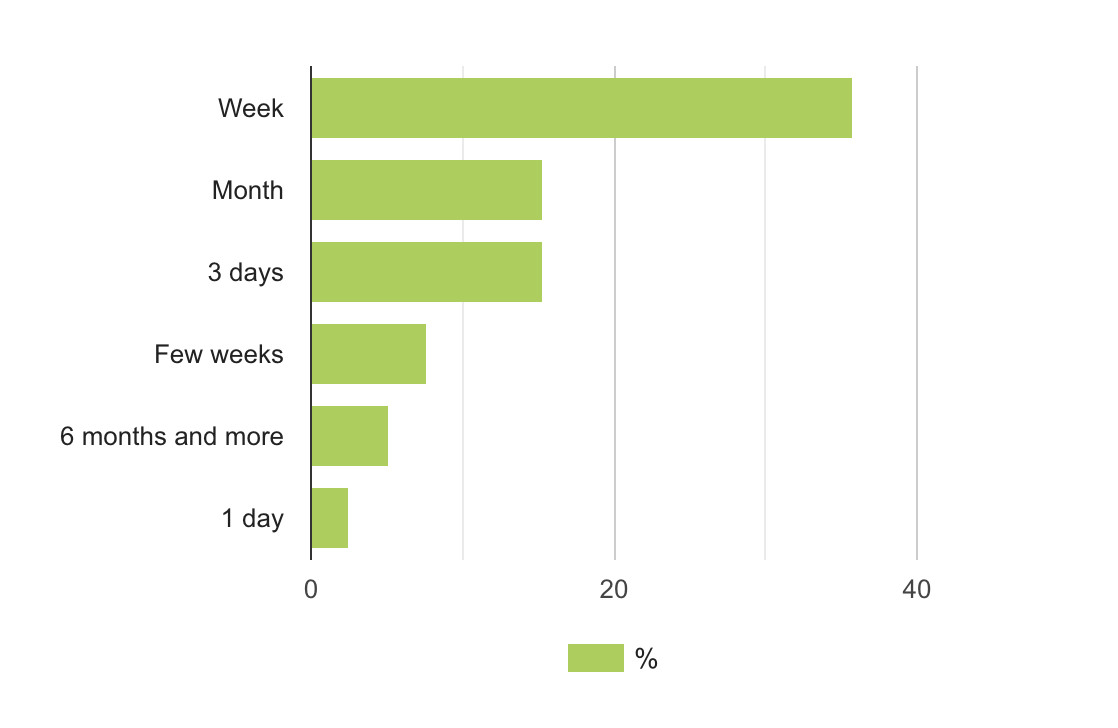

A Google spokesperson told Tow in an email that, “for many years, [Google has] worked with journalists and news organizations in Ukraine and Central and Eastern Europe to support them as they adapt to the changes the internet has brought,” which includes “products that drive traffic to their sites, [Google] ad products they can use to make money online, and training and innovation programs.” While Google did outline for Tow the ways its programs have supported some Ukrainian journalists over the past seven years, it has not provided direct cash funding to assist publishers in Ukraine like it did for newsrooms in other countries during the covid-19 crisis. And the European Innovation Challenge that Google launched last week, which Ukrainian publishers can apply for, may present significant challenges for newsrooms that wish to do so, as MDF found that 38 percent of respondents indicated an inability to plan ahead amid the war—a necessity for drawing up plans to innovate in the industry.

A graph from MDF’s 2022 report breaks down the percentage of Ukrainian newsrooms with the capacity to plan ahead by their reported time frame.

Meta similarly has not provided direct emergency relief funding to Ukrainian media during this period of crisis. A spokesperson for the tech company pointed Tow via email to Meta’s third-party fact-checking initiatives and some product work it has done since the onset of the war to connect people in Ukraine with timely information and resources.

Boborykin believes this patchwork of projects is a start, but “by far not enough.” He’s especially frustrated that the tech giants’ lack of support comes amid disinformation campaigns on widely used platforms in Ukraine, such as Facebook and YouTube, that he believes are comparable to those in Myanmar or China. (Both campaigns used Facebook to promote genocide, of the Rohingya and Uighur populations, respectively.) Boborykin also recently spoke with Coda Story on Meta enforcing “one size fits all” policies—intended to curb Russian propaganda—that are now restricting independent Ukrainian media from publishing vital, sometimes graphic content under the same rules. (The Tow Center has created a comprehensive list since the onset of the war on actions taken globally by platforms, publishers, and governments affecting the information ecosystem in Russia and Ukraine.)

This unrestricted, readily available cash funding is sometimes the most urgent need but is currently missing from the crisis response of many philanthropic, corporate, and government funders. James Deane, cofounder of and consultant to the International Fund for Public Interest Media, told Tow in an email that the destruction of Ukraine’s business model for journalism “highlights in especially stark detail that the most immediate challenge for public interest media is how to mobilize, allocate and disburse funding so that it reaches the bank accounts of media institutions who need it.”

According to Deane, media support thus far has focused primarily on editorial and business development—trainings, mentoring, tool kits, and more—with the transfer of money both secondary to and contingent on strategies like sustainability. He added that “the volume of money available to support independent media around the world is woefully insufficient.” (The IFPIM recently announced a call for funding across seventeen countries, including Ukraine, and hopes to raise a billion dollars for global media support.)

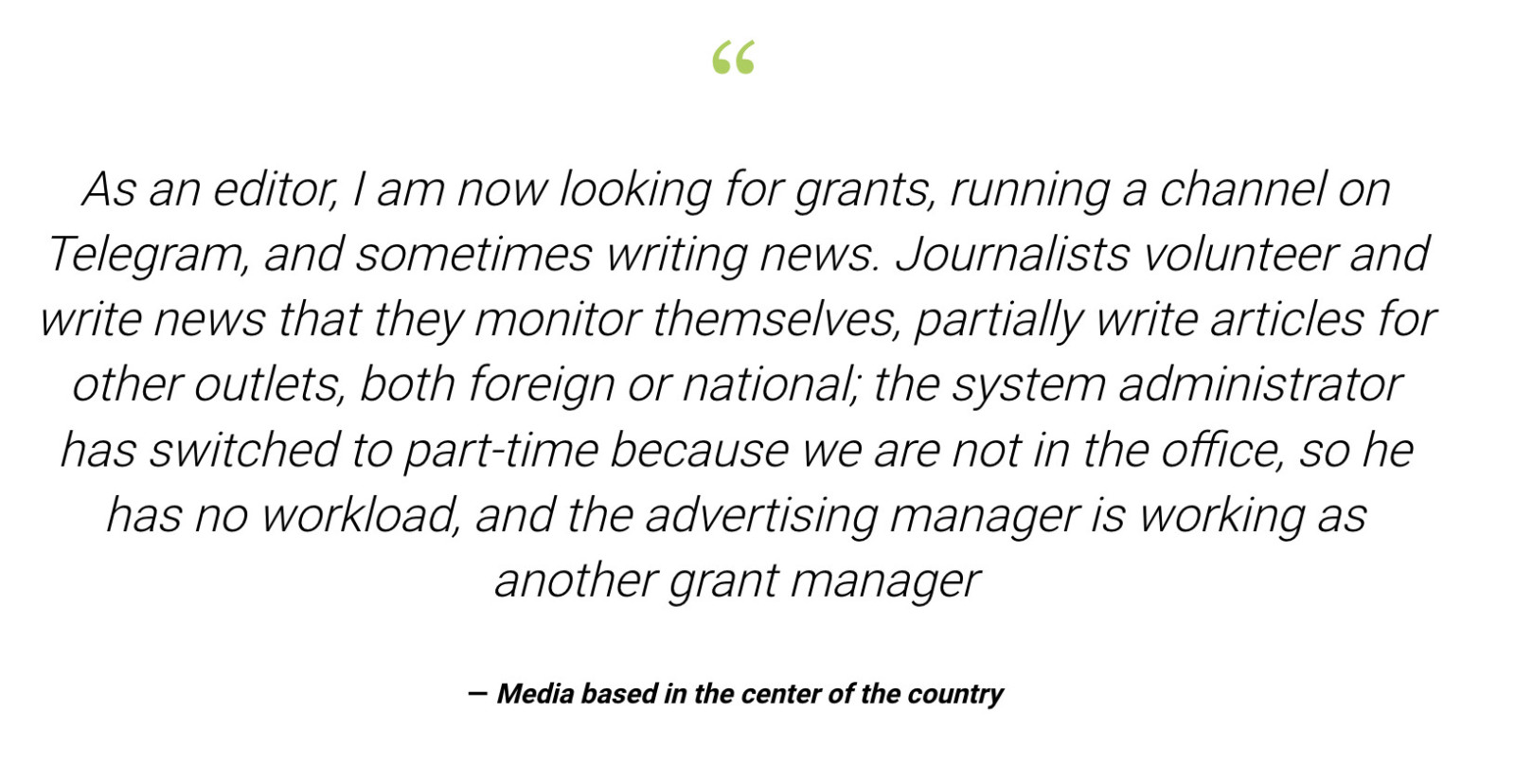

MDF additionally found that the war has taken an “extreme” psychological and emotional toll on staff—around 61 percent reported experiencing as much—stemming not only from exhaustion and fears for safety but also from increased responsibilities in roles not related to their qualifications. According to the report, relocations have exacerbated emotional breakdowns and conflicts, frequent air raids have triggered anxiety and disrupted sleep, and productivity has suffered for nearly half the newsrooms surveyed.

A survey respondent in central Ukraine told MDF what the significant increase in their work responsibilities has involved.

One of the most hopeful findings to come out of the MDF report, though, is the number of respondents with strategic post-victory plans—a little more than 61 percent—who hope to report on liberated cities and launch new storytelling formats as a way to revitalize their communities.

In the meantime, keeping the independent Ukrainian press operational is what some are hoping will help Ukraine both survive the war and continue functioning as a democratic society. Gordiienko says that regional media “may seem to be a bit old-fashioned, not so fancy as the bigger media with more resources,” but Ukrainians are relying on local news to evaluate life-threatening concerns in real time, like whether to seek shelter or leave a city altogether. “Yeah, regional media have a lot of issues, but we cannot abandon them; we need to support them, to help them develop and keep their communities informed.”

You can read the full wartime edition of the state of regional, independent news in Ukraine here.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.