Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

The story starts with a text message. Late one night this past February, veteran reporter R.G. Dunlop received a cryptic message from a longtime trusted source. It said something like, “Do you know about Rep. Dan Johnson’s past? I hate hypocrites,” Dunlop says. At the time, he didn’t know much about Danny Ray Johnson, the Kentucky state representative in question. Dunlop, along with reporter and producer Jacob Ryan, started looking into that initial tip.

As the months passed, new leads emerged—and the story became bigger than Dunlop ever expected. “We didn’t know what we had,” he says.

RELATED: Suicide by news subjects shouldn’t be pinned on media, experts say

What started as a late-night text eventually turned into a seven-month, five-part investigation into the preacher-turned-politician. The resulting podcast, The Pope’s Long Con, is a herculean effort from the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting and Louisville Public Media. It launched on December 11, and two days later, the investigation’s subject, Johnson, died by suicide. He drove to a bridge outside Mount Washington, Kentucky, and shot himself with a .40-caliber handgun, according to Bullitt County Sheriff Donnie Tinnell. It was a tragic and unexpected outcome following the release of KyCIR’s investigation. Yet the team handled the aftermath with the same sensitivity, professionalism, and commitment to truth that defined The Pope’s Long Con.

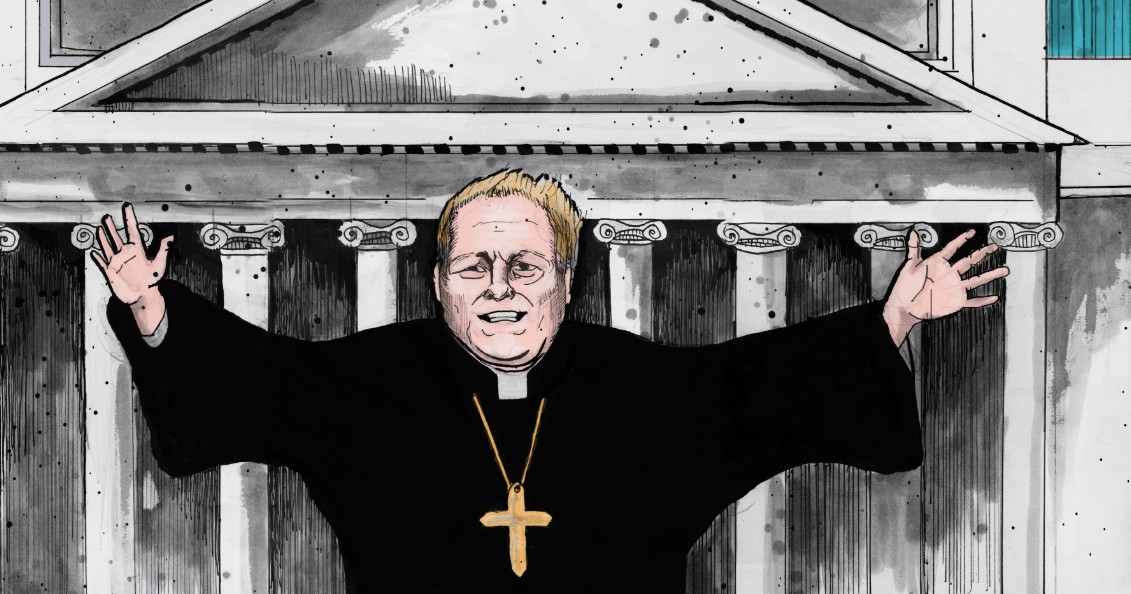

Illustration by Carrie Neumayer for KyCIR

Louisville Public Media created KyCIR, its nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom, almost four years ago to expose wrongdoing in the public and private sectors and to hold leaders accountable. The Pope’s Long Con does both. For seven months, Dunlop and Ryan tracked how Johnson, who called himself “Pope,” was able to cultivate a public persona built on lies and deceit. Johnson’s past was riddled with unexamined controversy, including attempted arson, false testimony, and an alleged molestation. “We wanted to find out: why did he do this? And how did he pull it off?,” says Brendan McCarthy, KyCIR’s managing editor.

ICYMI: The New York Times begins 2018 on a sour note

A former bishop of an evangelical church, Johnson was elected to the Kentucky legislature in 2016. His campaign was not without controversy; he made national headlines after posting racist images of President Barack Obama and his family on Facebook. That incident, and everything from his past, went largely unchecked by state and local media organizations, including KyCIR, during his campaign. (The media’s shortcomings ultimately became part of the podcast’s final episode, “When Our Institutions Fail.”)

Nobody took the bait then, but KyCIR eventually did. The Pope’s Long Con is its biggest investigation to-date. Usually the team’s investigations result in a 3,000-word web story and a five-to-six minute radio piece. This one culminated in a more than 10,000-word web story and five-part podcast. “We knew fairly quickly that it would be more complex than we initially envisioned,” Dunlop says.

ICYMI: The most recent Trump bombshell, and a stunning revelation about Melania

Dunlop’s initial source told him about a mysterious attempted arson plot involving Johnson from 32 years ago. He employed basic shoe-leather reporting to find the right records and documentation. When he couldn’t find them in the local court archives, he turned to the federal court system, which led to the discovery of additional records, including one about Johnson’s possible involvement in a church fire in 2000. He talked to arson investigators and the police personnel involved in those cases. The more he dug, the more he found. The church fire investigation led him to sources who hinted at impropriety in the church, including an alleged sexual assault. Dunlop asked the Louisville Metro Police Department for records and came across a heavily sanitized report involving a sexual assault allegation. The accuser’s name wasn’t on it, and the details were minimal, but it was enough to spur Dunlop to find out more. (The accuser, Maranda Richmond, was 17 at the time of the alleged assault, and while she did go to the police, they ultimately closed her case with no resolution or charges. When Johnson hit the campaign trail in 2016, Richmond reached out to people in media and politics about her story, but the concerns didn’t gain traction, according to KyCIR.)

R.G. Dunlop sits down with the woman who alleged sexual assault. Photo: J. Tyler Franklin/KyCIR.

At the same time, Dunlop, with the help of KyCIR colleagues, excavated the material for the five episodes from more than 100 interviews and 1,000 pages of public documents. “It was one of those ‘don’t leave any stone unturned’ situations, and we tried to turn them all over,” Dunlop says. They followed leads and tracked down sources in Texas, California, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Louisiana. They obtained documents from the Louisville arson investigators, the Kentucky Legislative Research Commission, and the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, and leveraged public court filings, sworn statements, campaign finance reports, copies of bank statements, and licensing records. They culled archives, pored over Johnson’s sermons and campaign videos, and consulted expert sources.

And, in an effort to proactively combat any accusations of “fake news,” the KyCIR team posted many of these findings online for the public. “There is such distrust of the media,” McCarthy says. “Showing our work and sharing the resources [was important] to engender trust with our audience.”

For a long time, KyCIR thought they’d get an interview with Johnson himself. He declined many requests, cancelling meetings and invoking “fake news” in phone calls with the team. But despite Johnson’s unwillingness to cooperate, KyCIR eventually had a story which was “ironclad” in Dunlop’s words.

When the podcast launched, the response was immediate. KyCIR broke all their web traffic records in the first day, and its audience overwhelmingly lauded the investigation. Republican and Democratic statewide leadership asked Johnson to step down from public office, and the Louisville Metro Police reopened the investigation into the alleged sexual assault, though Johnson publicly denied all the accusations uncovered in The Pope’s Long Con.

ICYMI: 11 images that show how the Trump administration is failing at photography

And then the unexpected happened. Two days after the podcast’s launch, when three episodes had aired on the radio, Johnson shot himself. “To be honest, we’re still wrestling with this,” McCarthy says. “It’s any journalist’s nightmare to have someone you reported on commit suicide in the wake of a report. It’s something here nobody had envisioned.” Dunlop was at home when he found out and immediately checked in on the woman who accused Johnson of sexual assault: “I suspected this would be very difficult for her, which in fact it was.”

There’s no playbook for journalists about how to handle situations like this, he says: “You don’t turn to page 13 and figure out how to deal with this.” Lots of hugging and the unwavering support of colleagues, friends, and listeners helped as the KyCIR team grappled with the tragedy. They kept hearing from same message from people: We need you. The reporting may have factored into Johnson’s death, but Dunlop supports the work accomplished by the KyCIR team. “No one has challenged any aspect of the story,” Dunlop says. “It’s not as though a story that was erroneous brought this man down. We revealed his life history, and it obviously didn’t resonate well with him. While in my head I understand I didn’t kill Mr. Johnson, he pulled the trigger, it feels very difficult to get over the emotional part of this.” Louisville Public Media also made counselors available to its staff following the news of Johnson’s suicide.

KyCIR also modified the roll-out of its investigation following Johnson’s death. Initially, the plan was to air all five episodes on the radio, but they chose not to air the last two “out of respect for victims of trauma in the immediate wake of Johnson’s suicide,” according to a statement from Stephen George, executive editor of Louisville Public Media. Instead they immediately released all five episodes online for those who wanted to hear the stories. KyCIR followed up their investigation with coverage of Johnson’s suicide, though Dunlop and Ryan were not involved in the reporting, and plans to produce a final chapter of The Pope’s Long Con in the coming weeks.

Unsurprisingly, The Pope’s Long Con became part of the story after Johnson’s suicide, with some directing the blame on KyCIR’s reporting. Johnson’s widow, Rebecca Johnson, pushed this narrative on The Today Show: “I am confident if that little greasy reporter had not done what he did, my husband would be alive right now.” (She did acknowledge other factors in interviews with her local broadcast news station WHAS.) And The Washington Post, in both an opinion piece and reported story, lumped Johnson’s suicide in with the #MeToo movement. Kathleen Parker, a WashPo opinion writer, used Johnson as a peg for what she’s calling a “rush to judgment” in the recent wave of sexual harassment accusations: “Johnson’s suicide reminds us that the best of causes conducted without the usual rules of law can lead to disastrous, even fatal, consequences.” It was a poorly received piece—based on a quick read of its reader comments—and an insensitive one, incorrectly writing that the accuser remained anonymous (she spoke with KyCIR on the record). Another WashPo news story also all but ignored KyCIR’s reporting in writing about Johnson’s career and death.

This ensuing media coverage frustrated the KyCIR team for two reasons. First, there was minimal pushback from reporters against claims like the ones made by Johnson’s widow. “I wish there had been a more questioning attitude by reporters after Mr. Johnson died, and less an unquestioning acceptance of what were people were saying about us and our work, and whether or not they accurately or inaccurately represented our work,” Dunlop explains. Second, the media incorrectly identified The Pope’s Long Con as belonging to the #MeToo movement. The sexual assault allegation was just one episode of the five-part series, Dunlop says, and while important, it’s not the full story: “It’s one part of a multifaceted, complicated life. Some of the accounts overlooked the other facets of his life.”

The Pope’s Long Con is an exemplar not only of dogged local reporting, but also a how-to for newsrooms grappling with unexpected ramifications. For KyCIR, the results of their investigations usually mean a change in law or policy, sometimes a resignation from public office. But never before has it meant reconciling with the death of a subject. “We wanted justice to be done, but nobody wanted him dead,” Dunlop says.

ICYMI: TV stations fight ‘sea of sameness’ with experimental local news

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.