Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

“This may puzzle you,” Warren Buffett wrote in his annual letter to stockholders in 2012, after buying 28 newspapers. It was more than puzzling. A headline in The Washington Post summed up the reaction from Wall Street and the journalism world: “Warren Buffett buys newspapers. Is he nuts?”

Buffett must have seen the distress. “Advertising and profits of the newspaper industry overall are certain to decline,” he said in the same letter. But he thought the price he paid for the papers—$344 million—was a bargain when measured against the overall quality of the merchandise. Though the internet had consumed help-wanted ads, real estate listings, baseball box scores, stock quotes, and even the comics, Buffett still thought newspapers would survive, and maybe even thrive: “Newspapers continue to reign supreme in the delivery of local news,” he wrote to his investors.

“A reader’s eyes may glaze over after they take in a couple of paragraphs about Canadian tariffs or political developments in Pakistan,” he continued. But that wasn’t true for news about the mayor, crime, property taxes, the high school football team, the water department, the school board—everything that made him a newspaper junkie growing up in small-town Nebraska and reading the Omaha World-Herald every morning at breakfast. At some point, Buffett believed, a new business model would emerge. “Whatever works best—and the answer is not yet clear—will be copied widely,” he wrote.

Image: Henryk Sadura/Shutterstock.com

While he waited for that to happen, Buffett promised not to follow other newspaper owners in cutting costs to save money. There was no sense in selling lemonade made with fewer lemons. “Skimpy news coverage will almost certainly lead to skimpy readership,” he wrote. “Our goal is to keep our papers loaded with content of interest to our readers and to be paid appropriately by those who find us useful, whether the product they view is in their hands or on the internet.” Buffett’s words bounced around newsroom inboxes as a ray of hope. Metro editors and reporters prayed he was right—and that their publishers would take notice. As newspapers hurried to churn out viral Web content to generate pageviews, here was one of the richest men in the world championing the most basic function of newspapers: the five Ws of local news.

RELATED: Print is dead. Long live print.

Turns out, maybe Buffett was actually a little nuts. Four years after his optimistic—and, in hindsight, maybe naive—letter extolling the virtues and economic promise of local news, he has turned bearish on the industry. “Local newspapers continue to decline at a very significant rate,” he told Politico last year. “And even with the economy improving, circulation goes down, advertising goes down, and it goes down in prosperous cities, it goes down in areas that are having urban troubles, it goes down in small towns—that’s what amazes me. . . . Newspapers are going to go downhill.”

So where did Buffett—and newspapers—go wrong? Maybe the economics really are impossible to overcome. Maybe he overvalued the appeal of local news. Maybe publishers, nearly two decades after overlooking and then mismanaging the disruption of digital, are now mismanaging digital at a more micro level, chasing viral news for short-term gains (clicks) while ignoring the long-term consequences (survival). Maybe it’s all three. Whatever the case, it’s now as clear as 56-point type that newspapers are responding to the continued upheaval by shattering the very foundation of what news and newspapering have meant since the days of the penny press.

There was a time when there was no local news. News traveled by word of mouth in small towns, so country newspapers printed whatever news came from abroad by post. Newspapers in larger cities were typically controlled by political parties or commercial elites, printing partisan opinion columns or the comings and goings of ships. Columbia University journalism historian Michael Schudson, in his book Discovering the News, wrote that the business plans of newspapers were often expressed in their names—The Boston Daily Advertiser, The Federal Republican, and the Baltimore Telegraph. They were sold by subscription for six cents an issue.

Around 1830, newspapers began appearing with the words “herald” and “sun” in their banners. Sold on the street for a penny, the papers broke not just from the subscription model but also from selling partisan or commercial dribble. Instead, they sold news—crime, politics, human interest—and used their large audiences as bait to entice advertisers to buy daily spots in the paper. As printing technology, education, and small businesses evolved, so did competition, with many cities supporting more than a dozen daily newspapers. To compete for news, editors set up the beat system as it is known today, scattering reporters at various places where news of interest was made—police stations, courts, churches, government offices.

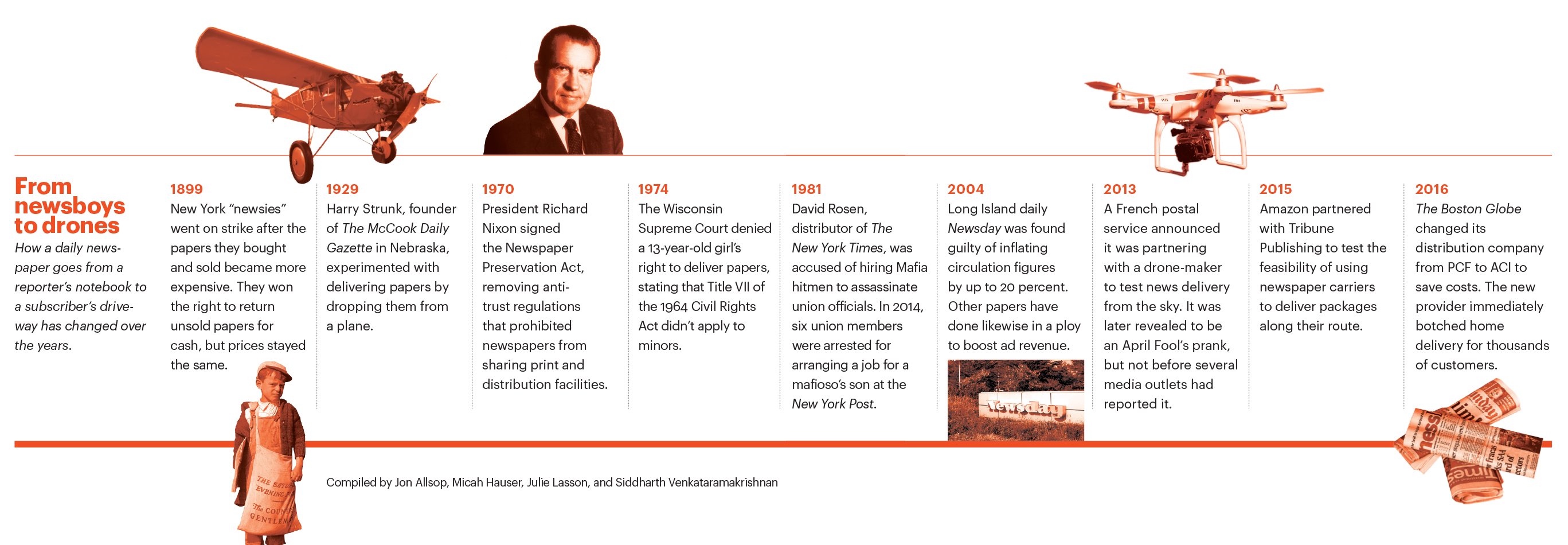

Click on the graphic below to read about how newspaper delivery has changed over the years.

The strategy worked well for about 170 years.

Now, around the country, newspapers small and large are adjusting to the settled economics of the internet—Web traffic drives ad revenue—to fundamentally alter how local news is covered. At The Boston Globe (where I once worked), Editor Brian McGrory sent a lengthy memo to his staff earlier this year describing how the Globe needs to “jettison any sense of being the paper of record.” New idea: “We are the organization of interest.” The Dallas Morning News swapped beats for “obsessions,” the word that online startup Quartz uses to describe its approach to covering the world. The Washington Post (where I currently work), The New York Times, and other metro papers have instructed local reporters to chase “themes” and “ideas,” while at the same time closing bureaus where their readers are—the suburbs.

Organization of interest. Obsessions. Themes. What does that mean in the newsroom? “We will reimagine our beats,” McGrory said in his memo, “toward becoming relentlessly interesting.” In other words, doing away with the fundamental beat system, which McGrory noted hadn’t been refreshed in decades. At the Morning News, reporters are assigned to topics (breaking news, government, etc.), then pick an “obsession” within those topics, reporting on them broadly. At the Globe, Morning News, and other newspapers reorganizing local news coverage this way, the metaphor that comes up again and again is to “think like a foreign correspondent”—meaning don’t cover the day-to-day piffle, but focus on colorful, explanatory enterprise.

Not surprisingly, the driver of this strategy is Web traffic. In the print-centric days, editors had no idea how many people read a story about the local school board appointing a commission to study the quality of cafeteria food. Now, with Chartbeat and other tools, editors can see exactly how many people click on those stories and how they are shared on social media, which is rapidly replacing paper as a platform for news. Not surprisingly, the numbers aren’t large. Editors have interpreted that to mean those stories are, as McGrory put it, “an obligation” that readers no longer feel obliged to read. The Morning News’s editors put it more bluntly: “Getting something ‘on the record’ is not a justification for writing boring stories that no one reads.”

ICYMI: A hidden message in memo justifying Comey’s firing

Were run-of-the-mill beat stories always a waste of time and money? That seems unlikely, given how newspapers essentially printed money for their owners for decades. Or has the internet, with its endless quantity and variety of content, devalued and even suppressed that coverage entirely? That would seem, on the surface, to be a plausible explanation. Clicks are essentially an up-or-down vote on the value of a given story. If people aren’t clicking, they aren’t interested, right?

Not exactly.

Several recent academic studies of online news consumers have taken a deeper, ethnographic approach to understanding reader behavior. Their findings show that counting story clicks is a misguided way to determine reader preferences. “People engage in online user practices that do not necessitate clicks but do express interest in news, such as ‘checking’, ‘monitoring’, ‘scanning,’ and ‘snacking,’ ” according to one study. This behavior is seen clearly when clicks are compared to the amount of time spent on new sites. In one study, local stories represented 9 percent of story clicks by readers. But measured in time spent, those stories accounted for 20 percent of their time on the site, about the same time readers spend on local news in print. “Our findings thus support the argument” that counting online clicks “does not necessarily correspond to the audience’s actual news interest,” the Swedish researchers wrote. Another study of online readers in the Netherlands illuminated why. “A frequent occurrence was that the participants showed interest in the news itself but the headline was informationally complete and consequently, they did not expect to be better informed by clicking,” researchers wrote. Scanning, snacking, monitoring—there is value to local news beyond clicks.

When they aren’t making staffing moves that signal a retrenchment from their communities, they physically retrench, moving newsrooms away from the centers of cities or towns.

There are serious economic and practical implications to thinking otherwise. Local readers, particularly those who read in both formats, are the most engaged users of newspaper print editions and websites—staying longer, consuming more stories, viewing more ads and, in the case of national outlets, subscribing at higher rates. Becoming less essential to loyal customers seems like a bad business idea if the business depends, like most do, on customers coming back. And if reporters no longer show up regularly to meetings, crime scenes, and other places where news is made, how can they build relationships with sources that inevitably lead not just to those broadly written enterprise stories that editors now covet, but to leaks and other paths to major accountability stories?

Newspapers keep showing they don’t care. When they aren’t making staffing moves that signal a retrenchment from their communities, they physically retrench, moving newsrooms away from the centers of cities or towns. It’s certainly true that publishers can no longer occupy property that is sometimes worth more than the newspaper, but as a local columnist might put it, the optics are really bad. The Cleveland Plain Dealer moved its newsroom to an office above a Hard Rock Cafe. The (Philadelphia) Inquirer moved its headquarters—once the biggest building in the city—to an abandoned department store. The Miami Herald’s newsroom was so prominent downtown that people sometimes came to the lobby to kill themselves. The land was sold, the building imploded, and the newsroom was moved out near the airport.

“Just because you don’t see us,” one Herald reporter said after the move, “doesn’t mean we aren’t here.”

By here, he meant 12 miles away.

TRENDING: We tested paywalls at NYTimes, WSJ& WashPo and more. All of them were pretty leaky, except one.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.