Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

If you go to the homepage of the Watershed Post, the online news source for the Catskill region of upstate New York, there are plenty of stories about rural regeneration: agritourism and a new creamery, the ongoing political wrangling over the development of the Belleayre ski resort, property ads where prices are significantly up from a few years ago. But one part of the region’s fortunes is not reviving: the Watershed Post itself.

The first post on the page, and perhaps the last post for the publication, is a long and eloquent letter from the publisher, editor, and founder, Lissa Harris, explaining why the outlet is slowing down:

We have a great local audience that is hungry for news. . . . But I feel the writing is on the wall for digital display advertising, our main revenue stream for supporting online news. I see more and more small businesses taking money they would once have spent with local news outlets, and spending it on digital ads—not on local websites, but on promoted Facebook posts and Google keyword advertising.

As a business person, I can’t argue with that. It works. The titans of the Web have huge and increasing reach, even in our rural communities. They have sophisticated tools for targeting likely customers by geography and demographics. They have products that a business owner can buy for $5 with a few clicks of a mouse, products that require no human time investment on the other end for design or sales or customer support.

The Watershed Post, with 50,000 monthly readers, half within the region and half from outside, is not unusual. Only 15 percent of local news organizations are independently owned and operated, and the pattern of consolidation or closure is rapidly claiming more single-owner or family news businesses. What is unusual is that when the Watershed Post was started in 2010, it represented a version of the future of journalism that was supposed to work: a wholly digital operation built to thrive on the open Web. Harris knew both the region and the communications business in depth. A Catskill native who took up journalism while attending Cornell, she studied science writing as a grad student at MIT and worked for alt-weeklies in Boston before returning to the Catskill town of Margaretville. Her great-great-grandfather John Birdsall founded the Margaretville Telephone Company in 1916, and she felt it was her calling to return home and cover news “for regular people,” as she describes them.

The ambition was to build a hub for news in the economically challenged and politically diverse Catskills. In 2010, flooding in Phoenicia provided the Watershed Post with an early opportunity to see what it could do with live coverage and graphics. A year later, in 2011, Hurricane Irene swept through the region, devastating towns with flooding and mudslides. Harris and her partner were able to keep going, and their live-blogging and resources for help became national focal points for those following the floods. But the reputation and early success of the Watershed Post was never going to scale.

Harris is sad but philosophical about the ultimate inability of her and partner Julia Reischel’s attempts to build the organization beyond themselves. “There was never a point where we could stop wearing all the hats and doing all the work,” says Harris. “The easiest part for us was getting a loyal regular audience. That happened very quickly. But there is a difference between building a business with defined roles rather than being a founder.”

Illustration by Hanna Barczyk

When Reischel resigned as editor last November, Harris thought about hiring a replacement, but realized that the available funds, $30,000 a year, was not what you should be paying an editor running a publication that covers an area the size of Connecticut. The Watershed Post had a list of more than a hundred advertisers, but beginning in 2012, those businesses and others, including the Post itself, started to build their own pages on Facebook. This gravitational pull of advertising dollars away from tiny websites like the Post into Google and Facebook, which allow a high degree of targeting at low cost, make perfect sense for small businesses but spell disaster for local journalism.

Facebook in particular was meant to be part of the solution to the problem of sustaining hyperlocal publishers. The publishing tools and hosting services Facebook offers for free are compelling. But in sparse or poorer areas, they do not allow for the traditional civic bargain of the local press, wherein the businesses and individuals who can afford to advertise, in effect pay for the journalism that covers a community. The decline of local journalism is well-documented, as is the initial optimism that the superior technologies of the Web would eventually allow for better models to be built. But the rise of social platforms has brought with it a requirement of scale both for publishing across multiple platforms and in targeting advertising. The vacuum in local news can also be filled by local businesses or even PR firms that use free tools and social presence to publish.

There was never a point where we could stop wearing all the hats and doing all the work.”

In recent Tow Center research into the relationship between platforms and publishers, we found a common theme, even including quite large newsrooms, such as The Boston Globe: The promise of publishing on the social Web was not enabling better local reporting. The technical requirements needed within small news organizations to make their work compatible with advances such as Facebook Instant Articles and Google AMP are often too much. Just as many local newsrooms complained they were not getting attention from Facebook’s stretched journalism partnership team, Facebook sometimes found it equally difficult to connect with anyone at a small publisher who could tell them how the platform might help their business. New ways to build journalism businesses from scratch undoubtedly exist in a digital environment, particularly in densely populated areas. Digital startups like Billy Penn in Philadelphia and Berkeleyside in Northern California are proof that it can be done, albeit with larger populations in their core demographic. But the recent conversion of Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook founder and CEO, into a journalism evangelist has prompted Facebook to make helping media a focal point of its Journalism Project.

The local problem could be the most challenging of all the rather nebulous issues Facebook has chosen to take on. Unlike fake news and media literacy, fixing a model that allows small outlets like the Watershed Post to become sustainable in the long term means altering the core of the company’s business and increasing the costs of advertising, or finding a mechanism to transfer money to smaller organizations. At a recent Tow Center event in California examining the balance of power between Silicon Valley and journalism, Joaquin Alvarado, the chief executive officer of the nonprofit Center for Investigative Reporting, said that the lack of a viable advertising market to support even state-level reporting in some areas was causing a crisis in journalism and democracy. “If we start by thinking about how to have independent reporting [from] every statehouse, it’s not a trillion-dollar problem,” says Alvarado. “It’s a hundred-million-dollar problem, which in the scheme of things is not that much.” Google and Facebook are predicted to bring in total advertising revenue of over $100 billion this year, which represents about 46 percent of all digital advertising revenue. While both have made efforts to build closer alliances with publishers and declared a strong interest in the health of news and free speech, little has happened to suggest that revenue will be distributed to publishers in a way that will favor the geographically small over the international.

The local problem could be the most challenging of all the rather nebulous issues Facebook has chosen to take on.

The centralizing of costs in large local organizations like McClatchy, Gannett, Tronc, and Digital First Media has to serve shareholders first and communities later, if at all. The copy-and-pasting of local news does not work, as Dylan Smith of Local Independent Online News Publishers told a Google-sponsored Newsgeist conference in Arizona last year. “Giant companies are trying to produce the same templates, but something that might work in Maine will not work in Arizona.” Facebook’s listening tour into regional newsrooms might help reverse the trend of stripping assets from local reporting. Maybe the big talk and hot air expended at global journalism conferences will eventually turn into something more concrete for smaller organizations. Or maybe there will be a civic sea change that miraculously alters the online behavior and spending patterns of the general public. But until then, the green shoots of small local newsrooms remain fragile.

Local goes online

How are local news outlets adapting to digital journalism?

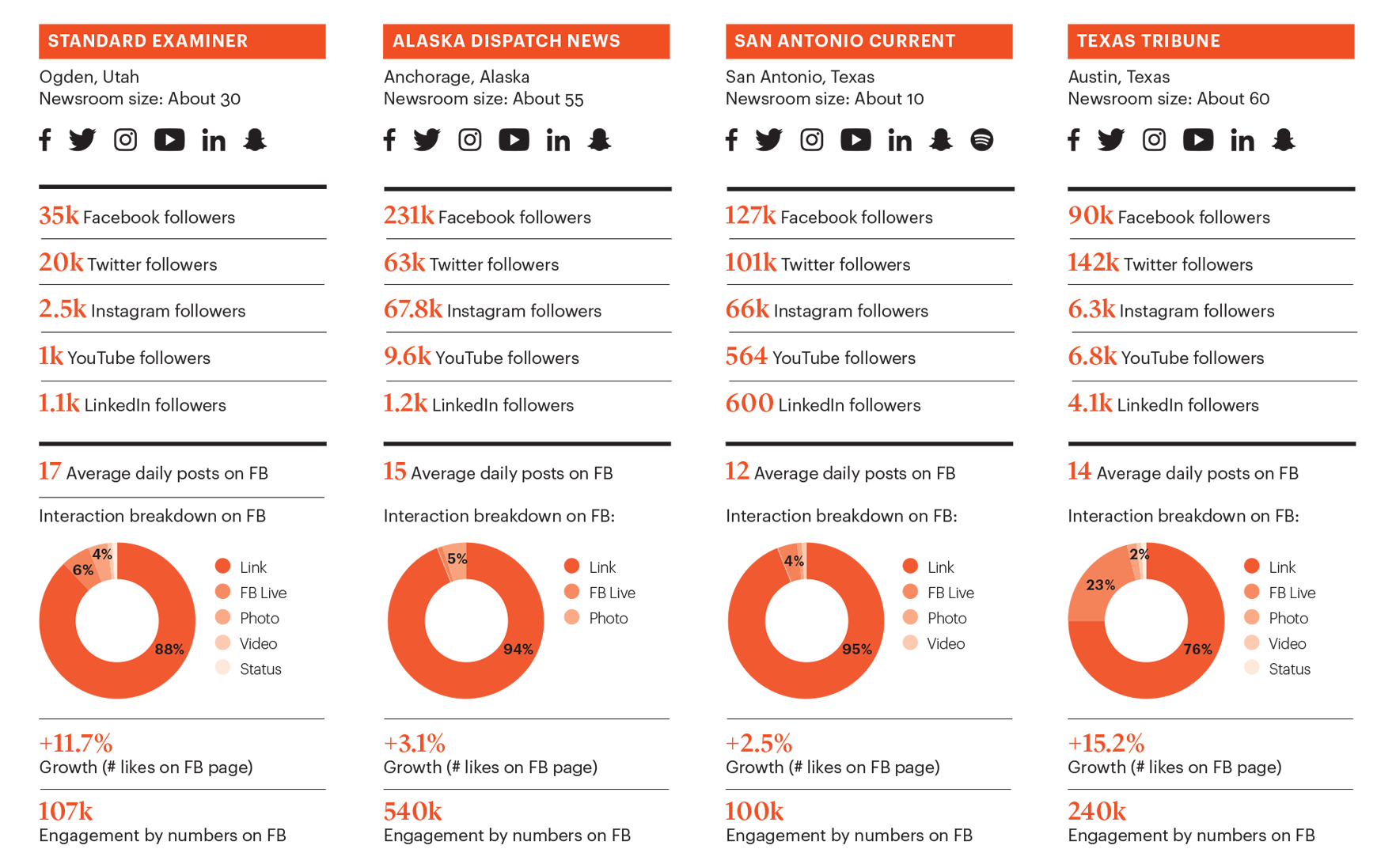

Social media has been seen as both the scourge and the salvation of local newsrooms. We looked at the online presence of four local newsrooms in three states between November 1, 2016, and January 31, 2017.

―Priyanjana Bengani, Danya Hajjaji, and Yassaman Moazami

- Click on the graphic to view at a larger size.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.